Chapter Bxqht

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

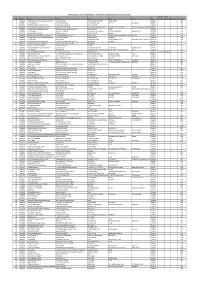

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

Maharashtra State Boatd of Sec & H.Sec Education Pune

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE PAGE : 1 College wise performance ofFresh Regular candidates for HSC 2021 Candidates passed College No. Name of the collegeStream Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 01.01.001 Z.P.BOYS JUNIOR COLLEGE, AKOLA SCIENCE 66 66 66 0 0 0 66 100.00 27050803901 ARTS 14 14 7 7 0 0 14 100.00 COMMERCE 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 100.00 TOTAL 81 81 74 7 0 0 81 100.00 01.01.002 GOVERNMENT TECHNICAL COLLEGE, AKOLA SCIENCE 17 17 16 1 0 0 17 100.00 27050117183 TOTAL 17 17 16 1 0 0 17 100.00 01.01.003 R.L.T. SCIENCE COLLEGE, AKOLA CIVIL LINE SCIENCE 544 544 543 1 0 0 544 100.00 27050117184 TOTAL 544 544 543 1 0 0 544 100.00 01.01.004 SHRI.SHIVAJI ARTS COMMERCE & SCIENCE SCIENCE 238 238 238 0 0 0 238 100.00 27050117186 COLLEGE,AKOLA ARTS 160 160 60 100 0 0 160 100.00 COMMERCE 183 183 110 73 0 0 183 100.00 TOTAL 581 581 408 173 0 0 581 100.00 01.01.005 SMT L.R.T. COMMERCE COLLEGE , AKOLA COMMERCE 761 761 748 12 1 0 761 100.00 27050117187 TOTAL 761 761 748 12 1 0 761 100.00 01.01.006 SITABAI ARTS COLLEGE, AKOLA CIVIL LINE ROAD SCIENCE 7 7 7 0 0 0 7 100.00 27050119003 ARTS 111 111 47 61 3 0 111 100.00 COMMERCE 105 105 97 8 0 0 105 100.00 MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE PAGE : 2 College wise performance ofFresh Regular candidates for HSC 2021 Candidates passed College No. -

Chapter 5 - Architectural and Urban Patronage

CHAPTER 5 - ARCHITECTURAL AND URBAN PATRONAGE In 1779 CE Ahilyābāī Hoḷkar sent a letter to Gopikābāī Peśvā, grandmother of the then Peśvā, Savāī Mādhavrāv and the wife of Nānāsāheb Peśvā. Some years before, Gopikābāī, who was staying at Nāśik, had constructed a kuṅda and ghāṭ on the Godāvarī River known respectively as Rāmkuṅda and Rāmghāṭ. Ahilyābāī wrote to Gopikābāī requesting for permission to repair and rebuild the same in a more artistic manner. Gopikābāī flatly refused any such permission saying that the kuṅda and ghāṭ were meant to preserve her memories which she did not want to be destroyed (Sathe, 2013, p. 143). Ahilyābāī retaliated by not sending the sarees that Gopikābāī had requested from Maheshwar. It was an act of what Bourdieu has termed as ‘symbolic violence’, a strategy employed by those having legitimacy in the social field to maintain their positions from any competition. Clearly, Gopikābāī saw Ahilyābāī’s intervention as a threat to her authority. This apparently simple event shows the acute awareness that patrons had, of the power of architecture in consolidating their social positions. They used architecture consciously to further their social and political aims. What purposes did the construction projects serve beyond the mere function? How were buildings used by the agents to assert authority and consolidate social positions? Can we trace any thematic continuity between the patronage of preceding centuries and the eighteenth century? This chapter attempts to answer such questions by focusing on patronage and matronage in the study area. Patronage and its relationship with architecture has been an important concern for a number of years in Historical studies. -

THE Tl1ird ENGLISH EMBASSY to POON~

THE Tl1IRD ENGLISH EMBASSY TO POON~ COMPRISING MOSTYN'S DIARY September, 1772-February, 1774 AND MOSTYN'S LETTERS February-177 4-Novembec- ~~:;, EDITED BY ]. H. GENSE, S. ]., PIL D. D. R. BANAJI, M. A., LL. B. BOMBAY: D. B. TARAPOREV ALA SONS & CO. " Treasure House of Books" HORNBY ROAD, FORT· COPYRIGHT l934'. 9 3 2 5.9 .. I I r\ l . 111 f, ,.! I ~rj . L.1, I \! ., ~ • I • ,. "' ' t.,. \' ~ • • ,_' Printed by 1L N. Kulkarni at the Katnatak Printing Pr6SS, "Karnatak House," Chira Bazar, Bombay 2, and Published by Jal H. D. Taraporevala, for D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Hornby Road, Fort, Bombay. PREFACE It is well known that for a hundred and fifty years after the foundation of the East India Company their representatives in ·India merely confined their activities to trade, and did not con· cern themselves with the game of building an empire in the East. But after the middle of the 18th century, a severe war broke out in Europe between England and France, now known as the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), which soon affected all the colonies and trading centres which the two nations already possessed in various parts of the globe. In the end Britain came out victorious, having scored brilliant successes both in India and America. The British triumph in India was chiefly due to Clive's masterly strategy on the historic battlefields in the Presidencies of Madras and Bengal. It should be remembered in this connection that there was then not one common or supreme authority or control over the three British establishments or Presidencies of Bengal, Madras and Bombay. -

Shivaji the Founder of Maratha Swaraj

26 B. I. S. M. Puraskrita Grantha Mali, No. SHIVAJI THE FOUNDER OF MARATHA SWARAJ BY C. V. VAIDYA, M. A., LL. B. Fellow, University of Bombay, Vice-Ctianct-llor, Tilak University; t Bharat-Itihasa-Shamshndhak Mandal, Poona* POON)k 1931 PRICE B8. 3 : B. Printed by S. R. Sardesai, B. A. LL. f at the Navin ' * Samarth Vidyalaya's Samarth Bharat Press, Sadoshiv Peth, Poona 2. BY THE SAME AUTHOR : Price Rs* as. Mahabharat : A Criticism 2 8 Riddle of the Ramayana ( In Press ) 2 Epic India ,, 30 BOMBAY BOOK DEPOT, BOMBAY History of Mediaeval Hindu India Vol. I. Harsha and Later Kings 6 8 Vol. II. Early History of Rajputs 6 8 Vol. 111. Downfall of Hindu India 7 8 D. B. TARAPOREWALLA & SONS History of Sanskrit Literature Vedic Period ... ... 10 ARYABHUSHAN PRESS, POONA, AND BOOK-SELLERS IN BOMBAY Published by : C. V. Vaidya, at 314. Sadashiv Peth. POONA CITY. INSCRIBED WITH PERMISSION TO SHRI. BHAWANRAO SHINIVASRAO ALIAS BALASAHEB PANT PRATINIDHI,B.A., Chief of Aundh In respectful appreciation of his deep study of Maratha history and his ardent admiration of Shivaji Maharaj, THE FOUNDER OF MARATHA SWARAJ PREFACE The records in Maharashtra and other places bearing on Shivaji's life are still being searched out and collected in the Shiva-Charitra-Karyalaya founded by the Bharata- Itihasa-Samshodhak Mandal of Poona and important papers bearing on Shivaji's doings are being discovered from day to day. It is, therefore, not yet time, according to many, to write an authentic lifetof this great hero of Maha- rashtra and 1 hesitated for some time to undertake this work suggested to me by Shrimant Balasaheb Pant Prati- nidhi, Chief of Aundh. -

Share Liable to Be Transferres to IEPF Lying in UNCLAIMED SUSPENSE ACCOUNT

SHARES LIABLE TO BE TRANSFERRED TO IEPF LYING IN UNCLAIMED SUSPENSE ACCOUNT Second Third S.No Folio Name Add1 Add2 Add3 Add4 PIN Holder Holder Delivery Shares 1 000010 HARENDRA KUMAR MAGANLAL MEHTA C/O SHRINAGAR 1198 CHANDNI CHOWK DELHI 110006 110006 0 480 2 000013 N S SUNDARAM 9B CLEMENS ROAD POST BOX NO 480 VEPERY CHENNAI 7 600007 0 210 3 000024 BABUBHAI RANCHHODLAL SHAH 153-D KAMLA NAGAR, DELHI-110 007. 110007 0 210 4 000036 CHANDRAKANT RAOJIBHIA AMIN M/S APAJI AMIN & CO CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS 1299/B/1 LAL DARWAJA NEAR DR K M SHAH S HOSPITAL380001 0 615 5 000042 CHAMPAKLAL ISHWARLAL SHAH 2/4456 SHIVDAS ZAVERZIS SORRI SAGRAMPARA SURAT 395002 0 7 6 000048 K V SIVANNA 181/50 4TH CROSS VYALIKAVAL EXTENSION P O MALLESWARAM BANGALORE 3 560003 0 210 7 000052 NARAYANDAS K DAGA KRISHNA MAHAL MARINE DRIVE MUMBAI 1 400001 0 210 8 000080 MANGALACHERIL SAMUEL ABRAHAM AVT RUBBER PRODUCTS LTD PLOT NO 14-C COCHIN EXPORT PROCESSING ZONE COCHIN 682030 0 502 9 000089 RAMASWAMY PILLAI RAMACHANDRAN 1 PATULLOS ROAD MOUNT ROAD CHENNAI 2 600002 0 435 10 000134 P A ANTONY JOSEALAYAM MUNDAKAPADAM P O ATHIRAMPUZHA DIST-KOTTAYAM KERALA STATE686562 0 210 11 000168 S KOTHANDA RAMAN NAYANAR 11 MADHAVA PERUMAL KOVIL ST MYLAPORE CHENNAI 600004 0 435 12 000171 JETHALAL PANJALAL PAREKH D K ARTS &SCIENCE COLLEGE JAMNAGAR 361001 0 67 13 000173 SAJINI TULSIDAS DASWANI 24 KAHUN ROAD POONA 1 411001 0 1510 14 000226 KRISHNAMOORTY VENNELAGANTI HEAD CASHIER STATE BANK OF INDIA P O GUDUR DIST NELLORE 524101 0 435 15 000227 HAR PRASAD PROPRIETOR M/S GORDHAN DASS SHEONARAINKATRA -

Chapter Three Lonavla

CHAPTER THREE LONAVLA - A REGIONAL PROFILE 3.1 Presenting Lonavla 3.2 Historical Perspective of Lonavla. 3.3 Location and Physiography of Lonavla. 3.4 Population 3.5 Climate 3.6 The Town 3.7 Occupational Structure 3.8 Land use of Lonavla 3.9 Important Tourist Destinations 55 3,1 Presenting Lonavla This chapter aims to highlight in brief the physical and demographic background of Lonavla and to show how it is a tourist place and how the local population, occupational structure and land use of Lonavla make it most important tourist destination. In short this chapter highlights the regional profile of Lonavla as a tourist centre. One of the most important hill stations in the state of Maharashtra is Lonavla. It is popularly known as the Jewel of the Sahayadri Mountains.Lonavla is set amongst the Sylvan surrounding of the w'estem ghats and is popular gateway from Mumbai and Pune. It also serves as a starting point for tourists interested in visiting the famous ancient Buddhist rock - cut caves of Bhaja and Karla, which are located near this hill station. It has some important Yoga Centres near it. There are numerous lakes around Lonavla Tungarli, Bhushi, and Walvan, Monsoon and adventure seekers can try their hand at rock climbing at the Duke’s Nose peak and other locations in the Karla hills and Forts. In order to make the travel tour to Lonavla even more joyful the right kind of accommodation is provided by the Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation (M.T.D.C.). The various hotels packages offer the best of facilities. -

Madhavrao Peshwe and Nizam Relationship: a New Approach

World Wide Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development WWJMRD 2017; 3(12): 128-130 www.wwjmrd.com International Journal Peer Reviewed Journal Madhavrao Peshwe and Nizam Relationship: A New Refereed Journal Indexed Journal Approach UGC Approved Journal Impact Factor MJIF: 4.25 e-ISSN: 2454-6615 Satpute Rajendra Bhimaji Satpute Rajendra Bhimaji Abstract Head, Department of History In the history of Maratha, place of Madhavrao Peshwa has highest status. In the age of 16yrs. he got Arts and Commerce College, cloths of Peshwa, that time Maratha state had suffered from many problems. So preventing attack of Satara (Maharashtra), India Hyder Ali, Madhavrao did treaty with Nizam in 1766. In treaty with Nizam Madhavrao had many purposes behind that. Madhavrao did treaty with Nizam because of overwhelming on Janoji Bhosale, Babuji Naik and Raghobadada. In south Nizam, Maratha, Hyder Ali and British these were four main powers in 18th century, in those Maratha power was more stronger than any other. Sherjang, a sardar th of Nizam had played a vital role in occurring this treaty. In 18 century, to gain success in colonialism policy of Maratha state,it was need to prevent attack of Nizam and Hyder Ali. So firstly Peshwa did struggle with Nizam after that he made friendly relationship with him. As like Madhavrao took expeditions on Hyder Ali and did use of these expeditions, he forcedHyder Ali to become powerless in Shriranpattanam. Maratha state and Hyderabad both states got military and economic benefits by this friendly relationship. As a result, peace created in south and it was helpful to economic development of Maratha state. -

Climate Change, Mangrove & Sustainable

ISBN: 978-93-88901-10-9 June 2020 Climate Change, Mangrove & Sustainable Management Edited by Dr. D. L. Bharmal Dr. U. L. Dethe Dr. N. M. Desai Dr. U. R. Pawar Dr. V. T. Aparadh Bhumi Publishing malarClimate Change, Mangroves and Sustainable Management 2020 Sr. Authors Title Page No. No. 1. Dr. Dilip Kuralapkar Mangroves: Unique Ecosystems 1 2. Dr. K. Kathiresan Mangroves of India : Globally Unique 4 3. Dr. Vinod Dhargalkar Mangroves to Combat Climate Change 6 4. Dr. Subir Ghosh Climate change and Sustainable Livelihood in Coastal 10 Maharashtra 5. Dr. Bambang Widigdo Hidden Contribution of Shrimp Farm on Blue Carbon 31 Dynamics 6. Dr. Wah Wah Min Global distribution of crabs in mangrove forests 37 7. Abhinav A. Mali Ecological and Economic Services of Mangroves 39. and Ajit M. Tiwari 8. Aimana Afrin and Mangrove Ecosystem 40. Dr. C. Hemavathi 9. Ajit M. Tiwari and Mumbai's Vanishing Mangroves: An Alarming 41. Abhinav A. Mali Situation 10. Dr. Ajit Kumar Jaiswal Mangroves Support Biodiversity and Fish Nurseries, 42. Reduce Erosion, Protect Coasts, Regulate The Climate and Provide Resources 11. Dr. Alka Inamdr Mangroves: The Backbone of Ecosystems 43. 12. Amarja Nitin Joshi Mangrove Resources 44. 13. Amrendra Kumar Aerosol Characterization Over Mangrove Forest 45. and Dr. Ningombam Region In India: A Review Linthoingambi Devi 14. Anand Billade Assessment Of Coastal Blue Carbon From The 46. and Dr. Mahesh Shindikar Mangroves Of Greater Mumbai 15. Aniruddha S. Deshpande Status Of Mangroves In India – A Review 47. and S. N. Malode 16. Dr. Anita M. Katgaye Service Of Mangroves For The Benefit of People And 48. -

Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. Prof. V. Sakunthalamma Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. & Prof. Susmita Basu Majumdar Dept. of AIHC, University of Calcutta. Dr. Mahesh A. Kalra Curator, The Asiatic Society of Mumbai.. Prof. Susmita Basu Majumdar Dept. of AIHC, University of Calcutta. 1 Component-I (B) – Description of module : Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Indian Numismatics Module Name/Title Coinage of the Marathas under Chhatrapati Shivaji and the Maratha Confederacy Module Id IC / NMST / 32 Pre-requisites Maratha History and their economy Objectives To introduce types of Maratha Coinages issued at different periods of Maratha History. To bring in focus the volume of each coin type issued from the period of Chhatrapati Shivaji till the loss of Maratha power in 1818. Keywords Maratha / Chhatrapati Shivaji / Sardeshmukh E-text (Quadrant-I) : 1. Introduction “Dakhan, the son of Hind had three sons and the country of Dakhan was divided among them. Their names are Marath, Kanhar (Kannada) and Tilang. At present, these races reside in the Dakhan.” - Muhammad Qasim Hindu Shah ‘Ferishta’ in his Gulshan-i- Ibrahimipopularly called Taa’rikh-i-Ferishta. This statement by Ferishta in his sixteenth century work on the History of India clearly establishes the Marathas as the native people of Western Dakkan who rose to power under the genius of two medieval rulers of the Deccan, Mallik Ambar who effectively armed the Marathas and ChhatrapatiShivaji who effectively used this mobilisation to establish a small compact state, the Maharashtra Swarajya in the middle half of the seventeenth century. This kingdom situated firmly in the Deccan plateau and the Konkan region in North-Western Maharashtra grew southwards and became the major opponent to all Indo-Islamic powers ranging from the local Deccan Sultanates and the invading Mughals who engulfed the Sultanates one by one creating a new province of Mughal Deccan. -

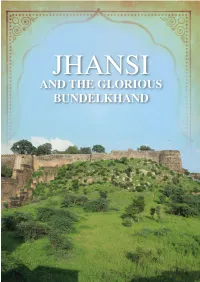

Glimpses of Jhansi's History Jhansi Through the Ages Newalkars of Jhansi What Really Happened in Jhansi in 1857?

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Glimpses of Jhansi's History Jhansi Through The Ages Newalkars of Jhansi What Really Happened in Jhansi in 1857? Attractions in and around Jhansi Jhansi Fort Rani Mahal Ganesh Mandir Mahalakshmi Temple Gangadharrao Chhatri Star Fort Jokhan Bagh St Jude’s Shrine Jhansi Cantonment Cemetery Jhansi Railway Station Orchha I N T R O D U C T I O N Jhansi is one of the most vibrant cities of Uttar Pradesh today. But the city is also steeped in history. The city of Rani Laxmibai - the brave queen who led her forces against the British in 1857 and the region around it, are dotted with monuments that go back more than 1500 years! While thousands of tourists visit Jhansi each year, many miss the layered past of the city. In fact, few who visit the famous Jhansi Fort each year, even know that it is in its historic Ganesh Mandir that Rani Laxmibai got married. Or that there is also a ‘second’ Fort hidden within the Jhansi cantonment, where the revolt of 1857 first began in the city. G L I M P S E S O F J H A N S I ’ S H I S T O R Y JHANSI THROUGH THE AGES Jhansi, the historic town and major tourist draw in Uttar Pradesh, is known today largely because of its famous 19th-century Queen, Rani Laxmibai, and the fearless role she played during the Revolt of 1857. There are also numerous monuments that dot Jhansi, remnants of the Bundelas and Marathas that ruled here from the 17th to the 19th centuries.