CHAPTER 3 CHILD BRIDE and WIFE for a Hinju, Maniage Is A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

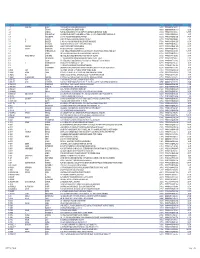

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A SPRAKASH REDDY 25 A D REGIMENT C/O 56 APO AMBALA CANTT 133001 0000IN30047642435822 22.50 2 A THYAGRAJ 19 JAYA CHEDANAGAR CHEMBUR MUMBAI 400089 0000000000VQA0017773 135.00 3 A SRINIVAS FLAT NO 305 BUILDING NO 30 VSNL STAFF QTRS OSHIWARA JOGESHWARI MUMBAI 400102 0000IN30047641828243 1,800.00 4 A PURUSHOTHAM C/O SREE KRISHNA MURTY & SON MEDICAL STORES 9 10 32 D S TEMPLE STREET WARANGAL AP 506002 0000IN30102220028476 90.00 5 A VASUNDHARA 29-19-70 II FLR DORNAKAL ROAD VIJAYAWADA 520002 0000000000VQA0034395 405.00 6 A H SRINIVAS H NO 2-220, NEAR S B H, MADHURANAGAR, KAKINADA, 533004 0000IN30226910944446 112.50 7 A R BASHEER D. NO. 10-24-1038 JUMMA MASJID ROAD, BUNDER MANGALORE 575001 0000000000VQA0032687 135.00 8 A NATARAJAN ANUGRAHA 9 SUBADRAL STREET TRIPLICANE CHENNAI 600005 0000000000VQA0042317 135.00 9 A GAYATHRI BHASKARAAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041978 135.00 10 A VATSALA BHASKARAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041977 135.00 11 A DHEENADAYALAN 14 AND 15 BALASUBRAMANI STREET GAJAVINAYAGA CITY, VENKATAPURAM CHENNAI, TAMILNADU 600053 0000IN30154914678295 1,350.00 12 A AYINAN NO 34 JEEVANANDAM STREET VINAYAKAPURAM AMBATTUR CHENNAI 600053 0000000000VQA0042517 135.00 13 A RAJASHANMUGA SUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST AND TK THANJAVUR 614625 0000IN30177414782892 180.00 14 A PALANICHAMY 1 / 28B ANNA COLONY KONAR CHATRAM MALLIYAMPATTU POST TRICHY 620102 0000IN30108022454737 112.50 15 A Vasanthi W/o G -

Maharashtra State Boatd of Sec & H.Sec Education Pune

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE PAGE : 1 College wise performance ofFresh Regular candidates for HSC 2021 Candidates passed College No. Name of the collegeStream Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 01.01.001 Z.P.BOYS JUNIOR COLLEGE, AKOLA SCIENCE 66 66 66 0 0 0 66 100.00 27050803901 ARTS 14 14 7 7 0 0 14 100.00 COMMERCE 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 100.00 TOTAL 81 81 74 7 0 0 81 100.00 01.01.002 GOVERNMENT TECHNICAL COLLEGE, AKOLA SCIENCE 17 17 16 1 0 0 17 100.00 27050117183 TOTAL 17 17 16 1 0 0 17 100.00 01.01.003 R.L.T. SCIENCE COLLEGE, AKOLA CIVIL LINE SCIENCE 544 544 543 1 0 0 544 100.00 27050117184 TOTAL 544 544 543 1 0 0 544 100.00 01.01.004 SHRI.SHIVAJI ARTS COMMERCE & SCIENCE SCIENCE 238 238 238 0 0 0 238 100.00 27050117186 COLLEGE,AKOLA ARTS 160 160 60 100 0 0 160 100.00 COMMERCE 183 183 110 73 0 0 183 100.00 TOTAL 581 581 408 173 0 0 581 100.00 01.01.005 SMT L.R.T. COMMERCE COLLEGE , AKOLA COMMERCE 761 761 748 12 1 0 761 100.00 27050117187 TOTAL 761 761 748 12 1 0 761 100.00 01.01.006 SITABAI ARTS COLLEGE, AKOLA CIVIL LINE ROAD SCIENCE 7 7 7 0 0 0 7 100.00 27050119003 ARTS 111 111 47 61 3 0 111 100.00 COMMERCE 105 105 97 8 0 0 105 100.00 MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE PAGE : 2 College wise performance ofFresh Regular candidates for HSC 2021 Candidates passed College No. -

India's Missed Opportunity: Bajirao and Chhatrapati

India's Missed Opportunity: Bajirao and Chhatrapati By Gautam Pingle, Published: 25th December 2015 06:00 AM http://www.newindianexpress.com/columns/Indias-Missed-Opportunity-Bajirao-and- Chhatrapati/2015/12/25/article3194499.ece The film Bajirao Mastani has brought attention to a critical phase in Indian history. The record — not so much the film script — is relatively clear and raises important issues that determined the course of governance in India in the 18th century and beyond. First, the scene. The Mughal Empire has been tottering since Shah Jahan’s time, for it had no vision for the country and people and was bankrupt. Shah Jahan and his son Aurangzeb complained they were not able to collect even one-tenth of the agricultural taxes they levied (50 per cent of the crop) on the population. As a result, they were unable to pay their officials. This meant that the Mughal elite had to be endlessly turned over as one set of officials and generals were given the jagirs-in-lieu-of-salaries of their predecessors (whose wealth was seized by the Emperor). The elite became carnivorous, rapacious and rebellious accelerating the dissolution of the state. Yet, the Mughal Empire had enough strength and need to indulge in a land grab and loot policy. Second, the Deccan Sultanates were enormously rich because they had a tolerable taxation system which encouraged local agriculture and commerce. The Sultans ruled a Hindu population through a combined Hindu rural and urban elite and a Muslim armed force. This had established a general ‘peace’ between the Muslim rulers and the Hindu population. -

New Microsoft Office Excel Worksheet.Xlsx

DETAILS OF UNPAID/UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND FOR fy‐2013‐14 AS ON 1ST AUGUST,2017 Prpoposed Amount Date of TransferrTransferr TransferTransfer to Investor First Name Investor Middle Name Investor Last Name Address Country State District Pin Code Folio No. DP Id‐Client Id Account Number Investment Type ed IEPF NITIN JAIN 1003 DLF PHASE‐IV GURGAON HARYANA INDIA HARYANA GURGAON 122001 C12016400‐12016400‐00057150 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 2400.00 15‐SEP‐2021 KAMAL NARAYAN SONI DOOR NO.11‐10‐14, BONDADA VEEDHI, NEAR MAZID, VIZIANAGARAM. ANDHRA PRADESH INDIA KERALA TRIVANDRUM 695010 C12013500‐12013500‐00012773 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 6.00 15‐SEP‐2021 SAPAN NEMA SAPAN NEMA KHARAKUWA SHUJALPUR CITY SHUJALPUR M.P INDIA KARNATAKA BANGALORE 560001 C12031600‐12031600‐00126133 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 30.00 15‐SEP‐2021 SRINIVAS H KULKARNI NO: 528/2 BHAGYANAGAR BLOCK‐2,KOPPALA RAICHUR KARNATAKA INDIA KARNATAKA BANGALORE 560001 C12032800‐12032800‐00135284 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 3.60 15‐SEP‐2021 RADHEY SHYAM PANDEY S/O RAM NARAYAN PANDEY NASOORUDDINPUR SATHIAON, SADAR TEHSIL AZAMGARH UP INDIA UTTAR PRADESH GORAKHPUR 273001 C13025900‐13025900‐00822209 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 24.00 15‐SEP‐2021 VASUNDHARA SHARMA K.G.TILES FACTORY KE PICHHE CHOPRA KATLA RANI BAZAR BIKANER RAJASTHAN INDIA RAJASTHAN AJMER 305001 C12017701‐12017701‐00148886 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 6.00 15‐SEP‐2021 SANJAY BAJPAI H No.‐ 747 LUCKNOW ROAD HARDOI U.P. INDIA UTTAR PRADESH GORAKHPUR 273001 C12032700‐12032700‐00104476 -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

Chapter 5 - Architectural and Urban Patronage

CHAPTER 5 - ARCHITECTURAL AND URBAN PATRONAGE In 1779 CE Ahilyābāī Hoḷkar sent a letter to Gopikābāī Peśvā, grandmother of the then Peśvā, Savāī Mādhavrāv and the wife of Nānāsāheb Peśvā. Some years before, Gopikābāī, who was staying at Nāśik, had constructed a kuṅda and ghāṭ on the Godāvarī River known respectively as Rāmkuṅda and Rāmghāṭ. Ahilyābāī wrote to Gopikābāī requesting for permission to repair and rebuild the same in a more artistic manner. Gopikābāī flatly refused any such permission saying that the kuṅda and ghāṭ were meant to preserve her memories which she did not want to be destroyed (Sathe, 2013, p. 143). Ahilyābāī retaliated by not sending the sarees that Gopikābāī had requested from Maheshwar. It was an act of what Bourdieu has termed as ‘symbolic violence’, a strategy employed by those having legitimacy in the social field to maintain their positions from any competition. Clearly, Gopikābāī saw Ahilyābāī’s intervention as a threat to her authority. This apparently simple event shows the acute awareness that patrons had, of the power of architecture in consolidating their social positions. They used architecture consciously to further their social and political aims. What purposes did the construction projects serve beyond the mere function? How were buildings used by the agents to assert authority and consolidate social positions? Can we trace any thematic continuity between the patronage of preceding centuries and the eighteenth century? This chapter attempts to answer such questions by focusing on patronage and matronage in the study area. Patronage and its relationship with architecture has been an important concern for a number of years in Historical studies. -

THE Tl1ird ENGLISH EMBASSY to POON~

THE Tl1IRD ENGLISH EMBASSY TO POON~ COMPRISING MOSTYN'S DIARY September, 1772-February, 1774 AND MOSTYN'S LETTERS February-177 4-Novembec- ~~:;, EDITED BY ]. H. GENSE, S. ]., PIL D. D. R. BANAJI, M. A., LL. B. BOMBAY: D. B. TARAPOREV ALA SONS & CO. " Treasure House of Books" HORNBY ROAD, FORT· COPYRIGHT l934'. 9 3 2 5.9 .. I I r\ l . 111 f, ,.! I ~rj . L.1, I \! ., ~ • I • ,. "' ' t.,. \' ~ • • ,_' Printed by 1L N. Kulkarni at the Katnatak Printing Pr6SS, "Karnatak House," Chira Bazar, Bombay 2, and Published by Jal H. D. Taraporevala, for D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Hornby Road, Fort, Bombay. PREFACE It is well known that for a hundred and fifty years after the foundation of the East India Company their representatives in ·India merely confined their activities to trade, and did not con· cern themselves with the game of building an empire in the East. But after the middle of the 18th century, a severe war broke out in Europe between England and France, now known as the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), which soon affected all the colonies and trading centres which the two nations already possessed in various parts of the globe. In the end Britain came out victorious, having scored brilliant successes both in India and America. The British triumph in India was chiefly due to Clive's masterly strategy on the historic battlefields in the Presidencies of Madras and Bengal. It should be remembered in this connection that there was then not one common or supreme authority or control over the three British establishments or Presidencies of Bengal, Madras and Bombay. -

CHAPTER 5 WIDOWHOOD and SATI One Unavoidable and Important

CHAPTER 5 WIDOWHOOD AND SATI One unavoidable and important consequence of child-inan iages and the practice of polygamy w as a \ iin’s premature widowhood. During the period under study, there was not a single house that did not had a /vidow. Pause, one of the noblemen, had at one time 57 widows (Bodhya which meant widows whose heads A’ere tonsured) in the household A widow's life became a cruel curse, the moment her husband died. Till her husband was alive, she was espected and if she had sons, she was revered for hei' motherhood. Although the deatli of tiie husband, was not ler fault, she was considered inauspicious, repellent, a creature to be avoided at every nook and comer. Most of he time, she was a child-widow, and therefore, unable to understand the implications of her widowhood. Nana hadnavis niiirried 9 wives for a inyle heir, he had none. Wlien he died, two wives survived him. One died 14 Jays after Nana’s death. The other, Jiubai was very beautiful and only 9 years old. She died at the age of 66 r'ears in 1775 A.D. Peshwa Nanasaheb man'ied Radhabai, daugliter of Savkar Wakhare, 6 months before he died, Radhabai vas 9 years old and many criticised Nanasaheb for being mentally derailed when he man ied Radhabai. Whatever lie reasons for this marriage, he was sui-vived by 2 widows In 1800 A.D., Sardai' Parshurarnbhau Patwardlian, one of the Peshwa generals, had a daughter , whose Msband died within few months of her marriage. -

History of Modern Maharashtra (1818-1920)

1 1 MAHARASHTRA ON – THE EVE OF BRITISH CONQUEST UNIT STRUCTURE 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Political conditions before the British conquest 1.3 Economic Conditions in Maharashtra before the British Conquest. 1.4 Social Conditions before the British Conquest. 1.5 Summary 1.6 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES : 1 To understand Political conditions before the British Conquest. 2 To know armed resistance to the British occupation. 3 To evaluate Economic conditions before British Conquest. 4 To analyse Social conditions before the British Conquest. 5 To examine Cultural conditions before the British Conquest. 1.1 INTRODUCTION : With the discovery of the Sea-routes in the 15th Century the Europeans discovered Sea route to reach the east. The Portuguese, Dutch, French and the English came to India to promote trade and commerce. The English who established the East-India Co. in 1600, gradually consolidated their hold in different parts of India. They had very capable men like Sir. Thomas Roe, Colonel Close, General Smith, Elphinstone, Grant Duff etc . The English shrewdly exploited the disunity among the Indian rulers. They were very diplomatic in their approach. Due to their far sighted policies, the English were able to expand and consolidate their rule in Maharashtra. 2 The Company’s government had trapped most of the Maratha rulers in Subsidiary Alliances and fought three important wars with Marathas over a period of 43 years (1775 -1818). 1.2 POLITICAL CONDITIONS BEFORE THE BRITISH CONQUEST : The Company’s Directors sent Lord Wellesley as the Governor- General of the Company’s territories in India, in 1798.