Evidence from Kazakhstan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov

SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV CHOKAN OF WORKS SELECTED SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV Pioneering Ethnographer and Historian of the Great Steppe When Chokan Valikhanov died of tuberculosis in 1865, aged only 29, the Russian academician Nikolai Veselovsky described his short life as ‘a meteor flashing across the field of oriental studies’. Set against his remarkable output of official reports, articles and research into the history, culture and ethnology of Central Asia, and more important, his Kazakh people, it remains an entirely appropriate accolade. Born in 1835 into a wealthy and powerful Kazakh clan, he was one of the first ‘people of the steppe’ to receive a Russian education and military training. Soon after graduating from Siberian Cadet Corps at Omsk, he was taking part in reconnaissance missions deep into regions of Central Asia that had seldom been visited by outsiders. His famous mission to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, which began in June 1858 and lasted for more than a year, saw him in disguise as a Tashkent mer- chant, risking his life to gather vital information not just on current events, but also on the ethnic make-up, geography, flora and fauna of this unknown region. Journeys to Kuldzha, to Issyk-Kol and to other remote and unmapped places quickly established his reputation, even though he al- ways remained inorodets – an outsider to the Russian establishment. Nonetheless, he was elected to membership of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and spent time in St Petersburg, where he was given a private audience by the Tsar. Wherever he went he made his mark, striking up strong and lasting friendships with the likes of the great Russian explorer and geographer Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tian-Shansky and the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. -

Abstracts English

International Symposium: Interaction of Turkic Languages and Cultures Abstracts Saule Tazhibayeva & Nevskaya Irina Turkish Diaspora of Kazakhstan: Language Peculiarities Kazakhstan is a multiethnic and multi-religious state, where live more than 126 representatives of different ethnic groups (Sulejmenova E., Shajmerdenova N., Akanova D. 2007). One-third of the population is Turkic ethnic groups speaking 25 Turkic languages and presenting a unique model of the Turkic world (www.stat.gov.kz, Nevsakya, Tazhibayeva, 2014). One of the most numerous groups are Turks deported from Georgia to Kazakhstan in 1944. The analysis of the language, culture and history of the modern Turkic peoples, including sub-ethnic groups of the Turkish diaspora up to the present time has been carried out inconsistently. Kazakh researchers studied history (Toqtabay, 2006), ethno-political processes (Galiyeva, 2010), ethnic and cultural development of Turkish diaspora in Kazakhstan (Ibrashaeva, 2010). Foreign researchers devoted their studies to ethnic peculiarities of Kazakhstan (see Bhavna Dave, 2007). Peculiar features of Akhiska Turks living in the US are presented in the article of Omer Avci (www.nova.edu./ssss/QR/QR17/avci/PDF). Features of the language and culture of the Turkish Diaspora in Kazakhstan were not subjected to special investigation. There have been no studies of the features of the Turkish language, with its sub- ethnic dialects, documentation of a corpus of endangered variants of Turkish language. The data of the pre-sociological surveys show that the Kazakh Turks self-identify themselves as Turks Akhiska, Turks Hemshilli, Turks Laz, Turks Terekeme. Unable to return to their home country to Georgia Akhiska, Hemshilli, Laz Turks, Terekeme were scattered in many countries. -

Zhanat Kundakbayeva the HISTORY of KAZAKHSTAN FROM

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF THE REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN THE AL-FARABI KAZAKH NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Zhanat Kundakbayeva THE HISTORY OF KAZAKHSTAN FROM EARLIEST PERIOD TO PRESENT TIME VOLUME I FROM EARLIEST PERIOD TO 1991 Almaty "Кazakh University" 2016 ББК 63.2 (3) К 88 Recommended for publication by Academic Council of the al-Faraby Kazakh National University’s History, Ethnology and Archeology Faculty and the decision of the Editorial-Publishing Council R e v i e w e r s: doctor of historical sciences, professor G.Habizhanova, doctor of historical sciences, B. Zhanguttin, doctor of historical sciences, professor K. Alimgazinov Kundakbayeva Zh. K 88 The History of Kazakhstan from the Earliest Period to Present time. Volume I: from Earliest period to 1991. Textbook. – Almaty: "Кazakh University", 2016. - &&&& p. ISBN 978-601-247-347-6 In first volume of the History of Kazakhstan for the students of non-historical specialties has been provided extensive materials on the history of present-day territory of Kazakhstan from the earliest period to 1991. Here found their reflection both recent developments on Kazakhstan history studies, primary sources evidences, teaching materials, control questions that help students understand better the course. Many of the disputable issues of the times are given in the historiographical view. The textbook is designed for students, teachers, undergraduates, and all, who are interested in the history of the Kazakhstan. ББК 63.3(5Каз)я72 ISBN 978-601-247-347-6 © Kundakbayeva Zhanat, 2016 © al-Faraby KazNU, 2016 INTRODUCTION Данное учебное пособие is intended to be a generally understandable and clearly organized outline of historical processes taken place on the present day territory of Kazakhstan since pre-historic time. -

Tonyukuk and Turkic State Ideology “Mangilik

THE TONYUKUK AND AN ANCIENT TURK’S STATE IDEOLOGY OF “MANGILIK EL” PJAEE, 17 (6) (2020) THE TONYUKUK AND AN ANCIENT TURK’S STATE IDEOLOGY OF “MANGILIK EL” Nurtas B. SMAGULOV, PhD student of the of the Department of Kazakhstan History, L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Kazakhstan, [email protected] Aray K. ZHUNDIBAYEVA, PhD, Head of the Department of Kazakh literature, accociate professor of the Department of Kazakh literature, Shakarim state University of Semey (SSUS), (State University named after Shakarim of city Semey), Kazakhstan, [email protected] Satay M. SIZDIKOV, Doctor of historical science, professor of the Department of Turkology, L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Kazakhstan, [email protected] Arap S. YESPENBETOV, Doctor of philological science, professor of the Department of Kazakh literature, Shakarim state University of Semey (SSUS), (State University named after Shakarim of city Semey), Kazakhstan, [email protected] Ardak K. KAPYSHEV, Candidate of historical science, accociate professor of the Department of International Relations, History and Social Work, Abay Myrzkhmetov Kokshetau University, Kazakhstan, [email protected] Nurtas B. SMAGULOV, Aray K. ZHUNDIBAYEVA, Satay M. SIZDIKOV, Arap S. YESPENBETOV, Ardak K. KAPYSHEV: The Tonyukuk And An Ancient Turk’s State Ideology Of “Mangilik El” -- Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(6). ISSN 1567-214x ABSTRACT Purpose of the study. Studying and evaluating the activities of Tonykuk, who was the state adviser to the Second Turkic Kaganate, the main ideologist responsible for the ideological activities of the Kaganate from 682 to 745, is an urgent problem of historical science. In the years 646-725 he worked as an adviser on political and cultural issues of the three Kagan. -

Canyons of the Charyn River (South-East Kazakhstan): Geological History and Geotourism

GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites Year XIV, vol. 34, no. 1, 2021, p.102-111 ISSN 2065-1198, E-ISSN 2065-0817 DOI 10.30892/gtg.34114-625 CANYONS OF THE CHARYN RIVER (SOUTH-EAST KAZAKHSTAN): GEOLOGICAL HISTORY AND GEOTOURISM Saida NIGMATOVA Institute of Geological Sciences named after K.I. Satpaev, Almaty, Republic of Kazakhstan, e-mail: [email protected] Aizhan ZHAMANGARА L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Satpayev Str., 2, 010008 Nur-Sultan, Republic of Kazakhstan, Institute of Botany and Phytointroduction, e-mail: [email protected] Bolat BAYSHASHOV Institute of Geological Sciences named after K.I. Satpaev, Almaty, Republic of Kazakhstan, e-mail: [email protected] Nurganym ABUBAKIROVA L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Satpayev Str., 2, 010008 Nur-Sultan, Republic of Kazakhstan, e-mail: [email protected] Shahizada AKMAGAMBET L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Satpayev Str., 2, 010008 Nur-Sultan, Republic of Kazakhstan, e-mail: [email protected] Zharas ВERDENOV* L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Satpayev Str., 2, 010008 Nur-Sultan, Republic of Kazakhstan, e-mail: [email protected] Citation: Nigmatova, S., Zhamangara, A., Bayshashov, B., Abubakirova, N., Akmagambet S., & Berdenov, Zh. (2021). CANYONS OF THE CHARYN RIVER (SOUTH-EAST KAZAKHSTAN): GEOLOGICAL HISTORY AND GEOTOURISM. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 34(1), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.34114-625 Abstract: The Charyn River is located in South-East Kazakhstan, 195 km east of Almaty. The river valley cuts through Paleozoic rocks and loose sandy-clay deposits of the Cenozoic and forms amazingly beautiful canyons, the so-called "Valley of Castles". -

Germans from Crimea in Labor Camps of Swerdlowsk District

GERMANS FROM CRIMEA IN LABOUR CAMPS OF SWERDLOWSK DISTRICT By Hilda Riss, printed in Landsmannschaft der Deutschen aus Russland Heimatbuch 2007/2008. Pages 58 – 91. Translation and publication by permission. Translation and all footnotes by Merv Weiss. Hilda Riss, born 03 December 1935 in Rosental, Crimea, was deported in the middle of August 1941 with her family to Siberia, where nevertheless, she was able to enjoy a good education. She completed her secondary schooling and after that she was a teacher and director of the library in Usmanka, Kemerowo district. She studied at the State University of Tomsk from 1957 to 1962. After her academic studies, Hilda Riss was an associate of the Institute of Crop Management in Alma-Ata until 1982, and from 1983 until her retirement in 1991, a leading agronomist, that is to say, a senior scientific associate in Kazakhstan. From 1959 to 1996 she published 5 books in Russian under the name “Galina Kosolapowa” and one book in the Tschechnian language on the subject of crop protection. In 1969 she qualified for a scholarship and in 1972 in Moscow received her certificate as senior scientific associate of entomology. After her retirement and particularly after her emigration to Germany in 1995, Hilda Riss increasingly turned her attention to the research of her fellow Germans from Crimea. She wrote her sixth book “Krim nascha Rodina” [Crimea, our Fatherland - MW] in Russian because she wanted to communicate with those German-Russian generations who were not able to attend a German school, in order to keep in contact with them, and togather material for a memorial book of the Crimean Germans in the German language. -

Plant Genetics, Genomics, Bioinformatics and Biotechnology" (Plantgen2017)

PROCEEDINGS of the 4th International conference "Plant Genetics, Genomics, Bioinformatics and Biotechnology" (PlantGen2017) Best Western Plus Atakent Park Hotel May 29 – June 02, 2017, Almaty, Kazakhstan УДК 581 (063) ББК 28.5 Р71 "Plant Genetics, Genomics, Bioinformatics and Biotechnology": Материалы Международной конференции 4th International conference PlantGen2017 / под общей редакцией Е.К. Туруспекова, С.И. Абугалиевой. – Алматы: ИББР, 2017 – 216 с. ISBN 978-601-80631-2-1 В сборнике представлены материалы 4 Международной конференции по генетике, геномике, биоинформатике и биотехнологии растений (PlantGen2017), проведенной в г. Алматы 29 мая -2 июня 2017 г. В публикациях изложены результаты оригинальных исследований в области изучения, сохранения и использования генетических ресурсов, генетики и селекции, биоинформатики и биотехнологии растений. Сборник рассчитан на биологов, генетиков, биотехнологов, селекционеров, специалистов, занимающихся генетическими ресурсами растений, и студентов биологического и сельско-хозяйственного профиля. Тезисы докладов представлены в авторской редакции. Рекомендовано к изданию Ученым советом РГП «Института биологии и биотехнологии растений» Комитета науки Министерства образования и науки Республики Казахстан (Протокол № 2 от 04.05.2017 г.). УДК 581 (063) ББК 285 ISBN 978-601-80631-2-1 © ИББР, 2017 2 Proceedings of the 4th International Conference "Plant Genetics, Genomics, Bioinformatics and Biotechnology" (PlantGen2017) May 29 – June 02 2017 – Almaty, Kazakhstan Editors Yerlan Turuspekov, Saule Abugalieva Publisher Institute of Plant Biology and Biotechnology Plant Molecular Genetics Lab ISBN: 978-601-80631-2-1 Responsibility for the text content of each abstract is with the respective authors. Date: May 29 – June 02 2017 Venue: Best Western Plus Atakent Park Hotel, 42 Timiryazev str., 050040 Almaty, Kazakhstan Conference webpage: http://primerdigital.com/PlantGen2017/en/ Hosted by: Institute of Plant Biology and Biotechnology (IPBB), Almaty, Kazakhstan Correct citation: Turuspekov Ye., Abugalieva S. -

Ad Alta Journal of Interdisciplinary Research

AD ALTA JOURNAL OF INTERDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH NEGATIVE CONSEQUENCES OF THE COUNTRY’S COLONIZATION OF KAZAKHSTAN aDAULET ABENOV, bUZAKBAI ISMAGULOV, cBIBIGUL Kazakhstan. From history, it is known that the accession of ABENOVA, dGULMIRA KUPENOVA, eNURLAN YESETOV, Kazakhstan to Russia is closely connected with the name of the fASYLBEK MADEN, gAIDYN ABDENOV Abulkhair Khan of the Younger Zhuz. As has been said, colonization is usually accompanied by the forcible seizure of a-gK. Zhubanov Regional State University of Aktobe, 030000, 34 foreign territory. A. Moldagulova Ave., Aktobe, Kazakhstan email: [email protected], [email protected], But in this case, Abulkhair Khan himself wanted to obtain [email protected], [email protected], Russian citizenship, based not only on his personal interests but [email protected], [email protected], also to provide protection from enemies, mainly from the [email protected] Dzungars. Therefore, Kazakhstan's accession to Russia can be considered voluntary, although it was based on a unilateral policy. The Khan's first appeal to Russia remained unanswered. Abstract: In the article, on the basis of an objective investigation and usage, for the first time, archival documents introduced into scientific circulation and materials of However, when, in 1730, influential biys instructed Abulkhair to the pre-revolutionary press, the essence of a colonial policy of the imperial government in Western Kazakhstan is analyzed. For a long time, the country's negotiate with the Russian government on the conclusion of a colonization was estimated unambiguously as the progressive phenomenon, tragic military alliance, the khan accepts Russian citizenship. (3) This consequences of this policy in the social, economic and spiritual life of the Kazakh played an important role in the future situation of the entire people were not shown. -

Environment and Development Nexus in Kazakhstan

ENVIRONMENT AND DEVELOPMENT NEXUS IN KAZAKHSTAN Environment and Development Nexus in Kazakhstan A series of UNDP publication in Kazakhstan, #UNDPKAZ 06 Almaty, 2004 1 ENVIRONMENT AND DEVELOPMENT NEXUS IN KAZAKHSTAN Report materials could be reproduced in other publications, without prior permission of UNDP, provided proper reference is made to this publication. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of UNDP. Printed in “LEM Printhouse” 78a Baitursynov Street Almaty, Republic of Kazakhstan Phone/Fax: 7(3272) 922-651 2 ENVIRONMENT AND DEVELOPMENT NEXUS IN KAZAKHSTAN Foreword by the Minister of Environmental Protection of the Republic of Kazakhstan Dear Ladies and Gentlemen! In his speech at the World Summit for Sustainable Development, the President of Kazakhstan reminded the world community of the global scale of the processes that are underway, and called for prevention of irreversible harm to the environment in order to preserve the necessary life resources for our descendants. Environmental safety and sustainable development issues are of vital importance for Kazakhstan. Water resource deficit and significant land degradation, the Aral Sea disaster, the aftermath of the nuclear tests, accumulation of industrial waste, oil spills – all these problems are no longer fall under the category of environmental ones. Many of these problems are regional and even global. Coordinated interaction between the mankind and the environment and ensuring a safe environment are one of the priorities of the long-term Kazakhstan-2030 Strategy. It has clear-cut provisions: “...increase efforts in making our citizens healthy during their life time, and enjoying a healthy environment”. -

Notes on the Lighting Devices in the Medicine Buddha Transformation Tableau in Mogao Cave 220, Dunhuang by Sha Wutian 沙武田

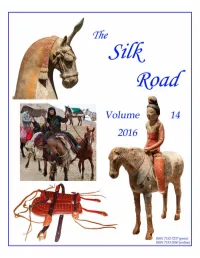

ISSN 2152-7237 (print) ISSN 2153-2060 (online) The Silk Road Volume 14 2016 Contents From the editor’s desktop: The Future of The Silk Road ....................................................................... [iii] Reconstruction of a Scythian Saddle from Pazyryk Barrow № 3 by Elena V. Stepanova .............................................................................................................. 1 An Image of Nighttime Music and Dance in Tang Chang’an: Notes on the Lighting Devices in the Medicine Buddha Transformation Tableau in Mogao Cave 220, Dunhuang by Sha Wutian 沙武田 ................................................................................................................ 19 The Results of the Excavation of the Yihe-Nur Cemetery in Zhengxiangbai Banner (2012-2014) by Chen Yongzhi 陈永志, Song Guodong 宋国栋, and Ma Yan 马艳 .................................. 42 Art and Religious Beliefs of Kangju: Evidence from an Anthropomorphic Image Found in the Ugam Valley (Southern Kazakhstan) by Aleksandr Podushkin .......................................................................................................... 58 Observations on the Rock Reliefs at Taq-i Bustan: A Late Sasanian Monument along the “Silk Road” by Matteo Compareti ................................................................................................................ 71 Sino-Iranian Textile Patterns in Trans-Himalayan Areas by Mariachiara Gasparini ....................................................................................................... -

New Urbanization of the Steppe. Astana: a Capital Called the Capital

STUDIA HISTORIAE OECONOMICAE UAM Vol. 31 Poznań 2013 Marek G a w ę c k i (Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań) NEW URBANIZATION OF THE STEPPE. ASTANA: A CAPITAL CALLED THE CAPITAL Relocating the capital of Kazakhstan from Almaty to Akmola (then renamed Astana) in 1997 has been the subject of an intense debate, particularly within media. The process of creating the new capital of Kazakhstan should consider the broader perspective of historical, political and ideologi- cal, social, climatic and geographical factors, and finally to put the matter in terms of architecture and urban planning. The author considers this very broad perspective, finally expressing the hope that the project of “the city of the future” analyzed in the article, will become a permanent part of the Kazakh reality. Keywords: urban history, urban and spatial development, post-Soviet politics doi:10.2478/sho-2013-0003 Relocating the capital of Kazakhstan, from Almaty to Akmola (then re- named Astana), in 1997, has been the subject of an intense debate, partic- ularly within media. It has sparked controversy and brought about some radical opinions, ranging from mockery to ecstasy. While some call it “The Disneyland in the steppe”, “The New Potemkin Village” and “The Borat’s Capital”, others praise its futuristic architecture and the grand scale of the enterprise. A couple of academic papers on this topic have also appeared1. 1 It is worth mentioning the most important: R.L. Wolfel, North to Astana: Nationalistic Motives for the Movement of the Kazakh(stani) Capital, Nationalities Papers, vol.30, No.3, 2002; L. Yacher, Kazakhstan: Megadream, Megacity, Megadestiny?, [in:] S.D. -

2-52 Figure 2.3.8-3 Drawing of Typical Pump Station (Large Size)

Detailed Design Study of Water Supply and Sewerage System for Astana City Final Report Figure 2.3.8-3 Figure – 3/3 Size) (Large Station Pump Typical of Drawing 2-52 Detailed Design Study of Water Supply and Sewerage System for Astana City Final Report 4) Sewers and Manholes ⅰ) Sewers Inventory of sewers was investigated. Construction of sewers started in 1951. The inventory of a total sewer length of 226.6km provides information on location, diameter, length, material type, construction year and manhole numbers in each pipeline. Figure 2.3.9 shows the sewage collection network. Specific feature of the network is as shown below: - A pressure line basically consists of double lines. - Pressure lines are made of steel pipe, 14% of total length - Cast-iron pipe is broadly used, 40% of total length. - Concrete pipe is relatively low in composition percentage. - Asbestos-cement has about 20 %, most of them are utilized for small diameter pipeline below 300mm. - Use of asbestos-cement pipe is not restricted at present, which may cause the lung disease asbestosis. Table 2.3.10 Composition of Different Pipe Materials Pipe Material Length (m) Percentage Remarks Asbestos-cement 45,461.51 20.1 Cast-iron 85,380.96 37.7 Ceramics 32,574.45 14.4 Reinforced concrete 27,929.70 12.3 Mainly gravity collector Polyethylene 2,240.00 1.0 Steel 32,264.80 14.2 Mainly pressure collector Other 727.00 0.3 TOTAL 226,578.42 100.0 As for the installation depth of sewers, some pressure lines are installed above the ground.