Five Type Families

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Catalogue of the Wood Type at Rochester Institute of Technology David P

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 11-1-1992 A Catalogue of the wood type at Rochester Institute of Technology David P. Wall Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Wall, David P., "A Catalogue of the wood type at Rochester Institute of Technology" (1992). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. School ofPrinting Management and Sciences Rochester Institute ofTechnology Rochester, New York Certificate ofApproval Master's Thesis This is to Certify that the Master's Thesis of David P. Wall With a major in Graphic Arts Publishing has been approved by the Thesis Committee as satisfactory for the thesis requirement for the Master ofScience degree at the convocation of DECEMBER 1992 Da,e Thesis Committee: David Pankow Thesis Advisor Marie Freckleton Graduate Program Coordinator George H. Ryan Direcmr or Designa[e A Catalogue of the Wood Type at Rochester Institute of Technology by David P. Wall A thesis project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the School of Printing Management and Sciences in the College of Graphic Arts and Photography of the Rochester Institute ofTechnology November 1992 Project Advisor: Professor David Pankow Introduction type,' When Adobe Systems introduced in 1990 their first digital library of 'wood the event marked the latest step forward in a tradition dating back to 1828, when Darius Wells, ofNew Wells' York City, perfected the equipment and techniques needed to mass produce wood type. -

Jul 9 1975 -2

GENERATION OF ROMAN PRINTED FONTS by Philippe J.M. Coueignoux M.S., Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1973) SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 1975 Signature of Author........'... .ffV ... 4~...... ......v Department of Electrical Engineering, June Certi fied by.............................................0 a 0 a 00 0 0 Thesis Supervisor Accepted b0 ' Chairman, Departmental Committe&6n Graduate Students JUL 9 1975 -2- GENERATION OF ROMAN PRINTED FONTS by Philippe J.-M. Coueignoux Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science on May the 23rd, 1975, in partial fulfill- ment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ABSTRACT Three contributions are made to the generation of Roman printed fonts: a descriptive model, a generating program, CSD, and a line setting program, FRANCE. The model is based on a linguistic study of the con- sistency of Roman printed characters. Characters are de- composed into primitives. To represent a letter by a char- acter, one uses a specific combination of primitives; a grammar is given, which governs these combinations within the Roman style. The repeated use of the same drawing to represent a primitive in more than one combination differ- entiates the characters of a font from other fonts; further- more, parameters are used to specify the drawings and there exist relationships among the parameters for the different drawings of a font. Related parameters are gathered into families; global transformations for each of the families well describe elementary operations on fonts like boldening, size variations, etc. -

History of Moveable Type

History of Moveable Type Johannes Gutenberg invented Moveable Type and the Printing Press in Germany in 1440. Moveable Type was first made of wood and replaced by metal. Example of moveable type being set. Fonts were Type set on a printing press. organized in wooden “job cases” by Typeface, Caps and Lower Case, and Point Size. Typography Terms Glyphs – letters (A,a,B,b,C,c) Typeface – The aesthetic design of an alphabet. Helvetica, Didot, Times New Roman Type Family – The range of variations and point size available within one Typeface. Font (Font Face) – The traditional term for the complete set of a typeface as it relates to one point size (Font Face: Helvetica, 10 pt). This would include upper and lower case glyphs, small capitals, bold and italic. After the introduction of the computer, the word Font is now used synonymously with the word Typeface, i.e. “What font are you using? Helvetica!” Weight – the weight of a typeface is determined by the thickness of the character outlines relative to their height (Hairline, Thin, Ultra-light, Extra-light, Light, Book, Regular, Roman, Medium, Demi-bold, Semi-bold, Bold, Extra-bold, Heavy, Black, Extra-black, Ultra-black). Point Size – the size of the typeface (12pt, 14pt, 18pt). Points are the standard until of typographic measurement. 12 points = 1 pica, 6 picas = 72 points = 1 inch. (Example right) A general rule is that body copy should never go below 10pt and captions should never be less than 8pt. Leading – or line spacing is the spacing between lines of type. In metal type composition, actual pieces of lead were inserted between lines of type on the printing press to create line spacing. -

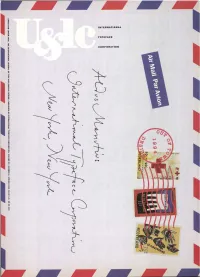

INTERNATIONAL TYPEFACE CORPORATION, to an Insightful 866 SECOND AVENUE, 18 Editorial Mix

INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION TYPEFACE UPPER AND LOWER CASE , THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF T YPE AND GRAPHI C DESIGN , PUBLI SHED BY I NTE RN ATIONAL TYPEFAC E CORPORATION . VO LUME 2 0 , NUMBER 4 , SPRING 1994 . $5 .00 U .S . $9 .90 AUD Adobe, Bitstream &AutologicTogether On One CD-ROM. C5tta 15000L Juniper, Wm Utopia, A d a, :Viabe Fort Collection. Birc , Btarkaok, On, Pcetita Nadel-ma, Poplar. Telma, Willow are tradmarks of Adobe System 1 *animated oh. • be oglitered nt certain Mrisdictions. Agfa, Boris and Cali Graphic ate registered te a Ten fonts non is a trademark of AGFA Elaision Miles in Womb* is a ma alkali of Alpha lanida is a registered trademark of Bigelow and Holmes. Charm. Ea ha Fowl Is. sent With the purchase of the Autologic APS- Stempel Schnei Ilk and Weiss are registimi trademarks afF mdi riot 11 atea hmthille TypeScriber CD from FontHaus, you can - Berthold Easkertille Rook, Berthold Bodoni. Berthold Coy, Bertha', d i i Book, Chottiana. Colas Larger. Fermata, Berthold Garauannt, Berthold Imago a nd Noire! end tradematts of Bern select 10 FREE FONTS from the over 130 outs Berthold Bodoni Old Face. AG Book Rounded, Imaleaa rd, forma* a. Comas. AG Old Face, Poppl Autologic typefaces available. Below is Post liedimiti, AG Sitoploal, Berthold Sr tapt sad Berthold IS albami Book art tr just a sampling of this range. Itt, .11, Armed is a trademark of Haas. ITC American T}pewmer ITi A, 31n. Garde at. Bantam, ITC Reogutat. Bmigmat Buick Cad Malt, HY Bis.5155a5, ITC Caslot '2114, (11 imam. -

Franklin Gothic: from Benton to Berlow

NUMBER TWO Franklin Gothic: from Benton to Berlow Sans serif, or gothic, typefaces became popular for advertising and promotional work in 19th century America. Their bold letterforms, brassy characteristics and efficient use of space were sought after then, just as they are now. By the time American Type Founders (ATF) was formed in 1892, more than 50 different sans serif faces were offered by the major American type suppliers. First Franklin Designs The Franklin Gothic™ typeface was the third in a series of sans serif faces designed after ATF was founded. In the early 1900s, Morris Fuller Benton, who was in charge of typeface development for ATF at the time, began to create the type designs that would influence American type design for more than 40 years. Globe Gothic was his first sans serif design, which was followed shortly thereafter by Alternate Gothic. Around 1902, Franklin Gothic was cut, although it was not released as a font of metal type until 1905. As he designed Franklin Gothic, Benton was likely influenced by the earlier sans serif designs released in Germany. Berthold had issued the Akzidenz Grotesk® series of typefaces (later known to American printers as “Standard”) in 1898. Akzidenz Grotesk inspired the cutting of Reform Grotesk by the Stempel foundry of Frankfurt in 1903, and the Venus™ series of typefaces by the Bauer foundry, also of Frankfurt, in 1907. A Small Family At first, Benton drew only a single roman design for Franklin Gothic. However, this typeface caught the imagination of printers of the time, and ATF was compelled to add more variants to make a small type family. -

Copyrighted Material

ABA form Bierma, Wigger, 103 Cheltenham family, 46, 46 communication, 70–74, 115 Bill, Max, 20, 92 Chimero, Frank, 147 typographic grids, 106–107 Bitstream, 24 Chisel, 32, 32 Academy of Art University, 205 Blackburn, Bruce, 23 Chiu, Chiu-Ping, 213 Accented characters, 35, 35 “Block style,” 18 Chromolithography, 15 Acropolis (Athens, Greece), 3 Bodoni, 34, 76 Chukwu, Chinedue, 221 Adobe, 25 Bodoni, Giambattista, 11, 12, 307 Chwast, Seymour, 22, 23 Adobe Garamond, 26, 35, 35 Bodoni Italic, 46, 46 Cincinnati, University of, 194, 198 Adobe Systems, Inc., 133, 135 Bongartz, Veronica, 156 Clarendon type, 14 Akkurat, 181 Bonnell, Bill, 24 Clarkson, Larry, 211 Aldine Press, 7 Boom, Irma, 27 Coates, Stephen, 122 Alestra, Anthony, 197 Boston University, 190 Cody, Mike, 138 Alphabets. See also Letter Bowl, 32, 33 Colines, Simon de, 9, 252, 253 Bayer’s universal, 19 Boyle, Robert, 50 Colley, David, 74, 110, 110, 118, 120, 200 defined, 31 Bradley, Will, 17 Collins, Gail, 50 legibility, 76, 76 Brainstorming, 220 Color, legibility, 82– 84 Phoenician, 3 Brancusi, Constantin, 19 Column Index Angle, typefaces, 46, 46 Brandt, Erik, 216 typographic grid, 100 Anthony, Carol, 115 Brodovitch, Alexey, 20 typographic syntax, 56, 58–60 Page numbers in italic refer Antialiasing, legibility, 82 Brody, Neville, 26 Column interval, grids, 100 to illustrations Apeloig, Philippe, 27 Brueggenjohann, Jean, 61, 202 Communication. See also Typographic Apex, 32, 33 Bruner, Paul, 204 syntax Apple Computer, 135 Brush writing, 3, 32 ABA form, 70–73 Arch of Constantine (Rome), 4 Buenos Aires Underground (Subte) typographic message, 112–124 Arm, 32, 33 176–179 visual hierarchy, 68 Armstrong, Frank, 50, 51, 52, 55, 55, Bukhshaisha, Fatima, 205 Computer. -

Bookmania Specimen

A Fresh Revival of an Old Classic from Mark SimonSon Studio Light Light Italic Regular Regular Italic Semibold Semibold Italic Bold Bold Italic Black Black Italic &Bookmania One might wOnder: Why bother? Bookman has had its day. It’s a has-been. Some might argue that it’s no great loss. But I believe it’s a typographical gem that’s never been properly revived. itC’s redesign in the Seventies took it so far from its roots that it should have been called something else. But that’s the “Bookman” we’ve been stuck with—like it or not—for a long time. The original, for the most part, has been lost to us. My aim was to go back to the earlier Bookmans and make a typeface that would restore the dignity (as well as frivolity) that was lost. As with any revival, it’s an interpretation. I’ve leaned heavily toward the more refined look of the display sizes of the older Bookmans. Nevertheless, it also works well for text, although the effect is different than the old Bookmans at smaller sizes. (I hope to do a Bookmania Text someday that has the look and feel of the old text sizes.) I tried to picture what AtF’s Morris Fuller Benton would have done if he had developed Bookman Oldstyle the way he did Cheltenham Oldstyle. Bookman Oldstyle (and most later Bookmans) had a certain unpolished look. There is some charm to this, but I wanted to see the same fit and finish that Benton gave to his Cheltenham and Century faces. -

Classi Cation of Type

1 Typography Classicationtypeface classification of Type GARAMOND Aa OLDSTYLE TRANSITIONAL MODERN SLAB SERIF SAN SERIF Source: Thinking with Type: A Critical Guide for Designers, Writers, and Editors: Ellen Lupton Source: Ellen Lupton, Thinking with Type (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2010), 46. 2 Typography Classication of Type Classications of type you will need to become familiar with for this class. e typographic form has evolved and in order to eectively analyze this typographic evolution, the design of type characters over the last ve and a half centuries is most oen broken down into classications of common visual Characteristics, called families of type: Old Style (15th-17th century) Example Typefaces: Bembo • Garamond • Caslon • Jenson Transitional (Neoclassical) (mid 18th century) Example Typefaces: Baskerville • Cheltenham • Bookman • Romain du Roi Modern (Didon) (late 18th century) Example Typefaces:: Bodoni • Didot • ITC Fenice Slab Serif (Egyptian) (19th century) Example Typefaces: Clarendon • Memphis • Rockwell • Century Sans Serif (19th-20th century) Example Typefaces: Futura • Helvetica • Universe • Akzidenz Grotesk • Frutiger Cursive Example Typefaces: Bickham • Edwardian Script ITC • Choc • Brush Script Display (19th-20th century) Example Typefaces: Leafy Glade • Plexifont • Chausson • Phosphate 3 Typography Old Style (15th-17th century) Example Typefaces: Bembo • Garamond • Caslon • Jenson OLDSTYLE CHARACTERISTICS • Designed in a time when inks and paper were coarse and type technology was still rather rough • Relatively thick strokes and heavily bracketed or curved serifs • Emulated classical calligraphy • Minimal variation of thick and thin strokes • Small, coarse serifs, oen with slightly concave bases • Small x-heights. • In the round strokes, the stress is diagonal, or oblique, as their designs mimic the hand-held angle of the pen nibs of the scribes. -

Americana Ancient Roman Antique Extended No. 53 Artcraft Italic

Serif There are three principal features of the roman face Americana Century Schoolbook Craw Clarendon MacFarland Van Dijck which were gradually modified in the three centuries Ancient Roman Century Schoolbook Italic Craw Clarendon Condensed MacFarland Condensed Van Dijck Italic from Jenson to Bodoni. In the earliest romans, the serifs were inclined and bracketed, that is to say, the Antique Extended No. 53 Cheltenham Craw Modern MacFarland Italic underpart of the serif was connected to the stem in a curve or by a triangular piece. On the upper case Artcraft Italic Cheltenham Bold Deepdene Italic Nubian the serifs were often thick slabs extending to both Baskerville Cheltenham Bold Condensed Eden Palatino Italic sides of the uprights. In the typical modern face serifs are thin, flat and unbracketed. In between the two Baskerville Italic Cheltenham Bold Extra Encore Palatino Semi-Bold extremes various gradations are found. In all early Condensed romans the incidence of colour or stress is diagonal, Bauer Bodoni Bold Engravers Roman Paramount Cheltenham Bold Italic while in the modern face it is vertical. If an O is Bembo Engravers Roman Bold Pencraft Oldstyle drawn with a broad-nibbed pen held at an angle to Cheltenham Bold Outline the paper, the two thickest parts of the letter will be Bembo ITalic Engravers Roman Shaded Rivoli Italic diagonally opposite. This was the manner in which Cheltenham Italic Bernhard Modern Roman Garamond Stymie Black the calligraphers of the fifteenth century drew an O; Clarendon Medium but by the year 1700 the writing masters, whose work Bernhard Modern Roman Italic Garamond Bold Stymie Bold was being reproduced in copper-engraved plates, had Cloister Oldstyle adopted the method of holding the pen at right angles Bodoni Garamond Bold Italic Stymie Bold Condensed to the paper, thus producing a vertical stress. -

Copyrighted Material

COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL 006_542514_ch01.indd6_542514_ch01.indd 1414 66/2/10/2/10 99:27:27 AAMM CHAPTER ONE A BRIEF HISTORY OF TYPE he story of type doesn’t begin with type per se, rather it starts with the beginning of mankind and civilization. Type has only existed for about 560 years, but its beginnings are rooted in the life of the caveman himself, as it was his developing needs and habits that led civiliza- tion on a path toward the evolution of the alphabet and subsequently the invention of type and printing. It is certainly possible to learn to use type effectively and tastefully without knowing its roots; but to fully understand and appreciate type today, it is important to know something of the past. Milestones in the history of type are highlighted throughout this chap- ter. Some of the dates, chronology, and details vary from source to source, but the spirit of the events remains the same. These events have taken mankind on a glorious ride from the crudest cave drawings to the bits and bytes of type in the digital age. SOUNDS TO SYMBOLS For many years, early humans communicated purely with sound. Verbal language–which is heard and not seen as opposed to visual language (or visible language, as it is often called)–has many limitations: it is gone the instant it is spoken and heard, and it is therefore temporary. Stories, history, and other information could not be passed on from generation to generation in a permanent way, only by direct word of mouth. The earliest attempts to record stories and ideas were through cave drawings; the fi rst known is dated around 25,000 bc. -

Eye Do What Does the New York Times Redesign Say About Its Self-Image? by Christopher Hawthorne

Slate | http://slate.msn.com/id/2090801/ 5 Nov. 2003 Eye Do What does the New York Times redesign say about its self-image? By Christopher Hawthorne Among the New York Times’ many longstanding quirks is the third person, bone-dry style the paper uses to write about itself. That tone, detached and a bit solemn, hardly wavers whether the paper is announcing a promotion or dissecting an in-house scandal. Last month’s unveiling of changes to the paper’s design was no different. “In place of a miscellany of headline typefaces that have accumulated in its columns over the last century,” an Oct. story reported, “the newspaper is settling on a single family, Cheltenham, in roman and italic version and various light and bold weights.” “Settling on a single family”: Along with adding a poetic touch to what might easily have been a boring press release of a story, that phrase neatly sums up what is, in essence, an affirmation from the Times of typographical monogamy. The paper has decided to stop playing around with a half-dozen different typefaces for its headlines and shack up with just one, a serif font called Cheltenham. (Serif typefaces are those with extra bits on the ends of most letters—the little lines that stick out from the tops of h’s and d’s and add a degree of formality. Sans-serif fonts, which are smoother and less stuffy and have been popular among graphic designers over the last five years or so, lack those strokes.) Design writers and Times addicts had no practical need for the announcement on page : Most of us noticed the new style as soon as we unfolded the paper the morning it went into effect. -

About Typeface Families

About Typeface Families By Allan Haley WHEN TYPEFACES WERE FIRST INVENTED, the notion of having a family of type hadn’t occurred to anyone. All fonts were simply roman designs. In the early 16th century, cursive – or italic (named after Italy, where the idea was popularized) – type was introduced. There were still no typeface families; romans were one style of type and italics were another – much like serif and sans serif. In the late 1700s, foundries began to characteristics of the parent design, release fonts in families – pairing roman but with individual variances. The and italic designs that matched each Cheltenham, Century, Cloister, and other in style. Later the concept of Stymie typeface families are just a few of typeface weights and proportions was the designs developed under Benton’s added to the typeface family mix. watchful eye. In the 20th century, type families were enlarged even further with the intro- Benton’s original vision has been duction of different designs such as modified and expanded several times condensed, expanded and outlined. over the decades. Type families have become larger, more diverse and better thought-out. Planning by the Numbers In 1957, the Swiss type designer Adrian Frutiger designed a new kind of type family. Because he felt that the traditional system of providing names – “bold,” “semi-bold,” “semi-bold condensed” and so on – was confusing Typical typeface family and outdated, he proposed a logical, systematic numbering scheme. In Frutiger’s system, each typeface was Modern Type Families given a two-digit suffix. The first digit The person generally credited with classified the alphabet weight, with conceiving the modern idea of a 3 indicating the lightest weight in the typeface family is Morris Fuller Benton, family and 9 the boldest.