Effectiveness of Transit Operations in Texas Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobility Payment Integration: State-Of-The-Practice Scan

Mobility Payment Integration: State-of-the-Practice Scan OCTOBER 2019 FTA Report No. 0143 Federal Transit Administration PREPARED BY Ingrid Bartinique and Joshua Hassol Volpe National Transportation Systems Center COVER PHOTO Courtesy of Edwin Adilson Rodriguez, Federal Transit Administration DISCLAIMER This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. Mobility Payment Integration: State-of-the- Practice Scan OCTOBER 2019 FTA Report No. 0143 PREPARED BY Ingrid Bartinique and Joshua Hassol Volpe National Transportation Systems Center 55 Broadway, Kendall Square Cambridge, MA 02142 SPONSORED BY Federal Transit Administration Office of Research, Demonstration and Innovation U.S. Department of Transportation 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20590 AVAILABLE ONLINE https://www.transit.dot.gov/about/research-innovation FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION i FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION i Metric Conversion Table SYMBOL WHEN YOU KNOW MULTIPLY BY TO FIND SYMBOL LENGTH in inches 25.4 millimeters mm ft feet 0.305 meters m yd yards 0.914 meters m mi miles 1.61 kilometers km VOLUME fl oz fluid ounces 29.57 milliliters mL gal gallons 3.785 liter L ft3 cubic feet 0.028 cubic meters m3 yd3 cubic yards 0.765 cubic meters m3 NOTE: volumes greater than 1000 L shall be shown in m3 MASS oz ounces 28.35 grams g lb pounds 0.454 kilograms kg megagrams T short tons (2000 lb) 0.907 Mg (or “t”) (or “metric ton”) TEMPERATURE (exact degrees) o 5 (F-32)/9 o F Fahrenheit Celsius C or (F-32)/1.8 FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION i FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION ii REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. -

CSCIP Module 5 - Payments and Financial Transactions Final - Version 3 - October 8, 2010 1 for CSCIP Applicant Use Only

Module 5: Smart Card Usage Models – Payments and Financial Transactions Smart Card Alliance Certified Smart Card Industry Professional Accreditation Program Smart Card Alliance © 2010 CSCIP Module 5 - Payments and Financial Transactions Final - Version 3 - October 8, 2010 1 For CSCIP Applicant Use Only About the Smart Card Alliance The Smart Card Alliance is a not-for-profit, multi-industry association working to stimulate the understanding, adoption, use and widespread application of smart card technology. Through specific projects such as education programs, market research, advocacy, industry relations and open forums, the Alliance keeps its members connected to industry leaders and innovative thought. The Alliance is the single industry voice for smart cards, leading industry discussion on the impact and value of smart cards in the U.S. and Latin America. For more information please visit http://www.smartcardalliance.org . Important note: The CSCIP training modules are only available to LEAP members who have applied and paid for CSCIP certification. The modules are for CSCIP applicants ONLY for use in preparing for the CSCIP exam. These documents may be downloaded and printed by the CSCIP applicant. Further reproduction or distribution of these modules in any form is forbidden. Copyright © 2010 Smart Card Alliance, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction or distribution of this publication in any form is forbidden without prior permission from the Smart Card Alliance. The Smart Card Alliance has used best efforts to ensure, but cannot guarantee, that the information described in this report is accurate as of the publication date. The Smart Card Alliance disclaims all warranties as to the accuracy, completeness or adequacy of information in this report. -

Final Table of Contents.Pub

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority 2010 congestion management program Board of Directors Don Knabe Board Chairman Los Angeles County Supervisor Fourth Supervisorial District Antonio R. Villaraigosa 1st Vice Chair Mayor, City of Los Angeles Michael D. Antonovich 2nd Vice Chair Los Angeles County Supervisor Fifth Supervisorial District Diane DuBois City Council Member, Lakewood John Fasana City Council Member, Duarte José Huizar City Council Member, Los Angeles Richard Katz City of Los Angeles Gloria Molina Los Angeles County Supervisor First Supervisorial District Ara Najarian Mayor, City of Glendale Pam O’Connor City Council Member, Santa Monica Mark Ridley-Thomas Los Angeles County Supervisor Second Supervisorial District Rita Robinson City of Los Angeles Zev Yaroslavsky Los Angeles County Supervisor Third Supervisorial District Los Angeles County Prepared by: Long Range Planning Metropolitan Transportation Authority and Coordination One Gateway Plaza Los Angeles, CA 90012-2952 213.922.6000 metro.net 2010 Congestion Management Program Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority Arthur T. Leahy, Chief Executive Officer Martha Welborne, Executive Director, Countywide Planning Bradford W. McAllester, Executive Officer, Long Range Planning and Coordination Congestion Management Program Staff: Heather Hills, Director, Long Range Planning Stacy Alameida, Transportation Planning Manager/CMP Program Manager Scott Hartwell, Transportation Planner Doreen Morrissey, Transportation Planner TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter -

Fare Box and Public Revenue

FARE BOX AND PUBLIC REVENUE: HOW TO FINANCE PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION Cooperative Research Technical Report 1057-lF Study No. 2-10-79-1057 Sponsored by the STATE DEPARTMENT OF HIGHWAYS AND PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION In Cooperation With U.S. Department of Transportation Urban Mass Transportation Administration TEXAS TRANSPORTATION INSTITUTE TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY COLLEGE STAT ION, TEXAS TECHNICAL REPORT STANDARD TITLE ?ACE 1. Report No. 2. Co..,ernment Acce111on No. 3. Recipient' I Cotolog No. UMTATX 79-10571 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Dote Fare Box and Public Revenue: How to Finance February 1980 Public Transportation 6. Performing Orgoni zotion Code 7. Author's) 8. Performing Organi zotion Report No. Randall S. Billingsley, Patricia K. ~useman, and William F. McFarland Technical Report 1057-lF 9. Performing Organization Nome and Address 10. Work Unit No. Texas Transportation Institute Texas A&M University 1 J. Contract or Grant' No. College Station, Texas 77843 Study No. 2-10-78-1057 13. Type of Report and P&<"iod Covered ~~~~~~~~~~~~~-- 12. Sponsoring Agency Nome and Address State Department of Highways and Public Transportation Final Report Transportation Planning Division February 1978-April 1979 P.O. Box 5051 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Austin, Texas 78763 15. Supplementary Notes This study was conducted in cooperat~on with the Urban Mass Transportation Administration 16. Abstract To be effective, governmental funds for public transit services must be based on sound approaches for providing and distributing subsidies. This report provides a review of the impacts of current capital and operating grants programs. Recommendations are made for a combination of provider side subsidies and user-side subsidies. -

NRTA Year Round Bus Service Study-Phase 2

,.. _, i ’f“l* I _:: : P,,_, /___ ____":% iiiiiiit ' <-‘Q ;\~__\\"‘,v'-"* -1‘ é 7 _ -' 2:-.*:! _____ _ iii, L ' _2' _ -—- *“§l E ?:7 55,- _ ,_ L L k ¢_ '___._,.i,;,, 1 _;,_; 1 II ‘ Photo by Susan Richards, SR Concepts 94% 1; K / W1 ' u<'§ -7." Q 1!“ '2 '~ ~ W, " \, 1/1 / ‘-\é‘ i 1 ‘ V J if -=) ‘ __ .-. 1; _" _. ‘ ' , ,_ rs. V\_ ‘ \ . \' " £2~.@in _ , H: I ... I 7“ - K ‘ - 5' ‘ <’ _ {ii} __.4;..* ~22” ‘TiIt K ' I \.1\>\ i? gii -Photo by Susan Richards, SR Concepts I . - Photo by SusanK‘ Richards," SR Concepts Photo by Susan Richards, SR Concepts 4 Q , § =\__§__ \ V ‘ I-1‘ 1 llflllilifilfil HODIOMI U888“fllllflfifill NRTA Year-Round Bus Service Study Phase II Report: Fare Policy Review and Development of Innovative Funding Options Nantucket Regional Transit Authority December 2016 NRTA Year-Round Bus Service Study Phase II Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ ES-1 Local Outreach ................................................................................................................... ES-1 Innovative Funding Options ................................................................................................ ES-1 Fare Policy Analysis ............................................................................................................. ES-2 Fare Collection Technology Analysis.................................................................................... ES-2 Next Steps ......................................................................................................................... -

Best Practices – Customer Messaging for Transit Open Payments

Best Practices – Customer Messaging for Transit Open Payments October 2020 1 Overview • Objective of this presentation: Document consumer communication best practices on availability of contactless bank card (physical & virtual) acceptance in transit at points of entry for accessing modes of transportation • Topics discussed: – Transit agency communication planning and engagements at different project phases – Communications examples from transit agencies, payment networks, mobile wallets • Note: Contactless bank card acceptance at points of entry is commonly referred to as open payments in transit. 2 Communications by Implementation Phases Phase 1: Initiation Phase 2: Development Quiet Position stated but not promoted Quiet Phase 3: Implementation (Pilot/Soft Launch) Engaging with regional Position stated but not issuers, digital wallets promoted Phase 4: Rollout providers & major brands Occasional marketing on planned launch Defining multiyear marketing agreement Active future positioning Phase 5: In framework with primary Occasional marketing Market/Ongoing issuers, digital wallet providers, and card brands Active future positioning Sustained promotion Active future positioning Sustained promotion 3 Communications by Media Channel Phase 3: Implementation (Pilot/Soft Phase 4: Rollout Phase 5: In Market/Ongoing Launch) • In Station • In Station • In Station • Permanent signage • Permanent signage • Permanent signage • Advertising • Advertising • Advertising • Signage on vending machines • Signage on vending machines • Signage on vending -

“Impact of Common Mobility Card on Travel Pattern

“IMPACT OF COMMON MOBILITY CARD ON TRAVEL PATTERN” CASE STUDY –DELHI #mobility as a service #ease the mobility Anshula Gumber School of Planning and Architecture, Delhi UP METRO Need of the Study Different Modes Different Fare Structures Hassle free and seamless travel Modern Technologies provide modern solutions • Facilitates multi-modal travel behavior. Commuters • Commuters just have to carry one card • Encourages faster boarding • Hassle free transaction. Enables commuters to enjoy the benefits of integrated fare policies. • Collection of real time data Transport Authorities • Complex fare schemes. • Help operators to balance peak • Expandable to the other and off peak patronage. services like toll payment, • Faster reconciliation of revenue congestion pricing in CBD with recorded data. areas, and parking and further for retail shopping. • It saves manhandling hours • Elimination of fake currency • Increases the accountability and from the economy. transparency of the transactions. • Increase the accessibility. • Enables the authorities to maintain the extra sum of money Literature Review London -Oyster Number Populati Cards/1000 Technology Additional SchemeAtlanta - MARTA Breeze Card TFL OysterTransport DublinCardmodes LUAS + NationalFunctions ITS of cards on served head used %of depositinformation to Boston - MBTACity Charlie Card Deposit MaximumToulouse- Pastel Fare TFLChicago Oyster - CTA43 Parameter Ventra8.17 5,263 Contactless Bus, Tube,Before Tram, LondonParis Docklands- Navigo Transit, RetailsAftermaximum and Concession fare -

APPENDIX G 2018 Regional Transportation Plan Coordinated Transportation Plan for Seniors and People with Disabilities

APPENDIX G 2018 Regional Transportation Plan Coordinated transportation plan for seniors and people with disabilities December 6, 2018 oregonmetro.gov/rtp Metro respects civil rights Metro fully complies with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that requires that no person be excluded from the participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be otherwise subjected to discrimination on the basis of race, color or national origin under any program or activity for which Metro receives federal financial assistance. Metro fully complies with Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act that requires that no otherwise qualified individual with a disability be excluded from the participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination solely by reason of their disability under any program or activity for which Metro receives federal financial assistance. If any person believes they have been discriminated against regarding the receipt of benefits or services because of race, color, national origin, sex, age or disability, they have the right to file a complaint with Metro. For information on Metro’s civil rights program, or to obtain a discrimination complaint form, visit oregonmetro.gov/civilrights or call 503-797-1536. Metro provides services or accommodations upon request to persons with disabilities and people who need an interpreter at public meetings. If you need a sign language interpreter, communication aid or language assistance, call 503-797-1700 or TDD/TTY 503-797-1804 (8 a.m. to 5 p.m. weekdays) 5 business days before the meeting. -

Transportation Information and FAQ's

Transportation Information and FAQ’s How do I get the Metro Q Card with student discount? To get your student discount card, you have to go to the Metro Ridestore(1900 Main St.), close to the Downtown Transit Center. You will need to bring three documents with you: 1. A print out of your Class Schedule showing full time class status. (12hrs for UG, 9hrs for G and can be found at my.uh.edu) 2. A receipt or document showing fees paid for semester classes. 3. Your passport You have to add $5 to the Q Card when you go and pick it up. After you get the card(which can ONLY be issued at the Metro Ridestore(though, to renew the card, you can do so at the UH Welcome Center). You can charge your card in many other places, such as in the UH Welcome Center on campus, on the metro buses themselves, or at the Metro transit stations. How much does it cost to use the buses and Metrorail? It is currently $1.25 to use the buses and metrorail one-way in Houston, though the service is reduced by 50% if you apply online at ridemetro.org and register with a student discount(see above). What about the shuttle bus on campus, is it free? Yes, the shuttle service is free to use! You don’t even have to use your ID to get around in it, though this might not be the case in the future, keep that in mind when you use the shuttle buses. -

Oregon Department of Transportation Electronic Fare System Peer Analysis

Oregon Department of Transportation Electronic Fare System Peer Analysis December 19, 2016 Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................... 0 I. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 2 II. Implementation Cost ........................................................................................................................ 4 III. Funding Strategies ........................................................................................................................ 6 IV. Fare Policy Goals ........................................................................................................................... 8 V. Operations Impacts ........................................................................................................................... 9 VI. Public Outreach & Customer Adoption ...................................................................................... 10 VII. Staffing ........................................................................................................................................ 12 VIII. eFare Implementation Challenges .............................................................................................. 13 IX. Regional Inter-Agency Coordination ........................................................................................... 15 X. -

Houston-Galveston Regional Transit Services

Houston-Galveston Regional Transit Services SUMMARY Transit providers in the Houston-Galveston area demonstrate several examples of regional transit services that cross jurisdictional boundaries: • Harris County and METRO sponsor the Baytown Park & Ride to downtown Houston. • Connect Transit in Brazoria County is working with METRO to build and operate a park & ride from Pearland to the TMC (to open 2014). • Fort Bend County operates the Fort Bend Express to Uptown/Galleria, Greenway Plaza, and TMC. • Brazos Transit District operates The Woodland Express from Montgomery County to downtown Houston, Greenway Plaza, and the Texas Medical Center (TMC). FINDINGS Regional Overview The Area The Houston-Galveston metropolitan planning area includes eight counties and contains four urbanized areas as of Census 2010. The Houston urbanized area (UZA) is the largest, located mainly in Harris County. Table 1 provides the population and area of each County and UZA. Figure 1 provides a map of the urbanized areas as compared to the county boundaries. Table 1. Area Population and Size 2010 Area County 2000 Population 2010 Population (Sq.Miles) Brazoria County 241,767 313,166 1,386 Chambers County 26,031 35,096 599 Fort Bend County 354,452 585,375 875 Galveston County 250,158 291,309 398 Harris County 3,400,578 4,092,459 1,729 Liberty County 70,154 75,643 1,160 Waller County 32,663 43,205 514 Montgomery County 293,768 455,746 1,044 Total 4,566,754 5,891,999 7,705 Houston UZA 3,822,509 4,944,332 1,295 Conroe - The Woodlands UZA 89,445 239,938 42 Texas City UZA 96,417 106,383 59 Lake Jackson-Angleton UZA 73,416 74,830 34 Galveston UZA 54,770 N/A 12 Source: U.S. -

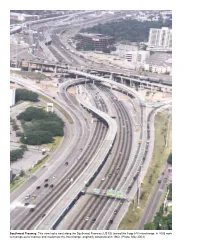

Southwest Freeway: This View Looks West Along the Southwest Freeway (US 59) Toward the Loop 610 Interchange

Southwest Freeway: This view looks west along the Southwest Freeway (US 59) toward the Loop 610 interchange. In 2003 work is in progress to improve and modernize the interchange, originally constructed in 1962. (Photo: May 2003) 381 ������������������������������ ��������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ��������������������� ������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������� ������� �� �� �������������������������������� �� �� ������������������������������������ �� �� �������������������������������� �� �� ���������� ���� �� �������������������������������������� �������� � � ������������������������������ ���� �� ���������������������������������� �� � �� ������������ ������ �� ����������������������������� � � � ������������������������ ������������ �� ������������������������������� � � � � � ����������������������������� � � ������������������������������������� ������� ������ � ���� ������� � ����� ��� ����� � � ������������ ���� � ������ � � � � ������� ������� � ���� �� ����� ���� ��������� � ���� ���� � ��� �������������������� �� � ������� ����� � ���� ������� � �� �� �� � ��� � ���� � ����� ����� ����� � �� ���� ���� ���� �� � � ���������� ���������� ����������� ����� � �� ��� � � � � � � � �� ����� ����� ����� �� �������� � � ���������� ���� � � ����������� ��� � � � � � �� ������� ���� � � �� �� �� ����� ���� ��� � � � ���� � � � � ���������������� �������������� � ������������� 382 Houston Freeways Downtown’s newest addition: The new Eastex Freeway downtown