The Military Footprint of the Presidio of San Francisco By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BINONDO FOOD TRIP (4 Hours)

BINONDO FOOD TRIP (4 hours) Eat your way around Binondo, the Philippines’ Chinatown. Located across the Pasig River from the walled city of Intramuros, Binondo was formally established in 1594, and is believed to be the oldest Chinatown in the world. It is the center of commerce and trade for all types of businesses run by Filipino-Chinese merchants, and given the historic reach of Chinese trading in the Pacific, it has been a hub of Chinese commerce in the Philippines since before the first Spanish colonizers arrived in the Philippines in 1521. Before World War II, Binondo was the center of the banking and financial community in the Philippines, housing insurance companies, commercial banks and other financial institutions from Britain and the United States. These banks were located mostly along Escólta, which used to be called the "Wall Street of the Philippines". Binondo remains a center of commerce and trade for all types of businesses run by Filipino- Chinese merchants and is famous for its diverse offerings of Chinese cuisine. Enjoy walking around the streets of Binondo, taking in Tsinoy (Chinese-Filipino) history through various Chinese specialties from its small and cozy restaurants. Have a taste of fried Chinese Lumpia, Kuchay Empanada and Misua Guisado at Quick Snack located along Carvajal Street; Kiampong Rice and Peanut Balls at Café Mezzanine; Kuchay Dumplings at Dong Bei Dumplings and the growing famous Beef Kan Pan of Lan Zhou La Mien. References: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binondo,_Manila TIME ITINERARY 0800H Pick-up -

Encountering Nicaragua

Encountering Nicaragua United States Marines Occupying Nicaragua, 1927-1933 Christian Laupsa MA Thesis in History Department of Archeology, Conservation, and History UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2011 ii Encountering Nicaragua United States Marines Occupying Nicaragua, 1927-1933 Christian Laupsa MA Thesis in History Department of Archeology, Conservation, and History University of Oslo Spring 2011 iii iv Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................... v Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................... viii 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Topic .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Research Questions ............................................................................................................................. 3 Delimitations ....................................................................................................................................... 3 The United States Marine Corps: a very brief history ......................................................................... 4 Historiography .................................................................................................................................... -

Trinity Sunday, Year A

Trinity Sunday, Year A Reading Difficult Texts with the God of Love and Peace We all read Bible passages in the light of our own experiences, concerns and locations in society. It is not surprising that interpretations of the Bible which seem life-giving to some readers will be experienced by other readers as harmful or oppressive. What about these passages that are used to speak of the concept of the Trinity? This week's lectionary Bible passages: Genesis 1:1-2:4a; Psalm 8; 2 Corinthians 13:11-13; Matthew 28:16-20 Who's in the Conversation A conversation among the following scholars and pastors “Despite the desire of some Christians to marginalize those who are different, our faith calls us to embrace the diversity of our personhood created by God and celebrate it.” Bentley de Bardelaben “People often are unable to see „the goodness of all creation‟ because of our narrow view of what it means to be human and our doctrines of sin, God and humanity." Valerie Bridgeman Davis “By affirming that we, too, are part of God‟s „good creation,‟ lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people of faith begin to take responsibility for fostering love and peace throughout creation." Ken Stone “When we creep in the direction of believing that we absolutely know God, Christ, and the Holy Spirit, we have not only limited the Trinity, but also sown the seeds of hostility and elitism. We need to be reminded of the powerful, mysterious and surprising ways that the Trinity continues to work among all creation." Holly Toensing What's Out in the Conversation A conversation about this week's lectionary Bible passages LGBT people know that Scripture can be used for troubling purposes. -

A Confusion of Institutions: Spanish Law and Practice in a Francophone Colony, Louisiana, 1763-Circa 1798

THE TULANE EUROPEAN AND CIVIL LAW FORUM VOLUME 31/32 2017 A Confusion of Institutions: Spanish Law and Practice in a Francophone Colony, Louisiana, 1763-circa 1798 Paul E Hoffman* I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 1 II. THE ECONOMIC SYSTEM AND LOCAL LAW AND ORDER .................... 4 III. SLAVERY ............................................................................................. 13 IV. CONCLUSION ...................................................................................... 20 I. INTRODUCTION French Louisiana had been a thorn in the flank of Spain’s Atlantic Empire from its founding in 1699. Failure to remove that thorn in 1699 and again in 1716, when doing so would have been comparatively easy and Spanish naval forces were positioned to do so, meant that by 1762 the wound had festered, so that the colony had become what La Salle, Iberville, Bienville, and their royal masters had envisioned: a smuggling station through which French goods reached New Spain and Cuba and their goods—dye stuffs and silver mostly—reached France and helped to pay the costs of a colony that consumed more than it produced, at least so 1 far as the French crown’s finances were concerned. * © 2017 Paul E Hoffman. Professor Emeritus of History, Louisiana State University. 1. I have borrowed the “thorn” from ROBERT S. WEDDLE, THE FRENCH THORN: RIVAL EXPLORERS IN THE SPANISH SEA, 1682-1762 (1991); ROBERT S. WEDDLE, CHANGING TIDES: TWILIGHT AND DAWN IN THE SPANISH SEA, 1763-1803 (1995) (carries the story of explorations). The most detailed history of the French colony to 1731 is the five volumes of A History of French Louisiana: MARCEL GIRAUD, 1-4 HISTOIRE DE LA LOUISIANA FRANÇAISE (1953-74); 1 A HISTORY OF FRENCH LOUISIANA: THE REIGN OF LOUIS XIV, 1698-1715 (Joseph C. -

The Archaeology of Time Travel Represents a Particularly Significant Way to Bring Experiencing the Past the Past Back to Life in the Present

This volume explores the relevance of time travel as a characteristic contemporary way to approach (Eds) & Holtorf Petersson the past. If reality is defined as the sum of human experiences and social practices, all reality is partly virtual, and all experienced and practised time travel is real. In that sense, time travel experiences are not necessarily purely imaginary. Time travel experiences and associated social practices have become ubiquitous and popular, increasingly Chapter 9 replacing more knowledge-orientated and critical The Archaeology approaches to the past. The papers in this book Waterworld explore various types and methods of time travel of Time Travel and seek to prove that time travel is a legitimate Bodil Petersson and timely object of study and critique because it The Archaeology of Time Travel The Archaeology represents a particularly significant way to bring Experiencing the Past the past back to life in the present. in the 21st Century Archaeopress Edited by Archaeopress Archaeology www.archaeopress.com Bodil Petersson Cornelius Holtorf Open Access Papers Cover.indd 1 24/05/2017 10:17:26 The Archaeology of Time Travel Experiencing the Past in the 21st Century Edited by Bodil Petersson Cornelius Holtorf Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 500 1 ISBN 978 1 78491 501 8 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2017 Economic support for publishing this book has been received from The Krapperup Foundation The Hainska Foundation Cover illustrations are taken from the different texts of the book. See List of Figures for information. -

Alaska Beyond Magazine

The Past is Present Standing atop a sandstone hill in Cabrillo National Monument on the Point Loma Peninsula, west of downtown San Diego, I breathe in salty ocean air. I watch frothy waves roaring onto shore, and look down at tide pool areas harboring creatures such as tan-and- white owl limpets, green sea anemones and pink nudi- branchs. Perhaps these same species were viewed by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in 1542 when, as an explorer for Spain, he came ashore on the peninsula, making him the first person from a European ocean expedition to step onto what became the state of California. Cabrillo’s landing set the stage for additional Span- ish exploration in the 16th and 17th centuries, followed in the 18th century by Spanish settlement. When I gaze inland from Cabrillo National Monument, I can see a vast range of traditional Native Kumeyaay lands, in- cluding the hilly area above the San Diego River where, in 1769, an expedition from New Spain (Mexico), led by Franciscan priest Junípero Serra and military officer Gaspar de Portolá, founded a fort and mission. Their establishment of the settlement 250 years ago has been called the moment that modern San Diego was born. It also is believed to represent the first permanent European settlement in the part of North America that is now California. As San Diego commemorates the 250th anniversary of the Spanish settlement, this is an opportune time 122 ALASKA BEYOND APRIL 2019 THE 250TH ANNIVERSARY OF EUROPEAN SETTLEMENT IN SAN DIEGO IS A GREAT TIME TO EXPLORE SITES THAT HELP TELL THE STORY OF THE AREA’S DEVELOPMENT by MATTHEW J. -

Vigía: the Network of Lookout Points in Spanish Guam

Vigía: The Network of Lookout Points in Spanish Guam Carlos Madrid Richard Flores Taitano Micronesian Area Research Center There are indications of the existence of a network of lookout points around Guam during the 18th and 19th centuries. This is suggested by passing references and few explicit allusions in Spanish colonial records such as early 19th Century military reports. In an attempt to identify the sites where those lookout points might have been located, this paper surveys some of those references and matches them with existing toponymy. It is hoped that the results will be of some help to archaeologists, historic preservation staff, or anyone interested in the history of Guam and Micronesia. While the need of using historic records is instrumental for the abovementioned purposes of this paper, focus will be given to the Chamorro place name Bijia. Historical evolution of toponymy, an area of study in need of attention, offers clues about the use or significance that a given location had in the past. The word Vigía today means “sentinel” in Spanish - the person who is responsible for surveying an area and warn of possible dangers. But its first dictionary definition is still "high tower elevated on the horizon, to register and give notice of what is discovered". Vigía also means an "eminence or height from which a significant area of land or sea can be seen".1 Holding on to the latter definition, it is noticeable that in the Hispanic world, in large coastal territories that were subjected to frequent attacks from the sea, the place name Vigía is relatively common. -

2016 NHPA Annual Report

January 30, 2017 Julianne Polanco, State Historic Preservation Officer Attention: Mark Beason Office of Historic Preservation 1725 23rd Street, Suite 100 Sacramento, CA 95816 John Fowler, Executive Director Attention: Najah Duvall Office of Federal Agency Programs Advisory Council on Historic Preservation 401 F Street NW, Suite 308 Washington, DC 20001 Laura Joss, Regional Director Attention: Elaine Jackson-Retondo National Park Service – Pacific West Regional Office 333 Bush Street San Francisco, CA 94104 Craig Kenkel, Acting Superintendent Attention: Steve Haller Golden Gate National Recreation Area Building 201 Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94123 Reference: 2016 Annual Report on Activities under the 2014 Presidio Trust Programmatic Agreement, the Presidio of San Francisco National Historic Landmark District, San Francisco, California Pursuant to Stipulation XIV of the Presidio Trust Programmatic Agreement (PTPA, 2014), enclosed is the 2016 Annual Report of activities conducted under that PA. In 2016, the Presidio Trust celebrated the 50th anniversary of the National Historic Preservation Act alongside the nation’s preservation community with a sense of reflection, gratitude and forward-looking purpose. We were also pleased to commemorate the centennial anniversary of the National Park Service, and thank our partners for their trailblazing role in preserving American cultural heritage here in California and beyond. Our principal activity for recognizing these milestones was to host the 41st annual California Preservation Foundation conference at the Presidio in April. At the conference we were enormously proud to be recognized by CPF president Kelly Sutherlin McLeod as “perhaps the biggest preservation success story of the 20th century”, praise that would not be possible without the contributions of our partner agencies, tenants and park users. -

Comparison of Spanish Colonization—Latin America and the Philippines

Title: Comparison of Spanish Colonization—Latin America and the Philippines Teacher: Anne Sharkey, Huntley High School Summary: This lesson took part as a comparison of the different aspects of the Spanish maritime empires with a comparison of Spanish colonization of Mexico & Cuba to that of the Philippines. The lessons in this unit begin with a basic understanding of each land based empire of the time period 1450-1750 (Russia, Ottomans, China) and then with a movement to the maritime transoceanic empires (Spain, Portugal, France, Britain). This lesson will come after the students already have been introduced to the Spanish colonial empire and the Spanish trade systems through the Atlantic and Pacific. Through this lesson the students will gain an understanding of Spanish systems of colonial rule and control of the peoples and the territories. The evaluation of causes of actions of the Spanish, reactions to native populations, and consequences of Spanish involvement will be discussed with the direct correlation between the social systems and structures created, the influence of the Christian missionaries, the rebellions and conflicts with native populations between the two locations in the Latin American Spanish colonies and the Philippines. Level: High School Content Area: AP World History, World History, Global Studies Duration: Lesson Objectives: Students will be able to: Compare the economic, political, social, and cultural structures of the Spanish involvement in Latin America with the Spanish involvement with the Philippines Compare the effects of mercantilism on Latin America and the Philippines Evaluate the role of the encomienda and hacienda system on both regions Evaluate the influence of the silver trade on the economies of both regions Analyze the creation of a colonial society through the development of social classes—Peninsulares, creoles, mestizos, mulattos, etc. -

Italian Bookshelf

This page intentionally left blank x . ANNALI D’ITALIANISTICA 37 (2019) Italian Bookshelf www.ibiblio.org/annali Andrea Polegato (California State University, Fresno) Book Review Coordinator of Italian Bookshelf Anthony Nussmeier University of Dallas Editor of Reviews in English Responsible for the Middle Ages Andrea Polegato California State University, Fresno Editor of Reviews in Italian Responsible for the Renaissance Olimpia Pelosi SUNY, Albany Responsible for the 17th, 18th, and 19th Centuries Monica Jansen Utrecht University Responsible for 20th and 21st Centuries Enrico Minardi Arizona State University Responsible for 20th and 21st Centuries Alessandro Grazi Leibniz Institute of European History, Mainz Responsible for Jewish Studies REVIEW ARTICLES by Jo Ann Cavallo (Columbia University) 528 Flavio Giovanni Conti and Alan R. Perry. Italian Prisoners of War in Pennsylvania, Allies on the Home Front, 1944–1945. Lanham, MD: Fairleigh Dickinson Press, 2016. Pp. 312. 528 Flavio Giovanni Conti e Alan R. Perry. Prigionieri di guerra italiani in Pennsylvania 1944–1945. Bologna: Il Mulino, 2018. Pp. 372. 528 Flavio Giovanni Conti. World War II Italian Prisoners of War in Chambersburg. Charleston: Arcadia, 2017. Pp. 128. Contents . xi GENERAL & MISCELLANEOUS STUDIES 535 Lawrence Baldassaro. Baseball Italian Style: Great Stories Told by Italian American Major Leaguers from Crosetti to Piazza. New York: Sports Publishing, 2018. Pp. 275. (Alan Perry, Gettysburg College) 537 Mario Isnenghi, Thomas Stauder, Lisa Bregantin. Identitätskonflikte und Gedächtniskonstruktionen. Die „Märtyrer des Trentino“ vor, während und nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg. Cesare Battisti, Fabio Filzi und Damiano Chiesa. Berlin: LIT, 2018. Pp. 402. (Monica Biasiolo, Universität Augsburg) 542 Journal of Italian Translation. Ed. Luigi Bonaffini. -

Spain Builds an Empire

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=TX-A SECTION 3 Spain Builds an TEKS 1A, 2A Empire What You Will Learn… If YOU were there... Main Ideas You are an Aztec warrior living in central Mexico in the 1500s. You 1. Spanish conquistadors con- are proud to serve your ruler, Moctezuma II. One day several hun- quered the Aztec and Inca empires. dred foreigners arrive on your shores. They are pale, bearded men, 2. Spanish explorers traveled and they have strange animals and equipment. through the borderlands of New Spain, claiming more From where do you think these strangers have come? land. 3. Spanish settlers treated Native Americans harshly, forcing them to work on plantations and in mines. BUILDING BACKGROUND Spain sent many expeditions to the Americas. Like explorers from other countries, Spanish explorers The Big Idea claimed the land they found for their country. Much of this land was Spain established a large already filled with Native American communities, however. empire in the Americas. Key Terms and People Spanish Conquistadors conquistadors, p. 46 The Spanish sent conquistadors (kahn-kees-tuh-DAWRS), soldiers Hernán Cortés, p. 46 who led military expeditions in the Americas. Conquistador Hernán Moctezuma II, p. 46 Cortés left Cuba to sail to present-day Mexico in 1519. Cortés Francisco Pizarro, p. 47 had heard of a wealthy land to the west ruled by a king named encomienda system, p. 50 Moctezuma II (mawk-tay-SOO-mah). plantations, p. 50 Bartolomé de Las Casas, p. 51 Conquest of the Aztec Empire Moctezuma ruled the Aztec Empire, which was at the height of its power in the early 1500s. -

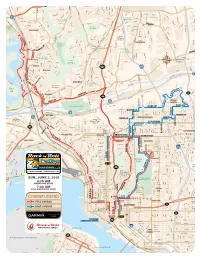

COURSE LEGEND L M T T G a N a a a a N H M a W Dr Ct H W a V 274 N R O E U Tol V I V O a P a a a D Ac E H If E Y I V V Ca E D D R E Ur St G Beadnell Way Armo a R F E

C a r d y a e Ca n n W n S o o in g n t r D i to D n S r n L c t o i u D e n c S n ate K n o r e g R a G i e l ow d l c g s A e C e id r v e w S v l e Co R e e f n mplex Dr d v a e a v l h B e l l ld t s A h o C J Triana S B a a A e t A e S J y d nt a s i a e t m v e gu e L r S h a s e e e R Ave b e t Lightwave d A A v L t z v a e M v D l A sa Ruffin Ct M j e n o r t SUN., JUNE 2, 2013 B r n e d n o Mt L e u a a M n r P b r D m s l a p l D re e a A y V i r r h r la tt r i C a t n Printwood Way i M e y r e d D D S C t r M v n a w I n C a d o C k Vickers St e 6:15 AM a o l l e Berwick Dr O r g c n t w m a e h i K i n u ir L i d r e i l a Engineer Rd J opi Pl d Cl a n H W r b c g a t i Olive Spectrum Center MARATHON STy ART m y e e Blvd r r e Ariane Dr a y o u o D u D l S A n L St Cardin Buckingham Dr s e a D h a y v s r a Grove R Soledad Rd P e n e R d r t P Mt Harris Dr d Opportunity Rd t W a Dr Castleton Dr t K r d V o e R b S i F a l a c 7:00 AM e l m Park e m e l w a Mt Gaywas Dr l P o a f l h a e D S l C o e o n HALF-MARATHON START t o t P r o r n u R n D p i i Te ta r ch Way o A s P B r Dagget St e alb B d v A MT oa t D o e v Mt Frissell Dr Arm rs 163 e u TIERRASANTA BLVD R e e s D h v v r n A A Etna r ser t t a our Av S y r B A AVE LBO C e i r e A r lla Dr r n o M b B i a J Q e e r Park C C L e h C o u S H a o te G M r Orleck St lga a t i C t r a t H n l t g B a p i S t E A S o COURSE LEGEND l M t t g a n a a a a n H a w M Dr Ct h w A v 274 n r o e u Tol v i v o a P A A a D ac e h if e y ica v v e D D r e ur St g Beadnell Way Armo