Milk Marketing Before and After Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Party Catering to Collect Autumn/Winter 2015/2016

PARTYPARTY CATERING CATERING TO COLLECTTO COLLECT AUTUMN/WINTERSPRING/SUMMER 2015/2016 2013 wwwww.athomecatering.co.ukw.athomecatering.co.uk CONTENTS BREAKFAST MENU (Minimum 10 covers) Contents Page PASTRY SELECTION £4.75 per person Miniature Croissant Miniature Pain au Raisin Breakfast menu 1 Miniature Pain au Chocolat Overstuffed sandwiches & sweet treats 2 - 3 CONTINENTAL £7.50 per person Freshly made salads 4 - 7 Miniature Croissant Miniature Pain au Raisin Fresh home made soups 8 Miniature Pain au Chocolat Baguette with Butter & Preserves Luxury soups, stocks & pasta sauces 9 Seasonal Fruits Cocktail/finger food 10 - 11 Freshly squeezed Orange Juice Starters & buffet dishes 12 - 13 EUROPEAN £9.50 per person Miniature Croissant Quiches & savoury tarts 14 Miniature Pain au Raisin Frittatas & savoury items 15 Miniature Pain au Chocolat Baguette & Focaccia with Butter & Preserves Chicken dishes 16 - 17 Serrano Ham with Caperberries & Olives Manchego cheese with Cherry Tomatoes & Cornichons Beef dishes 18 - 19 Muesli with Greek yogurt, Honey & Almonds Freshly squeezed Orange Juice Lamb dishes 20 - 21 Pork 22 AMERICAN £11.50 per person Miniature Croissant Duck & game 23 Miniature Pain au Raisin Miniature Pain au Chocolat Fish & seafood dishes 24 - 25 Lemon, Honey & Poppy seed Muffins Vegetarian dishes 26 Blueberry Muffins Poppy seed Bagels with Smoked Salmon, Cream cheese, Lemon & Chives Vegetable side dishes 27 Maple Cured bacon & Tomato rolls Fruit salad with Fromage Frais Whole puddings 28 - 29 Freshly squeezed Orange Juice Individual -

Port, Sherry, Sp~R~T5, Vermouth Ete Wines and Coolers Cakes, Buns and Pastr~Es Miscellaneous Pasta, Rice and Gra~Ns Preserves An

51241 ADULT DIETARY SURVEY BRAND CODE LIST Round 4: July 1987 Page Brands for Food Group Alcohol~c dr~nks Bl07 Beer. lager and c~der B 116 Port, sherry, sp~r~t5, vermouth ete B 113 Wines and coolers B94 Beverages B15 B~Bcuits B8 Bread and rolls B12 Breakfast cereals B29 cakes, buns and pastr~es B39 Cheese B46 Cheese d~shes B86 Confect~onery B46 Egg d~shes B47 Fat.s B61 F~sh and f~sh products B76 Fru~t B32 Meat and neat products B34 Milk and cream B126 Miscellaneous B79 Nuts Bl o.m brands B4 Pasta, rice and gra~ns B83 Preserves and sweet sauces B31 Pudd,ngs and fru~t p~es B120 Sauces. p~ckles and savoury spreads B98 Soft dr~nks. fru~t and vegetable Ju~ces B125 Soups B81 Sugars and artif~c~al sweeteners B65 vegetables B 106 Water B42 Yoghurt and ~ce cream 1 The follow~ng ~tems do not have brand names and should be coded 9999 ~n the 'brand cod~ng column' ~. Items wh~ch are sold loose, not pre-packed. Fresh pasta, sold loose unwrapped bread and rolls; unbranded bread and rolls Fresh cakes, buns and pastr~es, NOT pre-packed Fresh fru~t p1es and pudd1ngs, NOT pre-packed Cheese, NOT pre-packed Fresh egg dishes, and fresh cheese d1shes (ie not frozen), NOT pre-packed; includes fresh ~tems purchased from del~catessen counter Fresh meat and meat products, NOT pre-packed; ~ncludes fresh items purchased from del~catessen counter Fresh f1sh and f~sh products, NOT pre-packed Fish cakes, f1sh fingers and frozen fish SOLD LOOSE Nuts, sold loose, NOT pre-packed 1~. -

Cold: Hot: (V) Hummus with Feta & Piri Piri Chargrilled Chicken Wings Charred Flatbread Soldiers Spicy BBQ Glaze

Small Plates for grazing and sharing: £4.95 each or 3 for £14 Cold: Hot: (v) Hummus with Feta & Piri Piri Chargrilled Chicken Wings Charred flatbread soldiers Spicy BBQ glaze The Bridge ‘Hip Crisp’ and veggie Black pudding Bon bons platter Sautéed Chorizo, Grain mustard and apple Aioli, salsa and Chilli and BBQ dipping sauces mayonnaise (v) Marinated mixed olives Lamb Kofte Mint and lemon dressing Locally made Bread platter (v) Chargrilled Halloumi Oil and aged Balsamic vinegar Honey, chilli and lime dressing Starters Traditional ‘Cawl Cennin’ £6.50 Leek and potato soup with melted Caerphilly cheese topping (v) Breaded Pantysgawn Goat’s cheese £6.25 Breaded Pantysgawn goats cheese with mixed leaves and beetroot relish Taco Ty £7.50 Soft corn House taco of King prawns, chilli, ginger and spring onion, with salad, salsa & aioli. Chicken Liver and Welsh Penderyn Whisky pate £6.25 Crostini and apple chutney (vegan) Sweet potato and red lentil Dahl Croquettes £6.25 Chilli spiced mango sauce Pizzas – hand rolled Italian Dough base freshly baked in our wood fired oven The Welsh £12.50 Pulled slow cooked Lamb with leek and laverbread The Hawaiian £11.95 fresh baked ham and pineapple The Bridge Special £12.50 Rump steak, red onion and goat’s cheese (v) The Forager £10.95 Mixed mushrooms, spinach, red onion and balsamic glaze The Snowdon Dragon £11.50 Spicy Chorizo, Pepperoni, Padron peppers, red onion and chilli (v) Classic Margherita £10.50 The Smoky £11.95 Severn and Wye Valley Smoked salmon, dill cream cheese. Some dishes may contain allergens – please speak to your server for further information before ordering Main Courses: Roast rump of Welsh Mountain Lamb £18.50 Slow cooked pulled lamb croquette, spring onion and rosemary mash, Fresh vegetables, red wine jus. -

Nothing Brings - PEOPLE TOGETHER - Like Good Food

NADOLIG LLAWEN GYDA CASTELL HOWELL 2020 HOWELL CASTELL GYDA NADOLIG LLAWEN CHRISTMAS HOME DELIVERY BROCHURE 2020 Nothing brings - PEOPLE TOGETHER - like good food... www.chfoods.co.uk | Order: 01269 846 080 Nadolig Llawen May your Christmas sparkle Dear Customer, Introducing our new and exclusive 2020 Christmas Retail Catalogue – our first ever brochure created for the public. 2020 has been a year of unprecedented challenges and we’re hugely thankful for the support we’ve received via our Click & Collect service and Cash & Carry. As a result, we’ve produced a dazzling festive offering of traditional favourites and inspirational modern alternatives. Our passion for diverse regional produce features throughout this collection and champions cultural tastes for a contemporary Christmas. With thousands of products to choose from, may your starters be sumptuous, mains be mouth-watering and desserts be delectable – this truly is your definitive guide to everything you’ll need for the most wonderful time of the year! Merry Christmas, Nadolig Llawen Brian Jones MBE, Managing Director CHRISTMAS HOME DELIVERY BROCHURE - 2020 Merry ChristmasStarters Castell Howell Foods Christmas 2020 | 1 Contents Lets get the party going... 3 Main Course 9 Starters CONTENTS 3. STARTERS & BUFFET Start as you mean to go on with this irresistible selection of entrees, selected to suit traditional tastes as well the more extravagant palate. 9. MAIN COURSES May your main courses dazzle with our mouth-watering array of products, chosen to suit all tastes and dietary requirements. 15. DESSERTS 15 This decadent and indulgent selection of Desserts desserts are like nothing you’ll have tasted before. -

A Cheesemonger's History of the British Isles

A Cheesemonger’s History of the British Isles First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Profile Books 3 Holford Yard, Bevin Way London WC1X 9HD www.profilebooks.com 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Typeset in Sina to a design by Henry Iles. Copyright © Ned Palmer 2019 The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-1788161183 e-ISBN 978-1782834755 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A. on Forest Stewardship Council (mixed sources) certified paper. A Cheesemonger’s History of the British Isles Ned Palmer For Imo, my constant solace and in memory of Mary Holbrook 1938–2019 Contents Introduction Fresh out of Red Leicester . 7 Chapter One . 11 Neolithic feasting 4000 bce–43 ce Sleightlett Chapter Two ............................................... 39 What the Romans did for our cheese 43 ce–1066 Spenwood and Wigmore Chapter Three ............................................ 73 The benefit of monks 1066–1348 Milleens Chapter Four ............................................ 115 Market forces 1348–1547 Gorwydd Caerphilly Chapter Five ............................................. 153 Big cheese 1547–1688 Appleby’s Cheshire Chapter Six ............................................... 189 The birth of a brand 1688–1837 Stichelton Chapter Seven . 217 Ploughman’s lunch 1837–1901 Westcombe Cheddar Chapter Eight .......................................... -

REVIEW of CONTROLS for PATHOGEN RISKS in SCOTTISH ARTISAN CHEESES MADE from UNPASTEURISED MILK Catherine Donnelly, Microbiological Consultant

REVIEW OF CONTROLS FOR PATHOGEN RISKS IN SCOTTISH ARTISAN CHEESES MADE FROM UNPASTEURISED MILK Catherine Donnelly, Microbiological Consultant DECEMBER 2018 Acknowledgements Food Standards Scotland and Catherine Donnelly would like to thank the Specialist Cheesemakers Association (SCA) for permitting the use of their microbiological data for this report. 1 Table of contents Glossary of Terms 4 Lay Summary and Key Recommendations 7 1. Introduction 9 1.1 Background 9 1.2 Overall Project Aims 12 1.3 Methodology 13 2. CHAPTER 1: Categorisation of cheese types commonly used in the UK 15 and critical control points for each stage of the cheesemaking process 2.1 Cheese types produced in the UK (with focus on Scotland): 15 Categorisation using Codex criteria 2.2 Control of Pathogens of Concern and Controlling Parameters during 21 Cheesemaking 2.2.1 Raw Drinking Milk vs. Raw Milk for cheesemaking 21 2.2.2 Microbial safety of cheeses made from raw milk 22 2.2.3 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) 27 2.2.3.1 General Characteristics 27 2.2.3.2 STEC Reservoirs 28 2.2.3.3 UK Policy Position on STEC and legal requirements 31 2.2.3.4 STEC outbreaks from milk sources 32 2.2.3.5 STEC in Cheese 33 2.2.3.6 STEC outbreaks associated with raw milk cheese 36 2.2.4 Salmonella 39 2.2.4.1 General Characteristics 39 2.2.4.2 Fate of Salmonella in Cheesemaking 40 2.2.4.3 Salmonella outbreaks associated with raw milk cheese 41 2.2.5 Listeria monocytogenes 42 2.2.5.1 General Characteristics 42 2.2.5.2 Listeria spp. -

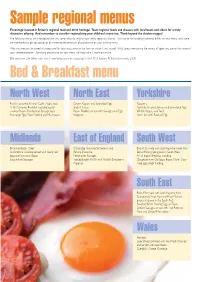

Sample Regional Menus

6476_BFF BuyGuide'05 ƒ WEBv 30/6/05 3:28 pm Page 12 Sample regional menus Encourage interest in Britain’s regional food and drink heritage! Team regional foods and cheeses with local beers and ciders for a truly distinctive offering. And remember to consider regionalising your children’s menu too. Think beyond the chicken nugget! The following menus are intended to give you some ideas for making your menu regionally distinct. This may be by including traditional dishes on your menu (and some are mentioned to get you going) or by increasing the emphasis of provenance on your existing menu. Why not mention the breed of sheep used for your roast lamb or the farm on which it was raised? What about mentioning the variety of apple you use or the name of your cheese producer? Specifying provenance on your menu will help make it more distinctive. Did you know £34 billion each year is now being spent on eating out in the UK? (Horizons FS Limited research, 2005) Bed & Breakfast menu North West North East Yorkshire Freshly squeezed Keswick Codlin Apple Juice. Craster Kippers and Scrambled Eggs. Popovers. A full Cumbrian Breakfast including locally- Singin’ Hinnies. Yo r kshire Smoked Salmon and Scrambled Eggs. smoked Bacon, Cumberland Sausage, local Bacon Floddies served with Sausages and Eggs. Whitby Kippers and Toast. free-range Eggs, Black Pudding and Mushrooms. Kedgeree. Yo rk Ham with Poached Egg. Midlands East of England South West Brummie Bacon Cakes. Cambridge Favourite Strawberry and Bucks Fizz made with sparkling wine made from Staffordshire Oatcake served with locally-laid Banana Smoothie. -

Retail Medal Winners by Class

British Cheese Awards 2019 Retail Medal Winners by Class RETAILER CLASSES 098 Fresh / Soft White / Semi-soft 1001 Aldi Stores Ltd The Abergavenny Fine Food Welsh Honey & Ginger Soft Goats Cheese Bronze Co. 1002 Co-operative Group Lactalis Co-op Somerset Brie Silver 1004 Marks and Spencer PLC Grahams Natural Cottage Cheese Silver 1005 Marks and Spencer PLC Abergavenny Fine Foods Goats Cheese Log (0086490) Silver 1006 Marks and Spencer PLC Butlers Kidderton Ash (0011990) Gold 1007 Marks and Spencer PLC Caws Cenarth Golden Cenarth (00489904) Silver 1008 Marks and Spencer PLC Butlers Ravensoak Goats Cheese (00451697) Gold 1011 Tesco Plc Camembert Silver 1012 Tesco Plc Finest Kidderton Ash Goats Cheese Gold 099 Cheddar [up to 12 months] 1017 Marks and Spencer PLC Ashley Chase Wookey Hole Cheddar (00373784) Gold 1019 Marks and Spencer PLC Lye Cross Farm Organic Mature Cheddar Silver 1020 Marks and Spencer PLC Dairy Crest Davidstow Cornish Cove Medium Cheddar Bronze 1021 Tesco Plc Mature White Cheddar Silver 0100 Cheddar [over 12 months] 1027 Marks and Spencer PLC Dairy Crest 3 Year Old Cruncher Silver 1028 Marks and Spencer PLC Dairy Crest Cornish Cove Extra Mature Bronze 1030 Tesco Plc Finest Vintage English Cheddar Gold 0101 Red Leicester 1033 Aldi Stores Ltd Joseph Heler Emporium Red Leicester Bronze 1039 Marks and Spencer PLC Arla Red Leicester (00199841) Silver 1040 Marks and Spencer PLC Arla Red Leicester (00199841) Bronze 1041 Tesco Plc Red Leicester Gold 0102 Other Territorials 1044 Lidl UK GmbH Lidl - Valley Spire Cheshire Cheese (only -

Product List March 2017

Over 50 Year’s The Experience in the Fine Food industry Cheese Man Friendly Van sales Wholesalers of fine Cheeses, Charcuterie service and Gourmet products Local Cheese Product Specialist Quality Products @ Competitive List Prices January 2017 Family Run Sussex Based Business && Call us Now on THE CHEESE MAN Unit 20/21 Hove Enterprise Centre 01273 412444 Basin Road North Portslade East Sussex BN41 1UY Tel: 01273 412444 www.thecheeseman.co.uk [email protected] @CheeseManSussex The Cheese Man The Cheese Man We at The Cheese Man are passionate about cheese and fine foods, we have over 50 years experience in the fine food industry, with a wealth of knowledge to share with our customers. We carry an extensive range of cheeses and gourmet products from around the world and as a local family run company are proud to promote Sussex cheeses and local gourmet products. We are ever mindful of how important food miles and environmental issues are to our customers, and working closely with local cheese makers we hope to develop local awareness of quality cheeses from the surrounding areas. In sharing our knowledge and expertise we hope this list will highlight what we already know here at The Cheese Man, that some of the finest ranges of cheeses are on our very doorstep ready to be delivered by the only Cheese Specialist Van Sales Company in Sussex…. In our fleet of temperature controlled vehicles. Contents : Page 1. Local Cheeses 5. English Cheeses 12. English Goats 13. Scottish Cheeses 14. Irish Cheeses 15. Welsh Cheeses 16. French Cheeses 20. -

Wholesalers of Fine Cheeses, Charcuterie and Gourmet Products

Over 50 Year’s Experience in the The Fine Food industry Cheese Man Friendly Van sales Wholesalers of fine Cheeses, Charcuterie service and Gourmet products Local Cheese Product Specialist Quality Products @ Competitive List Prices August 2020 Family Run Sussex Based Business && Call us Now on THE CHEESE MAN 1 Basin Road South 01273 412444 Portslade East Sussex BN41 1WF Tel: 01273 412444 www.thecheeseman.co.uk [email protected] @CheeseManSussex The Cheese Man The Cheese Man We at The Cheese Man are passionate about cheese and fine foods, we have over 50 years experience in the fine food industry, with a wealth of knowledge to share with our customers. We carry an extensive range of cheeses and gourmet products from around the world and as a local family run company are proud to promote Sussex cheeses and local gourmet products. We are ever mindful of how important food miles and environmental issues are to our customers, and working closely with local cheese makers we hope to develop local awareness of quality cheeses from the surrounding areas. In sharing our knowledge and expertise we hope this list will highlight what we already know here at The Cheese Man, that some of the finest ranges of cheeses are on our very doorstep ready to be delivered by the only Cheese Specialist Van Sales Company in Sussex…. In our fleet of temperature controlled vehicles . Contents : Page 3-7. Local Cheeses 7-15. English Cheeses 15-16 English Goats 17. Scottish Cheeses 17-18 Irish Cheeses 18-19. Welsh Cheeses 19-23. French Cheeses 24. -

Waterloo 2019 MENU

Small Plates for grazing and sharing: £4.95 each or 3 for £14 Cold: Hot: (v) Hummus with Feta & Piri Piri Chargrilled Chicken Wings Charred flatbread soldiers Spicy BBQ glaze The Bridge ‘Hip Crisp’ and veggie platter Black pudding Bon bons Aioli, salsa and Chilli and BBQ dipping sauces Sautéed Chorizo, Grain mustard and apple mayonnaise (v) Marinated mixed olives Lamb Kofte Mint and lemon dressing Locally made Bread platter Oil and aged Balsamic vinegar (v) Chargrilled Halloumi Honey, chilli and lime dressing Starters Traditional ‘Cawl Cennin’ £6.50 Leek and potato soup with melted Caerphilly cheese topping (v) Pantysgawn Goat’s cheese £6.25 Savoury Panna Cotta of Pantysgawn Goats cheese with beetroot. Taco Ty £7.50 Soft corn House taco of King prawns, chilli, ginger and spring onion, with salad, salsa & aioli. Chicken Liver and Welsh Penderyn Whisky pate £6.25 Crostini and apple chutney (vegan) Sweet potato and red lentil Dahl Croquettes £6.25 Chilli spiced mango sauce Pizzas The Welsh £12.50 Pulled slow cooked Lamb with leek and laverbread The Bridge Special £12.50 Rump steak, red onion and goat’s cheese (v) The Forager £10.95 Mixed mushrooms, spinach, red onion and balsamic glaze The Snowdon Dragon £11.50 Spicy Chorizo, Pepperoni, Pardon peppers, red onion and chilli (v) Classic Margherita £10.50 The Smoky £11.95 Severn and Wye Valley Smoked salmon, dill cream cheese. Main Courses: Roast rump of Welsh Mountain Lamb £18.50 Slow cooked pulled lamb croquette, spring onion and rosemary mash, Fresh vegetables, red wine jus. Roast Supreme of Chicken £13.95 Smoked bacon and leek stuffing, bubble and squeak, sautéed vegetables, white wine sauce. -

International Cheese & Dairy Awards Nantwich 2019 Est.1897

INTERNATIONAL CHEESE & DAIRY AWARDS NANTWICH 2019 EST.1897 DAIRY PRODUCE CATALOGUE Tuesday 30th and Wednesday 31st July 2019 The Showground, Nantwich CW5 8LD VISIT INTERNATIONALCHEESEAWARDS.CO.UK 8+89"& +2"6#96+# .(" 9: #9 GGPRPB`FE`U`IFYYUDPB`PUTUG6IUcBTEHXPDaR`aXBR3XHBTPYB`PUTY '27#527'320!&##6#&"'5A@5"6 227@'!& ! " #$ % & ' ! ()) 1BXWaFF!U UXEPTB`UXY1PQF2PFRERPY`BPX5BPYCFDQBTE4F`FX5eBT !IFFYF!USVF`P`PbF6FDXF`BXeEXPBT0BcXFTDF !IFFYF!USVF`P`PUT!U UXEPTB`UX"BbPE@FRRY !IFFYF7XBEF6FDXF`BXeEXPBT0BcXFTDF&6aYBT%UUEcPT (aEHFY6FDXF`BXe"BP@PRRPBSY !IPFG6`FcBXE!IXPY#EcBXEY3 #7"1'$6795 YYPY`BT`!IPFG6`FcBXEY(PRR&UEHYUT%3!UTcBe6BRRe6SP`I234UURFe 4XFYY&1FEPB"FCCPF6`FcBX`(35FESBTSe7aXQ 7XUVIPFYf6FDXF`BXe0PTEB(UTFY 5FYaR`Y(BYUT!UUQF '!!USVF`P`PUT5FGFXFF537IUXVF (** 5a`I&aRSFRPYUT7BeRUX0PTEB0FcPY @PRRPBSY436VFTDFX 3%XFY`e(aRPF FT` 1BDEUTBRE)30UbF43!RBXQF6BXBIEF@P` " % +, + - . / 0 /1 / 2 - / .1* " % +, # $ 1 " 3 + 4 # 5 6.+ " 7 , 227@'!&&6387&!&'5#6&3@ ()) !IBPXSBT1PDIBFR (UIT4BXQPT13533!3 "FVa`e!IBPXSBT323 aXXUcY#YW3 9PDF!IBPXSFT%3!BRRcUUE#YW&53(UITYUT#YW &UT37XFBYaXFX53@UUEY#YW3 #dFDa`PbF"PXFD`UX(UIT63 XUUSIBRR1 #&5UCFX`#BXERFe#YW ., 53"BXRPTH`UT435UCPTYUT23 UTFRR43@PTcBXE#39BaHIBT3@PRRPBSY ., 3 BXXPF(30USBY23"BXRPTH`UT35BPYCFDQ & #) ' "3(UITYUT1XY130B`IBS53 BQFX(3%34BXQPT 36PSDUF&3 3 XUcT1XY53&aRSF(363 XUUSIBRR13 3#31XY(3 PXDIBRR 1XY&31BX`eT#323@PRRPBSY536SP`I1XY436SP`I(3#30FB8!BT`BC9$!1XY(3#30FB435UCPTYUT23 UTFRR53"BXRPTH`UT 73234BRSFX#39BaHIBT1XY!34FXDPbBR1XY13&BSSFXYRFe1XY13(UITY`UT1XY&3@UUEcBXE1XY73