Travelling Through Caste

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lord and His Land

Orissa Review * June - 2006 The Lord and His Land Dr. Nishakar Panda He is the Lord of Lords. He is Jagannath. He century. In Rajabhoga section of Madala Panji, is Omniscient, Omnipotent and Omnipresent. Lord Jagannatha has been described as "the He is the only cult, he is the only religion, he king of the kingdom of Orissa", "the master is the sole sect. All sects, all 'isms', all beliefs or the lord of the land of Orissa" and "the god and all religions have mingled in his eternal of Orissa". Various other scriptures and oblivion. He is Lord Jagannatha. And for narrative poems composed by renowned poets Orissa and teeming millions of Oriyas are replete with such descriptions where He is the nerve centre. The Jagannatha has been described as the institution of Jaganatha sole king of Orissa. influences every aspect of the life in Orissa. All spheres of Basically a Hindu our activities, political, deity, Lord Jagannatha had social, cultural, religious and symbolized the empire of economic are inextricably Orissa, a collection of blended with Lord heterogeneous forces and Jagannatha. factors, the individual or the dynasty of the monarch being A Political Prodigy : the binding force. Thus Lord Lord Jaganatha is always Jagannatha had become the and for all practical proposes national deity (Rastra Devata) deemed to be the supreme besides being a strong and monarch of the universe and the vivacious force for integrating Kings of Orissa are regarded as His the Orissan empire. But when the representatives. In yesteryears when Orissa empire collapsed, Lord Jagannatha had been was sovereign, the kings of the sovereign state seen symbolizing a seemingly secular force of had to seek the favour of Lord Jaganatha for the Oriya nationalism. -

Padayatras Done in 2019

ISKCON - The International Society for Krishna Consciousness (Founder Acharya His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada) Newsletter 2020 PLEASE POST IN YOUR TEMPLE PADAYATRAS DONE IN 2019 INDIA All-India (since 1986) All-Telangana All- Maharashtra All-Uttar Pradesh All-Andhra Pradesh All-Gujarat Maharashtra : • Pune to Pandharpur • Jalgaon • Amravati • Dhamangaon • Latur • Sangli • Nandurbar • Akola • Alibag • Kasegaon to Pandharpur Other states • Jamshedpur (Jarkhand) • Ahmedabad (Gujarat) • Baroda to Dakor (Gujarat) • Bhubaneswar (Orissa) • Noida to Vrindavana (U.P.) Note: Some of these temples did several One Day Padayatras, special or longer walks EUROPE Hungary Slovenia UK Czech Republic NORTH Canada AMERICA SOUTH Guyana AMERICA Trinidad REST OF La Réunion THE WORLD Mauritius South Africa EDITORIAL TABLE OF CONTENTS By Lokanath Swami Editorial 1 by Lokanath Swami Dear readers, First all-Vaisnavi padayatra 3 Are we now witnessing another padayatra explosion, by Jayabhadra dasi as it happened in the nineties, the years preceding Srila All great acaryas went on Padayatra 5 Prabhupada›s Centennial celebrations? Padayatra is by Gaurangi dasi indeed expanding, particularly in India. Besides its two The Bull Star, busier than Bollywood Heroes 8 ongoing walks, the All-India Padayatra and the Andhra This newsletter is dedicated to by Dr Sahadeva dasa Pradesh/Telangana Padayatra and the regular smaller ISKCON Founder-Acarya, padayatras, two new teams have recently taken to the road His Divine Grace A.C.Bhaktivedanta Oxen and cows are special animals 10 with oxcarts, in Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh. Their Swami Prabhupada by Gaurangi dasi goal? To keep walking, chanting and dancing to every town, village around these states in order to fulfil Lord US 1989 Inauguration of Padayatra America in San Francisco Why did Srila Prabhupada personally One day Padayatra 11 Caitanya›s prophecy and desire that the holy names reach instruct Lokanath Swami to organise a by Muralimohan dasa Day formula adopted in the rest of the world. -

“In the Association of Pure Devotees, Discussion of the Pastimes and Activities of the Supreme Personality of Godhead Is Ve

“IN THE ASSOCIATION OF PURE DEVOTEES, DISCUSSION OF THE PASTIMES AND ACTIVITIES OF THE SUPREME PERSONALITY OF GODHEAD IS VERY PLEASING AND SATISFYING TO THE EAR AND THE HEART. BY CULTIVATING SUCH KNOWLEDGE ONE GRADUALLY BECOMES ADVANCED ON THE PATH OF LIBERATION, AND THEREAFTER HE IS FREED, AND HIS ATTRACTION BECOMES FIXED. THEN REAL DEVOTION AND DEVOTIONAL SERVICE BEGIN.” SRIMAD BHAGAVATAM 3.25.25 SRI VYASA-PUJA SRI Appearance day of our beloved THE MOST BLESSED EVENTTHE HIS HOLINESS KADAMBA KANANA SWAMI HOLINESS HIS VYASA PUJA 2020 HIS HOLINESS KADAMBA KANANA SWAMI SRI VYASA-PUJA APPEARANCE DAY OF OUR BELOVED SPIRITUAL MASTER HIS HOLINESS KADAMBA KANANA SWAMI APRIL 2020 CONTENTS JUST TRY TO LEARN TRUTH BY DISHA SIMHADRI .................... 42 APPROACHING TO SPIRITUAL DOYAL GOVINDA DASA .......... 43 MASTER ......................................1 DR FRANKA ENGEL .................. 44 SIGNIFICACE OF SRI VYASA ELISHA PATEL .......................... 45 PUJA............................................3 GAURA NARAYANA DASA ....... 46 STRONG INDIVIDUALS .............. 8 GITA GAMYA DEVI DASI .........47 GITA GOVINDA DEVI DASI ...... 49 OFFERINGS GITA LALASA DASI .................. 53 ACYUTA KESAVA DASA & ANAKULYA DEVI DASI................9 GODRUMA DASA ...................... 54 ADI GANGA DEVI DASI ............10 GOPALI DEVI DASI .................. 56 ADIKARTA DASA .......................12 GUNTIS LAN .............................57 ADRIENN MAKAINE PATAY.....13 GURUDASA .......................... .....58 ALPESH PATEL ..........................15 -

Lakshmi Against Untouchability: Puranic Texts and Caste in Odisha

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Lakshmi against Untouchability: Puranic Texts and Caste in Odisha RAJ KUMAR Raj Kumar ([email protected]) teaches at the Department of English, University of Delhi. Vol. 54, Issue No. 48, 07 Dec, 2019 The Lakshmi Purana as a literary text primarily raises issues relating to the religious rights of Dalit women in Odisha. Lakshmibrata kathas are stories that are recited while worshipping Lakshmi, the Goddess. Lakshmi, the Goddess of wealth, is now being worshipped all over India. But, the literary sources coming out in various Indian languages prove that the Lakshmibrata kathas originated mostly in the rice-producing states such as, West Bengal (WB), Bihar, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh (AP), Karnataka and Uttar Pradesh (UP). Bidyut Mohanty took nearly 20 years to prove this research hypothesis. His book, Lakshmi, the Rebel: Culture, Economy and Women’s Agency published by Har-Ananad, Delhi, 2019, is an attempt to study caste, culture, and gender, through myths. Taking the Lakshmibrata kathas as tools to investigate the various locations of gendered culture in India, the book connects between the past and the present and makes a bold statement about the degree of women empowerment in India. Mohanty, after critically analysing the Lakshmibrata kathas of various states Mohanty wrote, ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 “We have seen in many countries that political representation and economic opportunities which are indeed absolutely necessary for women’s empowerment have still proved to be inadequate in accomplishing women’s liberation in modern times. In this work, it has been argued that culture has to be an integral component in the composite perspective along with political and economic measures to bring about women’s liberation. -

Social Anthropology of Orissa: a Critique

International Journal of Cross-Cultural Studies Vol. 2 No. 1 (June, 2016) ISSN: 0975-1173 www.mukpublications.com Social Anthropology of Orissa: A Critique Nava Kishor Das Anthropological Survey of India India ABSTRACT Orissa is meeting place of three cultures, Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, and Munda and three ethno- linguistic sections. There are both indigenous and immigrant components of the Brahmans, Karna, who resemble like the Khatriyas, and others. The theory that Orissa did not have a viable Kshatriya varna has been critically considered by the historian -anthropologists. We will also see endogenous and exogenous processes of state formation. The Tribespeople had generally a two-tier structure of authority- village chief level and at the cluster of villages (pidha). Third tier of authority was raja in some places. Brahminism remained a major religion of Orissa throughout ages, though Jainism and Buddhism had their periods of ascendancy. There is evidence when Buddhism showed tendencies to merge into Hinduism, particularly into Saivism and Saktism. Buddhism did not completely die out, its elements entered into the Brahmanical sects. The historians see Hinduisation process intimately associated with the process of conversion, associated with the expansion of the Jagannatha cult, which co-existed with many traditions, and which led to building of Hindu temples in parts of tribal western Orissa. We notice the co-existence of Hinduisation/ peasantisation/ Kshatriyaisation/ Oriyaisation, all operating variously through colonisation. In Orissa, according to Kulke it was continuous process of ‘assimilation’ and partial integration. The tribe -Hindu caste intermingling is epitomised in the Jagannatha worship, which is today at the centre of Brahminic ritual and culture, even though the regional tradition of Orissa remaining tribal in origin. -

Blue Hill Book Review

OHRJ, Vol. XLVII, No. 2 BLUE HILL BOOK REVIEW “ Pranipatya Jagannatham, Sarva jina Vararchitam. Sarva Buddhamayam Siddhi, Vyapino Gaganopamam ” The book BLUE HILL written by Dr. Subas Pani & Published by Rupa & Co, New Delhi in 2004 is a unique Publication for its theme, rendering and the Universal deity Lord Jagannath. The subject matter revolves round the eclectic & syncretic culture of Jagannath Triad. The origin and evolution of Jagannath Consciousness in Puri is shrouded in mystery. Many scholars trace back the beginning of this religion to Vedic period. The antiquity of Puri as a centre of pilgrimage goes to 6th centaury B.C. to the days of Budhha as evident from Buddhist literature and Archeological reference. A Danta Dhatu of Lord Buddha was brought by one Thera Khema from Kusinara to Puri for worship from the funeral pyre of Buddha. Since then Puri was known as Dantapuri and was famous as a maritime trading metropolis. From that time onwards there was unprecedented acculturation and most of the known cults and creeds of Orissa & India mingled with the Jagannath Triad making the deity Lord of the Universe and rightly Dr. Pani has delved deep into the matter in his book. In fact Lord Jagannath epitomizes Buddism ,Jainism, Vaisnavism, Saivism, Shaktism and aboriginal Tribalism. Many Hymns of different sections grew up in volumes in oral & written traditions for the prayer and pacification of the all pervasive God since remote antiquity, which are still in continuity. The prayer of Vajrajani Buddhist Siddha Indrabhuti Pranipatya Jagannatham, Sarva jina Vararchitam.Sarva Budhamayam Siddhi, Vyapino Gaganopamam which is the invocatory verse of his famous book Gyana Siddhi ascribable to 8th Century is known to be the first historical written version of hymns to Jagannath and the prayer offerings of Santha Kabi Bhima Bhoi of Neo Buddism (Mahima Dharma) be regarded as the latest one of the Neo Orissan classic poetic diction. -

Purusottama Jagannath and Sri Chaitanya

Srimandira Purusottama Jagannatha and Sri Chaitanya l Pandit Nilambar Nanda The cosmic functions of creation, leads to the liberation of the immortal soul through union with the Lord. preservation and destruction constitute the sport of the Lord. He is the root of all Vedas, Upanishads, Bramhasutras, existence, the source and substance of all Mahabharata, Ramayan, Bhagabat and the creatures. He appears in different Gita have described this glory of the incarnations in different ages and displays Supreme Lord. In Srimad Bhagabatam, the his grandeur and divine majesty. He is called powers and skill of Lord Krishna together the Purusottama and Jagannatha, the Lord with His blissful sport have been described of the universe. exhaustively. By the sixteenth century, the entire country accepted this Bhagabata The supreme lord enacts his leelas in the mundane world, thereby enabling people school of religious philosophy as the to visualize Him and join His sport guideline. Bhagabata was accepted as the delightfully. Such spontaneous and cheerful hand book of religious tenets by all sections of people of the country. The essence of participation in His play is the secret of union with Him. When this is realized, action is Bhagabata Dharma was propagated by performed entirely for His sake. The ancient different religious teachers including Vedic seers realized this truth and therefore Sri Chaitanya Dev. The entire Sanskrit text performed all their individual and social was beautifully and lucidly translated by the duties as sacrifices on the altar of the Lord. greatest Oriya Vaishnava saint, Sri Jagannatha Dasa of Puri, who recited it daily This was known as yagna. -

Cultural History of Odisha 2017

2017 OBJECTIVE ULTURAL ISTORY OF DISHA IAS C H O www.historyofodisha.in | www.objectiveias.in Cultural History of Odisha 2017 2 Cultural History of Odisha 2017 Contents 1. Cultural Significane of Somovamsi Rule 2. Cultural Significane of Ganga Rule 3. Growth of Temple Architecture 4. Society During Bhaumakaras 5. Religious Life During Bhaumakaras 6. Society During Samovamsis and Ganga Period 7. Cult of Jagannatha 8. Sri Chaitanya Faith 9. Pancha Sakhas and Bhakti Movement 10. Social and Religious Like During Medieval Period 3 Cultural History of Odisha 2017 4 Cultural History of Odisha 2017 Cultural significance of the Somavamsi rule The cultural contribution of the Somavamsis is significant in many ways. The Somavamsis accepted the Varnashrama dharma i.e., traditional division of the society into four Varnas (Brahmana, Kshatriya, Vaishya and Sudra), and gave the highest status to the Brahmanas. By performing Vedic sacrifices and facilitating the migration of Brahrnanas from northern India through generous offer of land grants the Somavamsi rulers promoted the Brahminisation of the socio-religious life of Odisha as well as the assimilation of the north Indian Sanskritic culture into the Odishan culture. Women enjoyed respectable status in the Somavamsi society. Some of the Somavamsi queens performed important works like the construction of temples. The Queen Kolavatidevi, the mother of Udyota Keshari constructed the Brahmeswar temple at Bhubaneswar. Nevertheless, the status of women appears to have degenerated during this period. The Devadasi practice (the practice of dedicating maidens to the temples) and prostitution were prevalent during this period. The last Somavamsi king, Karnadeva married a dancing girl, named Karpurasri who was born of a Mahari or Devadasi. -

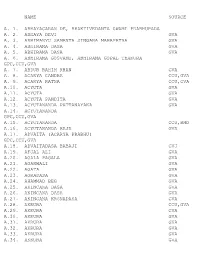

Gaud Vaish Ach.A-Y

NAME SOURCE A. 1. ABHAYACARAN DE, BHAKTIVEDANTA SWAMI PRABHUPADA A. 2. ABHAYA DEVI GVA A. 3. ABHIMANYU SAMANTA SINGARA MAHAPATRA GVA A. 4. ABHIRAMA DASA GVA A. 5. ABHIRAMA DASA GVA A. 6. ABHIRAMA GOSVAMI, ABHIRAMA GOPAL THAKURA GPC,CCU,GVA A. 7. ABDUR RAHIM KHAN GVA A. 8. ACARYA CANDRA CCU,GVA A. 9. ACARYA RATNA CCU,GVA A.10. ACYUTA GVA A.11. ACYUTA GVA A.12. ACYUTA PANDITA GVA A.13. ACYUTANANDA PATTANAYAKA GVA A.14. ACYUTANANDA GPC,CCU,GVA A.15. ACYUTANANDA CCU,BMO A.16. ACYUTANANDA RAJA GVA A.17. ADVAITA (ACARYA PRABHU) GPC,CCU,GVA A.18. ADVAITADASA BABAJI GVJ A.19. AFJAL ALI GVA A.20. AGALA PAGALA GVA A.21. AGARWALI GVA A.22. AGATA GVA A.23. AGRADASA GVA A.24. AHAMMAD BEG GVA A.25. AKINCANA DASA GVA A.26. AKINCANA DASA GVA A.27. AKINCANA KRSNADASA GVA A.28. AKRURA CCU,GVA A.29. AKRURA GVA A.30. AKRURA GVA A.31. AKRURA GVA A.32. AKRURA GVA A.33. AKRURA GVA A.34. AKRURA GVA A.35. AKBAR SHAH GVA A.36. ALAM GVA A.37. ALAOL SAHEB, SAIYAD GVA A.38. ALI MAHAMMAD GVA A.39. ALI RAJA GVA A.40. AMOGHA PANDITA BMO,CCU,GVA A.41. AMAN GVA A.42. AMULYADHANA RAYA BHATTA GVA A.43. ANANDA GVA A.44. ANANDACAND GVA A.45. ANANDACANDRA VIDYAVAGISA GVA A.46. ANANDA DASA GVA A.47. ANANDA DASA GVA A.48. ANANDA PURI GVA A.49. ANANDANANDA GVA A.50. ANANDARAMA LALA GVA A.51. ANANDI GVA A.52. -

Contributions of Panchasakha Literature to the Socio-Cultural Life of Odisha Dr

The Journey of Indian Languages: Perpectives on Culture and Society ISBN : 978-81-938282-5-0 Contributions of Panchasakha Literature to the Socio-Cultural Life of Odisha Dr. Rashmi Prava Panda Former Assistant Professor of History Currently Visiting Professor of History Calorx Teachers‟ University, Ahmedabad When there was an all-India phenomenon of Bhakti movement and Indian literature was fully saturated with the writings of mighty saints in all over India, Odisha shared this common platform and trends through a band of five fellow saint poets, generally known as Panchasakha. They were Balarama Dasa, Jagannath Dasa, Achyutananda Dasa, Ananta Dasa, and Jashovanta Dasa. They were all contemporaries of Sri Chaitanya. It is a common belief in Odisha that the epithet Panchasakha was used by Sri Chaitanya to refer to these saint poets. Their writings, enriched with philosophical ideas, religious themes, mythological episodes and socio-religious reforms, are famous as Panchasakha literatutre in the history of Odia literature and culture. Following the footstep of Adikavi (primordial or first poet) Sarala Dasa (who wrote Mahabharata in Odia language), Panchasakha wrote many sacred Hindu religious literature in vernacular language(odia) and made them available to the common people . They reflected in their writings that complex thoughts and abstract feelings of Hindu philosophy could not only be expressed in Sanskrit language but also in common people‘s language. Their literary works are very valuable in bringing the socio-religious reforms in Medieval Odisha as most of these writings protested against Brahminical supremacy, superstitious practices in Hinduism, rigid caste system and externality in spiritual life, etc. -

Role of Panchasakha in the Socio-Religious Life of the People of Odisha

Role of Panchasakha in the Socio-Religious life of the people of Odisha Akhay Mishra Odisha India Abstract Odisha displayed remarkable socio-religious harmony through the different times of her history. Right from the ancient period, Odisha, assumed to be a melting point of different religions and cultures. By the time when the Muslims started ruling over Odisha, Jainism, Buddhism, Sakti worship, Sun worship, Saivism and Vaishnavism all mingled together to influence the religious life of the people. This has been reflected in the social habits, food, dress and ornaments; and dance, music and festivals. A resume of such a socio-religious harmony was displayed in the period of Panchasakha. Odisha in the medieval period marks an era with the past in respect of the evolution of society. The Hindus gradually accommodated the newcomers viz., the Muslims and they became parts of Odishan society. The absence of racial conflicts exhibits the better social and religious understanding of the people belonging to all the segments of medieval Odisha. Introduction The bhakti movement influenced the whole country at different times, and had a definite impact not only on religious doctrines, rituals, values and popular beliefs, but on arts, culture and the state systems as well. The social protest and popular movement in medieval Orissa not only had a close bearing on the bhakti movement, it influenced almost the entire body of the contemporary society and culture. In this article, there is an attempt to discuss the role of Panchasakhas in Odia culture. Their influence on the ruling class of contemporary period has also been noticed. -

A REFLECTION of the HUMANISM and SOCIAL PROTEST in MEDIEVAL ODISHA Dr

© 2021 JETIR August 2021, Volume 8, Issue 8 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) BALARAM DASA’S WRITINGS: A REFLECTION OF THE HUMANISM AND SOCIAL PROTEST IN MEDIEVAL ODISHA Dr. Pareswar Sahoo Asst. Prof. in History S.B.Women’s Autonomous College, Cuttack, Odisha [email protected] ABSTRACT In the historical process medieval Odisha occupies a significant strand points. From the political history it is revealed that medieval Odisha is not much remarkable and far reaching in its approach and interpretation. It is because the existing practices against the social justice, liberty and freedom of the people. As a result this period has been marked by social and cultural protest movement in medieval Odisha. Some scholars of both national and colonial bent of thoughts like, A.K. Mishra, B.K.Mallik, H.S.Pattanaik, Jagabandhu Singh, have divergently argued the period as the Bhakti Movement in medieval Odisha. Particularly the colonial historians like W.W. Hunter, J.Beams, L.S.SO’ Malley have treated the period as the medieval renaissance and the nationalist historians have coined the period as socio-cultural protest movement. Balaram Dasa’s Laxmipuran occupies its momentum and treated as the first hand source material to reconstruct the social history of medieval Odisha. Besides its acute impact on the society and culture is the thrust area of study. This research paper has been developed keeping in view of some primary objectives. The prime objectives of this study are, how does the Laxmi Puran , the brain child of Balaram Dasa play an important role to bring reforms in the field of rights, social recognition, social dogmas , casteism, and position of women in medieval Odisha.