Eugenio Pacelli: His Diplomacy Prior to His Pontificate and Its Lingering Results

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uneeveningseveralyearsago

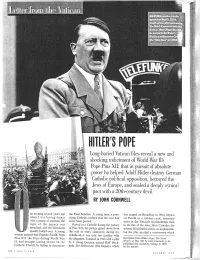

SUdfffiiUeraiKdiesavadio speechfinWay9,3934, »eariya3fearjafierannounce !Uie9leich£oncoRlati^3he Vatican.Aisei^flope^us )isseamed^SLIRetef^ Sa^caonVeconber ahe*»otyireaf'4Dfl9ra: 'i ' TlfraR Long-buried Vatican files reveal a new anc ; shocking indictment of World War IPs Jj; : - I • • H.t.-,. in n. ; Pope Pius XII: that in pursuit of absolute power he helped Adolf Hitler destroy German ^ Catholic political opposition, betrayed the Europe, and sealed a deeply cynica pact with a 20th-century devi!. BBI BY JOHN CORNWELL the Final Solution. A young man, a prac was staged on Broadway in 1964. depict UnewheneveningI wasseveralhavingyearsdinnerago ticing Catholic, insisted that the case had ed Pacelli as a ruthless cynic, interested with a group of students, the never been proved. more in the Vatican's stockholdings than topic of the papacy was Raised as a Catholicduring the papacy in the fate of the Jews. Most Catholics dis broached, and the discussion of Pius XII—his picture gazed down from missed Hochhuth's thesis as implausible, quickly boiled over. A young the wall of every classroom during my but the play sparked a controversy which woman asserted that Eugenio Pacelli, Pope childhood—I was only too familiar with Pius XII, the Pope during World War the allegation. It started in 1963 with a play Excerpted from Hitler's Pope: TheSeci-et II, had brought lasting shame on the by a young German named Rolf Hoch- History ofPius XII. bj' John Comwell. to be published this month byViking; © 1999 Catholic Church by failing to denounce huth. DerStellverti-eter (The Deputy), which by the author. VANITY FAIR OCTOBER 1999 having reliable knowl- i edge of its true extent. -

Katholisches Wort in Die Zeit 45. Jahr März 2014

Prof. Dr. Konrad Löw: Pius XII.: „Bleibt dem katholischen Glauben treu!“ 68 Gerhard Stumpf: Reformer und Wegbereiter in der Kirche: Klemens Maria Hofbauer 76 Franz Salzmacher: Europa am Scheideweg 82 Katholisches Wort in die Zeit 45. Jahr März 2014 DER FELS 3/2014 65 Formen von Sexualität gleich- Liebe Leser, wertig sind. Eine Vorgeschichte hat weiterhin die Insolvenz des kircheneigenen Unternehmens der Karneval ist in der katho- „Weltbild“. Das wirtschaftliche lischen Welt zuhause, wo sich Desaster ist darauf zurückzufüh- der Rhythmus des Lebens auch ren, dass die Geschäftsführung im Kirchenjahr widerspiegelt. zu spät auf das digitale Geschäft Die Kirche kennt eben die Natur gesetzt hat. Hinzu kommt die INHALT des Menschen und weiß, dass er Sortimentsausrichtung, die mit auch Freude am Leben braucht. Esoterik, Pornographie und sa- tanistischer Literatur, trotz vie- Papst Franziskus: Lebensfreude ist nicht gera- Das Licht Christi in tiefster Finsternis ....67 de ein Zeichen, das unsere Zeit ler Hinweise über Jahrzehnte, charakterisiert. Die zunehmen- keineswegs den Anforderungen Prof. Dr. Konrad Löw: : den psychischen Erkrankungen eines kircheneigenen Medien- Pius XII.: „Bleibt dem sprechen jedenfalls nicht dafür. unternehmens entsprach. Eine katholischen Glauben treu!“ .................68 „Schwermut ist die Signatur der Vorgeschichte hat schließlich die Gegenwart geworden“, lautet geistige Ausrichtung des ZDK Raymund Fobes: der Titel eines Artikels, der die- und der sie tragenden Großver- Seid das Salz der Erde ........................72 ser Frage nachgeht (Tagespost, bände wie BDKJ, katholische 1.2.14). Frauenverbände etc. Prälat Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Lothar Roos: Die Menschen erleben heute, Die selbsternannten „Refor- „Ein Licht für das Leben mer“ der deutschen Ortskirche in der Gesellschaft“ (Lumen fidei) .........74 dass sie mit verdrängten Prob- lemen immer mehr in Tuchfüh- ereifern sich immer wieder ge- Gerhard Stumpf: lung kommen. -

Pius XII on Trial

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2014 Pius XII on Trial Katherine M. Campbell University of Maine - Main, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Katherine M., "Pius XII on Trial" (2014). Honors College. 159. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/159 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PIUS XII ON TRIAL by Katherine M. Campbell A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology and Political Science) The Honors College University of Maine May 2014 Advisory Committee: Henry Munson, Professor of Anthropology Alexander Grab, Professor of History Mark D. Brewer, Associate Professor of Political Science Richard J. Powell, Associate Professor of Political Science, Leadership Studies Sol Goldman, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Political Science Copyright 2014 Katherine M. Campbell Abstract: Scholars have debated Pope Pius XII’s role in the Holocaust since the 1960s. Did he do everything he could and should have done to save Jews? His critics say no because of antisemitism rooted in the traditional Catholic views. His defenders say yes and deny that he was an antisemite. In my thesis, I shall assess the arguments on both sides in terms of the available evidence. I shall focus both on what Pius XII did do and what he did not do and on the degree to which he can be held responsible for the actions of low-level clergy. -

The Armenian Cause in America Today

THE ARMENIAN CAUSE IN AMERICA TODAY While meager Turkish American NGO assets are dedicated to cultural events and providing education on a wide range of political issues, approximately $40 million in Armenian American NGO assets are primarily dedicated to what is referred to in Armenian as Hai Tahd, ‘The Armenian Cause’. Hai Tahd includes three policy objectives: Recognition that the 1885-1919 Armenian tragedy constitutes genocide; Reparations from Turkey; and, Restitution of the eastern provinces of Turkey to Armenia. This paper examines the Armenian American strategy and the response of Turkish American via the Assembly of Turkish American Associations (ATAA). Günay Evinch Gunay Evinch (Övünç) practices international public law at Saltzman & Evinch and serves as Assembly of Turkish American Associations (ATAA) Vice-President for the Capital Region. He researched the Armenian case in Turkey as a U.S. Congressional Fulbright Scholar and Japan Sasakawa Peace Foundation Scholar in international law in 1991-93. To view media coverage and photographs associated with this article, please see, Günay Evinch, “The Armenian Cause Today,” The Turkish American, Vol. 2, No. 8 (Summer 2005), pp. 22-29. Also viewable at www.ATAA.org The Ottoman Armenian tragedy of 1880-1919 is a dark episode in the history of Turkish and Armenian relations. Over one million Muslims, mostly Kurds, Turks, and Arabs, and almost 600,000 Armenians perished in eastern Anatolia alone. WWI took the lives of 10 million combatants and 50 million civilians. While Russia suffered the greatest population deficit, the Ottoman Empire lost over five million, of which nearly 4 million were Muslims, 600,000 were Armenian, 300,000 were Greek, and 100,000 were Ottoman Jews.1 Moreover, the millennial Armenian presence in eastern Anatolia ended. -

The Historical Journal VIA RASELLA, 1944

The Historical Journal http://journals.cambridge.org/HIS Additional services for The Historical Journal: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here VIA RASELLA, 1944: MEMORY, TRUTH, AND HISTORY JOHN FOOT The Historical Journal / Volume 43 / Issue 04 / December 2000, pp 1173 1181 DOI: null, Published online: 06 March 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0018246X00001400 How to cite this article: JOHN FOOT (2000). VIA RASELLA, 1944: MEMORY, TRUTH, AND HISTORY. The Historical Journal, 43, pp 11731181 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/HIS, IP address: 144.82.107.39 on 26 Sep 2012 The Historical Journal, , (), pp. – Printed in the United Kingdom # Cambridge University Press REVIEW ARTICLE VIA RASELLA, 1944: MEMORY, TRUTH, AND HISTORY L’ordine eZ giaZ stato eseguito: Roma, le Fosse Ardeatine, la memoria. By Alessandro Portelli. Rome: Donzelli, . Pp. viij. ISBN ---.L... The battle of Valle Giulia: oral history and the art of dialogue. By A. Portelli. Wisconsin: Wisconsin: University Press, . Pp. xxj. ISBN ---.$.. [Inc.‘The massacre at Civitella Val di Chiana (Tuscany, June , ): Myth and politics, mourning and common sense’, in The Battle of Valle Giulia, by A. Portelli, pp. –.] Operazione Via Rasella: veritaZ e menzogna: i protagonisti raccontano. By Rosario Bentivegna (in collaboration with Cesare De Simone). Rome: Riuniti, . Pp. ISBN -- -.L... La memoria divisa. By Giovanni Contini. Milan: Rizzoli, . Pp. ISBN -- -.L... Anatomia di un massacro: controversia sopra una strage tedesca. By Paolo Pezzino. Bologna: Il Mulino, . Pp. ISBN ---.L... Processo Priebke: Le testimonianze, il memoriale. Edited by Cinzia Dal Maso. -

Kornberg on Godman, 'Hitler and the Vatican: Inside the Secret Archives That Reveal the New Story of the Nazis and the Church'

H-German Kornberg on Godman, 'Hitler and the Vatican: Inside the Secret Archives that Reveal the New Story of the Nazis and the Church' Review published on Saturday, October 1, 2005 Peter Godman. Hitler and the Vatican: Inside the Secret Archives that Reveal the New Story of the Nazis and the Church. New York: Free Press, 2004. xvi + 282 pp. $27.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-7432-4597-5. Reviewed by Jacques Kornberg (Department of History, University of Toronto)Published on H- German (October, 2005) The Vatican and National Socialism: Between Criticism and Conciliation Peter Godman of the University of Rome, a scholar who has studied the Catholic Church, was one of the first people granted permission to mine the recently opened archives of the Supreme Congregation of the Holy Office for the pontificate of Pius XI (1922-39). In keeping with the times, the Holy Office currently bears the less forbidding name of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith; it was once known as the Universal Inquisition. Headed by bishops and cardinals, the Congregation pronounces on doctrine in matters of faith and morals. Godman contrasts his own "behind the scenes" view based on a close reading of the Holy Office documents, with the "hot air of speculation" hanging over the works of John Cornwell and Daniel Goldhagen. There is some truth to his claim, but he sets expectations too high when he professes to open a window into "the thoughts and motives" of those who made policy (p. xv). All we have of Pius XI and his Secretary of State, Cardinal Pacelli, are office memos, public statements, protocols of meetings, reports of papal audiences, and letters to bishops; we will always have to stake out some educated guesses about their thoughts and motives. -

American Catholicism and the Political Origins of the Cold War/ Thomas M

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1991 American Catholicism and the political origins of the Cold War/ Thomas M. Moriarty University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Moriarty, Thomas M., "American Catholicism and the political origins of the Cold War/" (1991). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1812. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1812 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICAN CATHOLICISM AND THE POLITICAL ORIGINS OF THE COLD WAR A Thesis Presented by THOMAS M. MORI ARTY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 1991 Department of History AMERICAN CATHOLICISM AND THE POLITICAL ORIGINS OF THE COLD WAR A Thesis Presented by THOMAS M. MORIARTY Approved as to style and content by Loren Baritz, Chair Milton Cantor, Member Bruce Laurie, Member Robert Jones, Department Head Department of History TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. "SATAN AND LUCIFER 2. "HE HASN'T TALKED ABOUT ANYTHING BUT RELIGIOUS FREEDOM" 25 3. "MARX AMONG THE AZTECS" 37 4. A COMMUNIST IN WASHINGTON'S CHAIR 48 5. "...THE LOSS OF EVERY CATHOLIC VOTE..." 72 6. PAPA ANGEL I CUS 88 7. "NOW COMES THIS RUSSIAN DIVERSION" 102 8. "THE DEVIL IS A COMMUNIST" 112 9. -

Le Leggi Razziali E La Persecuzione Degli Ebrei a Roma 1938-1945

I QUADERNI DI MUMELOC · 1 · MUSEO DELLA MEMORIA LOCALE DI CERRETO GUIDI Coordinamento editoriale Marco Folin In copertina: telegramma con cui il ministro dell’Interno invita i prefetti a inasprire la politica razziale contro gli ebrei, 1941 (ASROMA, Prefettura, Gabinetto, b. 1515). ISBN 000-000-00-0000-000-0 © 2012 Museo della Memoria Locale di Cerreto Guidi Piazza Dante Desideri - 50050 Cerreto Guidi (FI) www.mumeloc.it © 2012 Archivio Storico della Comunità Ebraica di Roma Lungotevere Cenci (Tempio), 00186 Roma www.romaebraica.it/archivio-storico-ascer/ Le leggi razziali e la persecuzione degli ebrei a Roma 1938-1945 a cura di Silvia Haia Antonucci, Pierina Ferrara, Marco Folin e Manola Ida Venzo ARCHIVIO DI STATO DI ROMA Questo libro è dedicato alla memoria di Eugenio Sonnino Il Signore riconosce la strada dei giusti, mentre la via degli empi si perde (Salmo I, 6) Le leggi razziali e la persecuzione degli ebrei a Roma, 1938-1945 A cura di S.H. Antonucci, P. Ferrara, M. Folin e M.I. Venzo 9 Il MuMeLoc e la Comunità Ebraica romana: le ragioni di una mostra, di Marco Folin 13 Il percorso espositivo allestito nel MuMeLoc, di Pierina Ferrara 15 La mostra e il suo percorso, di Manola Ida Venzo 21 CATALOGO 23 Il fascismo e le leggi razziali, di Manola Ida Venzo 45 Le scuole per i giovani ebrei di Roma negli anni delle Leggi per la difesa della razza (1938-1944), di Giuliana Piperno Beer 55 Gli ebrei romani dall'emancipazione alle Leggi razziali. Aspetti economici e sociali, di Claudio Procaccia 65 La deportazione a Roma, di Giancarlo Spizzichino 99 STUDI 101 La propaganda antisemita nel fascismo. -

HISTORY 319—THE VIETNAM WARS Fall 2017 Mr

University of Wisconsin–Madison Department of History HISTORY 319—THE VIETNAM WARS Fall 2017 Mr. McCoy I. COURSE PROCEDURES: Class Meetings: Lectures are given in 1111 Humanities by Mr. McCoy on Tuesdays and Thursdays, from 4:00 to 5:15 p.m. In addition, students will attend a one-hour discussion section each week conducted by the Teaching Assistant (TA) for this course. N.B. Laptops may used only for taking notes and may not be used to access the Internet. Office Hours: —For Marlana Margaria, Humanities Room 4274, on Tuesdays from 1:45 to 3:45 p.m. and other hours by appointment (TEL: 265-9480). Messages may be left in Humanities Mailbox No. 4041, or sent via e-mail to: <[email protected]> —For Alfred McCoy, Humanities Room 5131, Thursdays 12:00 to 2:00 p.m. and other hours by appointment (TEL: 263-1855). Messages may be left in Humanities Mailbox No. 5026, or sent via e-mail to: <[email protected]> Grading: Students shall complete three pieces of written work. On October 19, students shall take a midterm examination. On November 21, students shall submit a 5,000-word research essay with full footnotes and bibliographic references. During examination week on December 16, students shall take a two-hour final examination. Final grades shall be computed as follows: —midterm take-home exam: 20% —research essay: 30% —discussion section mark: 30% —final examination: 20% —extra credit/film viewing: 3% Course Requirements: For each of these assignments, there are different requirements for both the amount and form of work to be done: a.) Midterm take-home examination: Select two questions from a list distributed in the lecture on Thursday, October 19, and turn in two short essays totaling five typed pages, with full endnote citations, at the start of class on Tuesday, October 24. -

The Holy See

The Holy See ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS POPE FRANCIS TO MEMBERS OF THE DELEGATION OF THE "CONFERENCE OF EUROPEAN RABBIS" Monday, 20 April 2015 [Multimedia] Dear Friends, I welcome you, members of the delegation of the Conference of European Rabbis, to the Vatican. I am especially pleased to do so, as this is the first visit by your Organization to Rome to meet with the Successor of Peter. I greet your President, Rabbi Pinchas Goldschmidt, and I thank him for his kind words. I wish to express my sincere condolences for the death last evening of Rabbi Elio Toaff, former Chief Rabbi of Rome. I am united in prayer with Chief Rabbi Riccardo Di Segni – who would have been here with us – and with the entire Jewish Community in Rome. We gratefully remember this man of peace and dialogue who received Pope John Paul II during his historic visit to the Great Synagogue of Rome. For almost fifty years, the dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Jewish community has progressed in a systematic way. Next 28 October we will celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the conciliar Declaration Nostra Aetate, which is still the reference point for every effort we make in this regard. With gratitude to the Lord, may we recall these years, rejoicing in our progress and in the friendship which has grown between us. Today, in Europe, it is more important than ever to emphasise the spiritual and religious dimension of human life. In a society increasingly marked by secularism and threatened by atheism, we run the risk of living as if God did not exist. -

Distributism Debate

The Distributism Debate The Distributism Debate Dane J. Weber Donald P. Goodman III Eds. GP Goretti Publications Dozenal numeration is a system of thinking of numbers in twelves, rather than tens. Twelve is much more versatile, having four even divisors—2, 3, 4, and 6—as opposed to only two for ten. This means that such hatefulness as “0.333. ” for 1/3 and “0.1666. ” for 1/6 are things of the past, replaced by easy “0;4” (four twelfths) and “0;2” (two twelfths). In dozenal, counting goes “one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, elv, dozen; dozen one, dozen two, dozen three, dozen four, dozen five, dozen six, dozen seven, dozen eight, dozen nine, dozen ten, dozen elv, two dozen, two dozen one. ” It’s written as such: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X, E, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 1X, 1E, 20, 21... Dozenal counting is at once much more efficient and much easier than decimal counting, and takes only a little bit of time to get used to. Further information can be had from the dozenal societies (http:// www.dozenal.org), as well as in many other places on the Internet. © 2006 (11E2) Dane J. Weber and Donald P. Goodman III, Version 3.0. All rights reserved. This document may be copied and distributed freely, provided that it is done in its entirety, including this copyright page, and is not modified in any way. Goretti Publications http://gorpub.freeshell.org [email protected] No copyright on this work is intended to in any way derogate from the copyright holders of any individual part of this work. -

SAMPLE His Priests from Ever Entering a Synagogue.” I Was Amazed and Crushed

Introduction Gilbert S. Rosenthal I was a young and callow rabbi serving a congregation in New Jersey about forty miles from New York City. The year was 1960, and Thanks- giving was approaching. I had an inspirational idea: My synagogue was literally across the road from a Roman Catholic church. Why not invite the priest and his flock to join my congregation in a program—not a wor- ship service—of thanksgiving for the blessings of freedom in this blessed land? So I called the priest whom I had never met and enthusiastically told him of my idea, stressing that this would be a program without any liturgical content, confident that he would accept my invitation. I was quite wrong: The priest responded, “Rabbi, I should very much like to take you up on your offer but I cannot. You see, my bishop, Bishop Ahr of Trenton, prohibitsSAMPLE his priests from ever entering a synagogue.” I was amazed and crushed. The fact that I vividly remember that conversation after over fifty years have elapsed underscores my sense of despair and the lasting impression it made on me. Imagine that a scant fifteen years after the Shoah—the Holocaust that destroyed six million Jews in Christian Europe—and the Catholic Church would not even talk to Jews or enter their houses of worship! We were just across the road from each other, but we might as well have been on other sides of the world. Perhaps that episode was the catalyst of my commitment to interreligious dialogue throughout my long rabbinic career.