Demarcation of the DRC-Zambia Boundary from 1894 to the Present Day

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zambia 30 September 2017

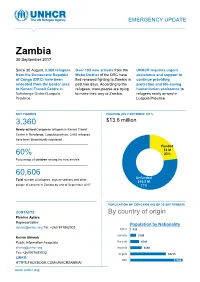

EMERGENCY UPDATE Zambia 30 September 2017 Since 30 August, 3,360 refugees Over 100 new arrivals from the UNHCR requires urgent from the Democratic Republic Moba District of the DRC have assistance and support to of Congo (DRC) have been fled renewed fighting to Zambia in continue providing relocated from the border area past two days. According to the protection and life-saving to Kenani Transit Centre in refugees, more people are trying humanitarian assistance to Nchelenge District/Luapula to make their way to Zambia. refugees newly arrived in Province. Luapula Province. KEY FIGURES FUNDING (AS 2 OCTOBER 2017) 3,360 $13.6 million requested for Zambia operation Newly-arrived Congolese refugees in Kenani Transit Centre in Nchelenge, Luapula province. 2,063 refugees have been biometrically registered Funded $3 M 60% 23% Percentage of children among the new arrivals Unfunded XX% 60,606 [Figure] M Unfunded Total number of refugees, asylum-seekers and other $10.5 M people of concern in Zambia by end of September 2017 77% POPULATION OF CONCERN (AS OF 30 SEPTEMBER) CONTACTS By country of origin Pierrine Aylara Representative Population by Nationality [email protected] Tel: +260 977862002 Other 415 Somalia 3199 Kelvin Shimoh Public Information Associate Burundi 4749 [email protected] Rwanda 6130 Tel: +260979585832 Angola 18715 LINKS: DRC 27398 HTTPS:FACEBOOK.COM/UNHCRZAMBIA/ www.unhcr.org 1 EMERGENCY UPDATE > Zambia / 30 September 2017 Emergency Response Luapula province, northern Zambia Since 30 August, over 3,000 asylum-seekers from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have crossed into northern Zambia. New arrivals are reportedly fleeing insecurity and clashes between Congolese security forces FARDC and a local militia groups in towns of Pweto, Manono, Mitwaba (Haut Katanga Province) as well as in Moba and Kalemie (Tanganyika Province). -

ZAMBIA HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT 1 January to 30 June 2018

UNICEF ZAMBIA HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT 1 January to 30 June 2018 Zambia Humanitarian Situation Report ©UNICEF Zambia/2017/Ayisi ©UNICEF REPORTING PERIOD: JANUARY - JUNE 2018 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 15,425 # of registered refugees in Nchelengue • As of 28 June 2018, a total of 15,425 refugees from the district Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) were registered at (UNHCR, Infographic 28 June 2018) Kenani transit centre in the Luapula Province of Zambia. • UNICEF and partners are supporting the Government of Zambia 79% to provide life-saving services for all the refugees in Kenani of registered refugees are women and transit centre and in the Mantapala permanent settlement area. children • More than half of the refugees have been relocated to Mantapala permanent settlement area. 25,000 • The set-up of basic services in Mantapala is drastically delayed # of expected new refugees from DRC in due to heavy rainfall that has made access roads impassable. Nchelengue District in 2018 • Discussions between UNICEF and the Government are under way to develop a transition and sustainability plan to ensure the US$ 8.8 million continuity of services in refugee hosting areas. UNICEF funding requirement UNICEF’s Response with Partners Funding Status 2018 UNICEF Sector Carry- forward Total Total amount: UNICEF Sector $0.2 m Funds received current Target Results* Target year: $2.5 m Results* Nutrition: # of children admitted for SAM 400 273 400 273 treatment Health: # of children vaccinated against 11,875 6,690 11,875 6,690 measles WASH: # of people provided with access to 15,000 9,253 25,000 15,425 Funding Gap: $6.1 m safe water =68% Child Protection: # of children receiving 5,500 3,657 9,000 4,668 psychosocial and/or other protection services Funds available include funding received for the current year as well as the carry-forward from the previous year. -

The Coincidence of Ecological Opportunity with Hybridization Explains Rapid Adaptive Radiation in Lake Mweru Cichlid fishes

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13278-z OPEN The coincidence of ecological opportunity with hybridization explains rapid adaptive radiation in Lake Mweru cichlid fishes Joana I. Meier 1,2,3,4, Rike B. Stelkens 1,2,5, Domino A. Joyce 6, Salome Mwaiko 1,2, Numel Phiri7, Ulrich K. Schliewen8, Oliver M. Selz 1,2, Catherine E. Wagner 1,2,9, Cyprian Katongo7 & Ole Seehausen 1,2* 1234567890():,; The process of adaptive radiation was classically hypothesized to require isolation of a lineage from its source (no gene flow) and from related species (no competition). Alternatively, hybridization between species may generate genetic variation that facilitates adaptive radiation. Here we study haplochromine cichlid assemblages in two African Great Lakes to test these hypotheses. Greater biotic isolation (fewer lineages) predicts fewer constraints by competition and hence more ecological opportunity in Lake Bangweulu, whereas opportunity for hybridization predicts increased genetic potential in Lake Mweru. In Lake Bangweulu, we find no evidence for hybridization but also no adaptive radiation. We show that the Bangweulu lineages also colonized Lake Mweru, where they hybridized with Congolese lineages and then underwent multiple adaptive radiations that are strikingly complementary in ecology and morphology. Our data suggest that the presence of several related lineages does not necessarily prevent adaptive radiation, although it constrains the trajectories of morphological diversification. It might instead facilitate adaptive radiation when hybridization generates genetic variation, without which radiation may start much later, progress more slowly or never occur. 1 Division of Aquatic Ecology & Evolution, Institute of Ecology and Evolution,UniversityofBern,Baltzerstr.6,CH-3012Bern,Switzerland.2 Department of Fish Ecology and Evolution, Centre of Ecology, Evolution and Biogeochemistry (CEEB), Eawag Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, Seestrasse 79, CH-6047 Kastanienbaum, Switzerland. -

Somali Fisheries

www.securefisheries.org SECURING SOMALI FISHERIES Sarah M. Glaser Paige M. Roberts Robert H. Mazurek Kaija J. Hurlburt Liza Kane-Hartnett Securing Somali Fisheries | i SECURING SOMALI FISHERIES Sarah M. Glaser Paige M. Roberts Robert H. Mazurek Kaija J. Hurlburt Liza Kane-Hartnett Contributors: Ashley Wilson, Timothy Davies, and Robert Arthur (MRAG, London) Graphics: Timothy Schommer and Andrea Jovanovic Please send comments and questions to: Sarah M. Glaser, PhD Research Associate, Secure Fisheries One Earth Future Foundation +1 720 214 4425 [email protected] Please cite this document as: Glaser SM, Roberts PM, Mazurek RH, Hurlburt KJ, and Kane-Hartnett L (2015) Securing Somali Fisheries. Denver, CO: One Earth Future Foundation. DOI: 10.18289/OEF.2015.001 Secure Fisheries is a program of the One Earth Future Foundation Cover Photo: Shakila Sadik Hashim at Alla Aamin fishing company in Berbera, Jean-Pierre Larroque. ii | Securing Somali Fisheries TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES, TABLES, BOXES ............................................................................................. iii FOUNDER’S LETTER .................................................................................................................... v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. vi DEDICATION ............................................................................................................................ vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (Somali) ............................................................................................ -

Download: Africa

TUNISIA MOROCCO ALGERIA LIBYA Western EGYPT Sahara MAURITANIA MALI NIGER ERITREA SENEGAL THE GAMBIA CHAD SUDAN GUINEA-BISSAU BURKINA DJIBOUTI FASO GUINEA BENIN NIGERIA SIERRA TOGO ETHIOPIA LEONE CÔTE CENTRAL D’IVOIRE GHANA LIBERIA AFRICAN REP. CAMEROON SOMALIA UGANDA SAO TOME EQUAT. AND PRINCIPE GUINEA REP. OF KENYA GABON THE CONGO RWANDA DEM. REP. BURUNDI OF THE CONGO INDIAN TANZANIA OCEAN ANGOLA MALAWI ATL ANTIC ZAMBIA OCEAN MOZAMBIQUE ZIMBABWE MADAGASCAR NAMIBIA BOTSWANA SWAZILAND LESOTHO SOUTH AFRICA Africa Rahnuma Hassan, Anna Horvai, Paige Jennings, Bobbie Mellor and George Mukundi Wachira publicized findings regarding the practice of human trafficking, including of women and girls, within Central and through the region, while others drew attention to the effects of drug trafficking. The treatment of asylum-seekers and refugees, many of whom may and West belong to minorities in their countries of origin, was also a serious concern. In one example, in July a joint operation between the governments Africa of Uganda and Rwanda saw the forced return of around 1,700 Rwandans from refugee settlements Paige Jennings in south-western Uganda. Armed police officers reportedly surrounded them and forced them onto he year 2010 marked 50 years of inde- waiting trucks, which proceeded to drop them at a pendence for many countries in Africa. transit centre in Rwanda. The United Nations High T Elections, some unprecedented, were Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) protested held in 22 countries, with others planned for 2011. at the failure to respect international standards While elections can be a positive indicator of the and reported that not only asylum-seekers but also level of respect for fundamental freedoms, the recognized refugees were among those forcibly region offered several examples of how electoral con- returned to their country of origin. -

Report20 Uniting to End Malaria 501(C)3

PHOTO BY PAUL ISHII ANNUAL REPORT20 Uniting to End Malaria 501(c)3. EIN: 46-1380419 No one can foresee the duration or severity of COVID’s human and economic toll. But the malaria global health community agrees it will be disastrous to neglect or underinvest in malaria during this period, and thereby squander a decade of hard won progress. By some estimates, halting malaria intervention efforts could trigger a return to one million malaria deaths per year, a devastating mortality rate unseen since 2004. To that end many of our efforts last year were to strategically advocate for continued global malaria funding, as well as supporting COVID adjustments to ensure malaria projects were not delayed. Last year we supplied Personal Protection Equipment (PPE) to over 700 Rotary-funded community health workers (CHWs) in Uganda and Zambia; altered CHW The training to incorporate appropriate social distancing; conducted several webinars specifically focused on maintaining malaria financial support despite COVID; and we provided $50,000 to the Alliance for Malaria Prevention used for COVID/malaria public education in Africa. Jeff Pritchard Board Chair While our near-term work must accommodate pandemic restrictions, we are still firmly committed to our mission, “to generate a broad international Rotary campaign for the global elimination of malaria.” During the coming twelve months we intend to: • Implement a blueprint developed in 2020 for a large long-term Road malaria program with Rotary, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and World Vision, in the most underserved regions of Zambia’s Central and Muchinga Provinces, positively impacting nearly 1.4 million residents. -

The Political Ecology of a Small-Scale Fishery, Mweru-Luapula, Zambia

Managing inequality: the political ecology of a small-scale fishery, Mweru-Luapula, Zambia Bram Verelst1 University of Ghent, Belgium 1. Introduction Many scholars assume that most small-scale inland fishery communities represent the poorest sections of rural societies (Béné 2003). This claim is often argued through what Béné calls the "old paradigm" on poverty in inland fisheries: poverty is associated with natural factors including the ecological effects of high catch rates and exploitation levels. The view of inland fishing communities as the "poorest of the poorest" does not imply directly that fishing automatically lead to poverty, but it is linked to the nature of many inland fishing areas as a common-pool resources (CPRs) (Gordon 2005). According to this paradigm, a common and open-access property resource is incapable of sustaining increasing exploitation levels caused by horizontal effects (e.g. population pressure) and vertical intensification (e.g. technological improvement) (Brox 1990 in Jul-Larsen et al. 2003; Kapasa, Malasha and Wilson 2005). The gradual exhaustion of fisheries due to "Malthusian" overfishing was identified by H. Scott Gordon (1954) and called the "tragedy of the commons" by Hardin (1968). This influential model explains that whenever individuals use a resource in common – without any form of regulation or restriction – this will inevitably lead to its environmental degradation. This link is exemplified by the prisoner's dilemma game where individual actors, by rationally following their self-interest, will eventually deplete a shared resource, which is ultimately against the interest of each actor involved (Haller and Merten 2008; Ostrom 1990). Summarized, the model argues that the open-access nature of a fisheries resource will unavoidably lead to its overexploitation (Kraan 2011). -

Fishing Life in the Bangweulu Swamps (2): an Analysis of Catch and Seasonal Emigration of the Fishermen in Zambia

African Stud)' Monographs, Supplementary Issue 6: 33-G3, March 1987 33 Fishing Life in the Bangweulu Swamps (2): An Analysis of Catch and Seasonal Emigration of the Fishermen in Zambia. lchiro IMAI (Research Affiliate of I. A. S.) The Institute for African Studies, University of Zambia Hirosaki University. Japan ABSTRACT The aim of this paper is to describe and characterize the swamp fishing in the Bangweulu Swamps, Zambia. The fish catch by the several fishing methods are analy sed after these methods are outlined. As a result of the analysis, it is indicated that each production unit chooses a fishing method to catch a particular group of fish, such as "-1or myridae or Cichlidae fish. The types of fishing activity among the lishermen are divided into three classes in terms of their fishing seasons and methods. These types of fishing differ from each other as to how far their villages are from the swamps and what time schedules of agriculture are made according to the limits of the season or the period of fishing in the swamps. By ana lysing these types alloted to different ethnic groups, it is clarified how the swamp area is actually utilized by the several ethnic groups from different areas. I\fost of the fishermen in the Bangweulu Swamps are the part-time fishermen who are also engaged in cultivation to a considerable extent. It is discussed why these essentially agriculturalists carry on fishing for themselves without making symbiotic relationships with other fishing specialists. They can get a good cash income by selling the catch. -

Full Text Document (Pdf)

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Macola, Giacomo (2006) “It Means as If We Are Excluded from the Good Freedom”: Thwarted Expectations of Independence in the Luapula Province of Zambia, 1964-1967. Journal of African History, 47 (1). pp. 43-56. ISSN 0021-8537. DOI https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853705000848 Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/7559/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html ‘IT MEANS AS IF WE ARE EXCLUDED FROM THE GOOD FREEDOM’: THWARTED EXPECTATIONS OF INDEPENDENCE IN THE LUAPULA PROVINCE OF ZAMBIA, 1964-1966* BY GIACOMO MACOLA Centre of African Studies, University of Cambridge ABSTRACT: Based on a close reading of new archival material, this article makes a case for the adoption of an empirical, ‘sub-systemic’ approach to the study of nationalist and post- colonial politics in Zambia. -

Brazil Country Handbook 1

Brazil Country Handbook 1. This handbook provides basic reference information on Brazil, including its geography, history, government, military forces, and communications and trans- portation networks. This information is intended to familiarize military personnel with local customs and area knowledge to assist them during their assignment to Brazil. 2. This product is published under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Defense Intelligence Production Program (DoDIPP) with the Marine Corps Intel- ligence Activity designated as the community coordinator for the Country Hand- book Program. This product reflects the coordinated U.S. Defense Intelligence Community position on Brazil. 3. Dissemination and use of this publication is restricted to official military and government personnel from the United States of America, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, NATO member countries, and other countries as required and designated for support of coalition operations. 4. The photos and text reproduced herein have been extracted solely for research, comment, and information reporting, and are intended for fair use by designated personnel in their official duties, including local reproduction for train- ing. Further dissemination of copyrighted material contained in this document, to include excerpts and graphics, is strictly prohibited under Title 17, U.S. Code. CONTENTS KEY FACTS. 1 U.S. MISSION . 2 U.S. Embassy. 2 U.S. Consulates . 2 Travel Advisories. 7 Entry Requirements . 7 Passport/Visa Requirements . 7 Immunization Requirements. 7 Custom Restrictions . 7 GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE . 8 Geography . 8 Land Statistics. 8 Boundaries . 8 Border Disputes . 10 Bodies of Water. 10 Topography . 16 Cross-Country Movement. 18 Climate. 19 Precipitation . 24 Environment . 24 Phenomena . 24 TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATION . -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRapHY ARCHIVaL MaTERIaL National Archives of Malawi (MNA), Zomba. National Archives at Kew (Co.525 Colonial Office Correspondence). Society of Malawi Library, Blantyre. Malawi Section, University Library, Chancellor College, Zomba. PUBLISHED BOOKS aND ARTICLES Abdallah, Y.B. 1973. The Yaos (Chikala Cha Wayao). Ed. M. Sanderson. (Orig 1919). London: Cass. Adams, J.S. and T. McShane. 1992. The Myth of Wild Africa. New York: Norton. Allan, W. 1965. African Husbandman. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd. Alpers, E.A. 1969. Trade, State and Society Among the Yao in the Nineteenth Century J. Afr. History 10: 405–420. ———. 1972. The Yao of Malawi in B. Pachai (ed) The Early History of Malawi pp 168–178. London: Longmans. ———. 1973. Towards a History of Expansion of Islam in East Africa in T.O. Ranger and N. Kimambo (eds) The Historical Study of African Religion pp 172–201. London: Heinemann. ———. 1975. Ivory and Slaves in East-Central Africa. London: Heinemann. Anderson-Morshead, A.M. 1897. The History of the Universities Mission to Central Africa 1859-96. London: UNICA. Anker, P. 2001. Imperial Ecology: Environmental Order in the British Empire. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. © The Author(s) 2016 317 B. Morris, An Environmental History of Southern Malawi, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-45258-6 318 BiblioGraphy Ansell, W.F.H. and R.J. Dowsett. 1988. Mammals of Malawi: An Annoted Checklist and Atlas. St Ives: Trendrine Press. Antill, R.M. 1945. A History of Native Grown Tobacco Industry in Nyasaland Nyasaland Agric. Quart. J. 8: 49–65. Baker, C.A. 1961. A Note on Nguru Immigration to Nyasaland Nyasaland J. -

Process for Preparing and Approving Resettlement Action Plan

Public Disclosure Authorized MINISTRY OF COMMERCE, TRADE AND INDUSTRY Public Disclosure Authorized RESETTLEMENT POLICY FRAMEWORK Great Lakes Trade Facilitation Project – SOP2 Project ID: No. P155329 Public Disclosure Authorized June 2018 Public Disclosure Authorized Table of Contents Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter One: Introduction and Project Description ............................................................................ 4 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Background ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Objectives of Resettlement Policy Framework .................................................................................. 5 1.4 Project Description ...................................................................................................................................... 5 1.4.1 Project Components ........................................................................................................................... 6 1.5 Institutional Arrangements .................................................................................................................... 10 1.5.1 Department of Foreign Trade ........................................................................................................ 11 1.5.2 Project Implementation