Micrcxilms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Mexico New Mexico

NEW MEXICO NEWand MEXICO the PIMERIA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves NEW MEXICO AND THE PIMERÍA ALTA NEWand MEXICO thePI MERÍA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder © 2017 by University Press of Colorado Published by University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University. ∞ This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). ISBN: 978-1-60732-573-4 (cloth) ISBN: 978-1-60732-574-1 (ebook) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Douglass, John G., 1968– editor. | Graves, William M., editor. Title: New Mexico and the Pimería Alta : the colonial period in the American Southwest / edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves. Description: Boulder : University Press of Colorado, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016044391| ISBN 9781607325734 (cloth) | ISBN 9781607325741 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Spaniards—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. | Spaniards—Southwest, New—History. | Indians of North America—First contact with Europeans—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. -

RECTOR DE LA UNIVERSIDAD DE LA HABANA Juan Vela Valdés DIRECTOR Eduardo Torres-Cuevas SUBDIRECTOR Luis M

CASA DE ALTOS ESTUDIOS DON FERNANDO ORTIZ UNIVERSIDAD DE LA HABANA BIBLIOTECA DE CLÁSICOS CUBANOS RECTOR DE LA UNIVERSIDAD DE LA HABANA Juan Vela Valdés DIRECTOR Eduardo Torres-Cuevas SUBDIRECTOR Luis M. de las Traviesas Moreno EDITORA PRINCIPAL Gladys Alonso González DIRECTOR ARTÍSTICO Luis Alfredo Gutiérrez Eiró ADMINISTRADORA EDITORIAL Esther Lobaina Oliva Responsable de la edición: Diseño gráfico: Zaida González Amador Luis Alfredo Gutiérrez Eiró Realización y emplane: Composición de textos: Beatriz Pérez Rodríguez Equipo de Ediciones IC Todos los derechos reservados. © Sobre la presente edición: Ediciones IMAGEN CONTEMPORANEA, 2005; Colección Biblioteca de Clásicos Cubanos, No. 39 ISBN 959-7078-76-7 obra completa ISBN 959-7078-78-3 volumen II Ediciones IMAGEN CONTEMPORANEA Casa de Altos Estudios Don Fernando Ortiz, L y 27, CP 10400, Vedado, Ciudad de La Habana, Cuba Casa de Factoría, La Habana Vale la pena de referir (...) la serie de vicisitudes por que ha pasado la publicación de esta obra (...) dar a las prensas la parte que se ha encon- trado del volumen del infortunado historiador habanero... Carlos M. Trelles ADVERTENCIA En el tomo precedente se reimprimió nada más que la primera parte del Teatro Histórico del doctor Urrutia, sirviéndonos de la edición de 1876, con las enmiendas pertinentes, para cumplir el acuerdo adoptado por la Academia a solicitud de nuestro compañero el Dr. Francisco de Paula Co- ronado; y en este segundo y último tomo de las Obras del ilustre escritor habanero, se publican: la segunda parte del Teatro histórico, hasta ahora inédita, y el Compendio de Memorias, que si bien es cierto que empezó a editarse en esta Capital en 1791, como no se acabó de dar a luz, pues se interrumpió la publicación cundo estaba en la página 120, ni se reprodujo después en los 140 años que han transcurrido, casi puede tenérsele tam- bién por inédito. -

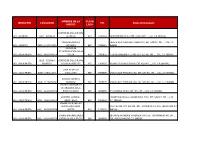

MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD NOMBRE DE LA UNIDAD CLAVE LADA TEL Domiciliocompleto

NOMBRE DE LA CLAVE MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD TEL DomicilioCompleto UNIDAD LADA CENTRO DE SALUD RURAL 001 - ACONCHI 0001 - ACONCHI ACONCHI 623 2330060 INDEPENDENCIA NO. EXT. 20 NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84920) CASA DE SALUD LA FRENTE A LA PLAZA DEL PUEBLO NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. 001 - ACONCHI 0003 - LA ESTANCIA ESTANCIA 623 2330401 (84929) UNIDAD DE DESINTOXICACION AGUA 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA 633 3382875 7 ENTRE AVENIDA 4 Y 5 NO. EXT. 452 NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) 0013 - COLONIA CENTRO DE SALUD RURAL 002 - AGUA PRIETA MORELOS COLONIA MORELOS 633 3369056 DOMICILIO CONOCIDO NO. EXT. NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) CASA DE SALUD 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0009 - CABULLONA CABULLONA 999 9999999 UNICA CALLE PRINCIPAL NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84305) CASA DE SALUD EL 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0046 - EL RUSBAYO RUSBAYO 999 9999999 UNICA CALLE PRINCIPAL NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84306) CENTRO ANTIRRÁBICO VETERINARIO AGUA 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA SONORA 999 9999999 5 Y AVENIDA 17 NO. EXT. NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) HOSPITAL GENERAL, CARRETERA VIEJA A CANANEA KM. 7 NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA AGUA PRIETA 633 1222152 C.P. (84250) UNEME CAPA CENTRO NUEVA VIDA AGUA CALLE 42 NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , AVENIDA 8 Y 9, COL. LOS OLIVOS C.P. 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA 633 1216265 (84200) UNEME-ENFERMEDADES 38 ENTRE AVENIDA 8 Y AVENIDA 9 NO. EXT. SIN NÚMERO NO. -

The Baja California Peninsula, a Significant Source of Dust in Northwest Mexico

atmosphere Article The Baja California Peninsula, a Significant Source of Dust in Northwest Mexico Enrique Morales-Acuña 1 , Carlos R. Torres 2,* , Francisco Delgadillo-Hinojosa 3 , Jean R. Linero-Cueto 4, Eduardo Santamaría-del-Ángel 5 and Rubén Castro 6 1 Postgrado en Oceanografía Costera, Facultad de Ciencias Marinas, Instituto de Investigaciones Oceanológicas, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Carretera Tijuana-Ensenada, Zona Playitas, Ensenada 3917, Baja California, Mexico; [email protected] 2 Instituto de Investigaciones Oceanológicas, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Centro Nacional de Datos Oceanográficos, Carretera Tijuana-Ensenada, Zona Playitas, Ensenada 3917, Baja California, Mexico 3 Instituto de Investigaciones Oceanológicas, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Carretera Tijuana-Ensenada, Zona Playitas, Ensenada 3917, Baja California, Mexico; [email protected] 4 Facultad de Ingeniería, Universidad del Magdalena, Carrera 32 No. 22-08, Santa Marta, Magdalena 470004, Colombia; [email protected] 5 Facultad de Ciencias Marinas, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Carretera Tijuana-Ensenada, Zona Playitas, Ensenada 3917, Baja California, Mexico; [email protected] (E.S.-d.-Á.); [email protected] (R.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 26 August 2019; Accepted: 17 September 2019; Published: 26 September 2019 Abstract: Despite their impacts on ecosystems, climate, and human health, atmospheric emissions of mineral dust from deserts have been scarcely studied. This work estimated dust emission flux (E) between 1979 and 2014 from two desert regions in the Baja California Peninsula (BCP) using a modified dust parameterization scheme. Subsequently, we evaluated the processes controlling the variability of E at intra- and interannual scales. During the period 1979–2014 peak E were generally recorded in summer (San Felipe) and spring (Vizcaino), and the lowest emissions occurred in autumn (San Felipe) and winter (Vizcaíno). -

Tarifas VIGENTES 2021

CAMINOS Y PUENTES FEDERALES DE INGRESOS Y SERVICIOS CONEXOS RED FONADIN: TARIFAS-VIGENTES 2021 (CON IVA) - Cifras en pesos - CAMINOS Y PUENTES TRAMO QUE COBRA EN VIGOR A MOTOS AUTOS AUTOBUSES CAMIONES CASETAS PARTIR DE M A B2 B3 B4 C2 C3 C4 C5 C6 C7 C8 C9 EEA EEC 1 CUERNAVACA-ACAPULCO Ago 02 2021 271 543 883 883 883 879 879 879 1,154 1,154 1,285 1,285 1,285 272 441 CENTRAL DE ABASTOS CUERNAVACA-CENTRAL DE ABASTOS Ago 02 2021 4 9 14 14 14 13 13 13 19 19 23 23 23 5 7 AEROPUERTO CUERNAVACA-AEROPUERTO Ago 02 2021 7 14 27 27 27 26 26 26 33 33 35 35 35 7 13 AEROPUERTO AEROPUERTO-CUERNAVACA Ago 02 2021 7 14 27 27 27 26 26 26 33 33 35 35 35 7 13 XOCHITEPEC CUERNAVACA-XOCHITEPEC Ago 02 2021 13 26 33 33 33 32 32 32 38 38 41 41 41 13 16 XOCHITEPEC XOCHITEPEC-ALPUYECA Ago 02 2021 4 8 16 16 16 14 14 14 19 19 23 23 23 4 7 ING. FRANCISCO VELAZCO DURAN(D) CUERNAVACA-PUENTE DE IXTLA Ago 02 2021 40 80 137 137 137 137 137 137 171 171 188 188 188 40 69 ALPUYECA (I1) CUERNAVACA-ALPUYECA Ago 02 2021 28 56 96 96 96 95 95 95 118 118 133 133 133 28 48 ALPUYECA (I2) ALPUYECA-PUENTE DE IXTLA Ago 02 2021 12 25 32 32 32 31 31 31 39 39 41 41 41 13 16 PASO MORELOS (D) PUENTE DE IXTLA-CHILPANCINGO Ago 02 2021 84 169 351 351 351 348 348 348 457 457 507 507 507 85 174 PASO MORELOS (I1) PUENTE DE IXTLA-PASO MORELOS Ago 02 2021 33 66 141 141 141 140 140 140 182 182 167 167 167 33 70 PASO MORELOS (I2) PASO MORELOS-CHILPANCINGO Ago 02 2021 51 103 207 207 207 208 208 208 278 278 281 281 281 52 104 PALO BLANCO CHILPANCINGO-TIERRA COLORADA Ago 02 2021 78 156 203 203 203 203 -

Presidio Inspection Reports, 1791-1804

ARIZONA HISTORICAL SOCIETY 949 East Second Street Library & Archives Tucson, AZ 85719 (520) 617-1157 [email protected] MS 1202 Presidio Inspection Reports, 1791-1804 DESCRIPTION Photocopies of annual Presidio Inspection Reports for selected Sonoran (and one Chihuahuan) presidios, dated 1791, 1792, and 1800 to 1804, including Altar, Tucson, Santa Cruz, Tubac, Buenavista, Bavispe, Bacoachi, Frontera, and Monclova. The reports list officers, number of soldiers, and contain enlistment and service records. Some reports also include complete rosters and summaries of individual's financial accounts at the post. Also present are photocopies of service records for the officers of the Tucson Presidio between 1787 and 1799. The reports were copied from the Archivo General de Simancas, Secretaría de Guerra, Valladolid, Spain. 1 box, .25 linear ft. HISTORICAL NOTE According to historian Henry Dobyns, the Spanish colonization of its northern borderlands in New Spain occurred chiefly for defensive reasons. The military frontier advanced to protect the missionaries as they tried to convert Native Americans to Christianity. Posts were founded at Tubac and Altar in the aftermath of the Northern Pima Revolt in 1752. Later, protection of an overland route to Upper California was deemed necessary and the Tucson presidio was established in 1775. ACQUISITION The copies were donated by Homer Thiel in July 2001 and July 2002. ACCESS There are no restrictions on access to this collection. COPYRIGHT Requests for permission to publish material from this collection should be addressed to the Arizona Historical Society - Tucson, Archives Department. PROCESSING The finding aid was prepared by Kim Frontz, August 2001. ARRANGEMENT Chronological BOX AND FOLDER LIST Box 1 f. -

Avocado Studies in Mexico in 1938

California Avocado Association 1938 Yearbook 23: 67-85 Avocado Studies in Mexico in 1938 A. D. SHAMEL Principal Physiologist, Division of Fruit and Vegetable Crops and Diseases United States Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Plant Industry The Fuerte is the most important commercial avocado variety grown in California, since more than seventy-five per cent of the acreage and production is of that variety. This relatively high proportion is increasing because the Fuerte trees in southern California have survived low winter temperatures more successfully than most other commercial varieties. The Fuerte variety originated as a bud propagation of the parent Fuerte tree (fig. 1) that is located in the Le Blanc garden at Atlixco, state of Puebla, Mexico. The next most important commercial variety, Puebla, has been propagated in southern California from buds of a tree in the Vicente Pineda garden (fig. 2) that is located near the Le Blanc garden. The buds from the parent trees of both the Fuerte and Puebla were obtained at the same time, 1911, by Carl B. Schmidt of Mexico City, and sent to the West India Gardens at Altadena, California. The recent visit of about fifty members of the California Avocado Association and friends to Atlixco on April 17, 1938, was for the purpose of unveiling a memorial tablet at the site of the Fuerte tree and presenting medals to Alejandro Le Blanc, son of the man who planted the parent Fuerte tree, and to Carl B. Schmidt, who sent the buds to California. Appropriate congratulatory speeches were made by the Governor of the state of Puebla, the Secretary of the Mexican Department of Agriculture representatives of the U. -

America's Trade Corridor North America's Emerging Supply Chain and Distribution Network

America's Trade Corridor North America's Emerging Supply Chain and Distribution Network Calgary GDP o $98 Billion Callgary BRITISH ALBERTA MANITOBA COLUMBIA SASKATCHEWAN Vancouver GDP ¥ooVancouver $110 Billion Port of o Vancouover o o o MINNESOTA Seattle GDP Port of Seattle Spokane Tacomao o NORTH ¥o 90 $267 Billion o o $267 Billion ¥o WASHINGTOoN DAKOTA Port of 90 Seattle o MONTANA Helena 82 94 o Portland GDP ooPortlland 84 ¥ 90 $159 Billion Port of Portland SOUTH 90 DAKOTA OREGON Boiise IDAHO WYOMINGo o 84 11 15 25 IOWA 80 NEBRASKA Salt 5 Cheyenne Lake 80 Salt Lake City GDP oCity 80 $74 Billion Denver GDP Denver o Reno Aurora o NEVADA $170 Billion Aurora UTAH Colorado 70 Springs Sacramento GDP oSacramento COLORADO KANSAS $127 Billion Stockton San Francisco¥oOaklland San Francisco GDP o Port of oSan Jose $331 Billion $331 Billion Oakland Las Vegas GDP Fresno o $94 Billion Las San Jose GDP CALIFORNIA Vegas $160 Billion o ARIZONA OKLAHOMA Kingman Riverside GDP o 40 Flagstaff Albuquerque GDP Allbuquerque Oxnard GDP Lake o 40 $155 Billion Havasu $40 Billion $46 Billion Prescott Los Ciity NEW 17 Payson Show Low Los Angeles GDP Oxnard Angeles MEXICO o o Riverside Port of ¥ $860 Billion o o Los Angeles ¥o 10 Phoenix GDP Phoeniix-Mesa-Gllendalle Port of $207 Billion oo o San Long Beach Casa Grande Diiego 8 o *#oYuma BAJA San Luiis Tucson GDP Tucson 10 o San Diego GDP P..O..E.. o CALIFORNIA $4*#1 Billion $202 Billion o Lukeville 19 Dougllas ¥ Lukeville Sasabe Nogalles P.O.E. -

Redalyc.Murallas Y Fronteras: El Desplazamiento De La Relación Entre

Cuadernos de Antropología Social ISSN: 0327-3776 [email protected] Universidad de Buenos Aires Argentina Stephen, Lynn Murallas y Fronteras: El desplazamiento de la relación entre Estados Unidos - México y las comunidades trans-fronterizas Cuadernos de Antropología Social, núm. 33, enero-julio, 2011, pp. 7-38 Universidad de Buenos Aires Buenos Aires, Argentina Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=180921406001 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Cuadernos de Antropología Social Nº 33, pp. 7–38, 2011 © FFyL – UBA – ISSN 0327-3776 Murallas y Fronteras: El desplazamiento de la relación entre Estados Unidos – México y las comunidades trans-fronterizas Lynn Stephen* Resumen Por necesidad, este articulo incorpora una discusión de las comunidades transfronterizas con- temporáneas –comunidades repartidas en múltiples ubicaciones de los EE. UU. y México– en la historia de la relación entre México-EE. UU. durante los siglos XIX y XX. La flexibilidad de la frontera México-EE. UU. a través del tiempo y en las experiencias vividas por aquellos que la llevan a donde quieran metafóricamente, nos sugiere que en lugar de utilizar concep- tos como “el muro” para establecer limites y diferencias, seria mas útil concentrarnos en un concepto de fronteras múltiples. Argumentaré que el concepto de “transfronteras”, al incluir fronteras de colonialidad, etnia, raza, nación y región nos puede ayudar a iluminar las relaciones México-Estados Unidos a través del tiempo, y a comprender por qué es tan fuerte cultural y políticamente la idea del “muro” en los EE. -

Administracion Municipal 2018 - 2021

ADMINISTRACION MUNICIPAL 2018 - 2021 ACONCHI (Coalición PRI-VERDE-NUEVA ALIANZA) Presidente Municipal CELIA NARES LOERA Dirección Obregón y Pesqueira #132 Col. Centro, Ayuntamiento Aconchi, Sonora Tel. Oficina 01 623 233-01-39 233-01-55 Tel. Particular Celular Email Presidenta DIF C. DAMIAN EFRAIN AGUIRRE DEGOLLADO Dirección DIF Obregón y Pesqueira #132 Col. Centro, Aconchi, Sonora Tel. DIF 01 623 233-01-39 ext 112 01 (623) 23 30 001 Celular Email [email protected] Cumpleaños [email protected] Director DIF SRA. Evarista Soto Duron Celular Email [email protected] Email oficial ADMINISTRACION MUNICIPAL 2018 - 2021 AGUA PRIETA (Coalición MORENA – PT – ENCUENTRO SOCIAL) Presidente Municipal ING. JESÚS ALFONSO MONTAÑO DURAZO Dirección Calle 6 y 7 e/Ave. 16 y 17 Col. Centro CP Ayuntamiento 84200, Agua Prieta, Sonora Tel. Oficina 01 633 338-94-80 ext. 2 333-03-80 Tel. Particular Celular Srio. Particular Mtro. Juan Encinas Email: [email protected] Presidenta DIF SRA. MARIA DEL CARMEN BERNAL LEÓN DE MONTAÑO Dirección DIF Calle 4 Ave. 9 y 10 Col. Centro CP 84200, Agua Prieta, Sonora Tel. DIF 01 633 338-20-24 338-27-31 338-42-73 Celular Email cumpleaños Director DIF MTRA. AURORA SOLANO GRANADOS Celular Email [email protected] Cumpleaños ADMINISTRACION MUNICIPAL 2018 - 2021 ALAMOS (Coalición PRI-VERDE-NUEVA ALIANZA) Presidente Municipal VÍCTOR MANUEL BALDERRAMA CÁRDENAS Dirección Calle Juárez s/n Col. Centro, Álamos, Sonora Ayuntamiento Tel. Oficina 01 647 428-02-09 647 105-49-16 Tel. Particular Celular Email Presidenta DIF SRA. ANA REBECA BARRIGA GRAJEDA DE BALDERRAMA Dirección DIF Madero s/n Col. -

A Distributional Survey of the Birds of Sonora, Mexico

52 A. J. van Rossem Occ. Papers Order FALCONIFORMES Birds of PreY Family Cathartidae American Vultures Coragyps atratus (Bechstein) Black Vulture Vultur atratus Bechstein, in Latham, Allgem. Ueb., Vögel, 1, 1793, Anh., 655 (Florida). Coragyps atratus atratus van Rossem, 1931c, 242 (Guaymas; Saric; Pesqueira: Obregon; Tesia); 1934d, 428 (Oposura). — Bent, 1937, 43, in text (Guaymas: Tonichi). — Abbott, 1941, 417 (Guaymas). — Huey, 1942, 363 (boundary at Quito vaquita) . Cathartista atrata Belding, 1883, 344 (Guaymas). — Salvin and Godman, 1901. 133 (Guaymas). Common, locally abundant, resident of Lower Sonoran and Tropical zones almost throughout the State, except that there are no records as yet from the deserts west of longitude 113°, nor from any of the islands. Concentration is most likely to occur in the vicinity of towns and ranches. A rather rapid extension of range to the northward seems to have taken place within a relatively few years for the species was not noted by earlier observers anywhere north of the limits of the Tropical zone (Guaymas and Oposura). It is now common nearly everywhere, a few modern records being Nogales and Rancho La Arizona southward to Agiabampo, with distribution almost continuous and with numbers rapidly increasing southerly, May and June, 1937 (van Rossem notes); Pilares, in the north east, June 23, 1935 (Univ. Mich.); Altar, in the northwest, February 2, 1932 (Phillips notes); Magdalena, May, 1925 (Dawson notes; [not noted in that locality by Evermann and Jenkins in July, 1887]). The highest altitudes where observed to date are Rancho La Arizona, 3200 feet; Nogales, 3850 feet; Rancho Santa Bárbara, 5000 feet, the last at the lower fringe of the Transition zone. -

Artistic Geography and the Northern Jesuit Missions of New Spain

Artistic Geography and the Northern Jesuit Missions of New Spain By Clara Bargellini Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México [email protected] (working paper, not be reproduced without the author’s permission) George Kubler´s seminal thoughts on artistic geography came out of his involvement with the art and architecture of the Hispanic New World. This paper examines a group of 17th and 18th century Jesuit missions in northern Mexico in order to expand our understanding of New World artistic geography, and also to explore the history of some geographic notions and their place in art historical discussions. Whereas Kubler was concerned with the transmission of styles, my interest here will be the movement of specific objects and individuals within a particular historical configuration. This will involve, of course, considerations about patronage and institutions, with some references to iconography, all of which ultimately has implications for the transmission of styles, as Kubler would no doubt have recognized. The missions in question were established in the first half of the 17th century by the Jesuits in the northern Tepehuan and Southeastern Tarahumara region, and were held by the Society until its 1767 expulsion from New Spain. From their arrival in 1572 the Jesuits focused on ministry among the native population of New Spain. Almost at once they began missionary activity among the indigenous populations in places near Mexico City. By 1580 they were established at Tepotzotlán learning native languages. In 1589 the Jesuits were among the legendary chichimecas at San Luis de la Paz, and two years later they were in Sinaloa, where they established an extraordinary system of missions about which we now have only documents and very sparse remains.