Economic Impact Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

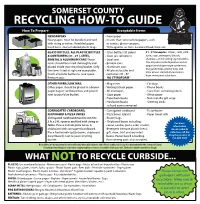

Cardboard and Brown Paper Bags Office Paper, Newspaper, Junk Mail, Magazines, and Catalogs

Recycling Center 801 Diamond Valley Drive Open: Daily to the public during daylight hours This guide will help you properly prepare your recyclable materials for drop-off at the Town of Windsor Recycle Center. This is a drop-off facility. It does not have a buy-back option and is for use by residents and small businesses. Following this information will help maintain the facility and the recycling program for the benefit of the community. IMPORTANT… • Do not leave your recyclables in plastic bags. Plastic bags are NOT recyclable! • The plastic item must be a BOTTLE or JAR. with a #1 or #2 on the bottom. • 99 percent of these will have a screw-on plastic lid (which isn’t recyclable). • Plastic containers with a #3 - #7 on the bottom are NOT acceptable. • Tubs, buckets, deli plates, microwave/fast food trays, wrappers, Styrofoam, toys, patio furniture, etc. are NOT acceptable. • Plastic bottles larger than 2.5 gallons are NOT acceptable. • Syringes and other medical supplies are NOT acceptable. Cardboard and Brown Paper Bags Corrugated cardboard is easy to recognize. It is made of paper and has an arched layer called “fluting” between smooth sheets called “liners”. The drop-off site has two 40-yard hydraulic compactor units for collecting corrugated cardboard and brown paper bags. The compaction system is self-activated by depositing the prepared materials into a six-inch tall slot. Flatten boxes. Cut or tear large boxes into sections no larger than 4 feet by 4 feet to prevent jamming the machine. No wet, waxed-coated or food-contaminated boxes. -

26 the Carton Packaging Fact File CARTONBOARD

26 The Carton Packaging Fact File CARTONBOARD 5 The Carton Packaging Fact File 27 KEY FACTS Cartonboard is a multilayered material. The main types of cartonboard are solid bleached board, solid unbleached board, folding boxboard and white lined chipboard. Cartonboard usually has a white, pigmented coating on one or both surfaces Cartonboard specifications Cartonboard can be vary with respect to the pulp combined with other composition of the various materials to vary the visual layers and by the grammage appearance and to extend (weight per sq. metre in the protective properties grammes) and thickness (microns or 0.001 millimetre) Laminations, coatings and impregnations can be added to extend the range of carton applications 28 The Carton Packaging Fact File CARTONBOARD COMMON ABBREVIATIONS SBB Solid Bleached Board SUB Solid Unbleached Board FBB Folding Box Board WLC White Lined Chipboard Different types and grades the range 200-600g/m 2 for grammage product aroma, flavour and hygiene are of cartonboard and their and 350-800µm for thickness. critical. Examples of cartons where abbreviations. The principles SBB is used are perfumes, cosmetics, of cartonboard manufacture, What are the main characteristics chocolates, pharmaceuticals, frozen developments and treatments of cartonboard? foods and cigarettes. Cartonboard is mechanically strong. What is cartonboard? Its stiffness, rigidity and toughness SBB is sometimes referred to as SBS Cartonboard is a multilayer material provide compression strength to protect or GZ. with, usually, three or more layers, or products in distribution and use. It can plies, of cellulose fibre (pulp) derived be cut, creased, folded and glued, giving What is Solid Unbleached Board? from wood. -

What Notto Recycle Curbside

NEWSPAPERS • Newspaper Newspapers must be bundled and tied • Inserts that come w/newspapers, such with string or twine. Shredded paper as comics, glossy coupons, must be in clear or labeled plastic bags. TV/magazine sections & colored food/store ads GLASS BOTTLES, ALL PLASTIC BOTTLES • Glass bottles (all colors) #1 - #7 Examples: Water, soda, milk, & CONTAINERS (#1 - #7 ), STEEL, • Glass jars (all colors) juice, soap, detergent, bleach, BIMETAL & ALUMINUM CANS These • Steel cans shampoo and cleaning-agent bottles. items should be rinsed thoroughly and • Bimetal cans You may also include peanut butter, placed inside your recycling bucket. Only • Aluminum cans yogurt and diaper-wipe containers, margarine tubs, plastic trays and the items listed at right are acceptable. • All plastic bottles and clear plastic clamshell containers Crush all plastic bottles to save space. containers #1 - #7 from restaurant salad bars. Remove caps. NO STYROFOAM® OTHER PAPER/JUNK MAIL • Magazines • Catalogs Other paper should be placed in a brown • Writing/school paper • Phone books paper bag or cardboard box and placed • All envelopes • Store fliers w/mailing labels next to your blue bucket. • Copy paper • Office paper • Paperback books • Non-metallic gift wrap • Hardcover books • Greeting cards w/hard covers removed CORRUGATED CARDBOARD, • Corrugated cardboard • Tissue boxes CHIPBOARD & PIZZA BOXES • Pizza boxes (clean!) • Paper towel rolls Corrugated cardboard must be cut into • Brown bags 2 ft. x 2 ft. squares and tied with string or • Chipboard boxes including: twine. Please include pizza boxes & cereal, cookie, pasta, cake, cracker, chipboard with corrugated cardboard. detergent (remove plastic liners), Place tied bundle (pizza boxes, chipboard gift, shoe, shirt and any retail & cardboard) next to your recycling boxes. -

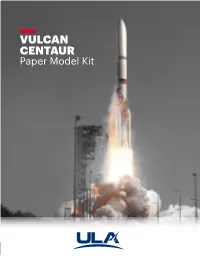

TIP: Remember, If This Is Your First Time Building a Paper Model, It Is Unlikely

BUILDING INSTRUCTIONS Building a model out of paper is really not new. It is, in fact, a lost art that used to be extremely popular before the First World War! If you take your TIP: time, you can make a Museum Quality paper model for display. You Remember, if this is should expect to spend around 2-3 hours. On the other hand, if you just want to spend some time with the kids, get your scissors out and start your first time gluing! Either way, you will have lots of fun! building a paper model, it is unlikely SUPPLIES NEEDED: that you can achieve Sheets of cardstock museum quality. If 9 >60 lb. bond paper (these may sometimes be labelled as cover weight, coverstock, cardstock etc.). you build the model 9 These papers are readily available at office supply stores. 9 These papers should run though your computer printer without one more time, I can issue, however, you should check your printer settings as it may have a 'thick paper type' for better print result. assure you the end Wooden skewers or chopsticks to use as dowel. product will be much One scrap or unneeded CD to use as base. One sturdy ruler. better because of One Craft knife 9 e.g. X-Acto© or equivalent. “Break-away” blade box cutter style your improved paper is preferred (you always should work with a sharp blade). One pair of scissors. model building skills. White PVA glue 9 Always use very sparingly! 9 Always apply glue to paper with a toothpick or unrolled paper clip, never directly from the bottle! Markers 9 Different markers color for edges of your model. -

Articles of Paper Pulp, of Paper Or of Paperboard

Chapter 48 Paper and paperboard; articles of paper pulp, of paper or of paperboard Notes. 1.- For the purposes of this Chapter, except where the context otherwise requires, a reference to “paper” includes references to paperboard (irrespective of thickness or weight per m²). 2.- This Chapter does not cover : (a) Articles of Chapter 30; (b) Stamping foils of heading 32.12; (c) Perfumed papers or papers impregnated or coated with cosmetics (Chapter 33); (d) Paper or cellulose wadding impregnated, coated or covered with soap or detergent (heading 34.01), or with polishes, creams or similar preparations (heading 34.05); (e) Sensitised paper or paperboard of headings 37.01 to 37.04; (f) Paper impregnated with diagnostic or laboratory reagents (heading 38.22); (g) Paper-reinforced stratified sheeting of plastics, or one layer of paper or paperboard coated or covered with a layer of plastics, the latter constituting more than half the total thickness, or articles of such materials, other than wall coverings of heading 48.14 (Chapter 39); (h) Articles of heading 42.02 (for example, travel goods); (ij) Articles of Chapter 46 (manufactures of plaiting material); (k) Paper yarn or textile articles of paper yarn (Section XI); (l) Articles of Chapter 64 or Chapter 65; (m) Abrasive paper or paperboard (heading 68.05) or paper- or paperboard-backed mica (heading 68.14) (paper and paperboard coated with mica powder are, however, to be classified in this Chapter); (n) Metal foil backed with paper or paperboard (generally Section XIV or XV); (o) Articles of heading 92.09; (p) Articles of Chapter 95 (for example, toys, games, sports requisites); or (q) Articles of Chapter 96 (for example, buttons, sanitary towels (pads) and tampons, napkins (diapers) and napkin liners for babies). -

Improved Oil Resistance of Cellulose Packaging Paper By

1 Improved Oil Resistance of Cellulose Packaging Paper by 2 Coating with Natural Polymer Derived Materials 3 Feijie Wang1, Liqiang Wang1,*, Xinchang Zhang1, Shufeng Ma2 4 1 Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Food Advanced Manufacturing Equipment 5 Technology, School of Mechanical Engineering, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, 214122, 6 China 7 2 School of Food Engineering, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, 214122, China 8 *Email: [email protected] 9 10 Abstract: Paper is widely used as food packaging due to its good mechanical strength 11 and degradability. However, it has a relatively strong affinity for water and oil, which 12 limits its application scope. In this work, we prepare two types of coated paper to 13 investigate, the influence the air permeability and polarity on the oil resistance of the 14 coated paper. The results showed that reducing the air permeability improved the grease 15 resistance of the coated paper. High surface energy coatings also showed better oil 16 resistance because of their higher content of polar components that resulted in a higher 17 resistance to grease. The mechanical properties of the paper also improved after 18 applying the coating. These natural derived materials offer an alternative to the fluoride- 19 containing materials currently used in the market to improve the wettability of paper. 20 Keywords: coated paper · oil resistance · air permeability · polarity 21 Introduction 22 As the variety of foods containing grease is abundant, the types of oil-resistant 23 materials used in food packaging has diversified in recent years. Environmental 24 protection and safety issues continue to be important, and as a result, scholars have paid 25 increasing attention to paper packaging materials (Coltelli et al. -

4. Printing and Converting Performance

4. Printing and converting performance Paperboard converting 147 Clean edges and surfaces 155 Handling paperboard 158 Offset lithography 160 UV-offset 161 Waterless offset 162 Hybrid offset 162 Flexography 163 Screen printing 164 Digital printing 165 Gravure printing 166 Hot foil stamping 169 Embossing 171 Die-cutting & creasing 174 Lasercutting 178 Scoring 182 Creasabilty & foldability 186 Gluing 194 Binding in practice - the last link 199 Heat sealing 206 Packaging operation 203 Deep drawing 212 146 Reference Manual | IGGESUND PAPERBOARD Paperboard converting Paperboard converting Paperboard has the ability to achieve or exceed the same The increasing demands in the brand promotion process excellent image reproduction as for the best fine papers. for graphic design and the use of non-print surface enhance- Paperboard offers equal possibilities to achieve new, ment are creating innovative shapes and multi-sensory ex- challenging shapes as competing packaging materials. periences for the consumer or user who hand les the product. However, increasing demands on performance of the An understanding of the interaction between paper- material in various converting processes have become board properties and converting effi ciency is essential for evident when speeds in both printing processes and post- designers and converters, since the ultimate design of the press converting have increased. Additionally, the accept- product together with the choice of paperboard will impact ance level for impurities or slight deviations in quality in the on crucial conversion factors like printability, fl atness, and fi nal product has dropped noticeably as a result of both creasing/folding properties. Considering all the variables, end-user demands and the use of modern quality control it is probably true to say that consistency in the behaviour equipment in the various converting machines. -

VNP Guideline LCA Data for Paper and Board in the Netherlands

VNP Guidelines - LCA data for paper and board products It is of high importance that the data which isused from generic LCA databases (e.g. ecoinvent) are recent as well as representative for the kind of material used. Paper and board are complex materials that appear in different types suitable for the various applications. This document is set-up to assist LCA experts in finding the right data belonging to the type of paper and board studied. General advices: It is not advisable to use the data from European Life Cycle Database (ELCD) as these data are incomplete and also only ‘cradle to grave’: these are aggregated data hence difficult to identify where impacts come from and thus hardly usable for comparisons or to change for specific situations. Of all other generic databases ecoinvent is the most complete and current database. Other public datasets (e.g. GaBi, Base Impacts and ProBas) are less current and less easy to interpret from a user point of view. For LCA assessments on paper and board produced in the Netherlands it is essential to replace the input of the European average enery mix with input the Dutch energy mix. (NB this is not possible with ELCD as these allow no changes at all). Packaging paper Paper for corrugated board - Papier voor golfkarton Description Corrugated board (in Dutch: golfkarton) is the most commonly used transport packaging. Corrugated board consists of one or more layers of corrugated paper, in combination with one or more layers flat paper. The corrugated paper is called fluting or medium. The flat papers are called liners. -

Conservation of Coated and Specialty Papers

RELACT HISTORY, TECHNOLOGY, AND TREATMENT OF SPECIALTY PAPERS FOUND IN ARCHIVES, LIBRARIES AND MUSEUMS: TRACING AND PIGMENT-COATED PAPERS By Dianne van der Reyden (Revised from the following publications: Pigment-coated papers I & II: history and technology / van der Reyden, Dianne; Mosier, Erika; Baker, Mary , In: Triennial meeting (10th), Washington, DC, 22-27 August 1993: preprints / Paris: ICOM , 1993, and Effects of aging and solvent treatments on some properties of contemporary tracing papers / van der Reyden, Dianne; Hofmann, Christa; Baker, Mary, In: Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, 1993) ABSTRACT Museums, libraries, and archives contain large collections of pigment-coated and tracing papers. These papers are produced by specially formulated compositions and manufacturing procedures that make them particularly vulnerable to damage as well as reactive to solvents used in conservation treatments. In order to evaluate the effects of solvents on such papers, several research projects were designed to consider the variables of paper composition, properties, and aging, as well as type of solvent and technique of solvent application. This paper summarizes findings for materials characterization, degradative effects of aging, and some effects of solvents used for stain reduction, and humidification and flattening, of pigment-coated and modern tracing papers. Pigment-coated papers have been used, virtually since the beginning of papermaking history, for their special properties of gloss and brightness. These properties, however, may render coated papers more susceptible to certain types of damage (surface marring, embedded grime, and stains) and more reactive to certain conservation treatments. Several research projects have been undertaken to characterize paper coating compositions (by SEM/EDS and FTIR) and appearance properties (by SEM imaging of surface structure and quantitative measurements of color and gloss) in order to evaluate changes that might occur following application of solvents used in conservation treatments. -

Vulcan Centaur Rocket with Your Printer and Basic Tools

VULCAN CENTAUR Paper Model Kit VULCAN CENTAUR This paper rocket kit is a designed to help you build a 1:150 scale model of the Vulcan Centaur rocket with your printer and basic tools. As with all paper model kits, your level of success will depend on your precision and the time you take. It is recommended to let the glue fully dry in each step before the next. Please take care not to cut yourself and do not leave children unattended with sharp tools. Your Vulcan Centaur paper model kit will require: • 8.5” x 11” cardstock prints of the 4 pages at the end of this document, (save paper and ink by only print- ing the pattern pages 13-16 and view the instructions online) • A cutting mat • Scissors and/or an x-acto knife (children should not use x-acto or be left unattended with cutting tools and anyone attempting this kit should take care to avoid injury from cuts) • Glue (super glue or other adhesive is not necessary) • A straight edge or ruler Optional supplies: • A few toothpicks for applying glue to small areas • A small dish to hold a dollop of glue while building • A long wooden dowel or chopstick to help you apply pressure to glued areas far into the rocket body • A sharpened pencil STEP 1 Mark the booster (A) for solid rocket boosters before cutting Vulcan Centaur has the capability of using 0, 2, 4 or 6 solid rocket boosters (SRBs) for added performance. You will mark the locations for the SRBs first. -

Microfibrillated Cellulose Based Barrier Coatings for Abrasive Paper

coatings Article Microfibrillated Cellulose Based Barrier Coatings for Abrasive Paper Products Vinay Kumar 1,* , Eija Kenttä 1 , Petter Andersson 2 and Ulla Forsström 1 1 Biomass Processing and Products, VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland Ltd., 02044 Espoo, Finland; Eija.Kentta@vtt.fi (E.K.); Ulla.Forsstrom@vtt.fi (U.F.) 2 Mirka Ltd., 66850 Jeppo, Finland; [email protected] * Correspondence: vinay.kumar@vtt.fi Received: 22 October 2020; Accepted: 15 November 2020; Published: 19 November 2020 Abstract: Paper-based abrasive products are multilayer structures in which the first layer on the paper substrate is usually a latex barrier coating to prevent the migration of adhesive glue into the substrate. The high coat weight (10 g/m2) of latex barrier layers is a cause of environmental concerns. Hence, alternative materials that can provide the barrier function at lower coat weights are desired. In this work, microfibrillated cellulose (MFC) combined with poly(vinyl) alcohol (PVA) were explored as suitable alternatives to the current latex coatings. Barrier coating formulations containing PVA, MFC, and silica (SiO2) were developed and applied to a paper substrate using a rod coating method on a pilot scale. Coating quality and barrier performance were characterized using scanning electron microscope images, air permeance, surface roughness, water contact angle, KIT test, and oil Cobb measurements. The barrier coatings were also studied for adhesion to the subsequent coating layer. An optimal barrier function was achieved with the developed coatings at a low coat weight of ca. 3 g/m2. The adhesion of pure PVA and PVA-MFC barrier coatings to the subsequent coating layer was inadequate; however, silica addition was found to improve the adhesion. -

F1y3x CHAPTER 48 PAPER and PAPERBOARD

)&f1y3X CHAPTER 48 PAPER AND PAPERBOARD; ARTICLES OF PAPER PULP, OF PAPER OR OF PAPERBOARD X 48-l Notes 1. This chapter does not cover: (a) Articles of chapter 30; (b) Stamping foils of heading 3212; (c) Perfumed papers or papers impregnated or coated with cosmetics (chapter 33); (d) Paper or cellulose wadding impregnated, coated or covered with soap or detergent (heading 3401), or with polishes, creams or similar preparations (heading 3405); (e) Sensitized paper or paperboard of headings 370l to 3704; (f) Paper impregnated with diagnostic or laboratory reagents (heading 3822); (g) Paper-reinforced stratified sheeting of plastics, or one layer of paper or paperboard coated or covered with a layer of plastics, the latter constituting more than half the total thickness, or articles of such materials, other than wallcoverings of heading 48l4 (chapter 39); (h) Articles of heading 4202 (for example, travel goods); (ij) Articles of chapter 46 (manufactures of plaiting material); (k) Paper yarn or textile articles of paper yarn (section XI); (l) Articles of chapter 64 or chapter 65; (m) Abrasive paper or paperboard (heading 6805) or paper- or paperboard-backed mica (heading 6814) (paper and paperboard coated with mica powder are, however, to be classified in this chapter); (n) Metal foil backed with paper or paperboard (section XV); (o) Articles of heading 9209; or (p) Articles of chapter 95 (for example, toys, games, sports equipment) or chapter 96 (for example, buttons). 2. Subject to the provisions of note 6, headings 480l to 4805 include paper and paperboard which have been subjected to calendering, super-calendering, glazing or similar finishing, false water-marking or surface sizing, and also paper, paperboard, cellulose wadding and webs of cellulose fibers, colored or marbled throughout the mass by any method.