Chapter 5 - Architectural and Urban Patronage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

CDP of Nashik Municipal Corporation Under JNNURM

CDP of Nashik Municipal Corporation under JNNURM 3. NASHIK CITY 1. Introduction The city of Nashik is situated in the State of Maharashtra, in the northwest of Maharashtra, on 19 deg N 73 deg E coordinates. It is connected by road to Mumbai (185 kms.) and to Pune (220kms.). Rail connectivity is through the Central railway, with direct connection to Mumbai. Air link is with Mumbai, though the air service is not consistent and a proper Airport does not exist. Nashik is the administrative headquaters of Nashik District and Nashik Division. It is popularly known as the “Grape City” and for its twelve yearly ‘Sinhasta Kumbh Mela’, it is located in the Western Ghats on the banks of river Godavari, and has become a center of attraction because of its beautiful surroundings and cool and pleasant climate. Nashik has a personality of its own due to its mythological, historical, social and cultural importance. The city, vibrant and active on the industrial, political, social and cultural fronts, has influenced the lives of many a great personalities. The Godavari River flows through the city from its source in the holy place of Tribakeshwar, cutting the city into two. Geographical proximity to Mumbai (Economic capital of India) and forming the golden trangle with Mumbai & Pune has accelerated its growth. The developments of the past two decades has completely transformed this traditional pilgrimage center into a vibrant modern city, and it is poised to become a metropolis with global links. New Nashik has emerged out of the dreams, hard work and enterprising spirit of local and migrant populace. -

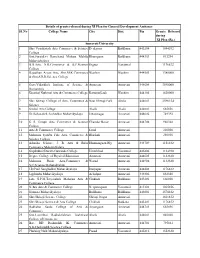

Maharashtra State Boatd of Sec & H.Sec Education Pune

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE PAGE : 1 College wise performance ofFresh Regular candidates for HSC 2021 Candidates passed College No. Name of the collegeStream Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 01.01.001 Z.P.BOYS JUNIOR COLLEGE, AKOLA SCIENCE 66 66 66 0 0 0 66 100.00 27050803901 ARTS 14 14 7 7 0 0 14 100.00 COMMERCE 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 100.00 TOTAL 81 81 74 7 0 0 81 100.00 01.01.002 GOVERNMENT TECHNICAL COLLEGE, AKOLA SCIENCE 17 17 16 1 0 0 17 100.00 27050117183 TOTAL 17 17 16 1 0 0 17 100.00 01.01.003 R.L.T. SCIENCE COLLEGE, AKOLA CIVIL LINE SCIENCE 544 544 543 1 0 0 544 100.00 27050117184 TOTAL 544 544 543 1 0 0 544 100.00 01.01.004 SHRI.SHIVAJI ARTS COMMERCE & SCIENCE SCIENCE 238 238 238 0 0 0 238 100.00 27050117186 COLLEGE,AKOLA ARTS 160 160 60 100 0 0 160 100.00 COMMERCE 183 183 110 73 0 0 183 100.00 TOTAL 581 581 408 173 0 0 581 100.00 01.01.005 SMT L.R.T. COMMERCE COLLEGE , AKOLA COMMERCE 761 761 748 12 1 0 761 100.00 27050117187 TOTAL 761 761 748 12 1 0 761 100.00 01.01.006 SITABAI ARTS COLLEGE, AKOLA CIVIL LINE ROAD SCIENCE 7 7 7 0 0 0 7 100.00 27050119003 ARTS 111 111 47 61 3 0 111 100.00 COMMERCE 105 105 97 8 0 0 105 100.00 MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE PAGE : 2 College wise performance ofFresh Regular candidates for HSC 2021 Candidates passed College No. -

THE Tl1ird ENGLISH EMBASSY to POON~

THE Tl1IRD ENGLISH EMBASSY TO POON~ COMPRISING MOSTYN'S DIARY September, 1772-February, 1774 AND MOSTYN'S LETTERS February-177 4-Novembec- ~~:;, EDITED BY ]. H. GENSE, S. ]., PIL D. D. R. BANAJI, M. A., LL. B. BOMBAY: D. B. TARAPOREV ALA SONS & CO. " Treasure House of Books" HORNBY ROAD, FORT· COPYRIGHT l934'. 9 3 2 5.9 .. I I r\ l . 111 f, ,.! I ~rj . L.1, I \! ., ~ • I • ,. "' ' t.,. \' ~ • • ,_' Printed by 1L N. Kulkarni at the Katnatak Printing Pr6SS, "Karnatak House," Chira Bazar, Bombay 2, and Published by Jal H. D. Taraporevala, for D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Hornby Road, Fort, Bombay. PREFACE It is well known that for a hundred and fifty years after the foundation of the East India Company their representatives in ·India merely confined their activities to trade, and did not con· cern themselves with the game of building an empire in the East. But after the middle of the 18th century, a severe war broke out in Europe between England and France, now known as the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), which soon affected all the colonies and trading centres which the two nations already possessed in various parts of the globe. In the end Britain came out victorious, having scored brilliant successes both in India and America. The British triumph in India was chiefly due to Clive's masterly strategy on the historic battlefields in the Presidencies of Madras and Bengal. It should be remembered in this connection that there was then not one common or supreme authority or control over the three British establishments or Presidencies of Bengal, Madras and Bombay. -

Climate Change, Mangrove & Sustainable

ISBN: 978-93-88901-10-9 June 2020 Climate Change, Mangrove & Sustainable Management Edited by Dr. D. L. Bharmal Dr. U. L. Dethe Dr. N. M. Desai Dr. U. R. Pawar Dr. V. T. Aparadh Bhumi Publishing malarClimate Change, Mangroves and Sustainable Management 2020 Sr. Authors Title Page No. No. 1. Dr. Dilip Kuralapkar Mangroves: Unique Ecosystems 1 2. Dr. K. Kathiresan Mangroves of India : Globally Unique 4 3. Dr. Vinod Dhargalkar Mangroves to Combat Climate Change 6 4. Dr. Subir Ghosh Climate change and Sustainable Livelihood in Coastal 10 Maharashtra 5. Dr. Bambang Widigdo Hidden Contribution of Shrimp Farm on Blue Carbon 31 Dynamics 6. Dr. Wah Wah Min Global distribution of crabs in mangrove forests 37 7. Abhinav A. Mali Ecological and Economic Services of Mangroves 39. and Ajit M. Tiwari 8. Aimana Afrin and Mangrove Ecosystem 40. Dr. C. Hemavathi 9. Ajit M. Tiwari and Mumbai's Vanishing Mangroves: An Alarming 41. Abhinav A. Mali Situation 10. Dr. Ajit Kumar Jaiswal Mangroves Support Biodiversity and Fish Nurseries, 42. Reduce Erosion, Protect Coasts, Regulate The Climate and Provide Resources 11. Dr. Alka Inamdr Mangroves: The Backbone of Ecosystems 43. 12. Amarja Nitin Joshi Mangrove Resources 44. 13. Amrendra Kumar Aerosol Characterization Over Mangrove Forest 45. and Dr. Ningombam Region In India: A Review Linthoingambi Devi 14. Anand Billade Assessment Of Coastal Blue Carbon From The 46. and Dr. Mahesh Shindikar Mangroves Of Greater Mumbai 15. Aniruddha S. Deshpande Status Of Mangroves In India – A Review 47. and S. N. Malode 16. Dr. Anita M. Katgaye Service Of Mangroves For The Benefit of People And 48. -

Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. Prof. V. Sakunthalamma Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. & Prof. Susmita Basu Majumdar Dept. of AIHC, University of Calcutta. Dr. Mahesh A. Kalra Curator, The Asiatic Society of Mumbai.. Prof. Susmita Basu Majumdar Dept. of AIHC, University of Calcutta. 1 Component-I (B) – Description of module : Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Indian Numismatics Module Name/Title Coinage of the Marathas under Chhatrapati Shivaji and the Maratha Confederacy Module Id IC / NMST / 32 Pre-requisites Maratha History and their economy Objectives To introduce types of Maratha Coinages issued at different periods of Maratha History. To bring in focus the volume of each coin type issued from the period of Chhatrapati Shivaji till the loss of Maratha power in 1818. Keywords Maratha / Chhatrapati Shivaji / Sardeshmukh E-text (Quadrant-I) : 1. Introduction “Dakhan, the son of Hind had three sons and the country of Dakhan was divided among them. Their names are Marath, Kanhar (Kannada) and Tilang. At present, these races reside in the Dakhan.” - Muhammad Qasim Hindu Shah ‘Ferishta’ in his Gulshan-i- Ibrahimipopularly called Taa’rikh-i-Ferishta. This statement by Ferishta in his sixteenth century work on the History of India clearly establishes the Marathas as the native people of Western Dakkan who rose to power under the genius of two medieval rulers of the Deccan, Mallik Ambar who effectively armed the Marathas and ChhatrapatiShivaji who effectively used this mobilisation to establish a small compact state, the Maharashtra Swarajya in the middle half of the seventeenth century. This kingdom situated firmly in the Deccan plateau and the Konkan region in North-Western Maharashtra grew southwards and became the major opponent to all Indo-Islamic powers ranging from the local Deccan Sultanates and the invading Mughals who engulfed the Sultanates one by one creating a new province of Mughal Deccan. -

Car Package New Size 2

Tour Code: WM 02 Sri Ashtavinayak Yatra Malaysia 3 Days / 2Nights ` 11,999/- & Departure :These tours can be arranged any time during the year. Places Covered : Pune - Narayanpur - Jejuri - Morgaon - Siddhatek - Singapor e Theur - Ranjangaon - Lenyadri - Ozer - Mahad - Pali - Pune Shree Kalaram Temple, Panchavati gapore Merlion, Sin Day 01: Pune -Narayanpur - Pune Pick-up from Pune Railway Station / Airport and transfer to Hotel. After fresh ups, proceed to Ashtavinayak Yatra which covers darshan at Eight Holy shrines of Lord Shri Ganapati in Mahrashtra. The Yatra starts from Mayureshwar of MORGAON (90Kms / 2Hrs) en-route visit NARAYANPUR (abode of Lord Tirupati Balaji), JEJURI (Shri Khandoba), SIDDHATEK (Lord Sidhi Vinayak) (75Kms/ 1.5Hrs), to THEUR (Shree Chintamani) and return back to Pune(110Kms / 2Hrs) Overnight stay. Mala Day 02: Ranjangaon - Lenyadri - Ozer - Pune ysia Eye After breakfast Proceed to RANJANGAON (Lord Mahaganapati) , Kua lalum (55Kms /1Hr), later proceed to OZER (Lord Vigneswar) (90Kms / pur 2Hrs), LENYADRI (Lord Girijatmaj Vinayaka) back to Pune (100Kms /2Hrs) overnight Stay. Day 03: Mahad - Pali - Pune After breakfast check out from Hotel Proceed to MAHAD (Lord Varad Vinayak)(90Kms /2Hrs), PALI (Shri Ballaleshwar) (40Kms /1Hr). Later Departure to Pune (125Kms /2Hrs) and transfer to Railway Station / Airport for return journey. Tour Concludes. Package cost per person in INR ( ` ) Category Type of Vehicles Standard Deluxe 2 Pax 11,999/- 13,199/- By Car 3 - 4 Pax 8,999/- 10,199/- 4 - 5 Pax By Innova 9,229/- 10,499/- Please contact us further details : 6 - 7 Pax 6,999/- 8,299/- Tempo Traveller 8 - 9 Pax 7,299/- 8,599/- * Fares from 21st December to 5th January are available on request. -

At Glance Nashik Division

At glance Nashik Division Nashik division is one of the six divisions of India 's Maharashtra state and is also known as North Maharashtra . The historic Khandesh region covers the northern part of the division, in the valley of theTapti River . Nashik Division is bound by Konkan Division and the state of Gujarat to the west, Madhya Pradesh state to the north, Amravati Division and Marathwada (Aurangabad Division) to the east, andPune Division to the south. The city of Nashik is the largest city of this division. • Area: 57,268 km² • Population (2001 census): 15,774,064 • Districts (with 2001 population): Ahmednagar (4,088,077), Dhule (1,708,993), Jalgaon (3,679,93 6) Nandurbar (1,309,135), Nashik 4,987,923 • Literacy: 71.02% • Largest City (Population): Nashik • Most Developed City: Nashik • City with highest Literacy rate: Nashik • Largest City (Area): Nashik * • Area under irrigation: 8,060 km² • Main Crops: Grape, Onion, Sugarcane, Jowar, Cotton, Banana, Chillies, Wheat, Rice, Nagli, Pomegranate • Airport: Nasik [flights to Mumbai] Gandhinagar Airport , Ozar Airport • Railway Station:Nasik , Manmad , Bhusaval History of administrative districts in Nashik Division There have been changes in the names of Districts and has seen also the addition of newer districts after India gained Independence in 1947 and also after the state of Maharashtra was formed. • Notable events include the creation of the Nandurbar (Tribal) district from the western and northern areas of the Dhule district. • Second event include the renaming of the erstwhile East Khandesh district as Dhule , district and West Khandesh district as Jalgaon . • The Nashik district is under proposal to be divided and a separate Malegaon District be carved out of existing Nashik district with the inclusion of the north eastern parts of Nashik district which include Malegaon , Nandgaon ,Chandwad ,Deola , Baglan , and Kalwan talukas in the proposed Malegaon district. -

4. Maharashtra Before the Times of Shivaji Maharaj

The Coordination Committee formed by GR No. Abhyas - 2116/(Pra.Kra.43/16) SD - 4 Dated 25.4.2016 has given approval to prescribe this textbook in its meeting held on 3.3.2017 HISTORY AND CIVICS STANDARD SEVEN Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, Pune - 411 004. First Edition : 2017 © Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, Reprint : September 2020 Pune - 411 004. The Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research reserves all rights relating to the book. No part of this book should be reproduced without the written permission of the Director, Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, ‘Balbharati’, Senapati Bapat Marg, Pune 411004. History Subject Committee : Cartographer : Dr Sadanand More, Chairman Shri. Ravikiran Jadhav Shri. Mohan Shete, Member Coordination : Shri. Pandurang Balkawade, Member Mogal Jadhav Dr Abhiram Dixit, Member Special Officer, History and Civics Shri. Bapusaheb Shinde, Member Varsha Sarode Shri. Balkrishna Chopde, Member Subject Assistant, History and Civics Shri. Prashant Sarudkar, Member Shri. Mogal Jadhav, Member-Secretary Translation : Shri. Aniruddha Chitnis Civics Subject Committee : Shri. Sushrut Kulkarni Dr Shrikant Paranjape, Chairman Smt. Aarti Khatu Prof. Sadhana Kulkarni, Member Scrutiny : Dr Mohan Kashikar, Member Dr Ganesh Raut Shri. Vaijnath Kale, Member Prof. Sadhana Kulkarni Shri. Mogal Jadhav, Member-Secretary Coordination : Dhanavanti Hardikar History and Civics Study Group : Academic Secretary for Languages Shri. Rahul Prabhu Dr Raosaheb Shelke Shri. Sanjay Vazarekar Shri. Mariba Chandanshive Santosh J. Pawar Assistant Special Officer, English Shri. Subhash Rathod Shri. Santosh Shinde Smt Sunita Dalvi Dr Satish Chaple Typesetting : Dr Shivani Limaye Shri. -

Chapter Bxqht

CHAPTER BXQHT Conclusion 26i c h a p t e r e i g h t Shivajl was aware of the sovereignty that he as the Chhatrapatl and his kingdcxr. the Swarajya enjoyed* He had all the powers in the Swarajya and had a thorough control over the administration in the kingdom. His sons, though aware of the sovereignty of the kingdom, started the practice of Informally delegating their power to others* Rajararr;, the ^ 1 second son of Shivaji, most probably on the counsel of his / advisers,! started the practice of granting land for military ) services, in face of the massive Mughal invasion* His ultimate successor £hahu, the son of Sambhaji, was utterly unsuitable to lead a turbulent people like the Marathas* The character and the policy of 3hahu accentuated the trend of decentralisaticm* The saranjam system initiated by Rajaram was conti^nued by Shahu* ~ ---- - ^ Though the Marathas knew the jam systemi of the Kuhamiradans from within, the saranjam system of the Marathas had its own peculiarities which vitally affected the constitutional, the financial, the administrative and the military 'systems* of the Marathas* The saranjair. was the assignment of land to a person for military services* There was, therefore, a donor who assigned 262 land to a donee* The donor in the saranjair system, ultimately, in the formal sense was the Chhatrapati* Iftider an inactive and non-martial ruler like- Shahu, Peshwa Bajirao gained power not because of any inherent strength in the "office" of the ieshwa, but because Bajirao was active and rrartial* The sardari of the army was not given to Bajirao; it was givn to Chiroaji, his brother* Both were strcxig and selfish and, therefore, audacious towards the Chhatrapati* Peshwa Bajirao was given seventeen villages while giving the robes of the Peshwaship; at the time of his death he left behind saranjam worth rupees thirty lacs* iie, moreover, left behind his own sardars, who <iould be loyal to the Peshwa alone. -

General Development Assitance Sl

Details of grants released during XI Plan for General Development Assitance Sl. No College Name City Dist. Pin Grants Released during XI Plan (Rs.) Amravati University 1 Shri Vyankatesh Arts Commerce & Science Deulgaon Buldhana 443204 1084392 College 2 Smt.Surajdevi Ramchand Mohata Mahila Khamgaon Buldhana 444303 813294 Mahavidyalaya 3 B.B.Arts, N.B.Commerce & B.P.Science Digras Yavatmal 1176832 College 4 Rajasthan Aryan Arts, Shri.M.K.Commerce Washim Washim 444505 1380000 & Shri.S.R.R.Science College 5 Govt.Vidarbha's Institute of Science & Amravati Amravati 444604 3590000 Humanities 6 Kisanlal Nathmal Arts & Commerce College Karanja(Lad) Washim 444105 1620000 7 Shri Shivaji College of Arts, Commerce & Near Shivaji Park Akola 444001 2596154 Science 8 Sitabai Arts College Akola Akola 444001 665856 9 Dr.Babasaheb Ambedkar Mahavidyalaya Uttamnagar Amravati 444602 749392 10 G S Tompe Arts Commerce & Science Chandur Bazar Amravati 444704 960368 College 11 Arts & Commerce College Jarud Amravati 220000 12 Mahatma Jyotiba Fule Arts, Commerce & Bhatkuli Amravati 280000 Science College 13 Adarsha Science, J. B. Arts & Birla Dhamangaon Rly Amravati 444709 1151832 Commerce Mahavidyalaya 14 Gopikabai Sitaram Gawande College Umarkhed Yavatmal 445206 1134390 15 Degree College of Physical Education Amravati Amravati 444605 1132320 16 Mahatma Phule Arts,Commerce & Warud Amravati 444906 1132320 S.C.Science Mahavidyalaya 17 J.D.Patil Sangludkar Mahavidyalaya Daryapur Amravati 444803 1176832 18 Jagdamba Mahavidyalaya Achalpur Amravati 444806 832320 19 Late S.P.M.Tatyasaheb Mahajan Arts & Chikhali Buldhana 443201 660000 Commerce College 20 Nehru Arts & Commerce College Nerparsopant Yavatmal 415102 1065856 21 Jijamata Mahavidyalaya Buldhana Buldhana 443001 1576832 22 Shri.Shivaji Science College Shivaji Nagar Amravati 1601832 23 Shri Shivaji Science & Arts College Chikhali Buldana 443201 1176832 24 Radhabai Sarda College of Arts & Anjangaon Amravati 444705 665856 Commerce 25 Smt.Laxmibai Radhakrishnan Toshniwal Akola Akola 444001 840000 College of Commerce 26 Bar. -

College Name a Mirza Vjnt Sec & Hr Sec Ashram Shala A

COLLEGE NAME A MIRZA VJNT SEC & HR SEC ASHRAM SHALA A.GULABRAOJI GAWANDE JR COLLEGE BORGAON ABASAHEB PARWEKAR JUNIOR COLLEGE ABDUL RAJIK URDU HIGH SEC SCHOOL ABDUL RASHID MEMORI- AL,URDU SEC.& HIGH ABHINAV JR COLLEGE JANUNA,TQ-NANDGAON ABHYANKAR GIRLS JUNIOR COLLEGE ADARSH ARTS & COMM JUNIOR COLLEGE ADARSH ARTS HIGH SEC SCHOOL,SHIDOLA ADARSH HIGH SEC. SCHOOL,UMALI ADARSH JR COLLEGE AKOT ROAD ADARSH JR COLLEGE TIWRI ADARSH JUNIOR COLLEGE ,MUKUTBAN ADARSH KANYA JR COLLEGE MURTIZAPUR ADARSH SEC & HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL ADARSH SEC & HR SEC SCH. DHANORA GURAV ADARSHA ARTS SCI & BIRLA COMM COLLEGE ADARSHA JR COLLEGE SINGAON JAHANGIR ADARSHA JR SCI COLL CHIKHALI ADARSHA JR SCIENCE COLLEGE,KAPSHI RD ADARSHA KALA HIGH SEC.SCHOOL,MARDI ADARSHA MADHYA & UCHCHA MADHYA VIDYA ADARSHA SEC. & HIGH SEC. SCHOOL ,WANI ADIVASI HIGH SEC SCHOOL,SALONA ADIVASI HIGHER SEC SCHOOL TUNAKI BK. ADV SHANKARRAO RATHOD HR SEC SCHOOL AHILYABAI HOLKAR HR SEC GIRLS SCHOOL AIDED JUNIOR COLLEGE AJGAR HUSAIN URDU JR COLLEGE KHOLAPUR AJHAR FARKHANDA URDU JR COLLEGE,GHODEGAO AJIT DADA PAWAR JR COL RANI AMRAVATI AKOLA ARTS COM & SCI NEW JUNIOR COLLEGE AKOT JUNIOR COLLEGE KRISHI, AKOT ALI ALLANA URDU SCI. HIGH SEC.SCHOOL, ALKHAIR URDU JR COLL TALEGAON MOHNA ALPALAH SHAMIM AZAD URDU H.SEC SCHOOL AMAR JUNIOR COLLEGE AMDAPUR AMARSINH JUNIOR COLLEGE AMBIKA HR SEC SCHOOL MANGLADEVI TQ NER AMINA AJIJ URDU SCI. HIGH SEC.SCHOOL, AMINA URDU HIGH SECH SCHOOL,PINJAR AMOLAKCHAND MAHA- VIDYALAYA ANAND JUNIOR COLLEGE WALGAON ANANTRAO SARAF JR. COLLEGE SHELAPUR BK ANGLO HINDI JUNIOR COLLEGE ANJUMAN ANWAL ESLAM JR COLL OF SCIENCE ANJUMAN JUNIOR COLLEGE ANJUMAN URDU HIGH & SCI.