Continuum 119 a Belgian Art Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Auckland City Art Gallery

Frances Hodgkins 14 auckland city art gallery modern european paintings in new Zealand This exhibition brings some of the modern European paintings in New Zealand together for the first time. The exhibition is small largely because many galleries could not spare more paintings from their walls and also the conditions of certain bequests do not permit loans. Nevertheless, the standard is reasonably high. Chronologically the first modern movement represented is Impressionism and the latest is Abstract Expressionism, while the principal countries concerned are Britain and France. Two artists born in New Zealand are represented — Frances Hodgkins and Raymond Mclntyre — the former well known, the latter not so well as he should be — for both arrived in Europe before 1914 when the foundations of twentieth century painting were being laid and the earlier paintings here provide some indication of the milieu in which they moved. It is hoped that this exhibition may help to persuade the public that New Zealand is not devoid of paintings representing the serious art of this century produced in Europe. Finally we must express our sincere thanks to private owners and public galleries for their generous response to requests for loans. P.A.T. June - July nineteen sixty the catalogue NOTE: In this catalogue the dimensions of the paintings are given in inches, height before width JANKEL ADLER (1895-1949) 1 SEATED FIGURE Gouache 24} x 201 Signed ADLER '47 Bishop Suter Art Gallery, Nelson Purchased by the Trustees, 1956 KAREL APPEL (born 1921) Dutch 2 TWO HEADS (1958) Gouache 243 x 19i Signed K APPEL '58 Auckland City Art Gallery Presented by the Contemporary Art Society, 1959 JOHN BRATBY (born 1928) British 3 WINDOWS (1957) Oil on canvas 48x144 Signed BRATBY JULY 1957 Auckland City Art Gallery Presented by Auckland Gallery Associates, 1958 ANDRE DERAIN (1880-1954) French 4 LANDSCAPE Oil on canvas 21x41 J Signed A. -

Flemish Art 1880–1930

COMING FLEMISH ART 1880–1930 EDITOR KATHARINA VAN CAUTEREN HOME WITH ESSAYS BY ANNE ADRIAENS-PANNIER PATRICK BERNAUW PIET BOYENS KLAAS COULEMBIER JOHAN DE SMET MARK EYSKENS DAVID GARIFF LEEN HUET FERNAND HUTS PAUL HUVENNE PETER PAUWELS CONSTANTIJN PETRIDIS NIELS SCHALLEY HERWIG TODTS KATHARINA VAN CAUTEREN LUC VAN CAUTEREN SVEN VAN DORST CATHÉRINE VERLEYSEN Hubert Malfait Home from the Fields, 1923-1924 Oil on canvas, 120 × 100 cm COURTESY OF FRANCIS MAERE FINE ARTS CONTENTS 7 PREFACE 211 JAMES ENSOR’S KATHARINA VAN CAUTEREN WHIMSICAL QUEST FOR BLISS HERWIG TODTS 9 PREFACE FERNAND HUTS 229 WOUTERS WRITINGS 13 THE ROOTS OF FLANDERS HERWIG TODTS KATHARINA VAN CAUTEREN 253 EDGARD TYTGAT. 65 AUTHENTIC, SOUND AND BEAUTIFUL. ‘PEINTRE-IMAGIER’ THE RECEPTION OF LUC VAN CAUTEREN FLEMISH EXPRESSIONISM PAUL HUVENNE 279 CONSTANT PERMEKE. THE ETERNAL IN THE EVERYDAY 79 THE MOST FLEMISH FLEMINGS PAUL HUVENNE WRITE IN FRENCH PATRICK BERNAUW 301 GUST. DE SMET. PAINTER OF CONTENTMENT 99 A GLANCE AT FLEMISH MUSIC NIELS SCHALLEY BETWEEN 1890 AND 1930 KLAAS COULEMBIER 319 FRITS VAN DEN BERGHE. SURVEYOR OF THE DARK SOUL 117 FLEMISH BOHÈME PETER PAUWELS LEEN HUET 339 ‘PRIMITIVISM’ IN BELGIUM? 129 THE BELGIAN LUMINISTS IN AFRICAN ART AND THE CIRCLE OF EMILE CLAUS FLEMISH EXPRESSIONISM JOHAN DE SMET CONSTANTIJN PETRIDIS 149 BENEATH THE SURFACE. 353 LÉON SPILLIAERT. THE ART OF THE ART OF THE INDEFINABLE GUSTAVE VAN DE WOESTYNE ANNE ADRIAENS-PANNIER SVEN VAN DORST 377 THE EXPRESSIONIST IMPULSE 175 VALERIUS DE SAEDELEER. IN MODERN ART THE SOUL OF THE LANDSCAPE DAVID GARIFF PIET BOYENS 395 DOES PAINTING HAVE BORDERS? 195 THE SCULPTURE OF MARK EYSKENS GEORGE MINNE CATHÉRINE VERLEYSEN 6 PREFACE Dear Reader, 7 Just so you know, this book is not the Bible. -

Ensor to Permeke

06 • 10 • 2015 Ensor to Permeke A PASSION FOR BELGIAN ART BA cata Ensor 167x242 22/07/15 10:00 Page 1 ENTE VEILING mardi - dinsdag 06 • 10 • 2015 - 19.00 Ensor to Permeke A PASSION FOR BELGIAN ART 7 – 9, RUE ERNEST ALLARDSTRAAT (SABLON-ZAVEL) • B-1000 BRUXELLES - BRUSSEL T. +32 (0)2 511 53 24 • [email protected] WWW.BA-AUCTIONS.COM BA cata Ensor 167x242 22/07/15 10:00 Page 2 BA cata Ensor 167x242 22/07/15 10:00 Page 3 BA cata Ensor 167x242 22/07/15 10:00 Page 4 La collection Eric Drossart, le reflet d’une passion Lorsque je disputais la Coupe Davis dans les années soixante, et même au début de ma carrière chez Mc Cormack, je ne me connais- sais aucune affinité particulière avec l’Art. Tout a commencé lors de mon installation à Londres, au début des années quatre-vingt. J’y ai découvert le monde des galeries d’art, des ventes aux enchères et très vite cet univers fascinant s’est imposé à moi comme une évidence et devint une passion. Mon intérêt pour l’art belge, essentiellement celui de la fin du 19e siècle et du début du 20e siècle, répondait parfaitement à ma sensibilité naissante et à mon sentiment d’exilé. Dès 1991 j’ai donc commencé avec les encouragements de ma mère, qui adorait fouiner, à rechercher et à acquérir des œuvres d’artistes belges de cette période. Peu de temps après, j’ai eu la chance de rencontrer Sabine Taevernier qui est devenue, et qui est encore aujourd’hui, ma conseillère. -

Faculteit Letteren En Wijsbegeerte Vakgroep Kunst-, Muziek- En Theaterwetenschappen Academiejaar 2009-2010 Eerste Examenperiode

Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte Vakgroep Kunst-, Muziek- en Theaterwetenschappen Academiejaar 2009-2010 Eerste Examenperiode Artistieke afbeeldingen van het amusementsleven in het oeuvre van Gustave De Smet, Edgard Tytgat en Floris Jespers binnen het sociaal culturele spanningsveld van de jaren twintig Scriptie neergelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Master in de Kunstwetenschappen, Optie Beeldende Kunst door Willem Coppejans Promotor: Prof. Dr. Claire Van Damme INHOUDSTAFEL Voorwoord …………………………………………………………………………………………5 Status Quaestionis …………………………………………………………………………………6 1. Situering van de protagonisten in de jaren twintig en hun relatie ten opzichte van het amusementsleven ………………………………………………...…13 1.1 Gustave De Smet………………………………………………………………………………. 13 1.2 Edgard Tytgat………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 1.3 Floris Jespers…………………………………………………………………………………... 16 1.4 Besluit………………………………………………………………………………………….. 17 2 Sociaal historische invloed op het veelvuldige voorkomen van de thematiek van het amusementsleven in de Vlaamse kunst van de jaren twintig …………….. 18 2.1 Historische schets: het amusementsleven in de jaren twintig………………………………….. 18 2.1.1 De dolle jaren twintig?…………………………………………………………………………. 18 2.1.2 Bloei van de amusementscultuur ondanks een bar economisch klimaat………………………. 19 2.1.3 Het amusementsleven van de jaren twintig: voor elk wat wils………………………………... 20 2.1.3.1 Kermis…………………………………………………………………………………………. 20 2.1.3.2 Circus………………………………………………………………………………………….. 20 2.1.3.3 Kusttoerisme…………………………………………………………………………………… 21 2.1.3.4 -

G Er T Ja Nv an R Oo Ij

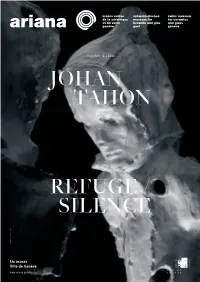

28.9.2019–5.4.2020 JOHAN TAHON REFUGE / SILENCE Photographie : Gert Jan van Rooij Press Kit 16 September 2019 Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 Press visits on request only Exhibition preview Friday 27 September 2019 at 6pm Musée Ariana Swiss Museum for Ceramics and Glass 10, avenue de la Paix 1202 Geneva - Switzerland Press kit available at “Presse”: www.ariana-geneve.ch Visuals, photos on request: [email protected] Un musée Ville de Genève www.ariana-geneve.ch Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 CONTENTS Johan Tahon. REFUGE/SILENCE p. 3 Biography of Johan Tahon p. 4 Events p. 8 Practical information p. 9 2 Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 J OHAN T AHON. REFUGE/SILENCE The Musée Ariana is proud to present Johan Tahon. REFUGE/SILENCE, in partnership with the Kunstforum gallery in Solothurn, from 28 September 2019 to 5 April 2020 in the space dedicated to contemporary creation. Johan Tahon, internationally renowned Belgian artist, is exhibiting a strong and committed body of work that reveals his deep connection with the ceramic medium. In the space devoted to contemporary creation, visitors enter a mystical world inhabited by hieratic monks, leading them into a second gallery where, in addition to the figures, pharmacy jars or albarelli are displayed. A direct reference to the history of faience, the ointments, powders and medicines contained in such vessels were intended to heal both body and soul. A sensitive oeuvre reflecting the human condition Johan Tahon’s oeuvre evolves in an original and individual way. -

The Belgian Contribution to Global 1968 Gerd Rainer Horn

The Belgian Contribution to Global 1968 Gerd Rainer Horn To cite this version: Gerd Rainer Horn. The Belgian Contribution to Global 1968. Views From Abroad : Foreign Historians on Belgium, special English-language issue of Revue Belge d’Histoire Contemporaine, 2005, pp.597- 635. hal-01020652 HAL Id: hal-01020652 https://hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01020652 Submitted on 8 Jul 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Belgian Contribution to Global 1968 GERD-RAINER HORN ____Senior Lecturer in 20th Century History, Department of History – University of Warwick The calendar year of 1968 is almost universally associated with student un- rest. Belgium fits into this picture rather well, with major student mobilisa- tions in Leuven and Brussels occurring in the first half of that notoriously restless calendar year.1 Yet all-inclusive assessments of the social movements and political reconfigurations happening that year, not only in Belgium but elsewhere in Europe and North America as well, must go beyond the rela- tively narrow confines of university student milieus. For the purposes of this essay, I propose also to address fresh developments occurring within the worlds of labor and cultural productions. -

Untitled for the Exhibition Body Talk Presented at WIELS, Brussels 2015

1 Inhoudstafel Inhoudstafel ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Feast of Fools. Bruegel herontdekt ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Meer dan alleen een tentoonstelling .................................................................................................................................... 6 Titel ........................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Kunstwerken ‘Feast of Fools. Bruegel herontdekt’............................................................................................................ 8 Bruiklenen ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 8 1. Introductie ............................................................................................................................................................................ 8 2. Back to the Roots ............................................................................................................................................................ 8 3. Everybody Hurts ............................................................................................................................................................. -

Middle Gate II – the Story of Dymphna EN 15.09–04.11.2018

Middle Gate II – The Story of Dymphna EN 15.09–04.11.2018 1 Middle Gate II – The Story of Dymphna 15.09–04.11.2018 2 Glossary 7 Introduction 10 Little Dove (To Dymphna) Lenny Peeters 14 Pilgrimage Vincent Van Menen 20 Artists 22 The Crown & Migration 58 The Sword & Sexual Violence 118 The Devil & Madness 168 The Book & Spirituality 212 Colofon Dr. Frits Sano, photograph on glass, photograph supposedly taken by dr. Paul Sano (collection Guy Rombouts) 4 5 Introduction Middle Gate II 15.09–04.11.2018 With the exhibition Middle Gate (2013), Painting by Luc Tuymans and Narcisse Jan Hoet returned to his origins, Tordoir, and the first chapter of Anselm announcing he wanted to depart from Franke’s Animism project. Yet central the middle gate. As did the exhibition, to all this is the figure of Jan Hoet, who that activated art’s potentiality and with Chambres d’Amis changed the idea offered immediate added value to both of what an exhibition can be. Earlier, he people and society. had already curated ground-breaking overviews like Aktuele kunst in België: Middle Gate testified of a love of art – inzicht/overzicht, overzicht/inzicht by effectively departing from works of art [Contemporary Art in Belgium: Insight/ that had been chosen for their intensity Overview, Overview/Insight] or Art in – and a high degree of casualness. This Europe after 1968. After Chambres also translated itself organisationally, d ‘Amis he would also take on with a problem solving attitude as Documenta IX. permanent alternative to a monetised operation that is based on professional, Let us continue to include Middle market and marketing mechanisms. -

Press Release Brafa 2020 All Together Different

PRESS RELEASE BRAFA 2020 ALL TOGETHER DIFFERENT Over more than fifty years, Galerie Oscar De Vos built a tradition of prestigious exhibitions on Modern Belgian Art, with an emphasis on the art of The Latem School. Artists such as George Minne, Valerius De Saedeleer, Gustave Van de Woestyne, Emile Claus, Albert Servaes, Constant Permeke, Gust. De Smet, Frits Van den Berghe and Hubert Malfait enjoy the appreciation of a large audience throughout museum exhibitions, publications in Belgium and abroad. Each of these artists loved the nature of Latem. There they created their works spontaneously and interacted with the other artists who resided in the village. The region of Flanders has long been an area rich in art. On the outskirts of the city Ghent, along the river Lys, artists relocated to the village of Sint-Martens-Latem. In Flanders, artists converged on Latem because of its beauty. In this pastoral environment were born a great many attractive works that could not have been originated in any city. The artworks on show during BRAFA 2020 will mainly be divided in two thematic sections: Symbolism and Expressionism (1890-1930). The collection of Galerie Oscar De Vos for the 65th BRAFA edition will mark this period as part of the flow of art history. The focus will be on artworks of an important provenance, being fresh on the art market and that have been exhibited in international art institutions, such as Venice Art Biennale, Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum, Eindhoven Van Abbe Museum, Hamburg Kunsthaus, London Royal Academy of Arts, Maastricht Bonnefanten Museum, Sao Paolo Museo de Arta Moderna. -

Moderne Kunst

Moderne kunst Kunstwerken van ARMAN, ALECHINSKY, BROOD, DELVAUX, RAVEEL, VENET, TUYMANS en nog vele anderen. Startdatum Thursday 05 December 2019 10:00 Bezichtiging Wednesday December 11 2019 from 15:00 until 17:00 BE-2630 Aartselaar, Helststraat 47. Einddatum Zondag 15 december 2019 vanaf 20:00 Afgifte Friday December 20 2019 from 10:00 until 12:00 BE-2630 Aartselaar, Helststraat 47 Online bidding only! Voor meer informatie en voorwaarden: www.moyersoen.be 15/12/2019 05:00 Kavel Omschrijving Openingsbod 1 Henri MICHAULT - Composition 540€ Beautiful black and white lithography, drawn and numbered in pencil. Framed in a white baking frame to show the work perfectly. Dimensions: 75x96 cm 2 Fernandez ARMAN 2400€ Exceptionally stylish bronze sculpture on foot with gilt patina. Signed and numbered on 99 copies. height: 30 cm 3 DON KEN - Mickey 600€ Original gouache and drawing on handmade thick paper - drawn. Dimensions: 94x75 cm 4 DON KEN - Donald 600€ Original gouache and drawing on handmade thick paper - drawn. Dimensions: 94x75 cm 5 SALVADOR DALI - L'éléphant spatial 300€ Graphic work heightened with gold paint - drawn and numbered EA (Artists proof). Professionally framed with multiple passe-partouts. Dimensions 91 x 107 cm 6 Bram BOGART 1440€ Rare Aquagravure / relief print with a typical representation. Signed, dated '87 and numbered on 99 copies. Dimensions: 101x101 cm 7 Pierre ALECHINSKY - Composition with cobra 540€ Color lithography drawn and numbered in pencil. Professionally framed with multiple passe-partouts. Dimensions: 98x80 cm Kavel Omschrijving Openingsbod 8 Pierre ALECHINSKY and Christian DOTREMONT - J'écris à Gloria 900€ Color lithography - collaboration of the 2 artists - drawn and numbered in pencil by Alechinsky. -

Press Release Brafa 2018

PRESS RELEASE BRAFA 2018 Galerie Oscar De Vos is pleased to announce the selected artworks for BRAFA 2018 at Tour & Taxis, Brussels. The exhibition focuses on quality works of MODERN BELGIAN ART FROM ABOUT 1890-1930. More than 40 oil paintings and a fine selection of works on paper and sculptures (marble , bronze, plaster) will expose the wide-ranging art of the Latem School is the collection will show how radically the art movements in Belgian, and even internationally, have been changed in such a short time period. Most of the artworks belonged to private collections and these artworks will be – even for the first time – on show during BRAFA 2018 since decades. Special attention is given to: Kneeling youth (1896) with gold leaf patina by George Minne Nasturtiums (1901) by Emile Claus Rest after the haymaking (1902) by Emile Claus Spring morning in Wales (1920) by Valerius De Saedeleer Wrapped up peasant (1910) by Gustave Van de Woestyne Playing boy in the snow (1918) by Frits Van den Berghe The lumberman (1930) by Gust. De Smet and the magnum opus of Frits Van den Berghe: The companions (1932). These paintings have been exhibited in major international museums, among others in Antwerp, Brussels, Ghent, Leningrad, Moscow, Oslo, Stockholm and Tokyo. Museum catalogues, scientific publications and articles illustrate and confirm the importance of these artworks in specific and the Latem School artists in general. These Belgian avant-garde artists were protagonists of international art movements such as Impressionism, Symbolism, Expressionism and Surrealism. Over the last fifty years, Galerie Oscar De Vos has established its name in this specialized domain, contributing to international museum exhibitions and publications, and participating in international art fairs. -

Moderne Kunst

MODERNE KUNST Div. schilderijen, etsen, lithografieën en sculpturen Startdatum Tuesday 05 December 2017 10:00 Bezichtiging Wednesday 06 December 2017 from 14:00 to 16:00 Wednesday 13 December 2017 from 14:00 to 16:00 BE-2630 Aartselaar, Helststraat 47 Einddatum Vrijdag 15 december 2017 vanaf 19:00 Afgifte Friday 22 December 2017 from 10:00 to 12:00 BE-2630 Aartselaar, Helststraat 47 Online bidding only! Voor meer informatie en voorwaarden: www.moyersoen.be 19/12/2017 12:42 Kavel Omschrijving Openingsbod 1 Guillaume Corneille - Femme et oiseau 600€ Dimensions frame: 135 x 109 cm Color lithograph signed, dated and numbered EA 2009 13 copies. Delivery subject to the special arrangements for taxing the margin. VAT is not deductible, excl. VAT and auction fees on auction fees. 2 Panamarenko - Scotch Gambit 240€ Dimensions frame: 137 x 105 cm Offset - This work framed in a white frame to get better justice to the work. Delivery subject to the special arrangements for taxing the margin. VAT is not deductible, excl. VAT and auction fees on auction fees. 3 Christo Java Chef - The Gates 420€ Dimensions frame: 121 x 91 cm The Gates, Project for Central Park - New York Offset Lithography signed in blue pencil. This work framed in a white barge to get better result. 4 Java Chef Christo - Over the river - the Arkansas river 360€ Dimensions frame: 107 x 85 cm Offset lithograph signed in pencil and numbered 300/500 Framed in white. 5 Karel Appel - Composition 720€ Dimensional Framework: 91 x 110 cm Exceptional screen printing which represents the power of his work .