Labour Struggles in the Canadian Communication Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TWU Wrestles with Telus in Court

Union optimistic after VoIP hearings By Sid Shniad, TWU Research Director The TWU urged the have phone conversations companies be regulated in the Transmitter article by Rod) the effects of deregulation and Canadian Radio-television over the Internet, should be same way as VoIP provided that telephone companies are were taking the TWU’s call to and Telecommunications regulated in the same way as by telephone companies, and using VoIP to restructure their regulate all of the players in Commission (CRTC) to fully wireline service, TWU the CRTC shouldn’t let any operations and finances to the sector seriously. It is too regulate Voice-over Internet president Rod Hiebert, lawyer company offer VoIP until it is avoid regulatory oversight. early to tell what this will Protocol (VoIP), in a three- Jim Aldridge and I told the capable of providing During the hearing, it ultimately mean, but the signs day hearing held late CRTC. The TWU also emergency services like 911. became clear that at least are good. After years of September in Ottawa. recommended that VoIP The TWU pointed out (as some of the CRTC panel participating in proceedings Vo IP, which allows users to service provided by cable detailed in a recent members are concerned about (see TWU urges -- page 5) October 2004 XXVI 2 TWU wrestles with Telus in court Last January the deal was Then, just a couple of accusations of bias, but unacceptable, and appealed the Board in Letter Decision sealed. It was good news. weeks later, the company flip- instead dismissed them as for a Judicial Review in the 1004. -

2003 Annual Report

Labour Community Services of Toronto 2003 Annual Report Labour Community Services is a project of the Toronto and York Region Labour Council in partnership with the United Way of Greater Toronto Message from the President of the Board of Labour Community Services It was the best of times, it was the worst of times… The opening line from Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities could easily describe the reality of Toronto today. With dramatic changes of politics at Queen’s Park and City Hall, there is a new sense of optimism in the air. Finally, we can start to rebuild our city, its schools, and its social infrastructure that has been crumbling over the last number of years. Yet at the same time poverty, the lack of affordable housing, and the rise of precarious employment strip that optimism away for too many in our community. Family incomes have plummeted and inequality has increased. People of colour, newcomers to Canada and residents of Toronto’s inner suburbs are particularly hard hit. These challenges were front and centre in two recent reports. The United Way’s Poverty by Postal Code: The Geography of Neighbourhood Poverty, 1981-2001 charts the dramatic rise and intensification in the number of high-poverty neighbourhoods. The report points to the acute crisis affecting one in five Toronto families. The Community Social Planning Council’s Falling Fortunes: A Report on the Status of Young Families in Toronto makes the clear connection between diminished job opportunities and the growth of poverty. Both call out for action and increased resources. -

What Matters to You Matters to Us 2013 ANNUAL REPORT

what matters to you matters to us 2013 ANNUAL REPORT Our products and services Wireless TELUS provides Clear & Simple® prepaid and postpaid voice and data solutions to 7.8 million customers on world-class nationwide wireless networks. Leading networks and devices: Total coverage of 99% of Canadians over a coast-to-coast 4G network, including 4G LTE and HSPA+, as well as CDMA network technology. We offer leading-edge smartphones, tablets, mobile Internet keys, mobile Wi-Fi devices and machine- to-machine (M2M) devices Data and voice: Fast web browsing, social networking, messaging (text, picture and video), the latest mobile applications including OptikTM on the go, M2M connectivity, clear and reliable voice services, push-to-talk solutions including TELUS LinkTM service, and international roaming to more than 200 countries Wireline In British Columbia, Alberta and Eastern Quebec, TELUS is the established full-service local exchange carrier, offering a wide range of telecommunications products to consumers, including residential phone, Internet access, and television and entertainment services. Nationally, we provide telecommunications and IT solutions for small to large businesses, including IP, voice, video, data and managed solutions, as well as contact centre outsourcing solutions for domestic and international businesses. Voice: Reliable home phone service with long distance and Hosting, managed IT, security and cloud-based services: advanced calling features Comprehensive cybersecurity solutions and ongoing assured 1/2 INCH TRIMMED -

Evolving Our Business Delivering on Our Strategy

evolving our business delivering on our strategy ® TELUS Communications Inc. • annual report 2002 table of contents forward-looking statements inside front cover management’s discussion and analysis 1 consolidated statistics 22 management’s report 23 auditors’ report 24 consolidated financial statements 25 directors and officers 51 investor information 52 forward-looking statements Management’s discussion and analysis contains statements about expected future events and financial and operating results that are forward-looking and subject to risks and uncertainties. TELUS Communications Inc.’s actual results, performance or achievement could differ materially from those expressed or implied by such statements. Such statements are qualified in their entirety by the inherent risks and uncertainties surrounding future expectations and may not reflect the potential impact of any future acquisitions, mergers or divestitures. Factors that could cause actual results to differ materially include but are not limited to: general business and economic conditions in TELUS Communications Inc.’s service territories across Canada and future demand for services; competition in wireline and wireless services, including voice, data and Internet services and within the Canadian telecommunications industry generally; re-emergence from receivership of newly restructured competitors; levels of capital expenditures; success of operational and capital efficiency programs including maintenance of customer service levels; success of integrating acquisitions; network -

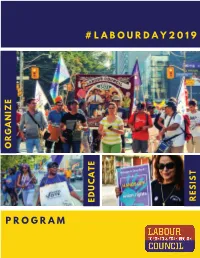

Labour Day Program 2019

PROGRAM ORGANIZE #LABOURDAY2019 EDUCATE RESIST HAPPY LABOUR DAY! On Monday, September 2, over 20,000 union members will take to the streets in the annual Labour Day Parade. The 2019 theme “Organize, Educate, Resist!” was chosen to bolster worker solidarity in the face of the Ford government’s austerity agenda and to ready unions for the fights ahead. The first fifteen months of this Ford government have confirmed what we predicted: that the Conservatives would wreak havoc across the entire province, stripping workers’ rights, cutting programs and undermining the integrity of our education system and health services. Their record shows us why Canadians cannot risk having the Conservatives take power at the federal level. Our unions are committed to fighting against these regressive measures in every way possible. We are committed to building inclusive workplaces and communities, and challenging the politics of hate. Unions in greater Toronto have been working together for justice since 1871, and we are proud of what our members do every day to benefit all Canadians. This year’s parade will include workers who are organizing in sectors driven by the digital economy, including Foodora delivery workers and Uber drivers. The parade’s lead union is International Union of Operating Engineers Local 793, celebrating its 100th anniversary. The Toronto Labour Day parade has been held by the Labour Council annually since 1872. Labour Day has been officially recognized on the first Monday in September since 1894. The Toronto & York Region Labour Council is a central labourr bodybody that combines the strength of local unions representing 200,000 women and menen whowho work in every sector of the economy. -

Phase One Environmental Site Assessment, Redevelopment Parcel, Northeast Part of Merivale Mall, 1642 Merivale Road, Ottawa, Ontario

REPORT Phase One Environmental Site Assessment, Redevelopment Parcel, Northeast Part of Merivale Mall, 1642 Merivale Road, Ottawa, Ontario Submitted to: First Capital Asset Management LP 85 Hanna Avenue, Suite 400 Toronto, Ontario M6K 3S3 Submitted by: Golder Associates Ltd. 100 Scotia Court, Whitby, Ontario, L1N 8Y6, Canada +1 905 723 2727 19123353 September 2019 September 2019 19123353 Distribution List 1 copy (.pdf) - First Capital Asset Management LP 1 copy - Golder Associates Ltd. i September 2019 19123353 Table of Contents 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 2.1 Phase One Property Information.......................................................................................................... 1 3.0 SCOPE OF INVESTIGATION ......................................................................................................................... 2 4.0 RECORDS REVIEW ....................................................................................................................................... 2 4.1 General ................................................................................................................................................. 2 4.1.1 Phase One Study Area Determination ........................................................................................... -

ANNUAL REPORT Labour’S Voice in the Community

ANNUAL REPORT Labour’s Voice in the Community Labour Community Services is a project of the Toronto and York Region Labour Council in partnership with the United Way of Greater Toronto usw 8300 What’s Inside LCS Mission Statement Page 3 LCS Board Members Page 4 Greetings from John Cartwright, President of the Board of Directors Page 5 Message from Frances Lankin, President and CEO of UWGT Page 6 Message from Faduma Mohamed, LCS Executive Director Page 7 Highlights of 2006 Page 8 2006/2007 Union Counsellor Graduates Page 12 2006 United Way Volunteer Recognition Page 14 2006 Union Honour Roll Page 15 History of the United Way and Labour Page 17 Tropicana Community Services Page 19 Labour Education Centre Page 20 A Million Reasons to Raise the Minimum Wage Now Page 21 Photos from Last Year’s Annual Meeting Page 22 Lifeline Foundation Page 23 usw 8300 MISSION STATEMENT of Labour Community Services To create a deep and lasting social solidarity between labour and community to achieve a just and equitable society for all. Objectives • Organize workers and families in their communities and organizations to improve quality of life through education, advocacy for social justice and provision of needs (social services) • Establish healthy communities through union solidarity • Build a bridge to improve the lives of people in communities who are also union members. In doing this we will establish an environment of community unionism • Work toward a more just and equitable society for workers and their families Page 3 of 23 Labour Community Services -

2002 Annual Report 353 and the International Association of Machinists, Lodge 235, All of the Toronto Star

Message from the President of the Board of Labour Community Services Poverty, the lack of affordable housing, cuts to social services – clearly the needs in Toronto are greater than ever. Family incomes have plummeted and inequality has increased. Homelessness remains an urgent problem, seniors are struggling, and many working families have difficulty making ends meet. These challenges were front and centre at the June 2003 Toronto City Summit. The City Summit Alliance was formed to address the challenges identified by a wide spectrum of groups and individual activists: finance, infrastructure, education, immigration and the underlying health of our regional economy. This coalition of 45 civic leaders, including labour, has issued a bold call to action, Enough Talk: An Action Plan for the Toronto Region. The Action Plan will surely be used as a test to all politicians that claim to represent our city, whether they serve at the municipal, provincial or federal level. We need every one of them to sign on to a commitment to a fair deal for Canada’s largest urban centre. Labour Community Services also plays a vital role in meeting these challenges, both through its education programs and community services, as well as its partnership with the United Way. LCS volunteers and staff had a very active year in 2002. Labour campaign volunteers actively encouraged union locals and members to get involved during the 2002 United Way campaign. It is not easy to ask working people to give generously when they are struggling to defend their own jobs or their incomes. During the year, both our city and provincial employees were forced out on strike. -

01 Telus2001 OC

we are 2001 annual report corporate profile TELUS Corporation is one of Canada’s leading providers of data, Internet Protocol (IP), voice and wireless communications services. We provide and integrate a full range of communications products and services that connect Canadians to the world. Our strategy is to unleash the power of the Internet to deliver the best solutions to Canadians at home, in the workplace and on the move. In 2001, we generated $7.2 billion in revenues and further strengthened our national position by successfully integrating Clearnet and rebranding as TELUS Mobility, purchasing several small data and Internet companies and completing our cross-Canada IP backbone network. future friendly table of contents i TELUS at a glance 26 frequently asked questions 1 financial and operating highlights 31 community investment 2 why invest in TELUS 32 forward-looking statements 3 2002 targets 33 financial and operating statistics 4 letter to shareholders 38 management discussion and analysis look for these images to see examples strategic imperatives 55 consolidated financial statements of future friendly TELUS solutions 10 providing integrated solutions 84 executive leadership team & 13 building national capabilities board of directors 16 partnering, acquiring 85 glossary and divesting 88 investor information 19 focusing on data, IP and wireless growth ibc national infrastructure map 22 going to market as one team 24 investing in internal capabilities Forward-Looking Disclaimer This report contains statements about expected future events and financial and operating results of TELUS that are forward-looking and subject to risks and uncertainties. Accordingly, these statements are qualified in their entirety by the inherent risks and uncertainties surrounding future expectations. -

Leading the World When the World Needs Us Most

Leading the world when the world needs us most ANNUAL REPORT 2020 We are leading the world TELUS is a dynamic, world-leading communications 1–9 technology company with $16 billion in annual revenue Corporate overview and 16 million customer connections spanning wireless, data, IP, voice, television, entertainment, video and Supporting our stakeholders through an unprecedented year, results and highlights security. We leverage our global-leading technology from 2020, and our 2021 targets and compassion to enable remarkable human outcomes. Our long-standing commitment to putting our customers first fuels every aspect of our business, 10–15 making us a distinct leader in customer service CEO letter to investors excellence and loyalty. TELUS Health is Canada’s Keeping our stakeholders connected to leader in digital health technology, TELUS Agriculture what matters most through our leadership in social capitalism provides innovative digital solutions throughout the agriculture value chain and TELUS International is a leading digital customer experience innovator 16–17 that delivers next-generation AI and content Our social purpose at a glance management solutions for global brands. Leveraging technology to enable remarkable human outcomes Driven by our passionate social purpose to connect all citizens for good, our deeply meaningful and 18 –21 enduring philosophy to give where we live has inspired Operations at a glance TELUS, our team members and retirees to contribute Reviewing our wireless and wireline more than $820 million and 1.6 million days of operations service since 2000. This unprecedented generosity and unparalleled volunteerism have made TELUS the most giving company in the world. 22– 29 Leadership Our Executive Team, questions and answers, Many photos within this report were taken Board of Directors and corporate governance prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. -

Celebrating 60 Years: the ACTRA STORY This Special Issue Of

SPECIAL 60TH EDITION 01 C Celebrating 60 years: THE ACTRA STORY This special issue of InterACTRA celebrates ACTRA’s 60th Anniversary – 60 years of great performances, 60 years of fighting for Canadian culture, 4.67 and 60 years of advances in protecting performers. From a handful of brave and determined $ 0256698 58036 radio performers in the ‘40s to a strong 21,000-member union today, this is our story. ALLIANCE ATLANTIS PROUDLY CONGRATULATES ON 60 YEARS OF AWARD-WINNING PERFORMANCES “Alliance Atlantis” and the stylized “A” design are trademarks of Alliance Atlantis Communications Inc.AllAtlantis Communications Alliance Rights Reserved. trademarks of “A” design are Atlantis” and the stylized “Alliance 1943-2003 • actra • celebrating 60 years 1 Celebrating 60 years of working together to protect and promote Canadian talent 401-366 Adelaide St.W., Toronto, ON M5V 1R9 Ph: 416.979.7907 / 1.800.567.9974 • F: 416.979.9273 E: [email protected] • W: www.wgc.ca 2 celebrating 60 years • actra • 1943-2003 SPECIAL 60th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 2003 VOLUME 9, ISSUE 3 InterACTRA is the official publication of ACTRA (Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists), a Canadian union of performers affiliated to the Canadian Labour Congress and the International Federation of Actors. ACTRA is a member of CALM (Canadian Association of Labour Media). InterACTRA is free of charge to all ACTRA Members. EDITOR: Dan MacDonald EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE: Thor Bishopric, Stephen Waddell, Brian Gromoff, David Macniven, Kim Hume, Joanne Deer CONTRIBUTERS: Steve -

37787 in the Supreme Court of Canada

SCC Court File No: 37787 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF APPEAL) BETWEEN:BETWEEN : CANADA POST CORPORATION APPELLANT (Respondent) - and —– CANADIAN UNION OF POSTAL WORKERS RESPONDENT (Appellant) (Style of cause continues inside cover page) FACTUM OF THE INTERVENER, FETCO INC. (FEDERALLY REGULATED EMPLOYERS - TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATIONS) (Pursuant to Rule 42 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of CanadaCanada)) FASKEN MARTINEAU DuMOULIN LLP FASKEN MARTINEAU DuMOULIN LLP Bay Adelaide Centre 55 Metcalfe Street 333 Bay Street, Suite 2400 Suite 13001300 Toronto, ON M5H 2T6 Ottawa, Ontario KIPK1P 6L5 Christopher D. Pigott - LSO No. 59036A Sophie Arseneault - LSO No. 67409U Rachel Younan - LSO No. 68955N Telephone : 416 865 5475 Telephone :2 613 696 6904 Facsimile :2 416 364 7813 Facsimile : 613 230 6423 Email : [email protected] Email :2 [email protected] Counsel foforr the Intervener, Ottawa Agent for the Intervener, FETCO Inc. (Federally Regulated FETCO Inc. (Federally Regulated Employers Employers - Transportation and - Transportation and Communications) Communications) - andand- – ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA, DHL EXPRESS (CANADA), LTD., FEDERAL EXPRESS CANADA CORPORACORPORATION,TION, PUROLATOR INC., TFI INTERNATIONAL INC. and UNITED PARCEL SERVICE CANADA LTD., FETCO INC. (FEDERALLY REGULATED EMPLOYERS - TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATIONS), CANADIAN UNION OF PUBLIC EMPLOYEES and PROFESSIONAL INSTITUTE OF THE PUBLIC SERVICE OF CANADCANADA,A, WORKERS’WORKERS’ HEALTH AND SAFETY LEGAL CLINIC, ROGERS