Citizenship in Heaven and on Earth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dialectical Theology As Theology of Mission: Investigating the Origins of Karl Barth’S Break with Liberalism

International Journal of Systematic Theology Volume 16 Number 4 October 2014 doi:10.1111/ijst.12075 Dialectical Theology as Theology of Mission: Investigating the Origins of Karl Barth’s Break with Liberalism DAVID W. CONGDON* Abstract: Based on a thorough investigation of Karl Barth’s early writings, this article proposes a new interpretation of dialectical theology as fundamentally concerned with the issue of mission. Documents from 1914 and 1915 show that the turning point in Barth’s thinking about mission – and about Christian theology in general – occurred, at least in part, in response to a largely forgotten manifesto published in September 1914. This manifesto appealed to Protestants around the world to support Germany’s cause in the war on the grounds that they would be supporting the work of the Great Commission. Barth’s reaction to this document sheds light on the missionary nature of dialectical theology, which pursues an understanding of God and God-talk that does not conflate the mission of the church with the diffusion of culture. The term ‘dialectical theology’ is generally associated with notions like Christocentrism, God as wholly other, the infinite qualitative distinction between time and eternity, the negation of the negation, the analogy of faith (analogia fidei) and ‘faith seeking understanding’ (fides quaerens intellectum). These are all important concepts that have their place in articulating the theology that Karl Barth initiated.And yet, as important as questions of soteriology and epistemology undoubtedly are for Barth, documents from before and during his break with liberalism indicate that one of his central concerns was the missionary task of the church. -

Pastor Johann Christoph Blumhardt

Johann Christoph Blumhardt (1802–1880). Courtesy of Plough Publishing House. Blumhardt Series Christian T. Collins Winn and Charles E. Moore, editors Pastor Johann Christoph Blumhardt An Account of His Life Friedrich Zündel edited by Christian T. Collins Winn and Charles E. Moore Translated by Hugo Brinkmann PLOUGH PUBLISHING Translated from Friedrich Zündel, Johann Christoph Blumhardt: Ein Lebensbild, 4th edition (Zürich: S. Höhr, 1883). Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com Copyright © 2015 by Plough Publishing House. All rights reserved. PRINT ISBN: 978-1-60899-406-9 (Cascade Books) EPUB ISBN: 978-0-87486-751-0 MOBI ISBN: 978-0-87486-752-7 PDF ISBN: 978-0-87486-753-4 Contents Series Foreword by Christian T. Collins Winn and Charles E. Moore | vii Foreword by Dieter Ising | ix Acknowledgments | xiii PART ONE: Years of Growth and Preparation First section: introduction—Childhood and Youth 1 The Native Soil | 3 2 Birth and Childhood | 9 3 At the University | 20 Second section: the Candidate 4 Dürrmenz | 34 5 Basel | 37 6 Iptingen | 51 PART TWO: Möttlingen First section: introduction—the Early days 7 Previous Rectors of Möttlingen | 91 8 Installation, Wedding, Beginning of Ministry | 101 Second section: the struggle 9 The Illness of Gottliebin Dittus | 117 Third section: the awakening 10 The Movement of Repentance | 158 11 The Miracles | 205 12 Blumhardt’s Message and Expectant Hopes | 246 13 Expectancy as Expressed in Blumhardt’s Writings | 298 14 Worship Services -

Literary Mystification: Hermeneutical Questions of the Early Dialectical Theology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at VU DOI 10.1515/NZSTh-2012-0012 NZSTh 2012; 54(3): 312–331 Katya Tolstaya Literary Mystification: Hermeneutical Questions of the Early Dialectical Theology Summary: This contribution addresses some hermeneutical problems related to Karl Barth’s Römerbrief II. First, it surveys the role of the unpublished archive materials from the Karl Barth-Archiv, i.e. the commentaries, text additions and corrections Eduard Thurneysen sent to Barth during his work on Römerbrief II. Second, because Barth and Thurneysen allude to a literary character from Dostoevsky, Ivan Karamazov, the problem of an appropriation of literature in theology is discussed. These hermeneutic problems have a deeper theological ground, exemplified in Thurneysen’s proposal for an extensive insertion in Barth’s commentary on Rom. 8:18, which was entirely adopted by Barth and thus came to function as an integral part of Barth’s commentary on Rom. 8:17–18. An appendix lists the extant documents of Thurneysen’s intensive occupation with Römerbrief II (commentaries on Barth’s manuscript, the galley and paper proofs). These documents are relevant for the genesis and chronology of Römer- brief II and yield important new insights into social, political and intellectual aspects of the Umwelt of early dialectical theology. Zusammenfassung: Dieser Beitrag behandelt einige hermeneutische Probleme in Bezug auf Karl Barths Römerbrief II. Erstens werden äußerst wichtige unpu- blizierte Archivmaterialien aus dem Karl Barth-Archiv vorgestellt, nämlich die Kommentare, Textergänzungen und Korrekturen, welche Eduard Thurneysen während der Neubearbeitung des Römerbriefs an Barth schickte. -

Faith of Christ’ in Nineteenth-Century Pauline Scholarship

The Journal of Theological Studies, NS, Vol. 66, Pt 1, April 2015 ‘EXEGETICAL AMNESIA’ AND PISSIS VQISSOT: THE ‘FAITH OF CHRIST’ IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY PAULINE SCHOLARSHIP BENJAMIN SCHLIESSER University of Zurich [email protected] Abstract Contemporary scholarship holds, almost unanimously, that Johannes Haußleiter was the first to suggest that Paul’s expression p0sti" Vristou~ should be interpreted as the ‘faith(fulness) of Christ’. His article of 1891 is said to have initiated the ongoing debate, now more current than ever. Such an assessment of the controversy’s origins, however, cannot be main- tained. Beginning already in the 1820s a surprisingly rich and nuanced discussion of the ambivalent Pauline phrase can be seen. Then, a number of scholars from rather different theological camps already con- sidered and favoured the subjective genitive. The present study seeks to recover the semantic, grammatical, syntactical, and theological aspects put forward in this past (and ‘lost’) exegetical literature. Such retrospection, while not weighing the pros and cons for the subjective or the objective interpretation, helps put into perspective the arguments and responses in the present debate. Then and now, scholars’ contextualization of their readings is in keeping with their respective diverse theological and philo- sophical frames of reference. I. INTRODUCTION One of the most recent and most comprehensive contributions to the study of Paul’s theology is Richard Longenecker’s Introducing Romans.1 Under the heading ‘Major Interpretive Approaches Prominent Today’ he deals with ‘The P0sti" Ihsou* ~ Vristou~ Theme’, arguing that this is ‘an issue that must be faced My thanks are due to Jordash KiYak both for his valuable comments and for improving the English style of this essay. -

DOKUMENTATION Hans-Ehrenberg-Preis 2011

HANS-EHRENBERG-PREIS 2011 "GOTT UND DIE POLITIK" WEGE DER VERSÖHNUNG IM ÖFFENTLICHEN LEBEN Dokumentation der Verleihung des Hans-Ehrenberg-Preises am 22. November 2011 in der Christuskirche Bochum __________________________________________________________________________________ Evangelischer Kirchenkreis Bochum Evangelische Kirche von Westfalen Hans-Ehrenberg-Gesellschaft _________________________________________________________________ Inhalt 2 Begrüßung Peter Scheffler | Superintendent 3 Theologischer Impuls Traugott Jähnichen | Professor für Christliche Gesellschaftslehre an der Ruhr-Uni Bochum 5 Preisverleihung Albert Henz | Vizepräsident der Evang. Kirche von Westfalen 6 Podiumsgespräch Antje Vollmer | Publizistin; Vizepräsidentin des Deutschen Bundestages a.D. Margot Käßmann | Prof. Dr. h.c. an der Ruhr-Universität Bochum Reinhard Mawick | Pressesprecher der Evang. Kirche in Deutschland Mitglieder aus Organisationen Ehemaliger Heimkinder BEGRÜSSUNG PETER SCHEFFLER | SUPERINTENDENT Am 1. Advent 1947 - Hans Ehrenberg war gerade erst aus dem englischen Exil nach Westfa- len zurückgekehrt; er war allerdings nicht von uns, seiner Kirche, zurückgerufen worden, auch seine Pfarrstelle in Bochum hat er nicht zurück erhalten - am 1. Advent 1947 schrieb Hans Ehrenberg in Bielefeld das Vorwort zu einem kleinen Buch. Jahrelang hatte er dieses Buch im Kopf getragen, jetzt, zwei Jahre nach dem Zusammen- bruch der Zivilisation schrieb er es zu Ende. Der Titel des Buches: "Vom Menschen". In diesem kleinen Buch findet sich folgende Erinnerung an das Jahr 1939 - jenes Jahr, in dem Ehrenberg mit seiner Familie nach England entkommen war: Damals, schreibt Ehrenberg, "am Anfang des Krieges wurde häufig betont, dass man kein Recht habe, sich Nazi-Deutschland gegenüber schlechtweg als den Repräsentanten des Christentums aufzuspielen. Man war sich weitgehend bewusst, dass es das Malen in Weiß und Schwarz nicht geben dürfe. Man konnte für sich selbst nur eine Art von Grau, näher zum Weiß oder näher zum Schwarz, und daher nur ein relatives Recht (…) in Anspruch nehmen. -

From Village Boy to Pastor

1 From Village Boy to Pastor CHILDHOOD, YOUTH, AND STUDENT DAYS Rüdlingen is a small farming village in the Canton of Schaffhausen, situated in northern Switzerland. The village is surrounded by a beauti- ful countryside only a few miles downriver from the Rhine Falls. Fertile fields extend toward the river, and steep vineyards rise behind the village. The Protestant church sits enthroned high above the village. Almost all of the villagers belonged to the Protestant faith. Adolf Keller was born and raised in one of Rüdlingen’s pretty half-timbered houses in 1872. He was the eldest child born to the village teacher Johann Georg Keller and his wife Margaretha, née Buchter. Three sisters and a brother were born to the Kellers after Adolf.SAMPLE A large fruit and vegetable garden contributed to the upkeep of the family. For six years, Adolf Keller attended the primary school classes taught by his father. The young boy’s performance so conspicuously excelled that of his sixty peers that the highly regarded village teacher decided not to award his son any grades. Occasionally, Keller senior involved his son in the teaching of classes. Both parents were ecclesiastically minded. Keller’s father took his Bible classes seriously. Adolf was required to learn by heart countless Bible verses. His mother ran the village Sunday School. She was a good storyteller. Unlike her more austere husband, Keller’s mother represented an emotional piety. She never missed attending the annual festival of the devout Basel Mission. 1 © 2013 The Lutterworth Press Adolf Keller The village of Rüdlingen and the Rhine (old picture postcard) The village pastor taught the young Keller Latin, and his daughter, who had traveled widely in Europe as a governess, taught him English and French. -

Aryan Jesus and the Kirchenkampf: an Examination of Protestantism Under the Third Reich Kevin Protzmann

Aryan Jesus and the Kirchenkampf: An Examination of Protestantism under the Third Reich Kevin Protzmann 2 Often unstated in the history of National Socialism is the role played by Protestantism. More often than not, Christian doctrine and institutions are seen as incongruous with Nazism. Accordingly, the Bekennende Kirche, or Confessing Church, receives a great deal of scholarly and popular attention as an example of Christian resistance to the National Socialist regime. Overlooked, however, were the Deutsche Christen, or German Christians. This division within Protestantism does more than highlight Christian opposition to Nazism; on balance, the same cultural shifts that allowed the rise of Adolf Hitler transformed many of the most fundamental aspects of Christianity. Even the Confessing Church was plagued with the influence of National Socialist thought. In this light, the German Christians largely overshadowed the Confessing Church in prominence and influence, and Protestantism under the Third Reich was more participatory than resistant to Nazi rule. Like the National Socialists, the Deutsche Christen, or German Christians, have their roots in the postwar Weimar Republic. The movement began with the intention of incorporating post-war nationalism with traditional Christian theology.1 The waves of nationalism brought about by the dissolution of the German Empire spread beyond political thought and into religious ideas. Protestant theologians feared that Christianity retained many elements that were not “German” enough, such as the Jewishness of Jesus, the canonicity of the Hebrew Bible, and the subservient nature of Christian ethics.2 These fears led to dialogues among the clergy and laity about the future and possible modification of Christian doctrine. -

Tbe Confessional Pastor and His Struggle the Rev

Tbe Confessional Pastor and His Struggle THE REv. HANS EHRENBERG, PH.D. ANY accounts of the Church conflict in Germany have M been published in this country; they have been either historical records or attempts to show the fundamental theological and political principles in-rolved. The present study has a different object, viz., to draw out the lessons of the conflict for the practical or pastoral life of the Church herself. This implies that our attempt must be to survey and sum up the facts as well as the truths of the struggle from the standpoint of one who is engaged in the struggle, i.e., to lay bare its hmer elements. Thus my essay is to present the German Church struggle in such a way that other churches see it as part and parcel of Church history and Church life in general and, hertte, also of their own. Following upon an ,introduction treating the fundamental aspect under which all churches should consider the German church conflict, I present in this essay what I may call the three dramatis persona of the "Church drama" :-the Confessional Pastor, the Heretic (the "German Christian"), and the Confessing Congregation. The study closes on the problem-still unsolved, in the Confessional Church, and the like in all churches--of a Confessional Church Government. Readers of this study are asked to forget, for the time being, all the special traditions of their own churchdom, if they are Anglican, or Nonconformist, or even German (of course pre-Hitler German). For the life and death struggle of a church concerns the "church within the church," and, hence, it is the l?truggle of the Church. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The case for theological ethics: an appreciation of Ernil Brunner and Reinhold Niebuhr as moral theologians Hamlyn, Eric Crawford How to cite: Hamlyn, Eric Crawford (1990) The case for theological ethics: an appreciation of Ernil Brunner and Reinhold Niebuhr as moral theologians, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/6271/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 THE CASE FOR THEOLOGICAL ETHICS An appreciation of Emil Brunner and Reinhold Niebuhr as moral theologians. Submitted by Eric Crawford Hamlyn Qualification for which it is submitted- M.A. University of Durham Department of Theology. 1990 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. CONTENTS -

1 Restoring Wholeness in an Age of Disorder: Europe's Long Spiritual

1 Restoring Wholeness in an Age of Disorder: Europe’s Long Spiritual Crisis and the Genealogy of Slavophile Religious Thought, 1835-1860 Patrick Lally Michelson September 2008 Many German writers, journalists, and scholars who witnessed the collapse of the Wilhelmine Reich in 1918 interpreted this event as the culmination of a protracted, European-wide crisis that had originated more than a century before in the breakdown of traditional political institutions, socioeconomic structures, moral values, and forms of epistemology, anthropology, and religiosity. For these intellectuals, as well as anyone else who sought to restore what they considered to be Germany’s spiritual vitality, one of the immediate tasks of the early Weimar years was to articulate authentic, viable modes of being and consciousness that would generate personal and communal wholeness in a society out of joint.1 Among the dizzying array of responses formulated at that time, several of the most provocative drew upon disparate, even antagonistic strands of Protestantism in the hope that the proper appropriation of Germany’s dominant confession could help the country overcome its long spiritual crisis.2 1 The Weimar Dilemma: Intellectuals in the Weimar Republic, edited by Anthony Phelan (Manchester University Press, 1985); Dagmar Barnouw, Weimar Intellectuals and the Threat of Modernity (Indiana University Press, 1988); and Intellektuelle in der Weimarer Republik, revised edition, edited by Wolfgang Bialas and Georg G. Iggers (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1997). For impressionistic accounts, see Egon Friedell, A Cultural History of the Modern Age: The Crisis of the European Soul from the Black Death to the World War, 3 vols., translated by Charles Francis Atkinson (New York: A. -

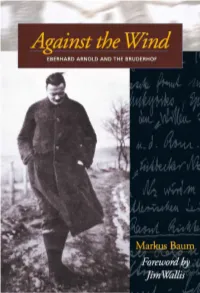

Against the Wind E B E R H a R D a R N O L D a N D T H E B R U D E R H O F

Against the Wind E B E R H A R D A R N O L D A N D T H E B R U D E R H O F Markus Baum Foreword by Jim Wallis Original Title: Stein des Anstosses: Eberhard Arnold 1883–1935 / Markus Baum ©1996 Markus Baum Translated by Eileen Robertshaw Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com Copyright © 2015, 1998 by Plough Publishing House All rights reserved Print ISBN: 978-0-87486-953-8 Epub ISBN: 978-0-87486-757-2 Mobi ISBN: 978-0-87486-758-9 Pdf ISBN: 978-0-87486-759-6 The photographs on pages 95, 96, and 98 have been reprinted by permission of Archiv der deutschen Jugendbewegung, Burg Ludwigstein. The photographs on pages 80 and 217 have been reprinted by permission of Archive Photos, New York. Contents Contents—iv Foreword—ix Preface—xi CHAPTER ONE 1 Origins—1 Parental Influence—2 Teenage Antics—4 A Disappointing Confirmation—5 Diversions—6 Decisive Weeks—6 Dedication—7 Initial Consequences—8 A Widening Rift—9 Missionary Zeal—10 The Salvation Army—10 Introduction to the Anabaptists—12 Time Out—13 CHAPTER TWO 14 Without Conviction—14 The Student Christian Movement—14 Halle—16 The Silesian Seminary—18 Growing Responsibility in the SCM—18 Bernhard Kühn and the EvangelicalAlliance Magazine—20 At First Sight—21 Against the Wind Harmony from the Outset—23 Courtship and Engagement—24 CHAPTER THREE 25 Love Letters—25 The Issue of Baptism—26 Breaking with the State Church—29 Exasperated Parents—30 Separation—31 Fundamental Disagreements among SCM Leaders—32 The Pentecostal Movement Begins—33 -

HTS 63 4 KRITZINGER.Tambach REVISED.AUTHOR

“The Christian in society”: Reading Barth’s Tambach lecture (1919) in its German context J N J Kritzinger Department of Christian Spirituality, Church History and Missiology University of South Africa Abstract This article analyses Karl Barth’s 1919 Tambach lecture on “The Christian in society” in the context of post World War I Europe. After describing Barth’s early life and his move away from liberal theology, the five sections of the Tambach lecture are analysed. Barth’s early dialectical theology focussed on: Neither secularising Christ nor clericalising society; Entering God’s movement in society; Saying Yes to the world as creation (regnum naturae) ; Saying No to evil in society (regnum gratiae) ; respecting God’s reign as beyond our attempts (regnum gloriae) . 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The approach of this paper This article should be read together with the one following it, since the two papers were conceived and born together. Rev B B Senokoane and I made a joint presentation to the conference on “Reading Karl Barth in South Africa today,” which was held in Pretoria on 10-11 August 2006. In the subsequent reworking of the material for publication, it became two articles. This article analyses the 1919 Tambach lecture of Karl Barth in its post World War I German context, to get a sense of the young Barth’s theological method and commitment. The second article uses Barth’s approach, as exhibited in that lecture, to theologise in South Africa, stepping into his shoes and “doing a Tambach” today. The first move is an exercise in historical interpretation and the second in contemporary imagination.