Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dialectical Theology As Theology of Mission: Investigating the Origins of Karl Barth’S Break with Liberalism

International Journal of Systematic Theology Volume 16 Number 4 October 2014 doi:10.1111/ijst.12075 Dialectical Theology as Theology of Mission: Investigating the Origins of Karl Barth’s Break with Liberalism DAVID W. CONGDON* Abstract: Based on a thorough investigation of Karl Barth’s early writings, this article proposes a new interpretation of dialectical theology as fundamentally concerned with the issue of mission. Documents from 1914 and 1915 show that the turning point in Barth’s thinking about mission – and about Christian theology in general – occurred, at least in part, in response to a largely forgotten manifesto published in September 1914. This manifesto appealed to Protestants around the world to support Germany’s cause in the war on the grounds that they would be supporting the work of the Great Commission. Barth’s reaction to this document sheds light on the missionary nature of dialectical theology, which pursues an understanding of God and God-talk that does not conflate the mission of the church with the diffusion of culture. The term ‘dialectical theology’ is generally associated with notions like Christocentrism, God as wholly other, the infinite qualitative distinction between time and eternity, the negation of the negation, the analogy of faith (analogia fidei) and ‘faith seeking understanding’ (fides quaerens intellectum). These are all important concepts that have their place in articulating the theology that Karl Barth initiated.And yet, as important as questions of soteriology and epistemology undoubtedly are for Barth, documents from before and during his break with liberalism indicate that one of his central concerns was the missionary task of the church. -

Pastor Johann Christoph Blumhardt

Johann Christoph Blumhardt (1802–1880). Courtesy of Plough Publishing House. Blumhardt Series Christian T. Collins Winn and Charles E. Moore, editors Pastor Johann Christoph Blumhardt An Account of His Life Friedrich Zündel edited by Christian T. Collins Winn and Charles E. Moore Translated by Hugo Brinkmann PLOUGH PUBLISHING Translated from Friedrich Zündel, Johann Christoph Blumhardt: Ein Lebensbild, 4th edition (Zürich: S. Höhr, 1883). Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com Copyright © 2015 by Plough Publishing House. All rights reserved. PRINT ISBN: 978-1-60899-406-9 (Cascade Books) EPUB ISBN: 978-0-87486-751-0 MOBI ISBN: 978-0-87486-752-7 PDF ISBN: 978-0-87486-753-4 Contents Series Foreword by Christian T. Collins Winn and Charles E. Moore | vii Foreword by Dieter Ising | ix Acknowledgments | xiii PART ONE: Years of Growth and Preparation First section: introduction—Childhood and Youth 1 The Native Soil | 3 2 Birth and Childhood | 9 3 At the University | 20 Second section: the Candidate 4 Dürrmenz | 34 5 Basel | 37 6 Iptingen | 51 PART TWO: Möttlingen First section: introduction—the Early days 7 Previous Rectors of Möttlingen | 91 8 Installation, Wedding, Beginning of Ministry | 101 Second section: the struggle 9 The Illness of Gottliebin Dittus | 117 Third section: the awakening 10 The Movement of Repentance | 158 11 The Miracles | 205 12 Blumhardt’s Message and Expectant Hopes | 246 13 Expectancy as Expressed in Blumhardt’s Writings | 298 14 Worship Services -

From Village Boy to Pastor

1 From Village Boy to Pastor CHILDHOOD, YOUTH, AND STUDENT DAYS Rüdlingen is a small farming village in the Canton of Schaffhausen, situated in northern Switzerland. The village is surrounded by a beauti- ful countryside only a few miles downriver from the Rhine Falls. Fertile fields extend toward the river, and steep vineyards rise behind the village. The Protestant church sits enthroned high above the village. Almost all of the villagers belonged to the Protestant faith. Adolf Keller was born and raised in one of Rüdlingen’s pretty half-timbered houses in 1872. He was the eldest child born to the village teacher Johann Georg Keller and his wife Margaretha, née Buchter. Three sisters and a brother were born to the Kellers after Adolf.SAMPLE A large fruit and vegetable garden contributed to the upkeep of the family. For six years, Adolf Keller attended the primary school classes taught by his father. The young boy’s performance so conspicuously excelled that of his sixty peers that the highly regarded village teacher decided not to award his son any grades. Occasionally, Keller senior involved his son in the teaching of classes. Both parents were ecclesiastically minded. Keller’s father took his Bible classes seriously. Adolf was required to learn by heart countless Bible verses. His mother ran the village Sunday School. She was a good storyteller. Unlike her more austere husband, Keller’s mother represented an emotional piety. She never missed attending the annual festival of the devout Basel Mission. 1 © 2013 The Lutterworth Press Adolf Keller The village of Rüdlingen and the Rhine (old picture postcard) The village pastor taught the young Keller Latin, and his daughter, who had traveled widely in Europe as a governess, taught him English and French. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The case for theological ethics: an appreciation of Ernil Brunner and Reinhold Niebuhr as moral theologians Hamlyn, Eric Crawford How to cite: Hamlyn, Eric Crawford (1990) The case for theological ethics: an appreciation of Ernil Brunner and Reinhold Niebuhr as moral theologians, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/6271/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 THE CASE FOR THEOLOGICAL ETHICS An appreciation of Emil Brunner and Reinhold Niebuhr as moral theologians. Submitted by Eric Crawford Hamlyn Qualification for which it is submitted- M.A. University of Durham Department of Theology. 1990 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. CONTENTS -

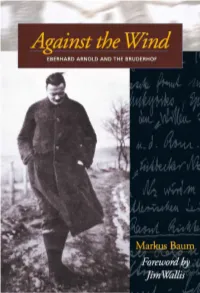

Against the Wind E B E R H a R D a R N O L D a N D T H E B R U D E R H O F

Against the Wind E B E R H A R D A R N O L D A N D T H E B R U D E R H O F Markus Baum Foreword by Jim Wallis Original Title: Stein des Anstosses: Eberhard Arnold 1883–1935 / Markus Baum ©1996 Markus Baum Translated by Eileen Robertshaw Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com Copyright © 2015, 1998 by Plough Publishing House All rights reserved Print ISBN: 978-0-87486-953-8 Epub ISBN: 978-0-87486-757-2 Mobi ISBN: 978-0-87486-758-9 Pdf ISBN: 978-0-87486-759-6 The photographs on pages 95, 96, and 98 have been reprinted by permission of Archiv der deutschen Jugendbewegung, Burg Ludwigstein. The photographs on pages 80 and 217 have been reprinted by permission of Archive Photos, New York. Contents Contents—iv Foreword—ix Preface—xi CHAPTER ONE 1 Origins—1 Parental Influence—2 Teenage Antics—4 A Disappointing Confirmation—5 Diversions—6 Decisive Weeks—6 Dedication—7 Initial Consequences—8 A Widening Rift—9 Missionary Zeal—10 The Salvation Army—10 Introduction to the Anabaptists—12 Time Out—13 CHAPTER TWO 14 Without Conviction—14 The Student Christian Movement—14 Halle—16 The Silesian Seminary—18 Growing Responsibility in the SCM—18 Bernhard Kühn and the EvangelicalAlliance Magazine—20 At First Sight—21 Against the Wind Harmony from the Outset—23 Courtship and Engagement—24 CHAPTER THREE 25 Love Letters—25 The Issue of Baptism—26 Breaking with the State Church—29 Exasperated Parents—30 Separation—31 Fundamental Disagreements among SCM Leaders—32 The Pentecostal Movement Begins—33 -

HTS 63 4 KRITZINGER.Tambach REVISED.AUTHOR

“The Christian in society”: Reading Barth’s Tambach lecture (1919) in its German context J N J Kritzinger Department of Christian Spirituality, Church History and Missiology University of South Africa Abstract This article analyses Karl Barth’s 1919 Tambach lecture on “The Christian in society” in the context of post World War I Europe. After describing Barth’s early life and his move away from liberal theology, the five sections of the Tambach lecture are analysed. Barth’s early dialectical theology focussed on: Neither secularising Christ nor clericalising society; Entering God’s movement in society; Saying Yes to the world as creation (regnum naturae) ; Saying No to evil in society (regnum gratiae) ; respecting God’s reign as beyond our attempts (regnum gloriae) . 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The approach of this paper This article should be read together with the one following it, since the two papers were conceived and born together. Rev B B Senokoane and I made a joint presentation to the conference on “Reading Karl Barth in South Africa today,” which was held in Pretoria on 10-11 August 2006. In the subsequent reworking of the material for publication, it became two articles. This article analyses the 1919 Tambach lecture of Karl Barth in its post World War I German context, to get a sense of the young Barth’s theological method and commitment. The second article uses Barth’s approach, as exhibited in that lecture, to theologise in South Africa, stepping into his shoes and “doing a Tambach” today. The first move is an exercise in historical interpretation and the second in contemporary imagination. -

Inhalt*OLHGHUXQJ

9 Inhalt*OLHGHUXQJ 1 Die Auseinandersetzung zwischen Hermann Kutter und Leonhard Ragaz (1912) 1.1 Der Zürcher Generalstreik 17 1.2 Der Offene Brief Hermann Kutters 19 1.3 Die Entgegnung Leonhard Ragaz’ 20 2 Die „NEUEN WEGE“ 26 3 Der Streit zwischen Paul Wernle und Leonhard Ragaz (1913) 3.1 Ein Ende und ein Anfang 30 3.2 Alt und Neu: eine Auseinandersetzung 3.2.1 Der Offene Brief Paul Wernles 33 3.2.2 Die Verteidigung Leonhard Ragaz’ 37 3.3 Relative und absolute Hoffnung 41 3.4 Der Streit droht zu eskalieren 50 3.4.1 Ein zweiter „offener Brief“ Paul Wernles an die Redaktion der NEUEn WEGE 50 3.4.2 Leonhard Ragaz verhindert die Veröffentlichung 51 3.4.3 Paul Wernle lenkt ein 53 3.4.4 Leonhard Ragaz dankt Paul Wernle 54 4 „Auf das Reich Gottes warten“ (1916) 4.1 Der Kon À ikt zwischen Karl Barth und Leonhard Ragaz 57 4.2 Die Bedenken des Schriftleiters Leonhard Ragaz 58 4.3 Die Antworten Karl Barths 60 4.4 Die Antwort Leonhard Ragaz’ 65 4.5 Wie geht es weiter mit der Buchbesprechung? 70 4.6 Mutmaßungen über den Kon À ikt 73 4.7 Wer versteht Christoph Blumhardt am besten? 76 4.8 Das „Bollertum“ 80 5DJD]B%XFKLQGE 10 GliederungInhalt 5 Der Kon À ikt und seine Folgen 5.1 Da scheiden sich die Geister 86 5.2 Karl Barth Römerbrief – Kommentar, 1. und 2. Au À age Getrennte Wege 89 6 Christoph Blumhardt und seine Botschaft im Spiegel der Literatur. -

<Tlnurnrbtu Mqrnlngtral:Sltn1ljly

<tLnurnrbtu mqrnlngtral:SLtn1lJly . Continuing LEHRE UND WEHRE MAGAZIN FUER Ev.-LuTH. HO~ULETIK THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY-THEOLOGICAL MONTHLY Vol. XV June, 1944 No.6 CONTENTS Page Karl Barth. John Jrheodore Mueller _... _._..... :....... _._... _ ........... _...... 361 The Right and Wrong 9~ Private Judgment. Th. Engelder ............ 385 Outlines on the Standard Gospels ..... ................... ,•..................... :.......... 403 Miscellanea ................... _.............................. ,...................... ~................. :........... 410 Theological Observer .......... _...................... _............... _... _....................... "... 418 Book Rev!ew .......... "........................................ _............ __ ........................ ,............ 427 Ein Prediger muss nlcht alleln tOei Es 1st kein Ding. das die Leute dim, also dass er die Schafe unter mehr bei der Kirche· bebaelt denn weise. wi~sie recht4;!Christen sollen die gute Predigt. -Apologie, An. 24 seln.sondern auch daneben den Woe! fen tOehTlm, dass me die Schafe nlcht angreifen und mit falscher Lehre ver If tb-e trumpet give an uncertain fuehren und Irrtum elnfuehren. sound. who shall prepare himself to LutheT the battle? -1 Cor. 14:8 Published for the Ev. Luth. Synod of Missouri, Ohio, and Other States CONCORDIA PUBLISIDNG HOUSE, St. Louis 18, Mo; PRIN'l'ED IN u. S. A. ABOH1V Concordia Theological Monthly Vol. xv JUNE. 1944 No.6 Karl Barth For this essay we have chosen a simple title: Karl Barth. We could not do otherwise. As yet it -

Examining the Primary Influence on Karl Barth's Epistle to the Romans

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University B. R. Lakin School of Religion Examining the Primary Influence on Karl Barth’s Epistle to the Romans Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the MARS Degree: Area of Specialization: Philosophical Theology By Sean Turchin June 20, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Chapter 1. IN THE WAKE OF KANTIANISM: ESTABLISHING THE THEOLOGICAL CONTEXT OF 19TH AND 20TH CENTURY THOUGHT WHEREIN ROMANS II WAS INTRODUCED Barth and Kantianism p.7 Barth and Schleiermacherianism p.14 Barth and Ritschlianism p.17 Barth and Herrmannianism p. 20 Barth and neo-Kantianism p. 30 Reactionary Theology: The Relationship of Barth’s Römerbrief to His Early Theology p. 39 1. Breaking with Liberalism: Immanentism and Social Ethics p. 39 2. Dropping the “Bomb”: The Publication of Romans I p. 43 Chapter 2. EXAMINING THE REFORMULATION OF ROMANS I AND THE PUBLICATION OF ROMANS II The Need and Tools for Reformulation p. 47 The Theme of Romans II p. 51 Chapter 3. KIERKEGAARD OR NEO-KANTIANISM: CORRELATING THEMES AND INFLUENCES WITHIN ROMANS II The Kierkegaard Reception in Late 19th and 20th Century Germany p. 55 The Infinite Qualitative Distinction p. 59 1. Dialectic of Time and Eternity p. 61 2. Urgeschichte and Christianity p. 64 3. The Dialectic of Christ and Adam p. 75 Knowledge of God p. 79 1. Idea or Reality: Barth and the neo-Kantian conception of Ursprung p. 79 2. Paradox: The Dialectic of Veiling and Unveiling p. -

Vorlesung: Evangelische Seelsorge (Extrablatt) Wintersemester 2013/14

Vorlesung: Evangelische Seelsorge (Extrablatt) Wintersemester 2013/14 Prof. Dr. Michael Herbst 31. Oktober 2013 EXTRABLATT 01 Wer war Eduard Thurneysen? Thurneysen wurde am 10.7.1888 in Walenstadt der Nähe von St. Gallen geboren. Sein Vater war Pfarrer. Thurneysens Zwillingsbruder starb nach drei Monaten; seine Mutter nach 2 ½ Jahren. Prägend war diese Erfahrung. Grözinger nennt ihn den „verwundeten Seelsorger“.1 Zu seiner Stiefmutter behielt er ein gespaltenes Verhältnis. Bedeutend wurde aber gerade die Stiefmutter, weil sie ihn auf Bad Boll und Christoph Blumhardt aufmerksam machte. Der junge Thurneysen, gelangweilt von den Predigten seines Vaters, reiste zu Blumhardt, wurde auf- und ernst genommen und erfuhr seine Berufung zum Theologen. Er lernte dort etwas von der „Kraft des Gesprächs“. Nach Gesprächen mit Blumhardt, so schrieb er später, wusste man innerlich wieder, wo man hingehörte und war heimgekehrt.2 Er wurde theologisch ge- prägt aber auch durch Begegnungen mit Ernst Troeltsch und Hermann Kutter (rel. Sozialis- mus). 1913 wurde Thurneysen Pfarrer in Leutwil-Dürrenesch. Er blieb bis 1920. Leutwil war Erwe- ckungsboden. Aber zugleich ein problematischer Boden: Alkoholismus, Kinderarbeit, Aus- beutung der Männer und Frauen in der Fabrik- und Heimarbeit. Thurneysen predigte und übte Seelsorge, macht viele Hausbesuche, aber er begründete auch eine Tabakarbeiterge- werkschaft und fördert die Arbeit des Blaukreuzvereins. 1 Albrecht Grözinger 1996, 277. 2 Vgl. Ibid., 279. Lehrstuhl für Praktische Theologie Prof. Dr. Michael Herbst Wenige Kilometer entfernt von Leutwil wirkt inzwischen in Safenwil sein Freund Karl Barth. Wenn Sie in Eberhard Buschs Barth-Biographie lesen, können Sie auch eine Menge über Thurneysen und seine Freundschaft zu Karl Barth erfahren. -

Examining the Primary Influence on Karl Barth's

Liberty University B. R. Lakin School of Religion Examining the Primary Influence on Karl Barth’s Epistle to the Romans Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the MARS Degree: Area of Specialization: Philosophical Theology By Sean Turchin June 20, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Chapter 1. IN THE WAKE OF KANTIANISM: ESTABLISHING THE THEOLOGICAL CONTEXT OF 19TH AND 20TH CENTURY THOUGHT WHEREIN ROMANS II WAS INTRODUCED Barth and Kantianism p.7 Barth and Schleiermacherianism p.14 Barth and Ritschlianism p.17 Barth and Herrmannianism p. 20 Barth and neo-Kantianism p. 30 Reactionary Theology: The Relationship of Barth’s Römerbrief to His Early Theology p. 39 1. Breaking with Liberalism: Immanentism and Social Ethics p. 39 2. Dropping the “Bomb”: The Publication of Romans I p. 43 Chapter 2. EXAMINING THE REFORMULATION OF ROMANS I AND THE PUBLICATION OF ROMANS II The Need and Tools for Reformulation p. 47 The Theme of Romans II p. 51 Chapter 3. KIERKEGAARD OR NEO-KANTIANISM: CORRELATING THEMES AND INFLUENCES WITHIN ROMANS II The Kierkegaard Reception in Late 19th and 20th Century Germany p. 55 The Infinite Qualitative Distinction p. 59 1. Dialectic of Time and Eternity p. 61 2. Urgeschichte and Christianity p. 64 3. The Dialectic of Christ and Adam p. 75 Knowledge of God p. 79 1. Idea or Reality: Barth and the neo-Kantian conception of Ursprung p. 79 2. Paradox: The Dialectic of Veiling and Unveiling p. 83 3. Faith and Offense p. 87 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS p. 88 BIBLIOGRAPHY p. 90 ii INTRODUCTION When Karl Barth first introduced the second edition of his Epistle to the Romans in 1921, theologian Karl Adams said it was “the bomb that fell on the playground of the theologians.”1 The bombing ground upon which Barth’s powerful, programmatic exposition fell was a theological landscape that had never emerged from the philosophical effects of Immanuel Kant’s pervasive epistemological dualism. -

An Embassy Besieged Is an Inspiration to Today’S Readers

This book reads like a modern book of Acts. It is not only a fascinating and inspiring chronicle, but one of the best inside views of the rise of the Third Reich. Barth provides an invaluable account of how a community of Christians negotiated the moral and spiritual challenges of that ter- rible time. —Robert Ellsberg, author of Modern Spiritual Classics Emmy Barth has expertly and lovingly woven together a seamless narrative that vividly chronicles the Bruderhof community’s sacrifice, heroism, faith, determination, and courage. An Embassy Besieged is an inspiration to today’s readers. —Ari L. Goldman, author of The Search for God at Harvard This moving story raises profound questions: Can we deny God’s pres- ence in any enemy? What does it mean to carry out Jesus’ command to love the enemy in the context of a nation carrying out demonic poli- cies? And how should the church act today in a national security state whose weapons and policies threaten the world? Barth’s depiction of the Bruderhof’s life and trials in Nazi Germany offers inspiration and hope for our own equally profound questions of Christian discipleship. —Jim Douglass, author of JFK and the Unspeakable Arnold once said: “To be an ambassador for God’s kingdom is some- thing tremendous. When we take this service upon us, we enter into mortal danger.” In 1937 the Gestapo confiscated the Bruderhof’s farm and dissolved their community. The few remaining members were ex- pelled under guard, apart from three men detained in prison for alleged fraud. Their escape to freedom makes a fitting close to this lively, detailed account of one community’s courageous witness to the gospel.