Foreign Cuisine in Poland. Adapting Names and Dishes1 (This Article Was Translated from Polish by Jakub Wosik)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Śmierć W Lesie W Jednym Z Podgolubskich Lasów Znaleziono Mar- Twego 20-Latka

Dyżur reporterski tel. 721 093 072 Reklama w CGD tel. 608 688 587 [email protected] R E K L A M A M A R E K L A M A R E K L R E K L A M A M A R E K L tyment OFERUJÊ Golub-Dobrzyń Kowalewo Pomorskie PROMOCJA PELLET DRZEWNY na ca³y SKasor £AD WYSOKIEJ JAKOŒCI Powstała Dzień Matki WÊGLA DOSKONA£Y ZAMIENNIK ul. Szosa Rypiñska EKO-GROSZKU Młodzieżowa Rada u seniorów w naprzeciw szpitala (pakowany w 15kg worki) ATRAKCYJNE CENY Miasta Kowalewie SPRZEDA¯ RATALNA DOWÓZ GRATIS str. 3 str. 6 tel. 881 005 188 TEL. 606-148-049 ŚRODA 30 MAJA 2018 ISSN: 1899-864X 1,9 9 z ł w tym 5% VAT nr 22/2018 (500) 7<*2'1,.5(*,218*2/8%6.2'2%5=<ē6.,(*2 Klamka zapadła, „kowalewska” do remontu! POWIAT We wtorek 29 maja w Ostrowitem marszałek wo- jewództwa Piotr Całbecki podpisał umowę na przebudowę blisko dziesięciokilometrowego odcinka drogi z Kowalewa Pomorskiego do Golubia-Dobrzynia. Remont potrwa najdalej do końca roku JUBILEUSZ 500. numer CGD. Dziękujemy za zaufanie! Oddajemy właśnie w Państwa ręce pięćsetny numer Tygodnika Regionu Golubsko-Dobrzyńskiego CGD. Staramy się być wszędzie tam, gdzie dzieje się coś ciekawego. Dziękujemy, że od blisko dziesięciu lat jesteście z nami! Na zdjęciu, pierwsze wydanie naszego Tygodnika, z października 2008 roku. (ToB) Gmina Golub-Dobrzyń Śmierć w lesie W jednym z podgolubskich lasów znaleziono mar- twego 20-latka. Policja potwierdza, że mężczyzna po- – Przebudowa drogi po- bocza. Wykonana zostanie nowa czenia inwestycji to koniec tego pełnił samobójstwo. -

Katalog Produktów Marki PROSTE HISTORIE 2020

KATALOG PRODUKTÓW 2019/2020 ... to gotowanie z kilku składników połączonych w pyszne, domowe danie. ... to wiele produktów i smacznych pomysłów na wspaniały obiad. Prostymi Historiami dzielimy się codziennie przy wspólnym stole. Zupa zajmuje szczególne miejsce 1 zupa w polskiej kuchni, a my mamy na nią wiele pomysłów. Każdego dnia inspirujemy 2 drugie danie do gotowania pysznych domowych dań. 3 deser Podpowiadamy, jak przyrządzić proste i bardzo smaczne desery. 2 Składniki i wartości odżywcze Inspiracje kulinarne Sposób przygotowania Informacje facebook.com/niejempalmowego przyprawa w saszetce Przewagi i atrybuty produktu Gwarant jakości 3 Jak rozwijamy sprzedaż produktów Proste Historie? Silnie wspieramy naszą markę! Prowadzimy wysokobudżetowe kampanie reklamowe o zasięgu ogólnopolskim: TV, radio, internet, wsparcie PR. 52% Marki Proste Historie i Iglotex łącznie zna już 52% wszystkich Polaków! 20 mln Polaków Portfolio Proste Historie to TOPsellery oraz innowacje! Rozwijamy kategorie produktowe, wprowadzamy innowacyjne produkty na rynek. 4 Sprzedaż wartościowa marki Proste Historie (Cała Polska, dane półroczne) OOdnotowujemydnotowujemy sidużelne łącznie wwzrostyzrosty ssprzedaży!przedaży! +95% Od 2015 roku nasza sprzedaż Od 2015 roku nasza sprzedaż wwzrosłazrosła o prawie 65%! dwukrotnie! 1H2015 1H2016 1H2017 1H2018 1H2019 Mamy silną Pierogi, uszka - lider kategorii Mamypozycję sirynkową!lną Pyzy, kluski - lider kategorii pLiderozycję kategorii r ynkmącznej,ową! mączno-ziemniaczanejWa rzywa - wicelider kategorii i zapiekanek. Frytki - -

Urzędu Patentowego

Urząd Patentowy Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej BIULETYN Urzędu Patentowego Znaki towarowe Warszawa 2018 36 Urząd Patentowy RP – na podstawie art. 1461 ust. 1 i 3, art. 1526 ust. 1 i 2 oraz art. 2331 ustawy z dnia 30 czerwca 2000 r. Prawo własności przemysłowej (Dz. U. z 2013 r. poz. 1410 z późniejszymi zmianami) oraz rozporządzeń Prezesa Rady Ministrów wydanych na podstawie art. 152 powołanej ustawy – dokonuje ogłoszenia w „Biuletynie Urzędu Patentowego” o zgłoszonych znakach towarowych. W Biuletynie ogłasza się informacje o: zgłoszonych znakach towarowych, wyznaczonych na terytorium Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej międzynarodowych znakach towarowych, informację o sprzeciwach wniesionych wobec zgłoszenia znaku towarowego lub wyznaczonego na terytorium Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej międzynarodowego znaku towarowego. Ogłoszenia o zgłoszeniach znaków towarowych publikowane są w układzie numerowym i zawierają: – numer zgłoszenia, – datę zgłoszenia, – datę i kraj uprzedniego pierwszeństwa oraz numer zgłoszenia priorytetowego lub oznaczenie wystawy, – nazwisko i imię lub nazwę zgłaszającego oraz jego miejsce zamieszkania lub siedzibę i kraj (kod), – prezentację znaku towarowego, – klasy elementów obrazowych wg klasyfikacji wiedeńskiej, – wskazane przez zgłaszającego klasy towarowe oraz wykaz towarów i/lub usług. Ogłoszenia o wyznaczonych na terytorium Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej międzynarodowych znakach towarowych publikowane są w układzie numerowym i zawierają: – numer rejestracji międzynarodowego znaku towarowego, – określenie znaku towarowego, – datę -

Pacific Press® Publishing Association Nampa, Idaho Oshawa, Ontario, Canada Nancy Lyon Kyte

Pacific Press® Publishing Association Nampa, Idaho Oshawa, Ontario, Canada www.pacificpress.com NANCY LYON KYTE Vegetarian Soups and Stews From Around the World NANCY LYON KYTE Vegetarian Soups and Stews From Around the World Dedication Design by Gerald Lee Monks Cover design resources from iStockphoto.com / Dreamstime.com Inside design by Pacific Press® Publishing Association Copyright © 2012 by Pacific Press® Publishing Association Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved The author assumes full responsibility for the accuracy of all facts and quotations as cited in this book. Additional copies of this book are available by calling toll-free 1-800-765-6955 or by visiting http://www.adventistbookcenter.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kyte, Nancy Lyon, 1954- A taste of travel : vegetarian soups and stews from around the world / Nancy Lyon Kyte. pages cm ISBN 13: 978-0-8163-2871-0 (pbk.) ISBN 10: 0-8163-2871-4 (pbk.) 1. Vegetarian cooking. 2. International cooking. I. Title. TX837.K98 2012 641.59—dc23 2012023473 12 13 14 15 16 • 5 4 3 2 1 Dedication Dedicated to Bob, my husband, best friend, and trustworthy soup critic. I thank him with my whole heart. Acknowledgments Interior Photo Credits iStockphoto.com: 26–28, 31, 34–42, 44–51, 53–58, 60–66, 71–75,78, 80, 82, 84–86, 88–90, 92, 94, 96, 97–101, 103–108, 110–119, 121, 123, 125, 127–129, 131–134, 136, 138–142, 144, 145, 147–150, 152, 154, 159 Dreamstime.com: 30, 32, 33, 43, 59, 67–70, 76, 77, 79, 81, 87, 91, 93, 95, 120, 124, 126, 130, 135, 137, 143, 151, 153, 155–158 Global Mission: 52, 102 Acknowledgments I am so grateful to my sisters, Mary Hellman, Susan Rasmussen, and Sandra Child. -

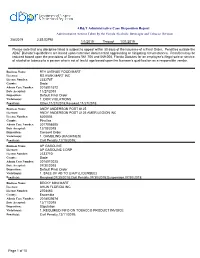

AB&T Administrative Case Disposition Report by Date

AB&T Administrative Case Disposition Report Administrative Actions Taken by the Florida Alcoholic Beverages and Tobacco Division 2/8/2019 2:35:52PM 1/1/2019 Through 1/31/2019 Please note that any discipline listed is subject to appeal within 30 days of the issuance of a Final Order. Penalties outside the AB&T Division's guildelines are based upon extensive documented aggravating or mitigating circumstances. Penalties may be reduced based upon the provisions of Sections 561.706 and 569.008, Florida Statutes for an employee's illegal sale or service of alcohol or tobacco to a person who is not of lawful age based upon the licensee's qualification as a responsible vendor. Business Name: 9TH AVENUE FOOD MART Licensee: RS KWIK MART INC License Number: 2332787 County: Dade Admin Case Number: 2018011572 Date Accepted: 11/27/2018 Disposition: Default Final Order Violation(s): 1. DOR VIOLATIONS Penalty(s): Other,11/27/2018;Revoked,11/27/2018; Business Name: ANDY ANDERSON POST #125 Licensee: ANDY ANDERSON POST #125 AMER LEGION INC License Number: 6200504 County: Pinellas Admin Case Number: 2017056505 Date Accepted: 12/18/2018 Disposition: Consent Order Violation(s): 1. GAMBLING (MACHINES) Penalty(s): Civil Penalty,12/18/2018; Business Name: AP GASOLINE Licensee: AP GASOLINE CORP License Number: 2333710 County: Dade Admin Case Number: 2018012025 Date Accepted: 07/30/2018 Disposition: Default Final Order Violation(s): 1. SALE OF AB TO U/A/P (LICENSEE) Penalty(s): Revoked,07/30/2018;Civil Penalty,07/30/2018;Suspension,07/30/2018; Business Name: BECKY MINI MART Licensee: AHUN FLORIDA INC License Number: 2704463 County: Escambia Admin Case Number: 2018039574 Date Accepted: 12/11/2018 Disposition: Stipulation Violation(s): 1. -

The Magic of Christmas at Intercontinental Warsaw

Celebrate The Magic of Christmas at InterContinental Warsaw WARSZAWA.INTERCONTINENTAL.COM | WYJATKOWECHWILE.COM.PL WARSZAWA.INTERCONTINENTAL.COM | WYJATKOWECHWILE.COM.PL | WARSZAWA.INTERCONTINENTAL.COM Our offer Christmas 2017 Menu – Served Menu .................................... 4-5 Christmas Buffet 1 .................................... 6-7 Christmas Buffet 1I .................................... 8-9 Christmas 2017 Special Buffet .................................... 10-11 Live Cooking Stations Christmas Offer .................................... 14-15 Christmas Beverage Packages 2017 .................................... 16-17 Additional entertainment offer .................................... 18-19 2+3 WARSZAWA.INTERCONTINENTAL.COM | WYJATKOWECHWILE.COM.PL | WARSZAWA.INTERCONTINENTAL.COM CHRISTMAS 2017 MENU – SERVED MENU Prices are VAT and 5% service fee exclusive. Menu 1 Menu 2 Menu 3 Menu 4 125 PLN net per person 125 PLN net per person 155 PLN net per person 155 PLN net per person Cream of mushroom soup with prunes Tuna tartare with sour cream and horseradish Smoked goose half breast with rosemary Salmon Gravlax marinated with peppercorns and sour cream sauce with wasabi jelly and caramelised shallots and brandy, served on beetroot carpaccio ggggggggggggggggggggg ggggggggggggggggggggg ggggggggggggggggggggg with nut foam Atlantic cod fillet in Polish grey sauce Roast pork tenderloin in mushroom sauce, Cream of pumpkin soup with cinnamon ggggggggggggggggggggg with almonds and raisins, served served with roast winter vegetables and -

Kąpieliska I Szynobusem

Str. 4 Str. 9 Str. 11-15 Aquapark Lato ww mieściemieście co będzie granegrane wielkie zmianyzmiany Twoja oazaoaza domdom ii ogród MIESIĘCZNIK BEZPŁATNY • NAKŁAD 13 000 EGZ. • 28 CZERWCA 2012 R. NR 9 (19)/2012 • ISSN 2083-8565 • Do kurortu po szynach Kolejny letni sezon z Koszałkiem Kąpieliska i szynobusem. Letnia komu- nikacja Koszalina z nadmor- skimi kurortami – Mielnem czekają na ciebie i Unieściem rusza na niemal identycznych zasadach, co Mieszkańcy regionu koszalińskiego Orła Białego oraz od ul. Słonecznej do Unieścia. w latach Strona 3 nie będą w tym roku narzekać na brak W Sarbinowie miejsca kąpielowe będą między ubiegłych. kąpielisk. Bezpiecznie zamoczyć będzie ul. Plażową a pętlą autobusową. W Łazach miej- się można aż w 13 miejscach nad morzem sca kąpielowe będą przy ul. Wczasowej oraz ul. i w trzech nad jeziorami. Leśnej. Po co to rozróżnienie? Obowiązujące od Nasze ubiegłego roku przepisy wprowadzają w Polsce drogie dzieci Kąpieliska nadmorskie powstaną w tym roku rozróżnienie na kąpieliska i miejsca przeznaczone Cztery dodatkowe oddziały w Mielnie, Unieściu, Łazach, Mielenku, Chłopach, do kąpieli. Dla korzystających z tych miejsc róż- przedszkolne będą utworzone Sarbinowie i Gąskach. Wszystkie czynne będą od nica w nazwie nie ma żadnego znaczenia. W naj- w Koszalinie, uczęszczać do nich 1 lipca do 31 sierpnia. Największe powstanie tra- większym skrócie różnice między tymi miejscami będzie 170 dzieci, których rodzice dycyjnie w Mielnie. Plaża strzeżona będzie miała polegają na tym, że w kąpieliskach sanepid sam złożyli odwołania, bo nie przyjęto długość pięciuset metrów i będzie pilnowana kontroluje jakość wody, a w miejscach kąpielo- ich pociech do przedszkoli. przez 15 ratowników jednorazowo. -

Soups & Stews Cookbook

SOUPS & STEWS COOKBOOK *RECIPE LIST ONLY* ©Food Fare https://deborahotoole.com/FoodFare/ Please Note: This free document includes only a listing of all recipes contained in the Soups & Stews Cookbook. SOUPS & STEWS COOKBOOK RECIPE LIST Food Fare COMPLETE RECIPE INDEX Aash Rechte (Iranian Winter Noodle Soup) Adas Bsbaanegh (Lebanese Lentil & Spinach Soup) Albondigas (Mexican Meatball Soup) Almond Soup Artichoke & Mussel Bisque Artichoke Soup Artsoppa (Swedish Yellow Pea Soup) Avgolemono (Greek Egg-Lemon Soup) Bapalo (Omani Fish Soup) Bean & Bacon Soup Bizar a'Shuwa (Omani Spice Mix for Shurba) Blabarssoppa (Swedish Blueberry Soup) Broccoli & Mushroom Chowder Butternut-Squash Soup Cawl (Welsh Soup) Cawl Bara Lawr (Welsh Laver Soup) Cawl Mamgu (Welsh Leek Soup) Chicken & Vegetable Pasta Soup Chicken Broth Chicken Soup Chicken Soup with Kreplach (Jewish Chicken Soup with Dumplings) Chorba bil Matisha (Algerian Tomato Soup) Chrzan (Polish Beef & Horseradish Soup) Clam Chowder with Toasted Oyster Crackers Coffee Soup (Basque Sopa Kafea) Corn Chowder Cream of Celery Soup Cream of Fiddlehead Soup (Canada) Cream of Tomato Soup Creamy Asparagus Soup Creamy Cauliflower Soup Czerwony Barszcz (Polish Beet Soup; Borsch) Dashi (Japanese Kelp Stock) Dumpling Mushroom Soup Fah-Fah (Soupe Djiboutienne) Fasolada (Greek Bean Soup) Fisk och Paprikasoppa (Swedish Fish & Bell Pepper Soup) Frijoles en Charra (Mexican Bean Soup) Garlic-Potato Soup (Vegetarian) Garlic Soup Gazpacho (Spanish Cold Tomato & Vegetable Soup) 2 SOUPS & STEWS COOKBOOK RECIPE LIST Food -

Lunch Breaks Menu Proposals

Smaki Miasta Catering al. Niepodległości 147, 02-555 Warszawa | tel. 515 125 263, [email protected] www.smaki-miasta.pl LUNCH BREAKS MENU PROPOSALS PROPOSAL 1 Main course: Chicken De Volaille Sole in lime sauce Pancakes with vegetables filling Extras to main courses: Medley of salads Medley of boiled vegetables Rice Optionally Hot drinks: Freshly-brewed coffee with milk and a choice of: sugar or sweetener Tea - various flavours with lemon, sugar or sweetener Cold drinks: Orange, apple, black currant juices PROPOSAL 2 Main course: Chicken fillet with mozzarella and basil Pork escalopes with camembert sauce Oriental vegetables with soy sauce Extras to main courses: Boiled potatoes with dill Silesian dumplings Mix of lettuces with vegetables and vinaigrette dressing Fried beetroots Desserts: Selection of home-made cakes (apple pies, cheese cake, Brownie, cream cake) Optionally Hot drinks: Freshly-brewed coffee with milk and a choice of: sugar or sweetener Tea - various flavours with lemon, sugar or sweetener Cold drinks: Orange, apple, black currant juices Smaki Miasta Catering al. Niepodległości 147, 02-555 Warszawa | tel. 515 125 263, [email protected] www.smaki-miasta.pl PROPOSAL 3 Soup: Tomato cream soup with herb croutons Main course: Grilled chicken fillet in thyme sauce Pork tenderloin in mushroom sauce Cod in tomatoes and onion Pepper stuffed with vegetables and baked with cheese Extras to main courses: Roasted potatoes Polish potato dumplings (kopytka) Cauliflower gratine Medley of salads Desserts: -

Download PDF Menu

Sandwiches Soups hot and made from scratch in house with bread All Sandwiches come with Chips 8oz Cup – $3.77 16oz Bowl – $5.66 Kielbasa on a Bun – $7.55 32oz Quart – $9.43 (to-go only) grilled polish style kielbasa served with onions and sauerkraut on a roll Chicken Noodle Ham Sandwich – $7.55 *Beet – Red Borscht deli smoked ham, swiss cheese, spicy mustard, *Zurek – Sour Rye lettuce and tomato on light rye Polish Bean Dill Pickle Turkey Sandwich – $7.55 sliced turkey breast, swiss cheese, lettuce, tomato AUTHENTIC POLISH and mayo on light rye Dessert CUISINE Reuben – $8.49 Vanilla Ice Cream – $2.12 corned beef, swiss cheese, home-made sauerkraut and thousand island dressing served on marble rye Apple Cake – $4.72 8418 M-119 Turkey Reuben – $8.49 Single Crepe – $2.12 Harbor Springs, MI 49740 turkey breast, swiss cheese, home-made sauerkraut Three Crepes – $5.66 and thousand island dressing served on marble rye crepe fillings: raspberry, strawberry, blueberry, cherry, blackberry, creamy cheesecake, (231) 838 – 5377 Rachel Reuben – $8.49 Dutch chocolate cheesecake or Nutella turkey breast, swiss cheese, home-made coleslaw and thousand island dressing served on marble rye Kids’ Corner www.famouspolishkitchen.com Rissole Burger Sandwich – $8.49 two ground pork patties, served with cheese, Grilled Cheese – $4.72 Dine in or take out. onions, tomato, lettuce and mayo on a roll American cheese melted on wheat with a bag of Call us to organize catering for special chips or apple sauce occasions, such as weddings, graduation Club Sandwich – $8.49 ham, turkey breast, bacon, lettuce, tomato and Peanut Butter and Jelly – $4.72 parties and more! Or to place call-in orders. -

Kabanosy Our National Specialty Unia Europejska Zmieniła Polskie Rybactwo the European Union Changed Polish Fishery

ISSN 1232-9541 Zima Winter 2014/2015 Stephane Antiga: Polubiłem polskie zupy I've grown fond of Polish soups Europa wraca do korzeni Europe is returning to its roots nasz narodowy specjał Kabanosy our national specialty Unia Europejska zmieniła polskie rybactwo The European Union changed Polish fishery Marek Sawicki MiniSter rolnictwa i rozwoju wSi MiniSter of agriculture and rural developMent Zimowe wydanie kwartalnika „Polish Food” zamyka stary rok i jednocześnie otwiera nowy. Ten odchodzący z wielu powodów był wyjątkowy. Przede wszystkim był to rok wielu ważnych dla Polski rocznic. Winter issue of the quarterly "Polish Food" closes the old year and at the same time opens the new one. The one that is almost behind us has been unique for several reasons. Mainly, it has been a year of many important anniversaries for Poland. szanowni Państwo! Ladies and GentLemen! Dwadzieścia pięć lat temu odbyły się pamiętne częścio- Twenty five years ago, the memorable, partially free, elections wo wolne wybory. To był początek przemian nie tylko tu, nad took place. It was a beginning for changes not only here, in Poland, Wisłą, ale w całej Europie. Konsekwencją tamtych wyborów but in whole Europe. Those elections resulted in far-reaching social, były daleko idące zmiany społeczne, gospodarcze i politycz- economic and political changes. Poland, just like other countries of sne. Polska, jak i inne kraje tego regionu, powróciła do Europy.l this region, returned to Europe. In 2014 we have celebrated the W 2014 roku obchodziliśmy dziesiątą rocznicę obecności Polski tenth anniversary of Polish presence in the European community. w europejskiej wspólnocie. -

Bigos - Polish Hunter’S Stew Country of Origin: Poland1 Main Course Dish

Bigos - Polish Hunter's Stew Country of origin: Poland1 Main Course dish. Hearty game stew in a rich sauce, quantities are for 8 or more. Nearest related recipe seems to be Italian2 Bollito Misto3 This recipe is packed full of flavour and not really for the faint hearted chef or diner. If you have an energetic lifestyle then this is for you. Ingredients Top, tail, skin and chop the onions. Trim and chop large the mushrooms. 4 rashers fatty bacon Peel and core the apples and chop into chunks. 500 gm pork meat 1 kg venison pieces Cooking 4 cloves garlic 4 medium onions Pre-heat the oven to gas mark 3. 30 ml paprika Fry the bacon in a Dutch oven or le Creuset pan, 250 gm field mushrooms to render the fat, then add the pieces of pork and venison, garlic, onions, paprika, and mush- 500 ml beef stock rooms. Stir fry until the meat is browned{about 30 gm FAIRTRADE chutney 5 minutes. 2 large cans of chopped tomatoes Add the stock, the chutney, tomatoes, bay leaves, sauerkraut, and apples, and bring to a 4 FAIRTRADE bay leaves boil. 400 ml sauerkraut Remove from the heat and check saesoning, 4 FAIRTRADE apples adding salt and pepper to taste. 200 gm cooked ham Put the pot into the oven and bake for 2 and 1/2 hours. 6 Polish sausages (Kielbasa) Add the ham and sausages and bake for a further 30 minutes. Method Preparation To serve Chop the bacon into bite sized pieces. When ready to serve, remove bay leaves and again check the taste for seasoning.