2.0 Background Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allied Painting Secures Delaware Memorial Bridge Contracts

Project Preview Allied Painting Secures Delaware MemorialBy Alyssa Gallagher, Paint Bridge BidTracker Contracts he Delaware River Gulf War. Allied secured a and Bay Authority contract of $951,800 to recoat T awarded two con- 603,000 square feet of steel on tracts with a combined value the First Structure of $2,853,600 to Allied (Northbound) and a contract Painting, Inc. (Franklinville, of $1,901,800 to recoat NJ), SSPC-QP 1 and QP 2 cer- 659,500 square feet of steel on tified, to clean and recoat steel the Second Structure surfaces on the west girder (Southbound). The steel, spans of the Delaware including the interior of piers, Memorial Bridge. The 10,765- platforms, and ladders, will be foot-long twin spans connect Photo courtesy of Delaware River and Bay Authority spot power-tool cleaned New Castle, DE, and Pennsville, NJ, over the Delaware River. (SSPC-SP 3), spot-primed, and coated with a 4-coat moisture- The bridge is dedicated to veterans who gave their lives in cured urethane system. The contractor will employ a third- World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the party coatings inspector as part of the quality control plan. Click our Reader e-Card at paintsquare.com/ric www.paintsquare.com 70 JPCL July 2010 Crosno Construction to Rehabilitate Three Tanks Crosno Construction Inc. (San Luis Obispo, CA) secured a 100%-solids elastomeric polyurethane system. The project contract of $569,501.04 with the City of Sunnyvale, CA, to also includes the application of an epoxy-polyurethane sys- repair and reline three 60-foot-diameter by 24-foot-high steel tem to exterior surfaces. -

The Mill Creek Hundred History Blog: the Greenbank Mill and the Philips

0 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In The Mill Creek Hundred History Blog Celebrating The History and Historical Sites of Mill Creek Hundred, in the Heart Of New Castle County, Delaware Home Index of Topics Map of Historic Sites Cemetery Pictures MCH History Forum Nostalgia Forum About Wednesday, February 20, 2013 The Greenbank Mill and the Philips House -- Part 1 The power of the many streams and creeks of Mill Creek Hundred has been harnessed for almost 340 years now, as the water flows from the Piedmont down to the sea. There have been literally dozens of sites throughout the hundred where waterwheels once turned, but today only one Greenbank Mill in the 1960's, before the fire Mill Creek Hundred 1868 remains. Nestled on the west bank of Red Clay Creek, the Search This Blog Greenbank Mill stands as a living testament to the nearly three and a half century tradition of water-powered milling in MCH. The millseat at Search Greenbank is special to the story of MCH for several reasons -- it was one of the first harnessed here, it's the longest-serving, and it's the only one still in operable condition. The fact that it now serves as a teaching tool Show Your Appreciation for the MCHHB With PDFmyURL anyone can convert entire websites to PDF! only makes it more special, at least in my eyes. The early history of the millseat at Greenbank is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside....Ok, it's not quite that bad, but the actual facts are far Recent Comments from clear. -

Federal Register/Vol. 70, No. 22/Thursday, February 3

5720 Federal Register / Vol. 70, No. 22 / Thursday, February 3, 2005 / Notices 1), Federal Aviation Administration, wish to receive confirmation that the FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Mr. 800 Independence Avenue, SW., FAA received your comments, include a Robert F. Kleinburd, Realty and Washington, DC 20591. self-addressed, stamped postcard. Environmental Program Manager, This notice is published pursuant to You may also submit comments Federal Highway Administration, 14 CFR 11.85 and 11.91. through the Internet to http:// Delaware Division, J. Allen Frear Issued in Washington, DC, on January 28, dms.dot.gov. You may review the public Federal Building, 300 South New Street, 2005. docket containing the petition, any Room 2101, Dover, DE 19904; Anthony F. Fazio, comments received, and any final Telephone: (302) 734–2966; or Mr. Mark Director, Office of Rulemaking. disposition in person in the Dockets Tudor, P.E., Project Manager, Delaware Office between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m., Department of Transportation, 800 Bay Petition for Exemption Monday through Friday, except Federal Road, P.O. Box 778, Dover, DE 19903; Docket No.: FAA–2005–20139. holidays. The Dockets Office (telephone Telephone (302) 760–2275. DelDOT Petitioner: Airbus. 1–800–647–5527) is on the plaza level Public Relations Office (800) 652–5600 Section of 14 CFR Affected: 14 CFR of the NASSIF Building at the (in DE only). 25.841(a)(2)(i) and (ii) and (3). Department of Transportation at the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The Description of Relief Sought: To above address. Also, you may review Federal Highway Administration permit certification of the Airbus Model public dockets on the Internet at (FHWA), in cooperation with the A380 airplane without meeting http://dms.dot.gov. -

Watershed Action Plan

Watershed Action Plan December 2002 Mission Watersheds Statement To protect, sustain, and enhance the quality and quantity of all water resources to insure the health, safety, and welfare of the citizens, and preserve the diverse natural resources and aesthetic and recreational assets of Chester County and its watersheds. Disclaimer The maps, data and information presented herein were compiled by the Chester County Water Resources Authority for the County of Chester, PA and are hereby referenced to the Chester County, Pennsylvania Water Resources Compendium (2001). These information and data are pro- vided for reference and planning purposes only. This document is based on and presents the best information available at the time of the preparation. Funding Partners Chester County and the Chester County Water Resources Authority express their appreciation to those entities who provided financial support for this effort. This project was funded by: • Chester County Board of Commissioners. • Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Recreation and Conservation, Keystone Recreation, Park and Conservation Fund Program. • Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, and U. S. Environmental Protection Agency Nonpoint Source Pollution Management Program. • Brandywine Valley Association and William Penn Foundation. • U. S. Geological Survey. Chester County Board of Commissioners Karen L. Martynick, Chairman Colin A. Hanna Andrew E. Dinniman Watershed Action Plan December 2002 Prepared by: Chester County Water Resources Authority Chester County Planning Commission Camp Dresser and McKee Gaadt Perspectives, LLC Prepared as a component of: Chester County, Pennsylvania Water Resources Compendium _________________________ Prepared under a Nonpoint Source Pollution Management Grant funded by Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection and U. -

6 CULTURAL HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Environmental Setting the Study Area, Located in New Castle County, Falls Within the Piedmont U

CULTURAL HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Environmental Setting The study area, located in New Castle County, falls within the Piedmont Uplands physiographic province, extending from just northwest of the Fall Line marking the transition from the Piedmont to the Coastal Plain and continuing west through the Piedmont. The following summary of the environmental setting of the Piedmont has been abstracted from Custer (1984). The Piedmont Uplands of Delaware represent the northern portion of the Delmarva Peninsula and are characterized by a generally high relief topography dissected by the narrow and sometimes steep stream valleys of relatively small drainage systems; isolated knolls rise above the general level of the landscape. Elevations in the study area range from 90 feet to 370 feet above mean sea level. Thornbury (1965) notes that, within the Piedmont Uplands, there are no large tributaries of the older incised river systems of the Susquehanna and the Delaware Rivers, and that the drainage systems tend to be of lower order. Although broad floodplains may be found along the higher order streams of White Clay Creek and the Brandywine, Elk and Northeast Rivers, the floodplains along the larger tributaries flowing through this portion of the region – the low order tributaries of these rivers - tend to be rather limited in size. The underlying geologic formations consist of folded Paleozoic and Pre-Cambrian metamorphic and igneous rocks. Soils are generally well-drained, but some poorly-drained areas occur in the floodplains and upland flats. The study area is crossed by seven drainages: Hyde Run and its tributary, Coffee Run, flow near the western end of the project area and are low order tributaries of Red Clay Creek; Red Clay Creek and two of its small unnamed tributaries run through the central portion; and Little Mill Creek and one of its tributaries, Little Falls Creek, flow near the eastern end of the project area (Figure 3 shows the locations of these streams). -

Action for Red Clay Creek (ARCC) a Comprehensive Watershed Management Plan

Action for Red Clay Creek (ARCC) A Comprehensive Watershed Management Plan Alyssa Baker Cate Blachly Erica Rossetti Megan Safranek 2017 Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 List of Figures 1 List of Tables 1 Mission Statement 2 Background 2 History 4 Problems 5 Goals 6 Existing Regulations/Ordinances 8 Management Strategies 9 Conclusions & Recommendations 12 Works Cited 14 List of Figures Figure 1: Christina Basin 2 Figure 2: 2001 Land use in the Delaware portion of the Red Clay Creek watershed 3 Figure 3: Red Clay Creek Watershed Location and Delineation 3 Figure 4: Riparian Buffer Opportunities in Red Clay Creek, Delaware 10 List of Tables Table 1: Description and Causes of Problems 5 Table 2: Nutrient Concentration and Trends 6 Table 3: Winter Cover Crop Program in New Castle County, DE 11 Table 4: Possible % Financial Contributions of Red Clay Creek Municipalities 13 Table 5: Tentative Schedule 13 1 Mission Statement The goals of the Action for Red Clay Creek plan (ARCC) are: to attain the acceptable levels of TMDLs, to improve water quality such that each water body is removed from the EPA 303d list of impaired streams, and to reduce flooding in the Red Clay Creek watershed by the year 2030. Background Red Clay Creek is a 54 square mile watershed that is part of the Christina River Basin (Figure 1), which is a subbasin of the Delaware River Basin. It is split between southern Chester County (PA) and northern New Castle County (DE) and is a large source of drinking water for these areas via streams and wells. -

It's the Way to Go at the Peace Bridge

The coupon is not an invoice. If you Step 3 Read the customer guide New Jersey Highway Authority Garden State Parkway are a credit card customer, you don’t carefully. It explains how to use E-ZPass have to worry about an interruption and everything else that you should know New Jersey Turnpike Authority New Jersey Turnpike in your E-ZPass service because we about your account. Mount your tag and New York State Bridge Authority make it easy for you by automatically you’re on your way! Rip Van Winkle Bridge replenishing your account when it hits Kingston-Rhinecliff Bridge a low threshold level. Mid-Hudson Bridge Newburgh-Beacon Bridge For current E-ZPass customers: Where it is available. Bear Mountain Bridge If you already have an E-ZPass tag from E-ZPass is accepted anywhere there is an E-ZPass logo. New York State Thruway Authority It’s the Way another toll agency such as the NYS This network of roads aids in making it a truly Entire New York State Thruway including: seamless, regional transportation solution. With one New Rochelle Barrier Thruway, you may use your tag at the account, E-ZPass customers may use all toll facilities Yonkers Barrier Peace Bridge in an E-ZPass lane. Any where E-ZPass is accepted. Tappan Zee Bridge to Go at the NYS Thruway questions regarding use of Note: Motorists with existing E-ZPass accounts do not Spring Valley (commercial vehicle only) have to open a new or separate account for use in Harriman Barrier your tag must be directed to the NYS different states. -

EM Directions.Ai

TO: COMPANY: FAX: FROM: 100 Melrose Ave., Cherry Hill, NJ 08003 Driving Directions tel (800) 223-1376 fax (856) 428-5477 FROM NEW JERSEY: From Northern NJ: From Southern NJ: Take I-295 South to Exit #31 for Woodcrest Station. Take I-295 North to Exit #31 for Woodcrest Station. At the end of the exit ramp, turn left at the traffic light. At the end of the exit ramp, turn left at the traffic light. Our building is immediately on the left (about 100 yards). Our building is immediately on the left (about 100 yards). FROM PENNSYLVANIA: From Ben Franklin Bridge: From Walt Whitman Bridge: Cross the Ben Franklin Bridge into New Jersey. Cross the Walt Whitman Bridge into New Jersey. Take Rt. 676 East until you reach Route 42. Take Route 42 South until you reach I-295 North. Take Rt. 42 South until you reach I-295 North. Take I-295 North to Exit #31 for Woodcrest Station. Take I-295 North to Exit #31 for Woodcrest Station. At the end of the exit ramp, turn left at the traffic light. At the end of the exit ramp, turn left at the traffic light. Our building is immediately on the left (about 100 yards). Our building is immediately on the left (about 100 yards). FROM DELAWARE: Cross the Delaware Memorial Bridge into New Jersey. Take I-295 North to Exit #31 for Woodcrest Station. At the end of the exit ramp, turn left at the traffic light. Our building is immediately on the left (about 100 yards). -

New Castle County

State of Delaware Department of Transportation Capital Transportation Program FY 2011 – FY 2016 New Castle County NewStatewide Castle - GrantsCounty & Allocations - Grants & Allocations 204 State of Delaware Department of Transportation Capital Transportation Program FY 2011 – FY 2016 Road Systems New Castle County - Road Systems 205 State of Delaware Department of Transportation Capital Transportation Program FY 2011 – FY 2016 Expressways New Castle County - Road Systems - Expressways 206 State of Delaware Department of Transportation Capital Transportation Program FY 2011 – FY 2016 Project Title Primavera # Project # Glenville Subdivision Improvements 09-00122 T200904401 Project This project involves the reconstruction of the remaining streets and sidewalks in the Glenville Subdivision as a result of DelDOTs Glenville Wetland Bank Project. The project will Description provide a connector road between Harbeson and East Netherfield. Project This project is a continuation of the Glenville Wetland Banking project that will restore the remaining subdivison streets and reconnect the Glenville Subdivision Justification Funding Program ROAD SYSTEMS EXPRESSWAYS Senatorial District(s) 9 Representative District(s) 19 New Castle County - Road Systems - Expressways 207 State of Delaware Department of Transportation Capital Transportation Program FY 2011 – FY 2016 Glenville Subdivision Improvements PROJECT AUTHORIZATION SCHEDULE IN ($000) FY 2011 FY 2012 FY 2013 FY 2014 PROJECT CURRENT STATE FEDERAL PHASE FUNDING SOURCE NUMBER ESTIMATE TOTAL TOTAL -

Re-Introduction of Freshwater Mussels Into Red Clay And

PARTNERSHIP Re-Introduction of Freshwater FOR THE Mussels into Red Clay and White DELAWARE ESTUARY Clay Creeks, DE Final report for White Clay Wild and Scenic & Interim Report for Delaware Clean Water Advisory Council A publication of the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary; A National Estuary Program February, 2014 PDE Report No. 14-02 Authors Danielle Kreeger, Ph.D., Kurt Cheng, Priscilla Cole, Angela Padeletti Acknowledgements This work was made possible through funding from the Clean Water Advisory Council of the State of Delaware and the White Clay Wild and Scenic Program. We are grateful to Doug Janiec and Joshua Moody for assisting in surveying mussels at Thompson’s Bridge in November 2012. Gus Wolfe, Elizabeth Horsey, Karen Forst, Lisa Wool and Dee Ross assisted in mussel tagging prior to relocation. Lee Ann Haaf and Jessie Bucker assisted in surveying mussels in White and Red Clay Creeks as well as monitoring surveys following relocation. Recommended citation for this material: Kreeger, D.A., K. Cheng, P. Cole and A. Padeletti. 2014. Partnership for the Delaware Estuary. 2014. Reintroduction of Freshwater Mussels into the Red and White Clay Creeks, DE. PDE Report No.14-02 Established in 1996, the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary is a non-profit organization based in Wilmington, Delaware. The Partnership manages the Delaware Estuary Program, one of 28 estuaries recognized by the U.S. Congress for its national significance under the Clean Water Act. PDE is the only tri-state, multi-agency National Estuary Program in the country. In collaboration with a broad spectrum of governmental agencies, non-profit corporations, businesses, and citizens, the Partnership works to implement the Delaware Estuary’s Table of Contents Authors ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Receipts of State-Administered Toll

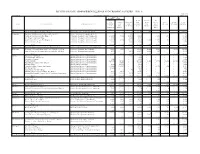

RECEIPTS OF STATE-ADMINISTERED TOLL ROAD AND CROSSING FACILITIES - 1996 1/ TABLE SF-3B OCTOBER 1997 ( THOUSANDS OF DOLLARS ) SHEET 1 OF 2 BALANCES BEGINNING OF YEAR 2/ RESERVES ROAD CONCES- NET FOR RESERVES HIGHWAY- AND SIONS INCOME MISCEL- BOND TOTAL STATE NAME OF FACILITY OPERATING AUTHORITY CONSTRUC- FOR USER CROSSING AND FROM LANEOUS PROCEEDS RECEIPTS TION, DEBT REVENUES TOLLS RENTALS INVEST- OPERATION, SERVICE MENTS ETC. Alaska Alaska Ferry (Marine Highway) System Alaska Department of Public Works - - - 15,200 7,800 - 77,671 - 100,671 California Mid-State Toll Road, State Routes 125, 91, & 57 Private Operators (California DOT) 3/ - - 837 - - - - - 837 Northern San Francisco Bay Bridges 4/ California Transportation Commission 242,000 4,962 23,680 56,256 - 14,951 237 - 95,124 San Diego-Coronado Bridge California Transportation Commission 10,564 - 3,889 6,024 - 572 4 - 10,489 Southern San Francisco Bay Bridges 5/ California Transportation Commission 250,523 6,958 26,413 72,670 3,100 14,893 285 - 117,361 Vincent Thomas Bridge California Transportation Commission 10,467 - 3,169 2,650 - 621 1 - 6,441 Total 513,554 11,920 57,988 137,600 3,100 31,037 527 - 230,252 Connecticut Rockyhill-Glastonbury and Chester-Hadlyme Ferries Connecticut Department of Transportation - - 186 201 - - - - 387 Delaware Delaware Memorial Bridge and Cape May-Lewes Ferry Delaware River and Bay Authority 62,427 8,848 - 53,725 4,004 4,843 387 65,305 128,264 John F. Kennedy Memorial Highway and SR-1 Toll Road Delaware Transportation Authority 4,938 - 6,075 48,337 2,068 -

North Atlantic Ocean

210 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 6 26 SEP 2021 75°W 74°30'W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 3—Chapter 6 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml Trenton 75°30'W 12314 P ENNSYLV ANIA Philadelphia 40°N 12313 Camden E R I V R E R Wilmington A W A L E D NEW JERSEY 12312 SALEM RIVER CHESAPEAKE & DELAWARE CANAL 39°30'N 12304 12311 Atlantic City MAURICE RIVER DELAWARE BAY 39°N 12214 CAPE MAY INLET DELAWARE 12216 Lewes Cape Henlopen NORTH ATL ANTIC OCEAN INDIAN RIVER INLET 38°30'N 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 6 ¢ 211 Delaware Bay (1) This chapter describes Delaware Bay and River and (10) Mileages shown in this chapter, such as Mile 0.9E their navigable tributaries and includes an explanation of and Mile 12W, are the nautical miles above the Delaware the Traffic Separation Scheme at the entrance to the bay. Capes (or “the Capes”), referring to a line from Cape May Major ports covered are Wilmington, Chester, Light to the tip of Cape Henlopen. The letters N, S, E, or Philadelphia, Camden and Trenton, with major facilities W, following the numbers, denote by compass points the at Delaware City, Deepwater Point and Marcus Hook. side of the river where each feature is located. Also described are Christina River, Salem River, and (11) The approaches to Delaware Bay have few off-lying Schuylkill River, the principal tributaries of Delaware dangers. River and other minor waterways, including Mispillion, (12) The 100-fathom curve is 50 to 75 miles off Delaware Maurice and Cohansey Rivers.