Flemish Art 1880–1930

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Challenges for Flemish Agriculture and Horticulture

LARA '18 LARA '18 CHALLENGES FOR FLEMISH AGRICULTURE AND HORTICULTURE DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE & FISHERIES CHALLENGES FOR FLEMISH AGRICULTURE AND HORTICULTURE The seventh edition of the Flemish Agriculture Report (LARA) was published in 2018. The report deals with the challenges for Flemish agriculture and horticulture. At the same time, it pro- vides a detailed description of the subsectors. A SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) also takes place per subsector. Between the chapters, experts from policy, research and civil society give their vision on challenges faced by Flemish agriculture and how the sector should deal with them. This is a translation of the summary of the report. You’ll find the entire report in Dutch on www.vlaanderen.be/landbouwrapport. © Flemish Government, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries Platteau J., Lambrechts G., Roels K., Van Bogaert T., Luypaert G. & Merckaert B. (eds.) (2019) Challenges for Flemish agriculture and horticulture, Agriculture Report 2018, Summary, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brussels. D/2019/3241/075 1 CURRENT SITUATION AGRICULTURE IS CHARACTERISED BY ECONOMIES OF SCALE, SPECIALISATION, DIVERSIFICATI- ON AND INNOVATION In 2017, Flanders had 23,225 agricultural businesses, 78% of which were of a professional nature. Compa- red to 2007, the number of agricultural holdings has decreased by slightly more than a quarter, a decrease of 3% per year on average. In particular smaller farms stop their activities, which leads to a constant increase in scale. In 2017, agriculture and horticulture as a whole covered an area of 610,971 hectares. Thereof, the largest part is accounted for by fodder crops (maize and meadows) and cereals, with 56% and 21% respectively. -

Landslides in Belgium—Two Case Studies in the Flemish Ardennes and the Pays De 20 Herve

Landslides in Belgium—Two Case Studies in the Flemish Ardennes and the Pays de 20 Herve Olivier Dewitte, Miet Van Den Eeckhaut, Jean Poesen and Alain Demoulin Abstract Most landslides in Belgium, and especially the largest features, do not occur in the Ardenne, where the relief energy and the climate conditions seem most favourable. They appear in regions located mainly north of them where the lithology consists primarily of unconsolidated material. They develop on slopes that are relatively smooth, and their magnitude is pretty large with regard to that context. An inventory of more than 300 pre-Holocene to recent landslides has been mapped. Twenty-seven percent of all inventoried landslides are shallow complex landslides that show signs of recent activity. The remaining landslides are deep-seated features and rotational earth slides dominate (n > 200). For such landslides, the average area is 3.9 ha, but affected areas vary from 0.2 to 40.4 ha. The exact age of the deep-seated landslides is unknown, but it is certain that during the last century no such landslides were initiated. Both climatic and seismic conditions during the Quaternary may have triggered landslides. The produced landslide inventory is a historical inventory containing landslides of different ages and triggering events. Currently, only new shallow landslides or reactivations within existing deep-seated landslides occur. The focus on the Hekkebrugstraat landslide in the Flemish Ardennes allows us to understand the recent dynamics of a large reactivated landslide. It shows the complexity of the interactions between natural and human-induced processes. The focus on the Pays the Herve allows for a deeper understanding of landslide mechanisms and the cause of their origin in natural environmental conditions. -

Auckland City Art Gallery

Frances Hodgkins 14 auckland city art gallery modern european paintings in new Zealand This exhibition brings some of the modern European paintings in New Zealand together for the first time. The exhibition is small largely because many galleries could not spare more paintings from their walls and also the conditions of certain bequests do not permit loans. Nevertheless, the standard is reasonably high. Chronologically the first modern movement represented is Impressionism and the latest is Abstract Expressionism, while the principal countries concerned are Britain and France. Two artists born in New Zealand are represented — Frances Hodgkins and Raymond Mclntyre — the former well known, the latter not so well as he should be — for both arrived in Europe before 1914 when the foundations of twentieth century painting were being laid and the earlier paintings here provide some indication of the milieu in which they moved. It is hoped that this exhibition may help to persuade the public that New Zealand is not devoid of paintings representing the serious art of this century produced in Europe. Finally we must express our sincere thanks to private owners and public galleries for their generous response to requests for loans. P.A.T. June - July nineteen sixty the catalogue NOTE: In this catalogue the dimensions of the paintings are given in inches, height before width JANKEL ADLER (1895-1949) 1 SEATED FIGURE Gouache 24} x 201 Signed ADLER '47 Bishop Suter Art Gallery, Nelson Purchased by the Trustees, 1956 KAREL APPEL (born 1921) Dutch 2 TWO HEADS (1958) Gouache 243 x 19i Signed K APPEL '58 Auckland City Art Gallery Presented by the Contemporary Art Society, 1959 JOHN BRATBY (born 1928) British 3 WINDOWS (1957) Oil on canvas 48x144 Signed BRATBY JULY 1957 Auckland City Art Gallery Presented by Auckland Gallery Associates, 1958 ANDRE DERAIN (1880-1954) French 4 LANDSCAPE Oil on canvas 21x41 J Signed A. -

Persoverzicht

BIJLAGE BIJ HET FARO-JAARVERSLAG VAN 2012 FARO IN DE MEDIA . JANUARI . Eliane Van den Ende, Het Erfgoedfonds van de Koning-Boudewijnstichting viert zijn 25- jarig bestaan, Focus, januari 2012, p. 1-4 (vermelding Marc Jacobs / FARO) . (RLA), Heilige Gudula al 1300 jaar vereerd, Het Laatste Nieuws Denderstreek, 5 januari 2012, p.19. (vermelding Erfgoeddag) . 2012, het jaar der verjaardagen, Gazet Van Antwerpen, 7 januari 2012, p.6. (vermelding Erfgoeddag) . (SVER), Nieuws uit uw gemeente – Retie HELDEN, Gazet Van Antwerpen Kempen, 10 januari 2012, p. 40. (vermelding Erfgoeddag) . Jan-Pieter De Vlieger, Het café, waar België kampioenen kweekt. Typisch Belgische cafécultuur ideale voedingsbodem voor succes in sporten als biljart, darts en tafelvoetbal. De Morgen, 10 januari 2012, p. 7. (vermelding Rob Belemans / FARO) . (LVDB), Jan De Lichte, Nieuws uit uw gemeente – Aalst, Gazet Van AntwerpenWaasland, 11 januari 2012, p. 40. (vermelding Erfgoeddag) . (EMV), Huysmanhoeve klinkt met buren op nieuwe jaar en maakt expo Wielsport bekend, Het Nieuwsblad Meetjesland-Leiestreek, 12 januari 2012, p. 26. (PVDB), Figuranten gezocht voor spektakel over Jan De Lichte, Het Nieuwwsblad Dender, 14 januari 2012, p. 40. (vermelding Erfgoeddag) . (JSA), Huysmanhoeve mikt op jongeren en kinderen, Het Laatse Nieuws Gent-Eeklo- Deinze, 23 januari 2012, p. 14. (vermelding Erfgoeddag) . Katelijne Beerten, Gezocht uw verhaal over Lanakense dorpsdokters, Het belang Van Limburg – Het belang van Bilzen, 21 januari 2012, p. 8. (vermelding Erfgoeddag) . (DBS), Bib zoekt wielerhelden, Het Laatste Nieuws De Ring-Brussel, 24 januari 2012, p. 21. (vermelding Erfgoeddag) . (WO), Cultuurraad verovert Moerzeke Hamme, Gazet Van Antwerpen Waasland, 26 januari 2012, p. 16 . (vermelding Erfgoeddag) . Marijn Sillis, (geen titel), Gazet Van Antwerpen Mechelen, 27 januari 2012, p. -

Ensor to Permeke

06 • 10 • 2015 Ensor to Permeke A PASSION FOR BELGIAN ART BA cata Ensor 167x242 22/07/15 10:00 Page 1 ENTE VEILING mardi - dinsdag 06 • 10 • 2015 - 19.00 Ensor to Permeke A PASSION FOR BELGIAN ART 7 – 9, RUE ERNEST ALLARDSTRAAT (SABLON-ZAVEL) • B-1000 BRUXELLES - BRUSSEL T. +32 (0)2 511 53 24 • [email protected] WWW.BA-AUCTIONS.COM BA cata Ensor 167x242 22/07/15 10:00 Page 2 BA cata Ensor 167x242 22/07/15 10:00 Page 3 BA cata Ensor 167x242 22/07/15 10:00 Page 4 La collection Eric Drossart, le reflet d’une passion Lorsque je disputais la Coupe Davis dans les années soixante, et même au début de ma carrière chez Mc Cormack, je ne me connais- sais aucune affinité particulière avec l’Art. Tout a commencé lors de mon installation à Londres, au début des années quatre-vingt. J’y ai découvert le monde des galeries d’art, des ventes aux enchères et très vite cet univers fascinant s’est imposé à moi comme une évidence et devint une passion. Mon intérêt pour l’art belge, essentiellement celui de la fin du 19e siècle et du début du 20e siècle, répondait parfaitement à ma sensibilité naissante et à mon sentiment d’exilé. Dès 1991 j’ai donc commencé avec les encouragements de ma mère, qui adorait fouiner, à rechercher et à acquérir des œuvres d’artistes belges de cette période. Peu de temps après, j’ai eu la chance de rencontrer Sabine Taevernier qui est devenue, et qui est encore aujourd’hui, ma conseillère. -

Interes Ng Languages Facts About the Dutch Langua

www.dutchtrans.co.uk [email protected] Dutch Trans Tel: UK +44 20-80997921 Interes�ng languages facts about the Dutch langua The main language! There are many ques�ons in regards to the Flem- ish language and how is it different from Dutch. We will give you some Flemish language facts to clear things up. With three-fi�hs of the popula�on being na�ve speakers, Dutch is considered to be the majority language in Belgium. Dutch speakers mostly living on the Flemish Region have created the Dutch variety commonly referred to as "Flem- ish". Quick Flemish language facts The usage of the word "Flemish" to refer to the Dutch variety in Northern Belgium is con- sidered informal. Also, linguis�cally, the term "Flemish" is used in other different ways such as an indica�on of any local dialects in the Flanders region, as well as non-standard varia- �ons of the Dutch language in the provinces of French Flanders and West Flanders. 1 www.dutchtrans.co.uk [email protected] Dutch Trans Tel: UK +44 20-80997921 Dialects... The usage of the Flemish in reference to the Dutch language does not separate it from the Standard Dutch or the other dialects. That's why linguists avoid the term "Flemish" to refer to the Dutch Language preferring the usage of "Flemish Dutch", "Belgian Dutch" or "Southern Dutch". Flemish formally refers to the Flemish Region, which is one of the three official regions of the Kingdom of Belgium. Flemish Varia�ons! The Flemish region has four principal varia�ons of the Dutch language: East and West Flemish, Bra- ban�an and Limburgish. -

Belgian Identity Politics: at a Crossroad Between Nationalism and Regionalism

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2014 Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism Jose Manuel Izquierdo University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Human Geography Commons Recommended Citation Izquierdo, Jose Manuel, "Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2014. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2871 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Jose Manuel Izquierdo entitled "Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Geography. Micheline van Riemsdijk, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Derek H. Alderman, Monica Black Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Jose Manuel Izquierdo August 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Jose Manuel Izquierdo All rights reserved. -

Belgian Agriculture and Rural Environments the Spatial Dimension of Contemporary Problems and Challenges

Belgeo Revue belge de géographie 1-2-3-4 | 2000 Special issue: 29th International Geographical Congress Belgian agriculture and rural environments The spatial dimension of contemporary problems and challenges Etienne Van Hecke, Henk Meert and Charles Christians Publisher Société Royale Belge de Géographie Electronic version Printed version URL: http://belgeo.revues.org/14010 Date of publication: 30 décembre 2000 DOI: 10.4000/belgeo.14010 Number of pages: 201-218 ISSN: 2294-9135 ISSN: 1377-2368 Electronic reference Etienne Van Hecke, Henk Meert and Charles Christians, « Belgian agriculture and rural environments », Belgeo [Online], 1-2-3-4 | 2000, Online since 12 July 2015, connection on 01 October 2016. URL : http:// belgeo.revues.org/14010 ; DOI : 10.4000/belgeo.14010 This text was automatically generated on 1 octobre 2016. Belgeo est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Belgian agriculture and rural environments 1 Belgian agriculture and rural environments The spatial dimension of contemporary problems and challenges Etienne Van Hecke, Henk Meert and Charles Christians With thanks to Messrs F. Huyghe and F. Beyers of the Belgian Farmers’ Association (Louvain), J.M. Bouquiaux of the Centre d’économie agricole (Brussels) Introduction 1 For many years, the countryside was in relation to the city what agriculture was in relation to industry and services. This dichotomy has now become a thing of the past. Until recently, the approach to rural studies was mainly threefold; morphological, the study of rural landscapes and their genesis; functional, involving the study of agriculture, the sector which supports rural areas; and socio-economic, examining rural decline caused by the crisis in agriculture and the migration away from remote countryside areas. -

Continuum 119 a Belgian Art Perspective

CONTINUUM 119 A BELGIAN ART PERSPECTIVE OFF-PROGRAM GROUP SHOW 15/04/19 TO 31/07/19 Art does not belong to anyone, it usually passes on from one artist to the next, from one viewer to the next. We inherit it from the past when it served as a cultural testimony to who we were, and we share it with future generations, so they may understand who we are, what we fear, what we love and what we value. Over centuries, civilizations, societies and individuals have built identities around art and culture. This has perhaps never been more so than today. As an off-program exhibition, I decided to invite five Belgian artists whose work I particularly like, to answer back with one of their own contemporary works to a selection of older works that helped build my own Belgian artistic identity. In no way do I wish to suggest that their current work is directly inspired by those artists they will be confronted with. No, their language is mature and singular. But however unique it may be, it can also be looked at in the context of the subtle evolution from their history of art, as mutations into new forms that better capture who these artists are, and the world they live in. Their work can be experienced within an artistic continuum, in which pictorial elements are part of an inheritance, all the while remaining originally distinct. On each of these Belgian artists, I imposed a work from the past, to which they each answered back with a recent work of their own. -

G Er T Ja Nv an R Oo Ij

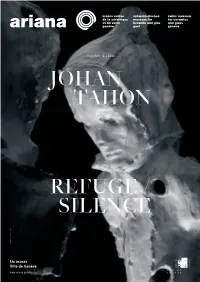

28.9.2019–5.4.2020 JOHAN TAHON REFUGE / SILENCE Photographie : Gert Jan van Rooij Press Kit 16 September 2019 Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 Press visits on request only Exhibition preview Friday 27 September 2019 at 6pm Musée Ariana Swiss Museum for Ceramics and Glass 10, avenue de la Paix 1202 Geneva - Switzerland Press kit available at “Presse”: www.ariana-geneve.ch Visuals, photos on request: [email protected] Un musée Ville de Genève www.ariana-geneve.ch Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 CONTENTS Johan Tahon. REFUGE/SILENCE p. 3 Biography of Johan Tahon p. 4 Events p. 8 Practical information p. 9 2 Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 J OHAN T AHON. REFUGE/SILENCE The Musée Ariana is proud to present Johan Tahon. REFUGE/SILENCE, in partnership with the Kunstforum gallery in Solothurn, from 28 September 2019 to 5 April 2020 in the space dedicated to contemporary creation. Johan Tahon, internationally renowned Belgian artist, is exhibiting a strong and committed body of work that reveals his deep connection with the ceramic medium. In the space devoted to contemporary creation, visitors enter a mystical world inhabited by hieratic monks, leading them into a second gallery where, in addition to the figures, pharmacy jars or albarelli are displayed. A direct reference to the history of faience, the ointments, powders and medicines contained in such vessels were intended to heal both body and soul. A sensitive oeuvre reflecting the human condition Johan Tahon’s oeuvre evolves in an original and individual way. -

Untitled for the Exhibition Body Talk Presented at WIELS, Brussels 2015

1 Inhoudstafel Inhoudstafel ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Feast of Fools. Bruegel herontdekt ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Meer dan alleen een tentoonstelling .................................................................................................................................... 6 Titel ........................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Kunstwerken ‘Feast of Fools. Bruegel herontdekt’............................................................................................................ 8 Bruiklenen ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 8 1. Introductie ............................................................................................................................................................................ 8 2. Back to the Roots ............................................................................................................................................................ 8 3. Everybody Hurts ............................................................................................................................................................. -

Press Release Brafa 2018

PRESS RELEASE BRAFA 2018 Galerie Oscar De Vos is pleased to announce the selected artworks for BRAFA 2018 at Tour & Taxis, Brussels. The exhibition focuses on quality works of MODERN BELGIAN ART FROM ABOUT 1890-1930. More than 40 oil paintings and a fine selection of works on paper and sculptures (marble , bronze, plaster) will expose the wide-ranging art of the Latem School is the collection will show how radically the art movements in Belgian, and even internationally, have been changed in such a short time period. Most of the artworks belonged to private collections and these artworks will be – even for the first time – on show during BRAFA 2018 since decades. Special attention is given to: Kneeling youth (1896) with gold leaf patina by George Minne Nasturtiums (1901) by Emile Claus Rest after the haymaking (1902) by Emile Claus Spring morning in Wales (1920) by Valerius De Saedeleer Wrapped up peasant (1910) by Gustave Van de Woestyne Playing boy in the snow (1918) by Frits Van den Berghe The lumberman (1930) by Gust. De Smet and the magnum opus of Frits Van den Berghe: The companions (1932). These paintings have been exhibited in major international museums, among others in Antwerp, Brussels, Ghent, Leningrad, Moscow, Oslo, Stockholm and Tokyo. Museum catalogues, scientific publications and articles illustrate and confirm the importance of these artworks in specific and the Latem School artists in general. These Belgian avant-garde artists were protagonists of international art movements such as Impressionism, Symbolism, Expressionism and Surrealism. Over the last fifty years, Galerie Oscar De Vos has established its name in this specialized domain, contributing to international museum exhibitions and publications, and participating in international art fairs.