View Full Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allied Painting Secures Delaware Memorial Bridge Contracts

Project Preview Allied Painting Secures Delaware MemorialBy Alyssa Gallagher, Paint Bridge BidTracker Contracts he Delaware River Gulf War. Allied secured a and Bay Authority contract of $951,800 to recoat T awarded two con- 603,000 square feet of steel on tracts with a combined value the First Structure of $2,853,600 to Allied (Northbound) and a contract Painting, Inc. (Franklinville, of $1,901,800 to recoat NJ), SSPC-QP 1 and QP 2 cer- 659,500 square feet of steel on tified, to clean and recoat steel the Second Structure surfaces on the west girder (Southbound). The steel, spans of the Delaware including the interior of piers, Memorial Bridge. The 10,765- platforms, and ladders, will be foot-long twin spans connect Photo courtesy of Delaware River and Bay Authority spot power-tool cleaned New Castle, DE, and Pennsville, NJ, over the Delaware River. (SSPC-SP 3), spot-primed, and coated with a 4-coat moisture- The bridge is dedicated to veterans who gave their lives in cured urethane system. The contractor will employ a third- World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the party coatings inspector as part of the quality control plan. Click our Reader e-Card at paintsquare.com/ric www.paintsquare.com 70 JPCL July 2010 Crosno Construction to Rehabilitate Three Tanks Crosno Construction Inc. (San Luis Obispo, CA) secured a 100%-solids elastomeric polyurethane system. The project contract of $569,501.04 with the City of Sunnyvale, CA, to also includes the application of an epoxy-polyurethane sys- repair and reline three 60-foot-diameter by 24-foot-high steel tem to exterior surfaces. -

It's the Way to Go at the Peace Bridge

The coupon is not an invoice. If you Step 3 Read the customer guide New Jersey Highway Authority Garden State Parkway are a credit card customer, you don’t carefully. It explains how to use E-ZPass have to worry about an interruption and everything else that you should know New Jersey Turnpike Authority New Jersey Turnpike in your E-ZPass service because we about your account. Mount your tag and New York State Bridge Authority make it easy for you by automatically you’re on your way! Rip Van Winkle Bridge replenishing your account when it hits Kingston-Rhinecliff Bridge a low threshold level. Mid-Hudson Bridge Newburgh-Beacon Bridge For current E-ZPass customers: Where it is available. Bear Mountain Bridge If you already have an E-ZPass tag from E-ZPass is accepted anywhere there is an E-ZPass logo. New York State Thruway Authority It’s the Way another toll agency such as the NYS This network of roads aids in making it a truly Entire New York State Thruway including: seamless, regional transportation solution. With one New Rochelle Barrier Thruway, you may use your tag at the account, E-ZPass customers may use all toll facilities Yonkers Barrier Peace Bridge in an E-ZPass lane. Any where E-ZPass is accepted. Tappan Zee Bridge to Go at the NYS Thruway questions regarding use of Note: Motorists with existing E-ZPass accounts do not Spring Valley (commercial vehicle only) have to open a new or separate account for use in Harriman Barrier your tag must be directed to the NYS different states. -

EM Directions.Ai

TO: COMPANY: FAX: FROM: 100 Melrose Ave., Cherry Hill, NJ 08003 Driving Directions tel (800) 223-1376 fax (856) 428-5477 FROM NEW JERSEY: From Northern NJ: From Southern NJ: Take I-295 South to Exit #31 for Woodcrest Station. Take I-295 North to Exit #31 for Woodcrest Station. At the end of the exit ramp, turn left at the traffic light. At the end of the exit ramp, turn left at the traffic light. Our building is immediately on the left (about 100 yards). Our building is immediately on the left (about 100 yards). FROM PENNSYLVANIA: From Ben Franklin Bridge: From Walt Whitman Bridge: Cross the Ben Franklin Bridge into New Jersey. Cross the Walt Whitman Bridge into New Jersey. Take Rt. 676 East until you reach Route 42. Take Route 42 South until you reach I-295 North. Take Rt. 42 South until you reach I-295 North. Take I-295 North to Exit #31 for Woodcrest Station. Take I-295 North to Exit #31 for Woodcrest Station. At the end of the exit ramp, turn left at the traffic light. At the end of the exit ramp, turn left at the traffic light. Our building is immediately on the left (about 100 yards). Our building is immediately on the left (about 100 yards). FROM DELAWARE: Cross the Delaware Memorial Bridge into New Jersey. Take I-295 North to Exit #31 for Woodcrest Station. At the end of the exit ramp, turn left at the traffic light. Our building is immediately on the left (about 100 yards). -

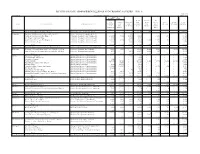

Receipts of State-Administered Toll

RECEIPTS OF STATE-ADMINISTERED TOLL ROAD AND CROSSING FACILITIES - 1996 1/ TABLE SF-3B OCTOBER 1997 ( THOUSANDS OF DOLLARS ) SHEET 1 OF 2 BALANCES BEGINNING OF YEAR 2/ RESERVES ROAD CONCES- NET FOR RESERVES HIGHWAY- AND SIONS INCOME MISCEL- BOND TOTAL STATE NAME OF FACILITY OPERATING AUTHORITY CONSTRUC- FOR USER CROSSING AND FROM LANEOUS PROCEEDS RECEIPTS TION, DEBT REVENUES TOLLS RENTALS INVEST- OPERATION, SERVICE MENTS ETC. Alaska Alaska Ferry (Marine Highway) System Alaska Department of Public Works - - - 15,200 7,800 - 77,671 - 100,671 California Mid-State Toll Road, State Routes 125, 91, & 57 Private Operators (California DOT) 3/ - - 837 - - - - - 837 Northern San Francisco Bay Bridges 4/ California Transportation Commission 242,000 4,962 23,680 56,256 - 14,951 237 - 95,124 San Diego-Coronado Bridge California Transportation Commission 10,564 - 3,889 6,024 - 572 4 - 10,489 Southern San Francisco Bay Bridges 5/ California Transportation Commission 250,523 6,958 26,413 72,670 3,100 14,893 285 - 117,361 Vincent Thomas Bridge California Transportation Commission 10,467 - 3,169 2,650 - 621 1 - 6,441 Total 513,554 11,920 57,988 137,600 3,100 31,037 527 - 230,252 Connecticut Rockyhill-Glastonbury and Chester-Hadlyme Ferries Connecticut Department of Transportation - - 186 201 - - - - 387 Delaware Delaware Memorial Bridge and Cape May-Lewes Ferry Delaware River and Bay Authority 62,427 8,848 - 53,725 4,004 4,843 387 65,305 128,264 John F. Kennedy Memorial Highway and SR-1 Toll Road Delaware Transportation Authority 4,938 - 6,075 48,337 2,068 -

North Atlantic Ocean

210 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 6 26 SEP 2021 75°W 74°30'W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 3—Chapter 6 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml Trenton 75°30'W 12314 P ENNSYLV ANIA Philadelphia 40°N 12313 Camden E R I V R E R Wilmington A W A L E D NEW JERSEY 12312 SALEM RIVER CHESAPEAKE & DELAWARE CANAL 39°30'N 12304 12311 Atlantic City MAURICE RIVER DELAWARE BAY 39°N 12214 CAPE MAY INLET DELAWARE 12216 Lewes Cape Henlopen NORTH ATL ANTIC OCEAN INDIAN RIVER INLET 38°30'N 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 6 ¢ 211 Delaware Bay (1) This chapter describes Delaware Bay and River and (10) Mileages shown in this chapter, such as Mile 0.9E their navigable tributaries and includes an explanation of and Mile 12W, are the nautical miles above the Delaware the Traffic Separation Scheme at the entrance to the bay. Capes (or “the Capes”), referring to a line from Cape May Major ports covered are Wilmington, Chester, Light to the tip of Cape Henlopen. The letters N, S, E, or Philadelphia, Camden and Trenton, with major facilities W, following the numbers, denote by compass points the at Delaware City, Deepwater Point and Marcus Hook. side of the river where each feature is located. Also described are Christina River, Salem River, and (11) The approaches to Delaware Bay have few off-lying Schuylkill River, the principal tributaries of Delaware dangers. River and other minor waterways, including Mispillion, (12) The 100-fathom curve is 50 to 75 miles off Delaware Maurice and Cohansey Rivers. -

Support Tolls, Support Infrastructure Investment, Support Jobs

The Time For Tolls Is Now – Support Tolls, Support Infrastructure Investment, Support Jobs I am writing to express my support for HB 7202 in hopes that we will finally see toll collecting devices added to Connecticut’s various roadways throughout the state. Many will decry the measure as simply another tax. But it has never been more important that our state conduct its taxation in a manner that is fair and consistent when considering how our neighboring states choose to enforce their taxation methods. Attached to my letter, you will find my EZ Pass toll statements for 2018. What you will see is my family of 4 drivers paid almost $1400 in roadway and bridge tolls to the states of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts for the period covered by the statements. In light of the proliferation of toll booths up and down the east coast, I am befuddled to understand why we continue to allow drivers from other states to use Connecticut’s roadways without paying for their fair share. Enough is enough. Roadway tolls have the potential to more properly balance transportation project revenue sources with the parties that use those infrastructure assets the most. Roadway tolls have the potential to reduce congestion on our clogged highways. But the biggest reason to support roadway tolls is to rebuild Connecticut with bigger and better roadways while creating a stream of new good paying construction jobs in the process. Yes, I believe roadway tolls are a plus for our state, a big plus. And YES, I AM READY TO PAY TOLLS! I have but two simple requests. -

Salinity of the Delaware Estuary

Salinity of the Delaware Estuary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1586-B Prepared in cooperation with the City of Philadelphia and the State of Delaware \ Salinity of the Delaware Estuary By BERNARD COHEN and LEO T. McCARTHY, JR. HYDROLOGY OF TIDAL STREAMS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1586-B Prepared in cooperation with the City of Philadelphia and the State of Delaware UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTJIN.G OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1962 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.G. CONTENTS Page. Abstract- __-.___-_______.___.._____________________ Bl Introduction. ___________________________________________________ 1 Acknowledgments.______________________________________________ 3 Previous investigations___________________________________________ 4 Field program_________________________________________________ 4 Chemical characteristics of the water________________________________ 6 Variation in concentration and movement of chloride _____ _ ___________ 9 Effects of fresh- and salt-water inflow on distribution of salinity, __________ 20 Cross-sectional studies.____________________________________________ 29 Frequency of occurrence of chloride concentrations ____________________ 32 Effects of hurricanes on salmity___---___--___-_-_-_____--____-______ 33 Summary_______________________________________________________ 39 References____________________________________________________ -

DIRECTIONS from BALTIMORE • Take Interstate 95 Northeast (Kennedy Memorial Highway) for Approximately 50 to 55 Minutes

DIRECTIONS FROM BALTIMORE • Take Interstate 95 Northeast (Kennedy Memorial Highway) for approximately 50 to 55 minutes. (It is about 56 miles from Baltimore to the exit for Delaware Park.) • Leave Interstate 95 at Exit 4B (Stanton, Churchman's Road). • You are now on Delaware Route 1/Route 7 headed North. Continue directly ahead for approximately 1 1/2 miles or 5 traffic lights. (After approximately 1/2 a mile the designation as Route 1 ends and the road becomes Route4/Route 7.) • Turn left at the fifth traffic light. This is Delaware Park Boulevard. • Follow the road past Slot Valet parking, past Racetrack Valet parking, continue following the road over the White Clay Creek the Clubhouse is on your left hand side. FROM CHESAPEAKE BAY BRIDGE • Take Route 301 North to Middletown (Approximately 40 minutes or 45 miles). •In Middletown take 299 East for approximately 1 1/2 miles to Route 1/Route 13. • Take Routes 1/13 North over the new Bridge over the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal at St. Georges (Approximately 10 Minutes or 10 Miles). •Follow Route 1 to the Christiana Mall area. • You are now on Delaware Route 1/Route 7 headed North. Continue directly ahead for approximately 1 1/2 miles or 5 traffic lights. (After approximately 3/4 of a mile the designation as Route 1 ends and the road becomes Route4/Route 7. It is the same road just different numbers.) •Turn left at the fifth traffic light. This is Delaware Park Boulevard. • Follow the road past Slot Valet parking, past Racetrack Valet parking, continue following the road over the White Clay Creek the Clubhouse is on your left hand side. -

Nj Turnpike Interstate 295 Delaware Memorial Bridge

Directions: NJ TURNPIKE Take NJ Turnpike south to exit 3. After toll, follow signs for Route 168 south. Continue for one mile to traffic light and turn right on Route 544 & Route 41 south (Clements Bridge Road). Continue on Clements Bridge Road to 2nd traffic light and bear right (McDonalds) onto Route 544. Proceed to sixth light, bear right onto Cooper Street. Continue 4/10 mile to next light (Intersection of Cooper Street and Delsea Drive). Turn left and continue about 2 miles to second light (Bankbridge Road). Turn right onto Bankbridge Road. Follow Bankbridge to first traffic light and turn left (Tanyard Road). Continue ¼ mile to bottom of hill and GCIT will be on the left. INTERSTATE 295 Take 295 South to Route 42 South (follow signs to Atlantic City Expressway). Follow 42 South to the second exit (Route 55 South). Follow Route 55 South to 2nd exit (56B Route 47). At the first light take a left (Bankbridge Road.) Follow Bankbridge to first traffic light and turn left (Tanyard Road). Continue ¼ mile to bottom of hill and GCIT will be on the left. DELAWARE MEMORIAL BRIDGE Take Interstate 295 north to exit 21 Delaware Street (@30 minutes). Continue on Delaware Street through Woodbury. Turn Right at second traffic light onto Evergreen Avenue. Travel one block to next light and turn left onto Egg Harbor Road (Mobil Station). Proceed about 2 miles through three traffic lights. The GCIT entrance is on the left at the bottom of the hill. ROUTE 55 Exit at 56B (Route 47 Delsea Drive North) At the first light take a left (Bankbridge Road.) Follow Bankbridge to first traffic light and turn left (Tanyard Road). -

RI6 Some Observations on the Sediments of the Delaware River

Public Access Copy DO NOT REMOVE fro m room 208 . STATE OF DELAWARE DELAWARE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY REPORT OF INVESTIGATIONS NO.6 SOME OBSERVATIONS ON THE SEDIMENTS OF THE DELAWAR E RIVER SOUTH OF WILMINGTON By Robert R. Jordon and Johon J. Groot Newark, De laware February, 196 2 SOME OBSERVATIONS ON THE SEDIMENTS OF THE DELAWARE .RIVER SOUTH OF WILMINGTON By Robert R. lordan Geologist, Delaware Geological Survey and lohan I. Groot State Geologist February, 1962 CONTENTS P... Abstract ••• ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• '.e •••••••• • .1 Introduction. •••••• •• ................................ .1 Description of samples .........•..•.................... • •••••••••• 1 Megascopic descriptions •. .....•................................... 1 Microscopic descriptions ...........................................•1 Mechanical analyses •• ......................... , .. 4 Heavy mineral analyses . .................... • 4 Clay mineralogy. ................................. 6 Plant microfossils • ...................................... .6 Discussion ' 6 References. ......................... 12 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. Location of boring studied in this report ••••••••••••••••••••••••• •• 2 2. Log of boring showing location of samples •••••••••••••••••••••••••• 3 3. Cumulative curves of samples 20908· 20916 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• 5 4. Median grain size, heavy minerals and arborial pollen •••••••••••••••• •• 7 TABLES Table 1. Mechanical composition: statistical parameters. ••9 2. Percentages of heavy minerals 10 3. Percentages -

Disbursements of State-Administered Toll Road and Crossing Facilities - 1996 1

DISBURSEMENTS OF STATE-ADMINISTERED TOLL ROAD AND CROSSING FACILITIES - 1996 1/ TABLE SF-4B OCTOBER 1997 ( THOUSANDS OF DOLLARS ) SHEET 1 OF 2 BALANCES END OF YEAR ADMINIS TRATION HIGHWAY TOTAL RESERVES RESERVES STATE NAME OF FACILITY CAPITAL MAINTENANCE OPERATIONS AND LAW INTEREST BOND TRANSFERS DISBURSEMENTS FOR FOR OUTLAY MISCEL- ENFORCE- RETIREMENT 2/ CONSTRUCTION, DEBT LANEOUS MENT OPERATION, ETC. SERVICE Alaska Alaska Ferry (Marine Highway) System 30,667 2,400 62,550 3,740 - 78 1,236 - 100,671 - - California Mid-State Toll Road, State Routes 125, 91, & 57 3/ 837 - - - - - - - 837 - - Northern San Francisco Bay Bridges 4/ 24,986 4,016 9,251 4,785 - 1,266 2,360 767 47,431 289,692 4,962 San Diego-Coronado Bridge 5,043 1,726 1,440 654 - - - 3,441 12,304 8,748 - Southern San Francisco Bay Bridges 5/ 53,352 11,672 11,216 6,458 - 1,144 3,810 22,477 110,129 257,756 6,958 Vincent Thomas Bridge 3,110 748 1,249 - - - - - 5,107 11,802 - Total 87,328 18,162 23,156 11,897 - 2,410 6,170 26,685 175,808 567,998 11,920 Connecticut Rockyhill-Glastonbury and Chester-Hadlyme Ferries - - 387 - - - - - 387 - - Delaware Delaware Memorial Bridge and Cape May-Lewes Ferry 27,085 - 26,690 8,788 3,709 7,730 4,520 - 78,522 109,272 11,745 John F. Kennedy Memorial Highway and SR-1 Toll Road 47,733 5,987 2,149 1,416 - - - - 57,285 4,422 - Total 74,818 5,987 28,839 10,204 3,709 7,730 4,520 - 135,807 113,694 11,745 Florida Buccaneer Trail Road - 1,391 342 - - - - - 1,733 - - Central Florida Expressway - 120 753 - - - - 937 1,810 - - Everglades Parkway - 115 1,520 -

Observations of Tidal Flow in the Delaware River

Observations of Tidal Flow in the Delaware River GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1586-C Prepared in cooperation with the Corps of Engineers, Department of the Army, and the New Jersey Department of Conserva tion and Economic Development Observations of Tidal Flow in the Delaware River By E. G. MILLER HYDROLOGY OF TIDAL STREAMS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1586-C Prepared in cooperation with the Corps of Engineers, Department of the Army, and the New Jersey Department of Conserva tion and Economic Development TNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1962 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C. CONTENTS Page Abstract_____________________________ _________________________ Cl Introduction ______________________________________________________ 1 Purpose and scope.____________________________________________ 2 Acknowledgments.____________________________________________ 2 Collection of field data_____________________________________________ 3 Index current meter.__________________________________________ 3 Additional observations._______________________________________ 6 Soundings. ____________________________________________________ 6 Determination of mean velocity_________________________________ 6 Analyses of data_________________________________________________ 8 Velocity variations.-..-_-_-__--____________--__--__-_-___--_--_ 8 Gage-height variations-_-_-__-______-___-_____---___--___--_-__