CHAPTER 5 WIDOWHOOD and SATI One Unavoidable and Important

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

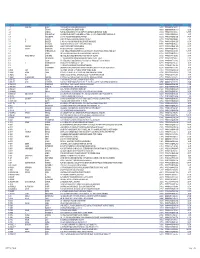

Sr. No. College Name University Name Taluka District JD Region

Non-Aided College List Sr. College Name University Name Taluka District JD Region Correspondence College No. Address Type 1 Shri. KGM Newaskar Sarvajanik Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Pandit neheru Hindi Non-Aided Trust's K.G. College of Arts & Pune University, ar ar vidalaya campus,Near Commerece, Ahmednagar Pune LIC office,Kings Road Ahmednagrcampus,Near LIC office,Kings 2 Masumiya College of Education Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune wable Non-Aided Pune University, ar ar colony,Mukundnagar,Ah Pune mednagar.414001 3 Janata Arts & Science Collge Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune A/P:- Ruichhattishi ,Tal:- Non-Aided Pune University, ar ar Nagar, Dist;- Pune Ahmednagarpin;-414002 4 Gramin Vikas Shikshan Sanstha,Sant Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune At Post Akolner Tal Non-Aided Dasganu Arts, Commerce and Science Pune University, ar ar Nagar Dist Ahmednagar College,Akolenagar, Ahmednagar Pune 414005 5 Dr.N.J.Paulbudhe Arts, Commerce & Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune shaneshwar nagarvasant Non-Aided Science Women`s College, Pune University, ar ar tekadi savedi Ahmednagar Pune 6 Xavier Institute of Natural Resource Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Behind Market Yard, Non-Aided Management, Ahmednagar Pune University, ar ar Social Centre, Pune Ahmednagar. 7 Shivajirao Kardile Arts, Commerce & Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Jambjamb Non-Aided Science College, Jamb Kaudagav, Pune University, ar ar Ahmednagar-414002 Pune 8 A.J.M.V.P.S., Institute Of Hotel Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag -

Maharaja Serfoji Ii -The Famous Thanjavur Maratha King

Vol. 3 No. 3 January 2016 ISSN: 2321 – 788X MAHARAJA SERFOJI II -THE FAMOUS THANJAVUR MARATHA KING Dr. S. Vanajakumari Associate Professor, Department of History, Sri Meenakshi Govt. College (W), Madurai- 625 002 Abstract The place of Thanjavur in Tamilnadu (South India) has a long past history, fertile region and capital of many kingdoms. Thanjavur was a part of the kingdom of the Sangam Cholas. Later Thanjavur was ruled by the Kalabhras, the Pallavas and the Imperial Cholas. Then it was for a short period under the rule of the Pandyas and Vijayanagar Kings who appointed Sevappa Nayak as a viceroy of Thanjavur. Keywords: Thanjavur, Sangam, Kalabhras, Pandyas, Vijayanagar, Pallavas, Marathas, Chattrapathy Shivaji Establishment of Marathas power in Thanjavur Sevappa Nayak (1532-1560) was the founder of Thanjavur Nayak dynasty.1 Vijayaraghava (1634-1674) the last king of this dynasty, lost his life in a battle with Chokkanatha Nayak of Madurai in the year 1662. The Madurai Nayak appointed Alagiri, as the Governor of Thanjavur. This was followed by a long civil war in the Thanjavur kingdom. Alagiri wanted to rule independently and it restrained the relationship between Alagiri and Chokkanatha Nayak. Sengamaladas was the infant son of Vijayaraghava. Venkanna the Rayasam of Vijayaragava desired to make Sengamaladas as the Nayak of Thanjavur and sought the help of Bijapur Sultan who send Ekoji alias Venkogi to capture Thanjavur. He defeated Alagiri and crowned Sengamaladas. But, Venkanna did not get any benefit from Sengamaladas. So he induced Ekoji to usurp the power and got victory. Thus, in 1676 Ekoji established Maratha rule in the Tamil country. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Ahilyabai Holkar Author: Sandhya Taksale Illustrator: Priyankar Gupta a Chance Encounter (1733)

Ahilyabai Holkar Author: Sandhya Taksale Illustrator: Priyankar Gupta A chance encounter (1733) “Look at these beautiful horses and elephants! Who brought them here?” squealed Ahilya. Reluctantly, she tore her eyes away from the beautiful animals – it would get dark soon! She hurried inside the temple and lit a lamp. Ahilya closed her eyes and bowed in prayer. 2/23 Little did she know that she was being watched by Malharrao. He was the brave and mighty Subedar, a senior Maratha noble, of the Malwa province. On his way to Pune, he had camped in the village of Chaundi in Maharashtra. It was his horses and elephants that Ahilya had admired. “She has something special about her. She would make a good bride for my son, Khanderao,” Malharrao thought. In those days, marriages happened early. 3/23 Off to Indore Ahilya was the daughter of the village head, Mankoji Shinde. She hailed from a shepherd family. In those days, girls were not sent to school. Society considered the role of women as only managing the household and taking care of the family; educating a girl was not given importance. But Ahilya’s father thought differently and taught her to read and write. After Ahilya and Khanderao were married, Ahilya went to Indore, which was in the Malwa province, as the Holkar family’s daughter-in- law. The rest is history. She was destined to become a queen! 4/23 Who was Ahilyabai? Three hundred years ago, Maharani Ahilyabai ruled the Maratha-led Malwa kingdom for 28 years (1767-1795 A.D). -

Maharashtra State Boatd of Sec & H.Sec Education Pune

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 1 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2020 Division : MUMBAI Candidates passed School No. Name of the School Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 16.01.001 SAKHARAM SHETH VIDYALAYA, KALYAN,THANE 185 185 22 57 52 29 160 86.48 27210508002 16.01.002 VIDYANIKETAN,PAL PYUJO MANPADA, DOMBIVLI-E, THANE 226 226 198 28 0 0 226 100.00 27210507603 16.01.003 ST.TERESA CONVENT 175 175 132 41 2 0 175 100.00 27210507403 H.SCHOOL,KOLEGAON,DOMBIVLI,THANE 16.01.004 VIVIDLAXI VIDYA, GOLAVALI, 46 46 2 7 13 11 33 71.73 27210508504 DOMBIVLI-E,KALYAN,THANE 16.01.005 SHANKESHWAR MADHYAMIK VID.DOMBIVALI,KALYAN, THANE 33 33 11 11 11 0 33 100.00 27210507115 16.01.006 RAYATE VIBHAG HIGH SCHOOL, RAYATE, KALYAN, THANE 151 151 37 60 36 10 143 94.70 27210501802 16.01.007 SHRI SAI KRUPA LATE.M.S.PISAL VID.JAMBHUL,KULGAON 30 30 12 9 2 6 29 96.66 27210504702 16.01.008 MARALESHWAR VIDYALAYA, MHARAL, KALYAN, DIST.THANE 152 152 56 48 39 4 147 96.71 27210506307 16.01.009 JAGRUTI VIDYALAYA, DAHAGOAN VAVHOLI,KALYAN,THANE 68 68 20 26 20 1 67 98.52 27210500502 16.01.010 MADHYAMIK VIDYALAYA, KUNDE MAMNOLI, KALYAN, THANE 53 53 14 29 9 1 53 100.00 27210505802 16.01.011 SMT.G.L.BELKADE MADHYA.VIDYALAYA,KHADAVALI,THANE 37 36 2 9 13 5 29 80.55 27210503705 16.01.012 GANGA GORJESHWER VIDYA MANDIR, FALEGAON, KALYAN 45 45 12 14 16 3 45 100.00 27210503403 16.01.013 KAKADPADA VIBHAG VIDYALAYA, VEHALE, KALYAN, THANE 50 50 17 13 -

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A SPRAKASH REDDY 25 A D REGIMENT C/O 56 APO AMBALA CANTT 133001 0000IN30047642435822 22.50 2 A THYAGRAJ 19 JAYA CHEDANAGAR CHEMBUR MUMBAI 400089 0000000000VQA0017773 135.00 3 A SRINIVAS FLAT NO 305 BUILDING NO 30 VSNL STAFF QTRS OSHIWARA JOGESHWARI MUMBAI 400102 0000IN30047641828243 1,800.00 4 A PURUSHOTHAM C/O SREE KRISHNA MURTY & SON MEDICAL STORES 9 10 32 D S TEMPLE STREET WARANGAL AP 506002 0000IN30102220028476 90.00 5 A VASUNDHARA 29-19-70 II FLR DORNAKAL ROAD VIJAYAWADA 520002 0000000000VQA0034395 405.00 6 A H SRINIVAS H NO 2-220, NEAR S B H, MADHURANAGAR, KAKINADA, 533004 0000IN30226910944446 112.50 7 A R BASHEER D. NO. 10-24-1038 JUMMA MASJID ROAD, BUNDER MANGALORE 575001 0000000000VQA0032687 135.00 8 A NATARAJAN ANUGRAHA 9 SUBADRAL STREET TRIPLICANE CHENNAI 600005 0000000000VQA0042317 135.00 9 A GAYATHRI BHASKARAAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041978 135.00 10 A VATSALA BHASKARAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041977 135.00 11 A DHEENADAYALAN 14 AND 15 BALASUBRAMANI STREET GAJAVINAYAGA CITY, VENKATAPURAM CHENNAI, TAMILNADU 600053 0000IN30154914678295 1,350.00 12 A AYINAN NO 34 JEEVANANDAM STREET VINAYAKAPURAM AMBATTUR CHENNAI 600053 0000000000VQA0042517 135.00 13 A RAJASHANMUGA SUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST AND TK THANJAVUR 614625 0000IN30177414782892 180.00 14 A PALANICHAMY 1 / 28B ANNA COLONY KONAR CHATRAM MALLIYAMPATTU POST TRICHY 620102 0000IN30108022454737 112.50 15 A Vasanthi W/o G -

Commitment and Conquest: the Case of British Rule in India

The University of Adelaide School of Economics Research Paper No. 2009-24 Commitment and Conquest: The Case of British Rule in India Mandar P. Oak and Anand Swamy The University of Adelaide, School of Economics Working Paper Series no. 0083 (2009 - 24) Commitment and Conquest: The Case of British Rule in India Mandar P. Oak School of Economics University of Adelaide Adelaide AUSTRALIA Anand Swamy Dept of Economics Williams College Williamstown MA, USA Preliminary draft. Do not quote without premission. July 24, 2009 Abstract Contemporary historians usually attribute the East India Company’s military success in India to its military strength. In contrast, we argue that, on its own, military strength was a mixed blessing: it could have led to the formation of coalitions against the Company. This did not happen because the Company’scommitments to Indian regimes were more credible than their commitments to each other. In this sense, commitment was the key to conquest. 1 1 Introduction There is a huge and sophisticated literature on why the East India Company, a trading enterprise, was able to conquer India. The dominant view among modern historians foregrounds the Company’ssuperior military power, based on better technology and access to capital, and support from the British state.1 An- other group of historians, while acknowledging the Company’smilitary strength, also emphasize the myopia of Indian regimes, arguing that they failed to recog- nize that their disunity would pave the way for the Company’s ascendance, via serial conquest.2 A variant of this view (Stein 2001, p.209) emphasizes the Company’sorganizational structure, arguing that Indian regimes were "lulled" into a false sense of security because they were aware that authorities in London (with oversight over the Company in India) were conservative, and opposed to risky warfare. -

FALL of MARATHAS, 1798–1818 A.D. the Position of Marathas in 1798 A.D

M.A. (HISTORY) PART–II PAPER–II : GROUP C, OPTION (i) HISTORY OF INDIA (1772–1818 A.D.) LESSON NO. 2.4 AUTHOR : PROF. HARI RAM GUPTA FALL OF MARATHAS, 1798–1818 A.D. The Position of Marathas in 1798 A.D. The Marathas had been split up into a loose confederacy. At the head of the Maratha empire was Raja of Sitara. His power had been seized by the Peshwa Baji Rao II was the Peshwa at this time. He became Peshwa at the young age of twenty one in December, 1776 A.D. He had the support of Nana Pharnvis who had secured approval of Bhonsle, Holkar and Sindhia. He was destined to be the last Peshwa. He loved power without possessing necessary courage to retain it. He was enamoured of authority, but was too lazy to exercise it. He enjoyed the company of low and mean companions who praised him to the skies. He was extremely cunning, vindictive and his sense of revenge. His fondness for wine and women knew no limits. Such is the character sketch drawn by his contemporary Elphinstone. Baji Rao I was a weak man and the real power was exercised by Nana Pharnvis, Prime Minister. Though Nana was a very capable ruler and statesman, yet about the close of his life he had lost that ability. Unfortunately, the Peshwa also did not give him full support. Daulat Rao Sindhia was anxious to occupy Nana's position. He lent a force under a French Commander to Poona in December, 1797 A.D. Nana Pharnvis was defeated and imprisoned in the fort of Ahmadnagar. -

Lesson 3 the Marquess of Wellesley (1798-1805)

LESSON 3 THE MARQUESS OF WELLESLEY (1798-1805) Learning Objectives Students will come to understand 1. The political condition of India at the time of the arrival of Lord Wellesley 2. The Meaning of Subsidiary System 3. Merits and defects of the Subsidiary System 4. The Indian states that come under this system 5. Fourth Mysore War and the final fall of Tipu Sultan 6. War with the Marathas. 7. Estimate of Lord Wellesley The appointment of Richard Colley Wellesley as GovernorGeneral marks an epoch in the history of British India. He was a great imperialist and called himself ‘a Bengal tiger’. Wellesley came to India with a determination to launch a forward policy in order to make ‘the British Empire in India’ into ‘the British Empire of India’. The system that he adopted to achieve his object is known as the ‘Subsidiary Alliance’ Political Condition of India at the time of Wellesley’s Arrival In the north-western India, the danger of Zaman Shah’s aggression posed a serious threat to the British power in India. In the north and central India, the Marathas remained a formidable political power. The Nizam of Hyderabad employed the Frenchmen to train his LESSON 3 THE MARQUESS OF WELLESLEY (1798-1805) Learning Objectives Students will come to understand 1. The political condition of India at the time of the arrival of Lord Wellesley 2. The Meaning of Subsidiary System 3. Merits and defects of the Subsidiary System 4. The Indian states that come under this system 5. Fourth Mysore War and the final fall of Tipu Sultan 6. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS,