A Cheesemonger's History of the British Isles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Price List - Cook School

PRICE LIST - COOK SCHOOL TO PLACE AN ORDER: CALL US ON 01563 55008 OPTION 1 BETWEEN 8AM AND 12PM DAILY, COLLECT FROM 1PM TO 8PM THE SAME DAY. COLLECT FROM BRAEHEAD FOODS WAREHOUSE, TO THE REAR OF BRAEHEAD FOODS/COOK SCHOOL. MINIMUM ORDER VALUE £35, MAXIMUM 1 BOX OF CHICKEN PP. Production Kitchen - Buffet Canape & Starters Product No Product Description UOM Sub Category Column1 Price SHOP041 CS SHOP STEAK & SAUSAGE PIE 1.2 KG EACH £11.00 SHOP048 CCS READY MEAL MINCE POTATOES PEAS AND CARROTS 345 G EACH £3.00 SHOP052 CSS READY MEAL LASAGNE 500G EACH £5.00 SHOP054 CSS READY MEALS CHICKEN BROCCOLI & PASTA BAKE 450 G EACH £4.00 SHOP058 CSS READY MEALS MACARONI CHEESE 400G EACH £3.00 Production Kitchen - Burgers Product No Product Description UOM Sub Category Column1 Price PRO01895 BHF VENISON BURGER 5 x 170g (Frozen) EACH PK Burgers £13.20 Production Kitchen - Hot Wets Product No Product Description UOM Sub Category Column1 Price PRO02003 BHF WHL BEEF & SMOKED PAPRIKA MEATBALLS IN TOMATO SAUCE 2.5Kg (Frozen)EACH Pre 10 PK Hot Wets £28.01 PRO02042 BHF BEEF LASAGNE 2.5Kg (FROZEN) EACH PK Hot Wets £27.64 PRO02015 BHF CAULIFLOWER MAC & CHEESE CRUMBLE 2.5Kg (Frozen) (Vegetarian) Pre 10EACH PK Hot Wets £24.07 PRO02019 BHF CHICK PEA, SQUASH & VEGETABLE CURRY 2.5Kg (Frozen) (Vegetarian) PreEACH 10 PK Hot Wets £21.69 PRO02004 BHF CHICKEN CASSEROLE WITH HERB DUMPLINGS 2.5Kg (Frozen) Pre 10 EACH PK Hot Wets £29.44 PRO02005 BHF CHICKEN TIKKA MASALA CURRY 2.5Kg (Frozen) Pre 10 EACH PK Hot Wets £25.36 PRO02006 BHF CHICKEN, CHICK PEA & CORIANDER TAGINE 2.5Kg -

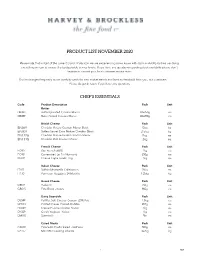

Copy of Product List November 2020

PRODUCT LIST NOVEMBER 2020 Please note that in light of the current Covid-19 situation we are experiencing some issues with stock availability but we are doing everything we can to ensure the best possible service levels. If you have any questions regarding stock availability please don't hesitate to contact your local customer service team. Our list changes frequently as we carefully watch for new market trends and listen to feedback from you, our customers. Please do get in touch if you have any questions. CHEF'S ESSENTIALS Code Product Description Pack Unit Butter DB083 Butter Unsalted Croxton Manor 40x250g ea DB089 Butter Salted Croxton Manor 40x250g ea British Cheese Pack Unit EN069 Cheddar Mature Croxton Manor Block 5kg kg EN003 Butlers Secret Extra Mature Cheddar Block 2.5kg kg EN127G Cheddar Mature Grated Croxton Manor 2kg ea EN131G Cheddar Mild Croxton Manor 2kg ea French Cheese Pack Unit FC417 Brie French (60%) 1kg ea FC431 Camembert Le Fin Normand 250g ea FG021 Chevre Capra Goats' Log 1kg ea Italian Cheese Pack Unit IT042 Buffalo Mozzarella Collebianco 200g ea IT130 Parmesan Reggiano 24 Months 1.25kg kg Greek Cheese Pack Unit GR021 Halloumi 250g ea GR015 Feta Block - Kolios 900g ea Dairy Essentials Pack Unit DS049 Full Fat Soft Cheese Croxton (25% Fat) 1.5kg ea DC033 Clotted Cream Cornish Roddas 907g ea DC049 Crème Fraîche Croxton Manor 2kg ea DY009 Greek Yoghurt - Kolios 1kg ea DM013 Buttermilk 5ltr ea Cured Meats Pack Unit CA049 Prosciutto Crudo Sliced - Dell'ami 500g ea CA177 Mini BBQ Cooking Chorizo 3x2kg kg 1 HBX Chocolate -

2022/23 Complete Wedding Service

2022/23 COMPLETE WEDDING SERVICE 01443 665803 | www.valeresort.com YOUR WEDDING ONE PRICE. EVERYTHING INCLUDED Congratulations, you are about to embark on one of the most memorable events in your life - your wedding. Naturally, nothing less than perfection will do and a whole host of exciting decisions lie before you; the dress, the flowers, the honeymoon and of course, the venue. We’ll help you celebrate the most memorable day of your life in one of the most beautiful wedding venues in Wales. The idyllic setting, exquisite landscaped gardens, sweeping staircases and classic terraces inspire beautiful photography and a day that you’ll cherish and remember for years to come. We cater for your reception with versatile rooms that create the right atmosphere - from intimate, romantic gatherings to show-stopping, lavish celebrations. The stunning Morgannwg Suite opens onto a balcony with sweeping staircases to the terrace below, and beautiful landscaped gardens that provide the ideal backdrop for your photographs. By contrast, the impressive Castle Suite offers a lavish celebration in a dramatic setting with high ceilings, wall to floor windows plus an exclusive bar and balcony terrace for you and your guests. For smaller wedding parties, the Pendoylan Suite, Cowbridge Lounge and Hensol Suite offer the right ambience for intimate gatherings while still guaranteeing a day to remember! 01443 665803 | www.valeresort.com WEDDING CEREMONY Exchanging your vows in a beautiful setting makes those precious words even more special. Our superb choice of function suites enables you to select the perfect setting to say “I do”. Whether your ceremony is an intimate gathering or a celebration for 400 guests, our civil ceremony license allows you to enjoy every aspect of your special day here at the Vale Resort. -

“Quality Produce with a Scottish Flavour- Simply Cooked.”

“Quality produce with a Scottish flavour- simply cooked.” STARTERS Cock a leekie soup, prune savarin £6.00 Smoked salmon blinis, horseradish crème friache £9.00 Cod flakes, smoked egg yolk, pink firs, clam juices £9.00 Shrimp and crayfish cocktail £9.00 Pan seared scallops, marrowfat pea puree, pancetta, curry oil £10.00 Pressed foie gras parfait, toasted brioche, Scottish chantrelles £10.00 Roast pigeon breasts ,beansprout salad, sherry dressing £9.00 Butternut squash and ameretti ravioli, sage butter £7.00 Goats cheese, puff pastry, pear and walnut salad £6.00 GRILLS All our beef comes from quality-assured, grass-fed cattle from Scottish Farms. We use prime Scottish beef and are proud to be a member of The Scotch Beef Club. 8oz “Black Gold” fillet steak (Premium quality beef from Mathers of Inverurie, Aged 28 days) £30.00 10 oz “Caledonian Crown” ribeye steak (World renowned for its flavour and succulence, grass fed in Scotlands Highlands) £26.00 8 oz “Scotch Premier” sirloin steak (The royal warranted selected beef from Aberdeenshire) £28.00 Surf and Turf (Your choice of steak with seared Hebridean king Prawns in garlic and herb butter) £6.00 supplement Butterflied double breast sesame marinated chicken £16.00 10 oz Double loin lamb chop £20.00 SAUCES Peppercorn and Brandy, Bernaise, Arran Mustard, Creamy Lanark Blue £3.00 MAINS Confit pork belly and fillet, Stornoway black pudding, fermented apple foam £18.00 Smoked duck breast, confit leg croquette, creamed sprouts and cranberries £18.00 Basil roasted lamb rump, boulangere potato, sundried tomato jus £17.00 Beef featherblade and medallion, parsnip puree, lardons and baby onions and red wine £21.00 Venison loin and confit shin, sweet red cabbage, valrhona chocolate scented sauce £22.00 Chanterelle risotto, poached egg, truffle foam £13.00 Spinach and parmesan flan, aubergine caviar, olive salsa £13.00 FISH We are totally committed to using locally caught fish from responsible suppliers and sustainable fisheries. -

Saint Andrew's Society of San Francisco

Incoming 2nd VP Welcome Message By Alex Sinclair ince being welcomed to the St. Andrew’s community almost Stwo years ago, I have been filled with the warmth and joy that this society and its members bring to the San Francisco Bay Area. From dance, music, poetry, history, charity, and edu- cation the charity’s past 155 years has celebrated Scottish cul- ture in its contributions to the people of California. I have been grateful to the many friendly faces and experiences I have had since rediscovering the Scottish identity while at the society. I appreciate everyone who has supported my nomination as an officer within the organisation, and I will try my best no matter Francesca McCrossan, President your vote to support your needs as members and of the success November 2020 of the charity at large. President’s Message Being an officer at the society tends to need a wide range of skills and challenges to meet the needs of the membership and Dear St. Andrew’s Society, the various programs and events we run through the year, in the Looking towards the New Year time of Covid even more so. In my past, I have been a chef, a musician, a filmmaker, a tour manager, a marketeer, an entre- t the last November Members meeting, I was reelected as preneur, an archivist and a specialist in media licencing and Ayour President, and I thank the Members for the honor to digital asset management. I hold an NVQ in Hospitality and Ca- be able to serve the Society for another year. -

F I N E C H E E S E & C O U N T

F I N E C H E E S E & C O U N T E R 2 0 1 9 F I N E C H E E S E & C O U N T E R 2 0 1 9 F I N E C H E E S E & C O U N T E R 2 0 1 9 U S E F U L I N F O R M A T I O N C O N T E N T S Your area manager : S = Stock Items RECOMMENDATIONS 4 Mobile Telephone : Any item that is held in stock can be ordered up until 12 noon and will arrive on your usual delivery day. CELEBRATION CHEESE 6 Your office contact: Office Telephone: 0345 307 3454 PO = Pre-order Items SCOTTISH CHEESE 8 Cheese & Deli Team : 01383 668375 Pre-order items need to be ordered by 12 noon on a Monday and will be ready from Thursday and delivered to ENGLISH CHEESE 12 Office email: [email protected] you on your next scheduled delivery day. Office fax number : 08706 221 636 WELSH & IRISH CHEESE 18 PO **= Pre-order Items Your order to be in by: Pre-order items recommended for deliveries arriving CONTINENTAL CHEESE 20 Pre-orders to be in by: Monday 12 noon Thursday and Friday only CATERING CHEESE, 24 Minimum order : ** = Special Order Items DAIRY & BUTTER (minimum orders can be made up of a combination of Special order items (such as whole cheeses for celebration product from chilled retail and ambient) cakes) need to be ordered on Monday by 12 noon week 1 CHARCUTERIE, MEATS & DELI 26 for delivery week 2. -

Party Catering to Collect Autumn/Winter 2015/2016

PARTYPARTY CATERING CATERING TO COLLECTTO COLLECT AUTUMN/WINTERSPRING/SUMMER 2015/2016 2013 wwwww.athomecatering.co.ukw.athomecatering.co.uk CONTENTS BREAKFAST MENU (Minimum 10 covers) Contents Page PASTRY SELECTION £4.75 per person Miniature Croissant Miniature Pain au Raisin Breakfast menu 1 Miniature Pain au Chocolat Overstuffed sandwiches & sweet treats 2 - 3 CONTINENTAL £7.50 per person Freshly made salads 4 - 7 Miniature Croissant Miniature Pain au Raisin Fresh home made soups 8 Miniature Pain au Chocolat Baguette with Butter & Preserves Luxury soups, stocks & pasta sauces 9 Seasonal Fruits Cocktail/finger food 10 - 11 Freshly squeezed Orange Juice Starters & buffet dishes 12 - 13 EUROPEAN £9.50 per person Miniature Croissant Quiches & savoury tarts 14 Miniature Pain au Raisin Frittatas & savoury items 15 Miniature Pain au Chocolat Baguette & Focaccia with Butter & Preserves Chicken dishes 16 - 17 Serrano Ham with Caperberries & Olives Manchego cheese with Cherry Tomatoes & Cornichons Beef dishes 18 - 19 Muesli with Greek yogurt, Honey & Almonds Freshly squeezed Orange Juice Lamb dishes 20 - 21 Pork 22 AMERICAN £11.50 per person Miniature Croissant Duck & game 23 Miniature Pain au Raisin Miniature Pain au Chocolat Fish & seafood dishes 24 - 25 Lemon, Honey & Poppy seed Muffins Vegetarian dishes 26 Blueberry Muffins Poppy seed Bagels with Smoked Salmon, Cream cheese, Lemon & Chives Vegetable side dishes 27 Maple Cured bacon & Tomato rolls Fruit salad with Fromage Frais Whole puddings 28 - 29 Freshly squeezed Orange Juice Individual -

Port, Sherry, Sp~R~T5, Vermouth Ete Wines and Coolers Cakes, Buns and Pastr~Es Miscellaneous Pasta, Rice and Gra~Ns Preserves An

51241 ADULT DIETARY SURVEY BRAND CODE LIST Round 4: July 1987 Page Brands for Food Group Alcohol~c dr~nks Bl07 Beer. lager and c~der B 116 Port, sherry, sp~r~t5, vermouth ete B 113 Wines and coolers B94 Beverages B15 B~Bcuits B8 Bread and rolls B12 Breakfast cereals B29 cakes, buns and pastr~es B39 Cheese B46 Cheese d~shes B86 Confect~onery B46 Egg d~shes B47 Fat.s B61 F~sh and f~sh products B76 Fru~t B32 Meat and neat products B34 Milk and cream B126 Miscellaneous B79 Nuts Bl o.m brands B4 Pasta, rice and gra~ns B83 Preserves and sweet sauces B31 Pudd,ngs and fru~t p~es B120 Sauces. p~ckles and savoury spreads B98 Soft dr~nks. fru~t and vegetable Ju~ces B125 Soups B81 Sugars and artif~c~al sweeteners B65 vegetables B 106 Water B42 Yoghurt and ~ce cream 1 The follow~ng ~tems do not have brand names and should be coded 9999 ~n the 'brand cod~ng column' ~. Items wh~ch are sold loose, not pre-packed. Fresh pasta, sold loose unwrapped bread and rolls; unbranded bread and rolls Fresh cakes, buns and pastr~es, NOT pre-packed Fresh fru~t p1es and pudd1ngs, NOT pre-packed Cheese, NOT pre-packed Fresh egg dishes, and fresh cheese d1shes (ie not frozen), NOT pre-packed; includes fresh ~tems purchased from del~catessen counter Fresh meat and meat products, NOT pre-packed; ~ncludes fresh items purchased from del~catessen counter Fresh f1sh and f~sh products, NOT pre-packed Fish cakes, f1sh fingers and frozen fish SOLD LOOSE Nuts, sold loose, NOT pre-packed 1~. -

CANAPE SELECTOR Vegetarian Fish Meat & Poultry

Standard version CANAPE SELECTOR Vegetarian Roasted cherry tomato on a parmesan shortbread with whipped cream cheese & chives on white versionButternut squash arancini with red pepper ketchup A selection of vegetable or smoked salmon sushi with wasabi mayo Black truffle, potato & gruyere tart Whipped goats cheese on oat biscuit with baked fig and heather honey Baby baked potatoes served warm with sour cream chive Lanark blue cheese on a pecan tuille with juniper jelly Selection of flat breads & bread sticks with bahbah ganoush & humous mono version Crisp little gem lettuce hearts filled with waldorf fruit & nuts All of the above can be done in a vegan format) Fish Isle of Mull cheddar & smoked haddock fritter with cullen skink shot Crispy langoustine croquette with shellfish essence Smoked salmon & dill mousse with creamed horseradish mono on white Tartlet of west coast crab with spiced mango version Baby baked potatoes served warm with chive crème fraiche & avruga caviar Meat & Poultry Crispy haggis balls with Arran mustard mayo Lady bite sized Yorkshire puddings filled with roast beef & creamed horseradish Carpaccio of Scottish beef on crisp parmesan shortbread Chicken liver parfait on a ginger bread wafer with Cumberland dressing Lemon chicken sticks with coriander & lime mayo Slow cooked belly of pork spoons with Asian slaw Prosecco Calogera – Italy Calogera Rose Spumante - Italy BIG BITE CATERING LIMITED, 67 GOWAN BRAE, CALDERCRUIX, AIRDRIE, ML6 7RB Website: www.bigbitecatering.co.uk Email: [email protected] Tel: 01236 842972 -

a - TASTE - of - SCOTLAND’S Foodie Trails

- a - TASTE - of - SCOTLAND’S Foodie Trails Your official guide to Scottish Food & Drink Trails and their surrounding areas Why not make a picnic of your favourite Scottish produce to enjoy? Looking out over East Lothian from the North Berwick Law. hat better way to get treat yourself to the decadent creations to know a country and of talented chocolatiers along Scotland’s its people and culture Chocolate Trail? Trust us when we say Wthan through its food? that their handmade delights are simply Eat and drink your way around Scotland’s a heaven on your palate – luscious and cities and countryside on a food and drink meltingly moreish! On both the Malt trail and experience many unexpected Whisky Trail and Scotland’s Whisky culinary treasures that will tantalise your Coast Trail you can peel back the taste buds and leave you craving more. curtain on the centuries-old art of whisky production on a visit to a distillery, while a Scotland’s abundant natural larder is pint or two of Scottish zesty and refreshing truly second to none and is renowned for ales from one of the breweries on the Real its unrivalled produce. From Aberdeen Ales Trail will quench your thirst after a Angus beef, Stornoway Black Pudding, day of exploring. And these are just some Arbroath Smokies and Shetland salmon of the ways you can satisfy your craving for and shellfish to Scottish whisky, ales, delicious local produce… scones, shortbread, and not to forget haggis, the range is as wide and diverse as Peppered with fascinating snippets of you can possibly imagine. -

Wedding Packages

2022/23 COMPLETE WEDDING SERVICE 01443 665803 | www.hensolcastle.com YOUR CASTLE AWAITS A 17th Century Grade 1 listed castle, exclusively yours‡ for your special day. Situated in a breathtaking estate that contains a stunning 15 acre Serpentine Lake and soaring trees. Hensol Castle is the perfect setting for any bride wanting a fairytale wedding. The lake and gardens, turreted castle, sweeping staircases and castle reception rooms provide the most memorable photogenic opportunities imaginable and that’s not all... WITH OUR COMPLIMENTS ♥ Exclusively yours for the day‡ ♥ Red carpet on arrival ♥ Silver cake stand and knife ♥ Complimentary table menus ♥ Complimentary bedroom at the Vale Resort for the happy couple ♥ One months complimentary use of our Health and Racquets Club ♥ Round of golf for the groom and three friends† ♥ 20% spa discount for the bride, one month prior to your wedding ♥ Complimentary parking ♥ Complimentary dinner on your first anniversary †Handicap certificates required. ‡Only one wedding per day at the venue. 01443 665803 | www.hensolcastle.com WEDDING BREAKFAST SANDRINGHAM £48.95 per person STARTERS Roasted Plum Tomato and Pimento Bisque VG Grilled foccacia, crisp basil Pork Belly and Confit Duck Rillettes Spiced apple chutney, grilled sourdough toast Hot Smoked Salmon Tian Dill crème fraiche and fresh horseradish Feta, Olive and Mediterranean Vegetable Tart V Pickled red onion, tzatziki, shaved cucumber ribbons MAIN COURSE Pan Roasted Chicken Breast G Olive and chorizo sauce, whipped potatoes, braised kale Pave of -

View Our Brochure

www.braeheadfoods.co.uk "Braehead Foods have been huge supporters of the industry for many years; their contribution to many of our events has enabled us to provide multiple scholars for the emerging talent for our Industry. How to The opportunities that Braehead Foods have provided for the industry have allowed great learning experience for place an order individuals to take both locally, nationally & internationally. We are very grateful for their support." Contact us on - David Cochrane t: +44 (0)1563 550 008 HIT Scotland e: [email protected] www.braeheadfoods.co.uk 7 Moorfield Park, Kilmarnock, Ayrshire KA2 OFE @Braehead_Foods @BraeheadFoods BraeheadFoodsLimited BraeheadFoods Our delivery frequency varies between 4 to 6 days a week across the UK. Please speak to our Customer Service Team to check out your own specific distribution service. Why choose Braehead Foods? Quality About us... Braehead Foods is one of Scotland’s largest Service independent food wholesalers who have been Traceability supplying Chefs across the UK and Europe with the finest quality ingredients for over 30 years. Innovation Supplying everything from the finest Scottish game to quality Reliability chilled, ambient and frozen foods, we deliver across the UK daily. Processing game birds in our AA Grade BRC Accredited Site, we can accommodate various finishing styles whether its oven ready, long legged or breast meat. As members of the British Game Alliance, Braehead Foods not only support the wild game industry, but are part of a quality assured programme where all steps from field to plate are being carried out in a safe and legal manner, ensuring compliance throughout.