Seth Feldman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I'm Special I I'm Special

!^W.'UJtf"-V^j! _j my I'm Special i I'm special. In all the world there's nobody like me. Since the beginning of time, there has never been another person like me. Nobody has my smile. Nobody has my eyes, my nose, my hair, my voice. I'm special. No one can be found who has my handwriting. Nobody anywhere has my tastes - for food or music or art. no one sees things just as I do. In all of time there's been no one who laughs like me, no one who cries like me. And what makes me laugh and cry will never provoke identical laughter and tears from anybody else, ever. No one reacts to any situation just as I would react. I'm special. I'm the only one in all of creation who has my set of abilities. Oh, there will always be somebody who is better at one of the things I'm good at, but no one in the universe can reach the quality of my com bination of talents, ideas, abilities and feelings. Like a room full of musical instruments, some may excel alone, but none can match the symphony of sound when all are played together. I'm a symphony. Through all of eternity no one will ever look, talk, walk, think or do like me. I'm special. I'm rare. And in rarity there is great value. Because of my great rare value, I need not attempt to imitate others. I willl accept - yes, celebrate - my differences. -

Exhibition Place Master Plan – Phase 1 Proposals Report

Acknowledgments The site of Exhibition Place has had a long tradition as a gathering place. Given its location on the water, these lands would have attracted Indigenous populations before recorded history. We acknowledge that the land occupied by Exhibition Place is the traditional territory of many nations including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat peoples and is now home to many diverse First Nations, Inuit and Metis peoples. We also acknowledge that Toronto is covered by Treaty 13 with the Mississaugas of the Credit, and the Williams Treaties signed with multiple Mississaugas and Chippewa bands. Figure 1. Moccasin Identifier engraving at Toronto Trillium Park The study team would like to thank City Planning Division Study Team Exhibition Place Lynda Macdonald, Director Don Boyle, Chief Executive Officer Nasim Adab Gilles Bouchard Tamara Anson-Cartwright Catherine de Nobriga Juliana Azem Ribeiro de Almeida Mark Goss Bryan Bowen Hardat Persaud David Brutto Tony Porter Brent Fairbairn Laura Purdy Christian Giles Debbie Sanderson Kevin Lee Kelvin Seow Liz McFarland Svetlana Lavrentieva Board of Governors Melanie Melnyk Tenants, Clients and Operators Dan Nicholson James Parakh David Stonehouse Brad Sunderland Nigel Tahair Alison Torrie-Lapaire 4 - PHASE 1 PROPOSALS REPORT FOR EXHIBITION PLACE Local Advisory Committee Technical Advisory Committee Bathurst Quay Neighbourhood Association Michelle Berquist - Transportation Planning The Bentway Swinzle Chauhan – Transportation Services -

Endless Dark Swimmer Marilyn Bell Recalls Historic Lake Ontario Crossing

New Paltz Times JanuaryJune 2314,, 20122014 •• 1 Personally speaking Endless dark Swimmer Marilyn Bell recalls historic Lake Ontario crossing by Mike Townshend she said. “He was one of the first peo- ple in the swimming world to say, ‘Hey, N THE MORNING, usually at we can make a difference here’.” about 6 a.m., Marilyn Di Lascio Ryder worked out a special deal with hits the pool at Woodland Pond her parents. Marilyn worked in the of- Iin New Paltz with her friends. The fice at the swim club’s pool in exchange room’s high wooden ceilings look a bit for continued lessons. “It was really a like a church -- a metaphor the 76-year- live-saving gesture to me.” old swimmer enjoys. She started training in hopes of mak- The room is her chapel, she says. ing the 1952 Olympic Games in Fin- Even after her brief but epoch-making land. She tried out, but the Olympics professional swimming career, and de- weren’t in the cards for her. At age 14, spite a degenerative back condition, she’d turned professional. She swam in water still holds magic for her. It’s still a 3-mile, professional women’s race on a lot like her first love. Lake Ontario. Those early pro races re- If you don’t know her story -- as treaded her old pattern -- placing third many Americans outside of hardcore or fourth -- but she was still pleased. swimmers do not -- Marilyn Bell Di Las- “The first year, I placed fourth. I was cio comes across as a nice old lady -- thrilled because I’d won $300, which charming, polite and quick with a joke. -

Celebrating 27 Years. “1994-2021” 1 U | MESSAGE

ONTARIO SPORTS HALL OF FAME | Celebrating 27 Years. “1994-2021” 1 u | MESSAGE A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT… 2020 was a year of tremendous upheaval for our province, testing the patience and endurance of our communities as we managed through the covid-19 crisis. The priority for all of us was to focus on mitigating the spread of this virus and keeping our communities safe. To that end, we elected to reschedule our annual celebration one year out at a new venue, the John Bassett Theatre in order to recognize our inductees and special award recipients. Our annual induction ceremony and awards gala is in its’ 27th year and I offer my personal and profound thanks for your past support for our annual celebration and related community activities. This year’s OSHOF Gala will present another stellar “Class of 2021” inductee lineup including an outstanding selection of special award recipients. Whether you choose to come on board as a major partner, as a corporate sponsor or with the purchase of individual tickets for you and your guests, your participation provides invaluable support enabling us to showcase and appreciate our most recognized sports athletes, community leaders and volunteer citizens. Of course, you can expect to indulge in a fabulous evening of tasty hors d’oeuvres, cocktails and unforgettable entertainment and many opportunities to bid on selected treasures in the live auction and participate in our 50-50 raffle. It’s a night of networking with your sporting heroes, business, community and philanthropic leaders, not to mention the athletes themselves. To our board of directors and volunteers who donate their time, talent and creativity, I extend my appreciation to them all! We must rely upon your generosity to sustain our celebration, education and awareness of Ontario sporting accomplishments to our citizens and communities across Ontario. -

The Life and Times of CAAWS

The Life and Times of CAAWS Badminton player Dorothy Walton, the first Canadian winner of the prestigious All England championship in 1939 and chosen one of the six best women athletes of the L huteuretracel;biztoriquc& UAWS (Association canadienne half century. pour hvancement &S fcmmes hns ks sports et llactivitC Figure skaters Barbara Ann Scott, winner of two world p&sique), une associationfin&+ m 1981 pour addresser &S championships and an Olympic title in the 1940s; Karen Magnussen, the star of the 1970s, with gold, silver, and bronze from three world championships to go with her Olympicsilver; the feistyworldchampion Isabelle Brasseur, Girh 'and women ? port has been characterized skating through pain to an Olympic bronze medal in by low hveh ofparticipation; absence fFom 1994. Marathon swimmers Marilyn Bell, the first person to hadership positions; inequitabh deliuery rystems; swim Lake Ontario, in 1954, and the youngest person to minimal research; and scant coverage in the media. swim the English Channel one year later; Cindy Nicholas, who in 1976 was the women's world marathon swimming champion; and Vicky Keith, who has swum across each of probhes & sow-repriscntations dcs femmes hns tow &S the Great Lakes. domaines sportif;. Cet artick hnne aux hctrices un aperp Alpine skiers Lucile Wheeler, in the 1950s, with Olym- &S objecti$ et du travail & UA WS. pic bronze and, at the world championships, two gold and a silver; in 1960, Anne Heggtveit, Olympic gold and The roots of the Canadian Association for the Advance- double world championship gold; Nancy Greene, gold ment ofwomen and Sport and Physical Activity (CAAWS) and silver at the 1968 Olympic Games and twice World reach deep, far deeper than most people realize. -

Davince Tools Generated PDF File

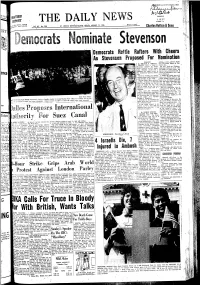

... ~ " CW~ANY i.l:,::rt~ jI\J d..J.J..... L~J:~~ , . ~)\1~f~~rb WEATlIER 1'lmSEN'rS LIS' Z T REPORT THE DAIL'Y NEWS al'ailable at , ;l1<\\I'N'~, cl~~rln!C Vor. 63. No. 208 ST. JOHN'S, NEWFOUNDLAND, FRIDAY, AUGUST 17, 1956 (Price 5_cents) lIi~h today 63. ____ ~ __________ --__ ----__ ~ r--~~------------------~~-- Charles Hutten &Sons • omlna 'e evenson . ' Ii " , Democrats Rattle Rafters With , Cheers. Steven!o,n Proposed For" Nonlination lIUJ.I,ETI:-.' mclange of cireui sideshow, Mardi lIy DOUGLAS II. COR:,\,EI.I. Gras and Times Square on New CHICAGO (AI') - Adlai IL .Ycar's Bvc. ., Stevenson capturcd the Dcmu.' The Ncw York and' Oklahoma cratic pre sid c n t i a I nomin,' delegations tolidly sat it out. ':'hey ation Thursday night with a: still clung to a futile, forlorn 'ope smashing fim ballot victory at: that by some miraculous turn of the Democratic 'national com'cn·' cvents thc nomination still I.ight tion.· i go to Harriman, 'Down to stunning but entircly i A handful of favorite son cadi· expccted defeat went Governor AI'. I! dales-stale leaders whep b, Am, ercll Harriman of New York, erican political tradition, g:! the Fur thc former Illinois gOl'ernor 'I honor of a first·ballot nomination ran like a champion, oUl front and Irom tllCir home delegations-al~o true to form all the way, He led: wcre put beforc thc 1.312 dcle· Irom the instant thc first state! ~atcs whu command I'otes 111 the laid it~ ballots on the Hne and presidcnti:tl balloting, Harriman ncvcr came rlosc to a' But thc:r candidacies wcre ov· ehallcnge, . -

Download This Page As A

Historica Canada Education Portal Leadership and Moving Mountains Overview This lesson plan is based on viewing the Footprint videos for Teeder Kennedy, Wayne Gretzky, Maurice Richard, Marilyn Bell, Terry Fox, and Larry Walker. Whether carrying a puck over the ice, slicing through water, crossing continents or excelling at America’s pastime (baseball), these athletes are leaders in their respective sports. But what makes them icons of leadership is just as much a matter of what they did beyond the sports arena to change the way we look at ourselves as Canadians. Aims To increase student awareness of Canadian athletes as leaders and agents of change; to learn how they have demonstrated their leadership on the national and international arenas; to understand the challenges each of these Canadians faced in pursing their goals; to analyse how the Canadian public accepts or rejects the inevitable flaws of its athletic ambassadors; and, to question accepted notions that associate certain physical character traits with leadership potential. Background The roots of athletic leadership may exist before birth, but it could be argued that circumstances, rather than innate ability, determine leadership potential. Teeder Kennedy's father was killed in a hunting accident one month before his son was born, initiating a series of events that would lead Teeder Kennedy to worship the blue and white jersey of the Toronto Maple Leafs throughout his life. As Kennedy's career evolved, Toronto's fans would return this affection. Maurice Richard emerged from the tough streets of French-Canadian Montreal to hoist the hopes and dreams of the Québécois nation on his shoulders. -

This Marks the Connection of Ontario's Section of the Great Trail of Canada in Honour of Canada's 150Th Anniversary of Confe

The Great Trail in Ontario Le Grand Sentier au Ontario This marks the connection of Ontario’s section of The Great Trail of Canada in honour of Canada’s 150th anniversary Ceci marque le raccordement du Grand Sentier à travers l’Ontario du Grand Sentier pour le 150e anniversaire de la of Confederation in 2017. Confédération canadienne en 2017. À partir d’où vous êtes, vous pouvez entreprendre l’un des voyages les plus beaux et les plus diversifiés du monde. From where you are standing, you can embark upon one of the most magnificent and diverse journeys in the world. Que vous vous dirigiez vers l’est, l’ouest, le nord ou le sud, Le Grand Sentier du Canada—créé par le sentier Whether heading east, west, north or south, The Great Trail—created by Trans Canada Trail (TCT) and its partners— Transcanadien (STC) et ses partenaires—vous offre ses multiples beautés naturelles ainsi que la riche histoire et offers all the natural beauty, rich history and enduring spirit of our land and its peoples. l’esprit qui perdure de notre pays et des gens qui l’habitent. Launched in 1992, just after Canada’s 125th anniversary of Confederation The Great Trail was conceived by a group of Lancé en 1992, juste après le 125e anniversaire de la Confédération du Canada, Le Grand Sentier a été conçu, par un visionary and patriotic individuals as a means to connect Canadians from coast to coast to coast. groupe de visionnaires et de patriotes, comme le moyen de relier les Canadiens d’un océan aux deux autres. -

Toronto Telegram Negatives: Subjects

Toronto Telegram fonds Inventory#433 Page 1 Toronto Telegram Negatives: Subjects CALL NUMBER FILE LIST 1974-002/001 A&A Record and Book Shop 24/07/71 A&P 13/07/64 - 19/01/71 A&W Drive Ins 24/06/69 Abbey Tavern Singers 16/01/67 - 11/10/67 Xref: St. Pauls R.C. Church 30/10/67 Aberfoyle, Ont. -- /04/64 Abortion Demonstration Xref: Women's Liberation 10/05/71 Abortion Laws Protest 22/04/70 Abortion 09/01/71 Abortion Law Panel 01/02/71 Abortion March 08/05/71 Academy of Dentistry 16/09/70 Academy of Medicine 14/11/67 - 08/04/70 Academy of Theatre Arts 07/10/64 Accident (O.S.) 24/08/49 Accident 16/04/62 - 04/02/65 1974-002/002 Accident -continued- -- /02/65 - -- /07/66 Xref: Lawrence Ave. 20/10/65 no neg. card only 18/01/66 no neg. card only 15/06/66 1974-002/003 Accident -continued- 19/08/66 - -- /08/69 no neg. card only 27/06/66 no neg. card only 13/09/66 no neg. card only 16/03/67 1974-002/004 Accident -continued- -- /09/69 - 31/08/71 Xref: Weather - Ice storm 23/02/71 Accidental Shooting 22/05/63 Accordion Championships 16/04/66 ACME Screw and Gear 20/01/71 - 26/01/71 ACME Screw and Tool Co. 16/02/68 Acres Ltd. 06/07/65 - 22/05/69 Actinolite, Ont. 07/02/59 Action '68 10/06/68 Action File 28/06/71 Actra 01/10/65 1974-002/004 Adams and Yves Gallery 28/03/68 Toronto Telegram fonds Inventory#433 Page 2 Toronto Telegram Negatives: Subjects CALL NUMBER FILE LIST Addiction Research Foundation -no date- Addison Cadillac 18/09/67 - 15/10/70 Adjala Township, Ont. -

House of Commons Debates

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 140 Ï NUMBER 100 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 38th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Tuesday, May 17, 2005 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 6043 HOUSE OF COMMONS Tuesday, May 17, 2005 The House met at 10 a.m. This act proposes to create mandatory minimum sentences for carrying a concealed weapon and for manslaughter on an unarmed person inflicted with a knife that was previously concealed. Prayers The act mandates a reduction in parole eligibility for both offences and creates a second or subsequent offence for carrying a concealed weapon, as well as including carrying a concealed weapon as an ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS offence within the absolute jurisdiction of a provincial court judge. Ï (1000) The act would also provide direction to sentencing courts with [English] respect to consideration and calculation of pre-trial custody. ORDER IN COUNCIL APPOINTMENTS The act provides direction to the National Parole Board with Hon. Dominic LeBlanc (Parliamentary Secretary to the respect to supplying relevant information to crime victims, asserts Leader of the Government in the House of Commons, Lib.): the obligation of the board to not adjourn conditional release Mr. Speaker, I am pleased to table, in both official languages, a hearings without justification and creates a future conditional release number of orders in council recently made by the government. eligibility consequence for offenders that waive scheduled hearings. *** This bill is for Andy. -

BLACK MASCULINITIES and SPORT in CANADA Gama1 Abdel-Shehid

WHO DA' IMAN: BLACK MASCULINITIES AND SPORT IN CANADA Gama1 Abdel-Shehid A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial filfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate in Philosophy Graduate Programme in Sociology York University North York Ontario Decernber 1999 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie Wellington OtiawaON KIAON4 OttawaON K1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Who Da' Man: Black Masculinities and Sport in Canada Gama1 Abdel-Shehid by a dissertation subrnitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of York University in partial fulfillrnent of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY O Permission has been granted to the LIBRARY OF YORK UNIVERSITY to tend or sell copies of this dissertation, to the NATIONAL LISRARY OF CANADA to microfilm this dissertation and to lend or sell copies of the film. -

COLCPE Automatic Contributors

Every contribution helps ost supporters of the NALC’s political action fund give through automatic deductions from Mtheir paycheck, annuity or a bank account, and we begin our annual tribute with these reliable donors. This section lists active and retired members who made donations through payroll deduction or through automatic deductions from an annuity or bank account in 2014. Automatic deduction, including those who give at the “Gimme 5” level of $5 per pay period, is easy—you sign up and you’re done. No check to write, and the donation is spread out across the year. Automatic donations are also helpful to COLCPE, since a steady source of funds allows for easier budget choices to put the funds to best use. Supporters who made both automatic deductions and additional separate, occasional donations will fi nd their names listed only in this section with their totals including both kinds of donation. If you aren’t already making automatic deductions to support COLCPE, please go to nalc.org/colcpe to learn how to sign up. Kristine Walker-Wilder $130 Lucien Drass $1650 Lisa Stewart $260 Carman Montgomery $85 Alabama Jackie Warner $20 Michael Driver $260 Bobby Tanner $120 Glen Moore $100 Branch 106, Montgomery Jacqueline White $130 Michael Eckley $60 John Taylor $260 Terrance Nelson Sr. $10 Gerald Campbell $30 James Williams $240 William Ellis $130 Clay Thomas $240 Ivan Parker $125 Booker Carroll $120 John Williams $130 Charles Glascock $65 Jeffery Tucker $130 Debbie Pettway $40 Jeffery Chandler $130 Stacy Williams Sr. $130 Kenneth Harper $130 Kerry Wengert II $130 Harold Ray $240 Genell Cheeseboro $52 Charlie Wood $60 Larry Henderson $130 Kim Whitt $250 Eric Reid $130 Sandra Chestnut $130 Daniel Wormely $130 Michael Hicks $260 John Winston $520 Fredrick Rogers $130 Richard Hogan $130 Francis Cochran $120 Anita Wright $60 Clyde Wood Jr.