Belgian Identity Politics: at a Crossroad Between Nationalism and Regionalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Challenges for Flemish Agriculture and Horticulture

LARA '18 LARA '18 CHALLENGES FOR FLEMISH AGRICULTURE AND HORTICULTURE DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE & FISHERIES CHALLENGES FOR FLEMISH AGRICULTURE AND HORTICULTURE The seventh edition of the Flemish Agriculture Report (LARA) was published in 2018. The report deals with the challenges for Flemish agriculture and horticulture. At the same time, it pro- vides a detailed description of the subsectors. A SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) also takes place per subsector. Between the chapters, experts from policy, research and civil society give their vision on challenges faced by Flemish agriculture and how the sector should deal with them. This is a translation of the summary of the report. You’ll find the entire report in Dutch on www.vlaanderen.be/landbouwrapport. © Flemish Government, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries Platteau J., Lambrechts G., Roels K., Van Bogaert T., Luypaert G. & Merckaert B. (eds.) (2019) Challenges for Flemish agriculture and horticulture, Agriculture Report 2018, Summary, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brussels. D/2019/3241/075 1 CURRENT SITUATION AGRICULTURE IS CHARACTERISED BY ECONOMIES OF SCALE, SPECIALISATION, DIVERSIFICATI- ON AND INNOVATION In 2017, Flanders had 23,225 agricultural businesses, 78% of which were of a professional nature. Compa- red to 2007, the number of agricultural holdings has decreased by slightly more than a quarter, a decrease of 3% per year on average. In particular smaller farms stop their activities, which leads to a constant increase in scale. In 2017, agriculture and horticulture as a whole covered an area of 610,971 hectares. Thereof, the largest part is accounted for by fodder crops (maize and meadows) and cereals, with 56% and 21% respectively. -

Landslides in Belgium—Two Case Studies in the Flemish Ardennes and the Pays De 20 Herve

Landslides in Belgium—Two Case Studies in the Flemish Ardennes and the Pays de 20 Herve Olivier Dewitte, Miet Van Den Eeckhaut, Jean Poesen and Alain Demoulin Abstract Most landslides in Belgium, and especially the largest features, do not occur in the Ardenne, where the relief energy and the climate conditions seem most favourable. They appear in regions located mainly north of them where the lithology consists primarily of unconsolidated material. They develop on slopes that are relatively smooth, and their magnitude is pretty large with regard to that context. An inventory of more than 300 pre-Holocene to recent landslides has been mapped. Twenty-seven percent of all inventoried landslides are shallow complex landslides that show signs of recent activity. The remaining landslides are deep-seated features and rotational earth slides dominate (n > 200). For such landslides, the average area is 3.9 ha, but affected areas vary from 0.2 to 40.4 ha. The exact age of the deep-seated landslides is unknown, but it is certain that during the last century no such landslides were initiated. Both climatic and seismic conditions during the Quaternary may have triggered landslides. The produced landslide inventory is a historical inventory containing landslides of different ages and triggering events. Currently, only new shallow landslides or reactivations within existing deep-seated landslides occur. The focus on the Hekkebrugstraat landslide in the Flemish Ardennes allows us to understand the recent dynamics of a large reactivated landslide. It shows the complexity of the interactions between natural and human-induced processes. The focus on the Pays the Herve allows for a deeper understanding of landslide mechanisms and the cause of their origin in natural environmental conditions. -

Sample Chapter

Copyright material – 9781137029607 © Kris Deschouwer 2009, 2012 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First edition 2009 This edition published 2012 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries ISBN: 978-1-137-03024-5 hardback ISBN: 978-1-137-02960-7 paperback This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. -

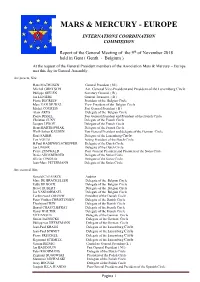

Mars & Mercury

MARS & MERCURY - EUROPE INTERNATIONS COORDINATION COMMISSION Report of the General Meeting of the 9th of November 2018 held in Gent ( Genth - Belgium ) At the request of the General President members of the Association Mars & Mercury – Europe met this day in General Assembly. Are present, Sirs: Hans MATHIJSEN General President ( Nl ) Michel GRETSCH Act. General Vice-President and President of the Luxemburg Circle Philippe GIELEN Secretary General. ( B ) Jan LENIÈRE General Treasurer. ( B ) Pierre DEGREEF President of the Belgian Circle Marc VAN DE WAL Vice- President of the Belgian Circle Michel COURTIN Past General President ( B ) Alain ARYS Delegate of the Belgian Circle Pierre DISSEL Past General President and President of the French Circle Christian CUNY Delegate of the French Circle Jacques LEROY Delegate of the French Circle Henri BARTKOWIAK Delegate of the French Circle Wolf-Arthur KALDEN Past General President and delegate of the German Circle René FABER Delegate of the Luxemburg Circle Ton VOETS Acting President of the Dutch Circle H.Paul HADEWEG SCHEFFER Delegate of the Dutch Circle Jan UNGER Delegate of the Dutch Circle Pierre ZUMWALD Past General President and President of the Swiss Circle Denis AUGSBURGER Delegate of the Swiss Circle Olivier CINGRIA Delegate of the Swiss Circle Jean-Marc PETERMANN Delegate of the Swiss Circle Are excused, Sirs: Ronald CAZAERCK Auditor Marc DE BRACKELEER Delegate of the Belgian Circle Eddy DE BOCK Delegate of the Belgian Circle Hervé HUBERT Delegate of the Belgian Circle Jos VANDORMAEL Delegate -

Executive and Legislative Bodies

Published on Eurydice (https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice) Legislative and executive powers at the various levels Belgium is a federal state, composed of the Communities and the Regions. In the following, the federal state structure is outlined and the Government of Flanders and the Flemish Parliament are discussed. The federal level The legislative power at federal level is with the Chamber of Representatives, which acts as political chamber for holding government policy to account. The Senate is the meeting place between regions and communities of the federal Belgium. Together they form the federal parliament. Elections are held every five years. The last federal elections took place in 2014. The executive power is with the federal government. This government consists of a maximum of 15 ministers. With the possible exception of the Prime Minister, the federal government is composed of an equal number of Dutch and French speakers. This can be supplemented with state secretaries. The federal legislative power is exercised by means of acts. The Government issues Royal Orders based on these. It is the King who promulgates federal laws and ratifies them. The federal government is competent for all matters relating to the general interests of all Belgians such as finance, defence, justice, social security (pensions, sickness and invalidity insurance), foreign affairs, sections of health care and domestic affairs (the federal police, oversight on the police, state security). The federal government is also responsible for nuclear energy, public-sector companies (railways, post) and federal scientific and cultural institutions. The federal government is also responsible for all things that do not expressly come under the powers of the communities and the regions. -

Flemish Art 1880–1930

COMING FLEMISH ART 1880–1930 EDITOR KATHARINA VAN CAUTEREN HOME WITH ESSAYS BY ANNE ADRIAENS-PANNIER PATRICK BERNAUW PIET BOYENS KLAAS COULEMBIER JOHAN DE SMET MARK EYSKENS DAVID GARIFF LEEN HUET FERNAND HUTS PAUL HUVENNE PETER PAUWELS CONSTANTIJN PETRIDIS NIELS SCHALLEY HERWIG TODTS KATHARINA VAN CAUTEREN LUC VAN CAUTEREN SVEN VAN DORST CATHÉRINE VERLEYSEN Hubert Malfait Home from the Fields, 1923-1924 Oil on canvas, 120 × 100 cm COURTESY OF FRANCIS MAERE FINE ARTS CONTENTS 7 PREFACE 211 JAMES ENSOR’S KATHARINA VAN CAUTEREN WHIMSICAL QUEST FOR BLISS HERWIG TODTS 9 PREFACE FERNAND HUTS 229 WOUTERS WRITINGS 13 THE ROOTS OF FLANDERS HERWIG TODTS KATHARINA VAN CAUTEREN 253 EDGARD TYTGAT. 65 AUTHENTIC, SOUND AND BEAUTIFUL. ‘PEINTRE-IMAGIER’ THE RECEPTION OF LUC VAN CAUTEREN FLEMISH EXPRESSIONISM PAUL HUVENNE 279 CONSTANT PERMEKE. THE ETERNAL IN THE EVERYDAY 79 THE MOST FLEMISH FLEMINGS PAUL HUVENNE WRITE IN FRENCH PATRICK BERNAUW 301 GUST. DE SMET. PAINTER OF CONTENTMENT 99 A GLANCE AT FLEMISH MUSIC NIELS SCHALLEY BETWEEN 1890 AND 1930 KLAAS COULEMBIER 319 FRITS VAN DEN BERGHE. SURVEYOR OF THE DARK SOUL 117 FLEMISH BOHÈME PETER PAUWELS LEEN HUET 339 ‘PRIMITIVISM’ IN BELGIUM? 129 THE BELGIAN LUMINISTS IN AFRICAN ART AND THE CIRCLE OF EMILE CLAUS FLEMISH EXPRESSIONISM JOHAN DE SMET CONSTANTIJN PETRIDIS 149 BENEATH THE SURFACE. 353 LÉON SPILLIAERT. THE ART OF THE ART OF THE INDEFINABLE GUSTAVE VAN DE WOESTYNE ANNE ADRIAENS-PANNIER SVEN VAN DORST 377 THE EXPRESSIONIST IMPULSE 175 VALERIUS DE SAEDELEER. IN MODERN ART THE SOUL OF THE LANDSCAPE DAVID GARIFF PIET BOYENS 395 DOES PAINTING HAVE BORDERS? 195 THE SCULPTURE OF MARK EYSKENS GEORGE MINNE CATHÉRINE VERLEYSEN 6 PREFACE Dear Reader, 7 Just so you know, this book is not the Bible. -

Born out of Rebellion: the Netherlands from the Dutch Revolt to the Eve of World War I: Ulrich Tiedau | University College London

09/25/21 DUTC0003: Born out of Rebellion: The Netherlands from the Dutch Revolt to the Eve of World War I: Ulrich Tiedau | University College London DUTC0003: Born out of Rebellion: The View Online Netherlands from the Dutch Revolt to the Eve of World War I: Ulrich Tiedau Arblaster P, A History of the Low Countries, vol Palgrave essential histories (Palgrave Macmillan 2006) Blom, J. C. H. and Lamberts, Emiel, History of the Low Countries (Berghahn Books 1999) Boogman JC, ‘Thorbecke, Challenge and Response’ (1974) 7 Acta Historiae Neerlandicae 126 Bornewasser JA, ‘Mythical Aspects of Dutch Anti-Catholicism in the 19th Century’, Britain and the Netherlands: Vol.5: Some political mythologies (Martinus Nijhoff 1975) Boxer, C. R., The Dutch Seaborne Empire, 1600-1800, vol Pelican books (Penguin 1973) Cloet M, ‘Religious Life in a Rural Deanery in Flanders during the 17th Century. Tielt from 1609 to 1700’ (1971) 5 Acta Historiae Neerlandica 135 Crew, Phyllis Mack, Calvinist Preaching and Iconoclasm in the Netherlands, 1544-1569, vol Cambridge studies in early modern history (Cambridge University Press 1978) Daalder H, ‘The Netherlands: Opposition in a Segmented Society’, Political oppositions in western democracies (Yale University Press 1966) Darby, Graham, The Origins and Development of the Dutch Revolt (Routledge 2001) Davis WW, Joseph II: An Imperial Reformer for the Austrian Netherlands (Nijhoff 1974) De Belder J, ‘Changes in the Socio-Economic Status of the Belgian Nobility in the 19th Century’ (1982) 15 Low Countries History Yearbook 1 Deursen, Arie Theodorus van, Plain Lives in a Golden Age: Popular Culture, Religion, and Society in Seventeenth-Century Holland (Cambridge University Press 1991) Dhont J and Bruwier M, ‘The Industrial Revolution in the Low Countries’, The emergence of industrial societies: Part 1, vol The Fontana economic history of Europe (Fontana 1973) Emerson B, Leopold II of the Belgians: King of Colonialism (Weidenfeld and Nicolson) Fishman, J. -

European Network Operations Plan 2021 Rolling Seasonal Plan Edition 34 2 July 2021

European Network Operations Plan 2021 Rolling Seasonal Plan Edition 34 2 July 2021 FOUNDING MEMBER NETWORK SUPPORTING EUROPEAN AVIATION MANAGER EUROCONTROL Network Management Directorate DOCUMENT CONTROL Document Title European Network Operations Plan Document Subtitle Rolling Seasonal Plan Document Reference Edition Number 34 Edition Validity Date 02-07-2021 Classification Green Status Released Issue Razvan Bucuroiu (NMD/ACD) Author(s) Stéphanie Vincent (NMD/ACD/OPL) Razvan Bucuroiu (NMD/ACD) Contact Person(s) Stéphanie Vincent (NMD/ACD/OPL) Edition Number: 34 Edition Validity Date: 02-07-2021 Classification: Green Page: i Page Validity Date: 02-07-2021 EUROCONTROL Network Management Directorate EDITION HISTORY Edition No. Validity Date Reason Sections Affected 0 12/10/2020 Mock-up version All 1 23/10/2020 Outlook period 26/10/20-06/12/20 As per checklist 2 30/10/2020 Outlook period 02/11/20-13/12/20 As per checklist 3 06/11/2020 Outlook period 09/11/20-20/12/20 As per checklist 4 13/11/2020 Outlook period 16/11/20-27/12/20 As per checklist 5 20/11/2020 Outlook period 23/11/20-03/01/21 As per checklist 6 27/11/2020 Outlook period 30/11/20-10/01/21 As per checklist 7 04/12/2020 Outlook period 07/12/20-17/01/21 As per checklist 8 11/12/2020 Outlook period 14/12/20-24/01/21 As per checklist 9 18/12/2020 Outlook period 21/12/20-31/01/21 As per checklist 10 15/01/2021 Outlook period 18/01/21-28/02/21 As per checklist 11 22/01/2021 Outlook period 25/01/21-07/03/21 As per checklist 12 29/01/2021 Outlook period 01/02/21-14/03/21 As per checklist -

Social Cleavages, Political Institutions and Party Systems: Putting Preferences Back Into the Fundamental Equation of Politics A

SOCIAL CLEAVAGES, POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS AND PARTY SYSTEMS: PUTTING PREFERENCES BACK INTO THE FUNDAMENTAL EQUATION OF POLITICS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Heather M. Stoll December 2004 c Copyright by Heather M. Stoll 2005 All Rights Reserved ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. David D. Laitin, Principal Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Beatriz Magaloni-Kerpel I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Morris P. Fiorina Approved for the University Committee on Graduate Studies. iii iv Abstract Do the fundamental conflicts in democracies vary? If so, how does this variance affect the party system? And what determines which conflicts are salient where and when? This dis- sertation explores these questions in an attempt to revitalize debate about the neglected (if not denigrated) part of the fundamental equation of politics: preferences. While the com- parative politics literature on political institutions such as electoral systems has exploded in the last two decades, the same cannot be said for the variable that has been called social cleavages, political cleavages, ideological dimensions, and—most generally—preferences. -

From an Institutionalized Manifest Catholic to a Latent Christian Pillar

Karel Dobbelaere1 Оригинални научни рад Catholic University of Leuven and University of Antwerp, Belgium UDK 322(493) RELIGION AND POLITICS IN BELGIUM: FROM AN INSTITUTIONALIZED MANIFEST CATHOLIC TO A LATENT CHRISTIAN PILLAR Abstract After having described the historical basis of the process of pillarization in Belgium, the author explains the emergence of the Catholic pillar as a defence mechanism of the Catholic Church and the Catholic leadership to protect the Catholic flock from sec- ularization. He describes the different services the Catholic pillar was offering for its members and the development of Belgium as a state based on three pillars: the catho- lic, the socialist and the liberal one that were all three institutionalized. This structure meant that Belgium was rather a segregated country that was vertically integrated. In the sixties of last century, the pillar was confronted with a growing secularization of the population, which forced the leadership of the pillar to adapt the collective con- sciousness: the Catholic credo, values and norms were replaced by so-called typical values of the Gospel integrated in what is called a Socio-Cultural Christianity. Under the impact of the changing economic situation, the politicization of the Flemish ques- tion and the emergence of Ecologist parties, the Christian pillar had to adapt its serv- ices and is now based on clienteles rather than members. Only in the Flemish part of Belgium is it still an institutionalized pillar. Key words: Collective Consciousness, Pillarization; Pillar; Institutionalized Pillar, Solidarity: Mechanical and Organic Solidarity,Vertical pluralism, Secularization. The concept of ‘pillar’ and the process of ‘pillarization’ are translations of the Dutch terms zuil and zuilvorming to describe the special structure of vertical pluralism typical of Dutch society. -

The Parliaments of Belgium and Their International

THE PARLIAMENTS OF BELGIUM AND THEIR INTERNATIONAL POWERS This brochure aims to provide readers with a bird’s eye per- spective of the distribution of power in Federal Belgium in plain language. Particular emphasis goes out to the role of the Parliamentary assemblies in international affairs. Federal Belgium as we now know it today is the result of a peaceful and gradual political development seeking to give the country’s various Communities and Regions wide-ranging self-rule. This enables them to run their own policies in a way that is closely geared to the needs and wishes of their own citizens. In amongst other elements, the diversity and self-rule of the Regions and Communities manifest themselves in their own Parliaments and Govern- ments. Same as the Federal Parliament, each of these Regional Parliamentary assemblies has its own powers, is able to autonomously adopt laws and regulations for its territory and population and ratify international treaties in respect of its own powers. HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT Belgium became an independent state in 1830 with a bicam- eral Parliament (Chamber of Representatives and Senate) and a Government. The only administrative language at the time was French. Dutch and German were only gradually recognised as administrative languages. The four linguistic regions (Dutch, French, German and the bilingual Region of Brussels-Capital) were established in 1962. Over the course of the second half of the twentieth century came the growing awareness that the best way forward was for the various Communities to be given the widest possi- ble level of self-rule, enabling them to make their own deci- sions in matters such as culture and language. -

Belgian Polities in 1988 Content 1. the Painstaking Forming of The

Belgian Polities in 1988 Content 1. The painstaking forming of the Martens VIII Cabinet 303 A. The forming of regional governments complicates the making of a national cabinet . 303 B. The information mission of Dehaene 305 C. Dehaene's formation mission . 305 D. Martens VIII wins vote of confidence in Parliament 308 ll. Phase one of the constitutional reform 309 A. The amendment of seven constitutional articles 309 B. The special August 8, 1988 Act. 310 C. The bill on the language privileges . 312 111. The second phase of the constitutional reform 314 A. The new politica! status of the Brussels Region 314 B. The Arbitration Court . 315 C. The regional financing law. 315 D. Consultation and meditation 316 IV. The municipal elections, the government reshuffle and the debt of the larger cities 317 A. The municipal elections, Fourons and municipalities with special language status 317 B. The government reshuffle . 318 C. The debt of the larger cities 318 V. The social and economie policy of the Martens VIII cabinet 319 A. The 1988 and 1989 budgets 319 B. Tax reform 320 C. Labor Relations-Public Service Strikes-Health lnsurance 321 Vl. Foreign Affairs and Defense. 323 A. Foreign Affairs 323 B. Defense . 325 VII. lnternal politica! party developments. 325 Belgian polities in 1988 by Ivan COUTTENIER, Licentiate in Politica) Science During the first four months of 1988, Belgium witnessed the painstaking for mation of the Martens VIII center-left Cabinet. In October 1987, the Christian Democratic-Liberal Martens VI Cabinet had been forced to resign over the pe rennial Fourons affairs.