Scripture and Spirituality in Early-Modern Biblical Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Puritan Use of Imagination

A Quarterly Journal for Church Leadership Volume 10 • Number 1 • Winter 2001 THE PURITAN USE OF IMAGINATION 7Piety is the root of charity. JOHN CALVIN Wouldest thou see a Truth within a Fable? I I heir ministers, whom Wesley consulted about their con Then read my fancies, they will stick like Burs victions, were trained at Halle, which was the centre of the ... come hither, Lutheran movement that most affected Evangelical origins: And lay my Book thy head, and Heart together. Pietism. Philip Spener had written in 1675 the manifesto of the movement, Pia Desideria, urging the need for repen Co wrote John Bunyan in his "Apology" to The Pilgrim's tance, the new birth, putting faith into practice and close o Progress at its first appearance in 1678.1 Time has proven fellowship among true believers. His disciple August him right. Few books, even of the powerful Puritan era, Francke created at Halle a range of institutions for embody make as lasting an impression on head and heart as his. ing and propagating Spener's vision. Chief among them God's truth is conveyed effectively by Bunyan's fiction.2 was the orphan house, then the biggest building in Europe, with a medical dispensary attached. It was to inspire both TRUTH ALONGSIDE FICTION Wesley and Whitefield to erect their own orphan houses Bunyan was certainly aware of the seeming inconsisten and Howel Harris to establish a community as centre of cy between "truth" and "fable." He had even sought the Christian influence at Trevecca. advice of his contemporaries about such an enterprise: DAVID W. -

University of Birmingham Delight in Good Books

University of Birmingham Delight in good books Wright, Gillian DOI: 10.1353/bh.2015.0002 License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Wright, G 2015, 'Delight in good books: Family, Devotional Practice, and Textual Circulation in Sarah Savage’s Diaries ', Book History, vol. 18, pp. 45-74. https://doi.org/10.1353/bh.2015.0002 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Published as above. Publication available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/bh.2015.0002 Checked Feb 2016 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

The Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal

FALL 2019 volume 6 issue 1 3 FROM RUTHERFORD HALL Dr. Barry J. York 4 FOUR CENTURIES AGO: AN HISTORICAL SURVEY OF THE SYNOD OF DORT Dr. David G. Whitla 16 THE FIRST HEADING: DIVINE ELECTION AND REPROBATION Rev. Thomas G. Reid, Jr. 25 THE SECOND HEADING - CHRIST’S DEATH AND HUMAN REDEMPTION THROUGH IT: LIMITED ATONEMENT AT THE SYNOD OF DORDT AND SOME CONTEMPORARY THEOLOGICAL DEBATES Dr. Richard C. Gamble 33 THE THIRD HEADING: HUMAN CORRUPTION Rev. Keith A. Evans 39 THE FOURTH HEADING: “BOTH DELIGHTFUL AND POWERFUL” THE DOCTRINE OF IRRESISTIBLE GRACE IN THE CANONS OF DORT Dr. C. J. Williams 47 THE FIFTH HEADING: THE PERSEVERANCE OF THE SAINTS Dr. Barry J. York STUDY UNDER PASTORS The theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary Description Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is the online theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary. Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is provided freely by RPTS faculty and other scholars to encourage the theological growth of the church in the historic, creedal, Reformed faith. Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is published biannually online at the RPTS website in html and pdf. Readers are free to use the journal and circulate articles in written, visual, or digital form, but we respectfully request that the content be unaltered and the source be acknowledged by the following statement. “Used by permission. Article first appeared in Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal, the online theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary (rpts.edu).” e d i t o r s General Editor: Senior Editor: Assistant Editor: Contributing Editors: Barry York Richard Gamble Jay Dharan Tom Reid [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] C. -

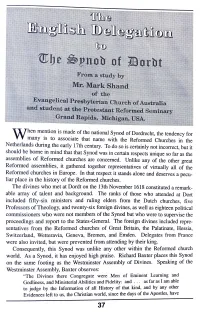

E of the National Synod of Dordrecht, the Tendency for W Many 1S to Associate That Name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands During the Early 17Th Century

hen m~ntion is ma?e of the national Synod of Dordrecht, the tendency for W many 1s to associate that name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands during the early 17th century. To do so is certainly not incorrect, but it should be borne in mind that that Synod was in certain respects unique so far as the assemblies of Reformed churches are concerned. Unlike any of the other great Reformed assemblies, it gathered together representatives of virtually all of the Reformed churches in Europe. In that respect it stands alone and deserves a pecu liar place in the history of the Reformed churches. The divines who met at Dordt on the 13th November 1618 constituted a remark able array of talent and background. The ranks of those who attended at Dort included fifty-six ministers and ruling elders from the Dutch churches, five Professors of Theology, and twenty-six foreign divines, as well as eighteen political commissioners who were not members of the Synod but who were to supervise the proceedings and report to the States-General. The foreign divines included repre sentatives from the Reformed churches of Great Britain, the Palatinate, Hessia, Switzerland, Wetteravia, Geneva, Bremen, and Emden. Delegates from France were also invited, but were prevented from. attending by their king. Consequently, this Synod was unlike any other within the Reformed church world. As a Synod, it has enjoyed high praise. Richard Baxter places this Synod on the same footing as the Westminster Assembly of Divines. Speaking of the Westminster Assembly, Baxter observes: "The Divines there Congregate were Men of Eminent Learning and Godliness, and Ministerial Abilities and Fidelity: and . -

THE SYNOD of DORT Many Reformed Churches Around the World Commemorate the Great Protestant Reformation Which Begun in Germany on October 31St 1517

THE SYNOD OF DORT Many Reformed Churches around the world commemorate the Great Protestant Reformation which begun in Germany on October 31st 1517. On that providential day, Martin Luther nailed his famed 95 Theses on the door of the castle church of Wittenberg. In no time, without Luther's knowledge, this paper was copied, and reproduced in great numbers with the recently invented printing machine. It was then distributed throughout Europe. This paper was to be used by our Sovereign Lord to ignite the Reformation which saw the release of the true Church of Christ from the yoke and bondage of Rome. Almost five hundred years have gone by since then. Today, there are countless technically Protestant churches (i.e. can trace back to the Reformation in terms of historical links) around the world. But there are few which still remember the rich heritage of the Reformers. In fact, a great number of churches which claim to be Protestant have, in fact, gone back to Rome by way of doctrine and practice, and some even make it their business to oppose the Reformers and their heirs. I am convinced that one of the chief reasons for this state of affair in the Protestant Church is a contemptuous attitude towards past creeds and confessions and the historical battles against heresies. When, for example, there are fundamentalistic defenders of the faith teaching in Bible Colleges, who have not so much as heard of the Canons of Dort or the Synod of Dort, but would lash out at hyper-Calvinism, then you know that something is seriously wrong within the camp. -

Whitney, Donald S

BENJAMIN KEACH’S DOCTRINE OF THE HUMAN WILL Introduction The nature and freedom of the human will has been deliberated and debated throughout the history of the Christian church by some of the church’s best and most gifted theologians, and it continues to be debated to this very day. It is one of those vital theological issues that serves as a touchstone of the rest of a theological system because it both shapes and is shaped by the whole body of doctrine articulated in a full-orbed and consistent biblical theology. Because it occupies such a prominent and central place in the matrix of any theology, the question of the nature and freedom of the will is never established or articulated in an historical or theological vacuum, but inevitably and always in light of the progress of the church’s historical discussion and understanding of the nature of the will and the interconnection and unity of truths that compose any particular theological system. Benjamin Keach’s theology of the will reflects this reality inasmuch as it was articulated in light of the church’s biblical theological understanding of his own time and was vitally related to the rest of his biblical theology. For his part, Keach stood squarely in the Reformed tradition, and held to the Calvinistic doctrine of the nature and freedom of the will. It was this Calvinistic perspective which he argued and defended so forcefully and consistently throughout his published material. For Keach, the doctrine of the will was not simply a matter of philosophical speculation or a secondary matter of theology, but instead, it was something integral and foundational to the gospel itself. -

Church and People in Interregnum Britain

Downloaded from the Humanities Digital Library http://www.humanities-digital-library.org Open Access books made available by the School of Advanced Study, University of London Press ***** Publication details: Church and People in Interregnum Britain Edited by Fiona McCall https://humanities-digital-library.org/index.php/hdl/catalog/book/ church-and-people-in-interregnum-britain DOI: 10.14296/2106.9781912702664 ***** This edition published in 2021 by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PRESS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU, United Kingdom ISBN 978-1-912702-66-4 (PDF edition) This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses Church and people in interregnum Britain New Historical Perspectives is a book series for early career scholars within the UK and the Republic of Ireland. Books in the series are overseen by an expert editorial board to ensure the highest standards of peer-reviewed scholarship. Commissioning and editing is undertaken by the Royal Historical Society, and the series is published under the imprint of the Institute of Historical Research by the University of London Press. The series is supported by the Economic History Society and the Past and Present Society. Series co-editors: Heather Shore (Manchester Metropolitan University) and Elizabeth Hurren (University of Leicester) Founding co-editors: Simon Newman (University -

The Beginnings of the Library in Charles Town, South Carolina by Edgae Legake Pennington

1934.] The Library in Charles Town, So. Carolina 159 THE BEGINNINGS OF THE LIBRARY IN CHARLES TOWN, SOUTH CAROLINA BY EDGAE LEGAKE PENNINGTON HE lending library of colonial America owes most to T the industry and example of an English clergy- man, the Reverend Doctor Thomas Bray. Bray was born at Marton in Shropshire in 1656; after studying divinity at Oxford, he entered holy orders. He early attracted attention by his indefatigable zeal and great industry, and his interest in various reform movements. His energies led to his selection as a proper person to model the infant Church of England in the province of Maryland and establish it on a solid foundation. There had been a petition from that province for the assist- ance of a "superintendent, commissary, or suffragan"; 80, in April, 1696, Thomas Bray was appointed com- missary, or official representative of the Bishop of London who acted as diocesan of the Church in the American colonies. Bray was not able to go promptly. As he was impressed by the fact that it was difficult to secure the best ministers for the colonial field, he began to direct his efforts towards remedying such difficulties as might stand in the way. He found that the clergymen were usually too poor to buy books; and across the sea, shut off from educational opportunities, they must needs deteriorate. He laid the results of his enquiries before the bishops ; and declared that without a compe- tent provision of reading matter, the ministers could not prove useful to the design of their mission, and that a library would be the best encouragement to studious and sober men to enter the service. -

April 2016 Issue of the Protestant Re- Formed Theological Journal

Editor’s Notes You hold in your hand the April 2016 issue of the Protestant Re- formed Theological Journal. Included in this issue are three articles and a number of book reviews, some of them rather extensive. We are confident that you will find the contents of this issue worth the time you spend in reading—well worth the time. Few doctrines of the faith are more precious to the Reformed be- liever than the doctrine of God’s everlasting covenant of grace. Few books of the Bible are dearer to the saints than the book of Psalms. Prof. Dykstra puts those two together in the first of two articles on “God’s Covenant of Grace in the Psalms.” You will find his article both instructive and edifying. The Reverend Joshua Engelsma, pastor of the Protestant Reformed Church in Doon, Iowa contributes a very worthwhile article on Jo- hannes Bogerman. Bogerman was the man chosen to be president of the great Synod of Dordt, 1618-’19. The article not only traces the life and public ministry of Bogerman, but demonstrates clearly the direct influence that he had on the formulation of the articles in the First Head of doctrine in the Canons of Dordt. This is an especially appropriate article as the Reformed churches around the world prepare to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the Synod of Dordt in 2018-’19. The Protestant Reformed Seminary is planning to hold a conference to commemorate this very significant anniversary. We will keep our readers informed of the specifics of the conference as they are arranged. -

Langley Sbts 0207D 10640.Pdf (1.245Mb)

Copyright © 2020 Stuart Benjamin Langley All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. WHO SAYS THAT GOD LOVES THE WORLD? A HISTORICAL ARGUMENT TO IDENTIFY THE AMBIGUOUS SPEAKERS IN JOHN 3 __________________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________ by Stuart Benjamin Langley December 2020 APPROVAL SHEET WHO SAYS THAT GOD LOVES THE WORLD? A HISTORICAL ARGUMENT TO IDENTIFY THE AMBIGUOUS SPEAKERS IN JOHN 3 Stuart Benjamin Langley Read and Approved by: ________________________________________ Jonathan T. Pennington (Chair) ________________________________________ William F. Cook III ________________________________________ Brian J. Vickers Date______________________________ ἐκεῖνον δεῖ αὐξάνειν, ἐμὲ δὲ ἐλαττοῦσθ TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................... vii LIST OF TABLES……………………………………………………………………. ...xii PREFACE ......................................................................................................................... xii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................1 Thesis ..................................................................................................................3 -

'Dimittimini, Exite'

Seite 1 von 13 ‘Dimittimini, exite’ Debating Civil and Ecclesiastical Power in the Dutch Republic 1. Dordrecht, Monday 14 January 1619. ‘You are cast away, go! You have started with lies, you have ended with lies. Dimittimini, exite’. The end was bitter and dramatic. The chairman of the Synod of Dort, Johannes Bogerman, lost his patience. Roaring, as some reports put it, he ordered Simon Episcopius, who had just, in equally outspoken terms, accused Bogerman of committing acts of slavery, to leave. Episcopius and his fellow Arminians left. As usual the two great --indeed massive-- seventeenth century accounts of the Synod, those of Johannes Uytenbogaert on the Arminian and of Jacobus Trigland on the orthodox Calvinist side, differ strongly in their account and appreciation of what happened at the Synod of Dort1. But they agreed Dort marked a schism; Dutch Reformed Protestantism had split apart. In almost all 57 fateful sessions of the synod which had started on 13 November 1618 the debate had been bitter, though invariably participants asked for moderation, temperance and sobriety. The Synod vacillated between the bitterness of intense theological dispute and a longing for religious peace, between the relentless quest for truth and the thirst for toleration. For over ten years Dutch Reformed Protestants had been arguing, with increasing intensity and rancour. Divisions and issues were manifold with those, such as Simon 1 See Johannes Uytenbogaert, Kerckelicke Historie, Rotterdam, 1647, pp. 1135-1136 and Jacobus Trigland, Kerckelycke Geschiedenissen, begrypende de swaere en Bekommerlijcke Geschillen, in de Vereenigde Nederlanden voorgevallen met derselver Beslissinge, Leiden, 1650, p 1137. -

Ships of Church and State in the Sixteenth-Century Reformation and Counterreformation: Setting Sail for the Modern State

MWP – 2014/05 Max Weber Programme Ships of Church and State in the Sixteenth-Century Reformation and Counterreformation: Setting Sail for the Modern State AuthorStephan Author Leibfried and and Author Wolfgang Author Winter European University Institute Max Weber Programme Ships of Church and State in the Sixteenth-Century Reformation and Counterreformation: Setting Sail for the Modern State Stephan Leibfried and Wolfgang Winter Max Weber Lecture No. 2014/05 This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper or other series, the year, and the publisher. ISSN 1830-7736 © Stephan Leibfried and Wolfgang Winter, 2014 Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Abstract Depictions of ships of church and state have a long-standing religious and political tradition. Noah’s Ark or the Barque of St. Peter represent the community of the saved and redeemed. However, since Plato at least, the ship also symbolizes the Greek polis and later the Roman Empire. From the fourth century ‒ the Constantinian era ‒ on, these traditions merged. Christianity was made the state religion. Over the course of a millennium, church and state united in a religiously homogeneous, yet not always harmonious, Corpus Christianum. In the sixteenth century, the Reformation led to disenchantment with the sacred character of both church and state as mediators indispensible for religious and secular salvation.