Brussels, the Avant-Garde, and Internationalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life and Letters of William Sharp and “Fiona Macleod”

The Life and Letters of William Sharp and “Fiona Macleod” Volume 2: 1895-1899 W The Life and Letters of ILLIAM WILLIAM F. HALLORAN William Sharp and What an achievement! It is a major work. The lett ers taken together with the excellent H F. introductory secti ons - so balanced and judicious and informati ve - what emerges is an amazing picture of William Sharp the man and the writer which explores just how “Fiona Macleod” fascinati ng a fi gure he is. Clearly a major reassessment is due and this book could make it ALLORAN happen. Volume 2: 1895-1899 —Andrew Hook, Emeritus Bradley Professor of English and American Literature, Glasgow University William Sharp (1855-1905) conducted one of the most audacious literary decep� ons of his or any � me. Sharp was a Sco� sh poet, novelist, biographer and editor who in 1893 began The Life and Letters of William Sharp to write cri� cally and commercially successful books under the name Fiona Macleod. This was far more than just a pseudonym: he corresponded as Macleod, enlis� ng his sister to provide the handwri� ng and address, and for more than a decade “Fiona Macleod” duped not only the general public but such literary luminaries as William Butler Yeats and, in America, E. C. Stedman. and “Fiona Macleod” Sharp wrote “I feel another self within me now more than ever; it is as if I were possessed by a spirit who must speak out”. This three-volume collec� on brings together Sharp’s own correspondence – a fascina� ng trove in its own right, by a Victorian man of le� ers who was on in� mate terms with writers including Dante Gabriel Rosse� , Walter Pater, and George Meredith – and the Fiona Macleod le� ers, which bring to life Sharp’s intriguing “second self”. -

Auckland City Art Gallery

Frances Hodgkins 14 auckland city art gallery modern european paintings in new Zealand This exhibition brings some of the modern European paintings in New Zealand together for the first time. The exhibition is small largely because many galleries could not spare more paintings from their walls and also the conditions of certain bequests do not permit loans. Nevertheless, the standard is reasonably high. Chronologically the first modern movement represented is Impressionism and the latest is Abstract Expressionism, while the principal countries concerned are Britain and France. Two artists born in New Zealand are represented — Frances Hodgkins and Raymond Mclntyre — the former well known, the latter not so well as he should be — for both arrived in Europe before 1914 when the foundations of twentieth century painting were being laid and the earlier paintings here provide some indication of the milieu in which they moved. It is hoped that this exhibition may help to persuade the public that New Zealand is not devoid of paintings representing the serious art of this century produced in Europe. Finally we must express our sincere thanks to private owners and public galleries for their generous response to requests for loans. P.A.T. June - July nineteen sixty the catalogue NOTE: In this catalogue the dimensions of the paintings are given in inches, height before width JANKEL ADLER (1895-1949) 1 SEATED FIGURE Gouache 24} x 201 Signed ADLER '47 Bishop Suter Art Gallery, Nelson Purchased by the Trustees, 1956 KAREL APPEL (born 1921) Dutch 2 TWO HEADS (1958) Gouache 243 x 19i Signed K APPEL '58 Auckland City Art Gallery Presented by the Contemporary Art Society, 1959 JOHN BRATBY (born 1928) British 3 WINDOWS (1957) Oil on canvas 48x144 Signed BRATBY JULY 1957 Auckland City Art Gallery Presented by Auckland Gallery Associates, 1958 ANDRE DERAIN (1880-1954) French 4 LANDSCAPE Oil on canvas 21x41 J Signed A. -

Flemish Art 1880–1930

COMING FLEMISH ART 1880–1930 EDITOR KATHARINA VAN CAUTEREN HOME WITH ESSAYS BY ANNE ADRIAENS-PANNIER PATRICK BERNAUW PIET BOYENS KLAAS COULEMBIER JOHAN DE SMET MARK EYSKENS DAVID GARIFF LEEN HUET FERNAND HUTS PAUL HUVENNE PETER PAUWELS CONSTANTIJN PETRIDIS NIELS SCHALLEY HERWIG TODTS KATHARINA VAN CAUTEREN LUC VAN CAUTEREN SVEN VAN DORST CATHÉRINE VERLEYSEN Hubert Malfait Home from the Fields, 1923-1924 Oil on canvas, 120 × 100 cm COURTESY OF FRANCIS MAERE FINE ARTS CONTENTS 7 PREFACE 211 JAMES ENSOR’S KATHARINA VAN CAUTEREN WHIMSICAL QUEST FOR BLISS HERWIG TODTS 9 PREFACE FERNAND HUTS 229 WOUTERS WRITINGS 13 THE ROOTS OF FLANDERS HERWIG TODTS KATHARINA VAN CAUTEREN 253 EDGARD TYTGAT. 65 AUTHENTIC, SOUND AND BEAUTIFUL. ‘PEINTRE-IMAGIER’ THE RECEPTION OF LUC VAN CAUTEREN FLEMISH EXPRESSIONISM PAUL HUVENNE 279 CONSTANT PERMEKE. THE ETERNAL IN THE EVERYDAY 79 THE MOST FLEMISH FLEMINGS PAUL HUVENNE WRITE IN FRENCH PATRICK BERNAUW 301 GUST. DE SMET. PAINTER OF CONTENTMENT 99 A GLANCE AT FLEMISH MUSIC NIELS SCHALLEY BETWEEN 1890 AND 1930 KLAAS COULEMBIER 319 FRITS VAN DEN BERGHE. SURVEYOR OF THE DARK SOUL 117 FLEMISH BOHÈME PETER PAUWELS LEEN HUET 339 ‘PRIMITIVISM’ IN BELGIUM? 129 THE BELGIAN LUMINISTS IN AFRICAN ART AND THE CIRCLE OF EMILE CLAUS FLEMISH EXPRESSIONISM JOHAN DE SMET CONSTANTIJN PETRIDIS 149 BENEATH THE SURFACE. 353 LÉON SPILLIAERT. THE ART OF THE ART OF THE INDEFINABLE GUSTAVE VAN DE WOESTYNE ANNE ADRIAENS-PANNIER SVEN VAN DORST 377 THE EXPRESSIONIST IMPULSE 175 VALERIUS DE SAEDELEER. IN MODERN ART THE SOUL OF THE LANDSCAPE DAVID GARIFF PIET BOYENS 395 DOES PAINTING HAVE BORDERS? 195 THE SCULPTURE OF MARK EYSKENS GEORGE MINNE CATHÉRINE VERLEYSEN 6 PREFACE Dear Reader, 7 Just so you know, this book is not the Bible. -

Ensor to Permeke

06 • 10 • 2015 Ensor to Permeke A PASSION FOR BELGIAN ART BA cata Ensor 167x242 22/07/15 10:00 Page 1 ENTE VEILING mardi - dinsdag 06 • 10 • 2015 - 19.00 Ensor to Permeke A PASSION FOR BELGIAN ART 7 – 9, RUE ERNEST ALLARDSTRAAT (SABLON-ZAVEL) • B-1000 BRUXELLES - BRUSSEL T. +32 (0)2 511 53 24 • [email protected] WWW.BA-AUCTIONS.COM BA cata Ensor 167x242 22/07/15 10:00 Page 2 BA cata Ensor 167x242 22/07/15 10:00 Page 3 BA cata Ensor 167x242 22/07/15 10:00 Page 4 La collection Eric Drossart, le reflet d’une passion Lorsque je disputais la Coupe Davis dans les années soixante, et même au début de ma carrière chez Mc Cormack, je ne me connais- sais aucune affinité particulière avec l’Art. Tout a commencé lors de mon installation à Londres, au début des années quatre-vingt. J’y ai découvert le monde des galeries d’art, des ventes aux enchères et très vite cet univers fascinant s’est imposé à moi comme une évidence et devint une passion. Mon intérêt pour l’art belge, essentiellement celui de la fin du 19e siècle et du début du 20e siècle, répondait parfaitement à ma sensibilité naissante et à mon sentiment d’exilé. Dès 1991 j’ai donc commencé avec les encouragements de ma mère, qui adorait fouiner, à rechercher et à acquérir des œuvres d’artistes belges de cette période. Peu de temps après, j’ai eu la chance de rencontrer Sabine Taevernier qui est devenue, et qui est encore aujourd’hui, ma conseillère. -

Levy, Carl. 2017. Malatesta and the War Interventionist Debate 1914-1917: from the ’Red Week’ to the Russian Revolutions

Levy, Carl. 2017. Malatesta and the War Interventionist Debate 1914-1917: from the ’Red Week’ to the Russian Revolutions. In: Matthew S. Adams and Ruth Kinna, eds. Anarchism, 1914-1918: Internationalism, Anti-Militarism and War. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 69-92. ISBN 9781784993412 [Book Section] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/20790/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] 85 3 Malatesta and the war interventionist debate 1914–17: from the ‘Red Week’ to the Russian revolutions Carl Levy This chapter will examine Errico Malatesta’s (1853–1932) position on intervention in the First World War. The background to the debate is the anti-militarist and anti-dynastic uprising which occurred in Italy in June 1914 (La Settimana Rossa) in which Malatesta was a key actor. But with the events of July and August 1914, the alliance of socialists, republicans, syndicalists and anarchists was rent asunder in Italy as elements of this coalition supported intervention on the side of the Entente and the disavowal of Italy’s treaty obligations under the Triple Alliance. Malatesta’s dispute with Kropotkin provides a focus for the anti-interventionist campaigns he fought internationally, in London and in Italy.1 This chapter will conclude by examining Malatesta’s discussions of the unintended outcomes of world war and the challenges and opportunities that the fracturing of the antebellum world posed for the international anarchist movement. -

"Nominees 2019"

• EUROPEAN UNION PRIZE FOR EUm1esaward CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE 19 MIES VAN DER ROHE Name Work country Work city Offices Pustec Square Albania Pustec Metro_POLIS, G&K Skanderbeg Square Albania Tirana 51N4E, Plant en Houtgoed, Anri Sala, iRI “New Baazar in Tirana“ Restoration and Revitalization Albania Tirana Atelier 4 arTurbina Albania Tirana Atelier 4 “Lalez, individual Villa” Albania Durres AGMA studio Himara Waterfront Albania Himarë Bureau Bas Smets, SON-group “The House of Leaves". National Museum of Secret Surveillance Albania Tirana Studio Terragni Architetti, Elisabetta Terragni, xycomm, Daniele Ledda “Aticco” palace Albania Tirana Studio Raça Arkitektura “Between Olive Trees” Villa Albania Tirana AVatelier Vlora Waterfront Promenade Albania Vlorë Xaveer De Geyter Architects The Courtyard House Albania Shkodra Filippo Taidelli Architetto "Tirana Olympic Park" Albania Tirana DEAstudio BTV Headquarter Vorarlberg and Office Building Austria Dornbirn Rainer Köberl, Atelier Arch. DI Rainer Köberl Austrian Embassy Bangkok Austria Vienna HOLODECK architects MED Campus Graz Austria Graz Riegler Riewe Architekten ZT-Ges.m.b.H. Higher Vocational Schools for Tourism and Catering - Am Wilden Kaiser Austria St. Johann in Tirol wiesflecker architekten zt gmbh Farm Building Josef Weiss Austria Dornbirn Julia Kick Architektin House of Music Innsbruck Austria Innsbruck Erich Strolz, Dietrich | Untertrifaller Architekten Exhibition Hall 09 - 12 Austria Dornbirn Marte.Marte Architekten P2 | Urban Hybrid | City Library Innsbruck Austria Innsbruck -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

Continuum 119 a Belgian Art Perspective

CONTINUUM 119 A BELGIAN ART PERSPECTIVE OFF-PROGRAM GROUP SHOW 15/04/19 TO 31/07/19 Art does not belong to anyone, it usually passes on from one artist to the next, from one viewer to the next. We inherit it from the past when it served as a cultural testimony to who we were, and we share it with future generations, so they may understand who we are, what we fear, what we love and what we value. Over centuries, civilizations, societies and individuals have built identities around art and culture. This has perhaps never been more so than today. As an off-program exhibition, I decided to invite five Belgian artists whose work I particularly like, to answer back with one of their own contemporary works to a selection of older works that helped build my own Belgian artistic identity. In no way do I wish to suggest that their current work is directly inspired by those artists they will be confronted with. No, their language is mature and singular. But however unique it may be, it can also be looked at in the context of the subtle evolution from their history of art, as mutations into new forms that better capture who these artists are, and the world they live in. Their work can be experienced within an artistic continuum, in which pictorial elements are part of an inheritance, all the while remaining originally distinct. On each of these Belgian artists, I imposed a work from the past, to which they each answered back with a recent work of their own. -

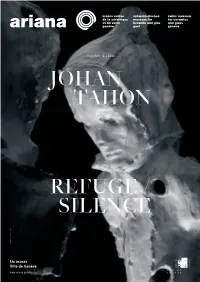

G Er T Ja Nv an R Oo Ij

28.9.2019–5.4.2020 JOHAN TAHON REFUGE / SILENCE Photographie : Gert Jan van Rooij Press Kit 16 September 2019 Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 Press visits on request only Exhibition preview Friday 27 September 2019 at 6pm Musée Ariana Swiss Museum for Ceramics and Glass 10, avenue de la Paix 1202 Geneva - Switzerland Press kit available at “Presse”: www.ariana-geneve.ch Visuals, photos on request: [email protected] Un musée Ville de Genève www.ariana-geneve.ch Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 CONTENTS Johan Tahon. REFUGE/SILENCE p. 3 Biography of Johan Tahon p. 4 Events p. 8 Practical information p. 9 2 Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 J OHAN T AHON. REFUGE/SILENCE The Musée Ariana is proud to present Johan Tahon. REFUGE/SILENCE, in partnership with the Kunstforum gallery in Solothurn, from 28 September 2019 to 5 April 2020 in the space dedicated to contemporary creation. Johan Tahon, internationally renowned Belgian artist, is exhibiting a strong and committed body of work that reveals his deep connection with the ceramic medium. In the space devoted to contemporary creation, visitors enter a mystical world inhabited by hieratic monks, leading them into a second gallery where, in addition to the figures, pharmacy jars or albarelli are displayed. A direct reference to the history of faience, the ointments, powders and medicines contained in such vessels were intended to heal both body and soul. A sensitive oeuvre reflecting the human condition Johan Tahon’s oeuvre evolves in an original and individual way. -

Verzameld Werk. Deel 2

Verzameld werk. Deel 2 August Vermeylen onder redactie van Herman Teirlinck en anderen bron August Vermeylen, Verzameld werk. Deel 2 (red. Herman Teirlinck en anderen). Uitgeversmaatschappij A. Manteau, Brussel 1951 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/verm036verz02_01/colofon.htm © 2007 dbnl / erven August Vermeylen 5 Verzamelde opstellen Eerste bundel August Vermeylen, Verzameld werk. Deel 2 7 AAN PROSPER VAN LANGENDONCK EN ALFRED HEGENSCHEIDT August Vermeylen, Verzameld werk. Deel 2 9 Voorrede Toen in 1904 de eerste uitgave van deze ‘Verzamelde Opstellen’ verscheen, werden zij door de volgende woorden ingeleid: ‘Deze stukken blijven hier naar tijdsorde geschikt, want ze zijn het beeld van een jeugd in gestadige wording. Ook heb ik geen enkel idee gewijzigd, al spreekt het vanzelf, dat menige opvatting van negen of tien jaar geleden met mijn tegenwoordige zienswijze niet meer strookt. Maar de vroegere opstellen leren later geschrijf beter begrijpen, en dan - ik hecht meer aan den toon, dan aan de onfeilbaarheid der gedachte. Als men voor 't eerst in 't werkdadige leven treedt, heeft men veel vragen uit te vechten met zich zelf en met de mensen: het is dan zo natuurlijk, dat men de absolute leuzen, waar men gaarne zijn eigen zedelijk leven op grondvesten zou, en die daar volkomen op haar plaats zijn, ook tegenover de pas-ontdekte maatschappelijke wereld gaat stellen. En 't was even schoon, sommige woorden toen te spreken, als het me gepast zou voorkomen, ze thans te laten rusten: Cosi n' andammo infino alla lumiera, Parlando cose che il tacere è bello, Si com'era il parlar colà dov'era.’ August Vermeylen, Verzameld werk. -

Literature of the Low Countries

Literature of the Low Countries A Short History of Dutch Literature in the Netherlands and Belgium Reinder P. Meijer bron Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries. A short history of Dutch literature in the Netherlands and Belgium. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague / Boston 1978 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/meij019lite01_01/colofon.htm © 2006 dbnl / erven Reinder P. Meijer ii For Edith Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries vii Preface In any definition of terms, Dutch literature must be taken to mean all literature written in Dutch, thus excluding literature in Frisian, even though Friesland is part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in the same way as literature in Welsh would be excluded from a history of English literature. Similarly, literature in Afrikaans (South African Dutch) falls outside the scope of this book, as Afrikaans from the moment of its birth out of seventeenth-century Dutch grew up independently and must be regarded as a language in its own right. Dutch literature, then, is the literature written in Dutch as spoken in the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the so-called Flemish part of the Kingdom of Belgium, that is the area north of the linguistic frontier which runs east-west through Belgium passing slightly south of Brussels. For the modern period this definition is clear anough, but for former times it needs some explanation. What do we mean, for example, when we use the term ‘Dutch’ for the medieval period? In the Middle Ages there was no standard Dutch language, and when the term ‘Dutch’ is used in a medieval context it is a kind of collective word indicating a number of different but closely related Frankish dialects. -

August Vermeylenkring

De August Vermeylenkring Roel De Groof De August Vermeylenkring Politiek-culturele actie van progressieve en socialistische intellectuelen in Brussel (1954-2004) Uitgegeven met de steun van: het Ministerie van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap, Administratie Cultuur de Vlaamse gemeenschapscommissie de minister-president van de Vlaamse regering Erecomité August Vermeylenkring 50 ! Vic Anciaux • Frank Beke • Ingrid Bens • Jos Bertrand • Rik Boel • Annie Bonnijns • Philippe Bossaert • Henk Brat • Wilfried Decrock • Eric De Loof • Lisette Denberg • Simone Deridder • Pieter Frantzen • Robert Geerts • Karel Hagenaar • Dirk Leonard • Silvain Loccufier • Madeline Lutjeharms • Camiel Maerivoet • Daniela Martin • Frans Ramael • Frans Schellens • Hugo Schurmans • Pascal Smet • Dany Van Brempt • Frank Vandenbroucke • Anne-Marie Vandergeeten • Anne Van Lancker • Louis Vermoote • Joz Wyninckx Omslagontwerp: Danni Elskens Boekverzorging: Boudewijn Bardyn Druk: Schaubroeck, Nazareth © 2004 vubpress Waversesteenweg , Brussel Fax: ++ [email protected] www.vubpress.be D / / / Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. Inhoud Inleiding 9 Hoofdstuk 1 –De culturele legitimatie van de 19 Vlaamse beweging na 1945 1. Het odium van de culturele collaboratie 19 2. De oprichting van cultuurhistoriografische en 21 literaire ‘monumenten’ 3. Literaire groei, modernisering en experimentalisme: 23 naar een cultuur van het Vrije Woord 4. De oprichting van het August Vermeylenfonds 25 Hoofdstuk 11 –De August Vermeylenkring Brussel: 29 doel, bestuur en netwerk 1. Doel en oprichting van de August Vermeylenkring 29 2. Hendrik Fayat: ‘flamingant, want socialist’ 31 3. Lydia De Pauw-Deveen: vier generaties vrijzinnig 37 flamingantisme en Rode Leeuwin 4. Besturen in vriendschap en met de kracht van een overtuiging 39 5.