Herder, Kollár, and the Origins of Slavic Ethnography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAUSES of WORLD WAR I Objective: Analyze the Causes of World War I

CAUSES of WORLD WAR I Objective: Analyze the causes of World War I. Do Now: What are some holidays during which people celebrate pride in their national heritage? Causes of World War I - MANIA M ilitarism – policy of building up strong military forces to prepare for war Alliances - agreements between nations to aid and protect one another ationalism – pride in or devotion to one’s Ncountry I mperialism – when one country takes over another country economically and politically Assassination – murder of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand Causes of WWI - Militarism Total Defense Expenditures for the Great Powers [Ger., A-H, It., Fr., Br., Rus.] in millions of £s (British pounds). 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1914 94 130 154 268 289 398 1910-1914 Increase in Defense Expenditures France 10% Britain 13% Russia 39% Germany 73% Causes of WWI - Alliances Triple Entente: Triple Alliance: Great Britain Germany France Austria-Hungary Russia Italy Causes of WWI - Nationalism Causes of WWI - Nationalism Pan-Germanism - movement to unify the people of all German speaking countries Germanic Countries Austria * Luxembourg Belgium Netherlands Denmark Norway Iceland Sweden Germany * Switzerland * Liechtenstein United * Kingdom * = German speaking country Causes of WWI - Nationalism Pan-Slavism - movement to unify all of the Slavic people Imperialism: European conquest of Africa Causes of WWI - Imperialism Causes of WWI - Imperialism The “Spark” Causes of WWI - Assassination Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand visited the city of Sarajevo in Bosnia – a country that was under the control of Austria. Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Duchess Sophie in Sarajevo, Bosnia, on June 28th, 1914. Causes of WWI - Assassination Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife were killed in Bosnia by a Serbian nationalist who believed that Bosnia should belong to Serbia. -

A Cape of Asia: Essays on European History

A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 1 a cape of asia A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 2 A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 3 A Cape of Asia essays on european history Henk Wesseling leiden university press A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 4 Cover design and lay-out: Sander Pinkse Boekproductie, Amsterdam isbn 978 90 8728 128 1 e-isbn 978 94 0060 0461 nur 680 / 686 © H. Wesseling / Leiden University Press, 2011 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 5 Europe is a small cape of Asia paul valéry A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 6 For Arnold Burgen A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 7 Contents Preface and Introduction 9 europe and the wider world Globalization: A Historical Perspective 17 Rich and Poor: Early and Later 23 The Expansion of Europe and the Development of Science and Technology 28 Imperialism 35 Changing Views on Empire and Imperialism 46 Some Reflections on the History of the Partition -

Helmut Walser Smith, "Nation and Nationalism"

Smith, H. Nation and Nationalism pp. 230-255 Jonathan Sperber., (2004) Germany, 1800-1870, Oxford: Oxford University Press Staff and students of University of Warwick are reminded that copyright subsists in this extract and the work from which it was taken. This Digital Copy has been made under the terms of a CLA licence which allows you to: • access and download a copy; • print out a copy; Please note that this material is for use ONLY by students registered on the course of study as stated in the section below. All other staff and students are only entitled to browse the material and should not download and/or print out a copy. This Digital Copy and any digital or printed copy supplied to or made by you under the terms of this Licence are for use in connection with this Course of Study. You may retain such copies after the end of the course, but strictly for your own personal use. All copies (including electronic copies) shall include this Copyright Notice and shall be destroyed and/or deleted if and when required by University of Warwick. Except as provided for by copyright law, no further copying, storage or distribution (including by e-mail) is permitted without the consent of the copyright holder. The author (which term includes artists and other visual creators) has moral rights in the work and neither staff nor students may cause, or permit, the distortion, mutilation or other modification of the work, or any other derogatory treatment of it, which would be prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the author. -

The German Influence on the Life and Thought of W.E.B. Dubois. Michaela C

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2001 The German influence on the life and thought of W.E.B. DuBois. Michaela C. Orizu University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Orizu, Michaela C., "The German influence on the life and thought of W.E.B. DuBois." (2001). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2566. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2566 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE GERMAN INFLUENCE ON THE LIFE AND THOUGHT OF W. E. B. DU BOIS A Thesis Presented by MICHAELA C. ORIZU Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 2001 Political Science THE GERMAN INFLUENCE ON THE LIE AND THOUGHT OF W. E. B. DU BOIS A Master’s Thesis Presented by MICHAELA C. ORIZU Approved as to style and content by; Dean Robinson, Chair t William Strickland, Member / Jerome Mileur, Member ad. Department of Political Science ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I like would to thank my advisors William Strickland and Dean Robinson for their guidance, insight and patient support during this project as well as for the inspiring classes they offered. Many thanks also to Prof. Jerome Mileur for taking interest in my work and joining my thesis committee at such short notice. -

Explaining Irredentism: the Case of Hungary and Its Transborder Minorities in Romania and Slovakia

Explaining irredentism: the case of Hungary and its transborder minorities in Romania and Slovakia by Julianna Christa Elisabeth Fuzesi A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Government London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2006 1 UMI Number: U615886 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615886 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is entirely my own. Signature Date ....... 2 UNIVERSITY OF LONDON Abstract of Thesis Author (full names) ..Julianna Christa Elisabeth Fiizesi...................................................................... Title of thesis ..Explaining irredentism: the case of Hungary and its transborder minorities in Romania and Slovakia............................................................................................................................. ....................................................................................... Degree..PhD in Government............... This thesis seeks to explain irredentism by identifying the set of variables that determine its occurrence. To do so it provides the necessary definition and comparative analytical framework, both lacking so far, and thus establishes irredentism as a field of study in its own right. The thesis develops a multi-variate explanatory model that is generalisable yet succinct. -

The Franco-Prussian War: Its Impact on France and Germany, 1870-1914

The Franco-Prussian War: Its Impact on France and Germany, 1870-1914 Emily Murray Professor Goldberg History Honors Thesis April 11, 2016 1 Historian Niall Ferguson introduced his seminal work on the twentieth century by posing the question “Megalomaniacs may order men to invade Russia, but why do the men obey?”1 He then sought to answer this question over the course of the text. Unfortunately, his analysis focused on too late a period. In reality, the cultural and political conditions that fostered unparalleled levels of bloodshed in the twentieth century began before 1900. The 1870 Franco- Prussian War and the years that surrounded it were the more pertinent catalyst. This event initiated the environment and experiences that catapulted Europe into the previously unimaginable events of the twentieth century. Individuals obey orders, despite the dictates of reason or personal well-being, because personal experiences unite them into a group of unconscious or emotionally motivated actors. The Franco-Prussian War is an example of how places, events, and sentiments can create a unique sense of collective identity that drives seemingly irrational behavior. It happened in both France and Germany. These identities would become the cultural and political foundations that changed the world in the tumultuous twentieth century. The political and cultural development of Europe is complex and highly interconnected, making helpful insights into specific events difficult. It is hard to distinguish where one era of history begins or ends. It is a challenge to separate the inherently complicated systems of national and ethnic identities defined by blood, borders, and collective experience. -

Regionalism, Federalism and Nationalism in the German Empire Siegfried Weichlein

6 Regionalism, Federalism and Nationalism in the German Empire Siegfried Weichlein i{t•gions and regionalism had a great impact on developments in nineteenth ' ·t•ntury Germany. The century began with a genuine territorial revolution in Pebruary 1803 that ended the iridependent history of hundreds of regional states and brought their number down to 34. After several hundred years of rl'lative continuity this was a clear break with the past. Bringing the number t ,r German states down further to 27 and taking away much of their indepen dence with the unification of Germany in 1871 was then a comparatively small step. What had begun in the late eighteenth century- the dissoci ation of territory and political power- reached a certain climax in 1803. Early-modern small state particularism, nevertheless, had a Iasting impact on regionalism as well as nationalism. Deprived of their political power the old German states still fastered a sense of the 'federative nation' (föderative Nation). 1 Regional identity was therefore still a veritable cultural and political rorce which could support a call for federalism. Regions could be coextensive with a state, but also exist below the states and between them. A good example is the Palatinate. Since the late eighteenth century it belonged politically and administratively to Bavaria. Culturally and to a certain extent politically, however, representatives of the Palatinate kept their distance fram the capital Munich. In this the Palatinate did not stand alone. Many sub-state regionalisms explicitly or implicitly referred to their political borders before the French Revolution. Regions like Lower Franconia araund Würzburgor Westfalen araund Münster had been former bishoprics that had lost their political independence under Napoleon. -

This Led to the Event That Triggered World War I – the Assassination of Franz Ferdinand

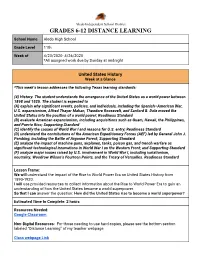

Aledo Independent School District GRADES 6-12 DISTANCE LEARNING School Name Aledo High School Grade Level 11th Week of 4/20/2020- 4/26/2020 *All assigned work due by Sunday at midnight United States History Week at a Glance *This week’s lesson addresses the following Texas learning standards: (4) History. The student understands the emergence of the United States as a world power between 1898 and 1920. The student is expected to (A) explain why significant events, policies, and individuals, including the Spanish–American War, U.S. expansionism, Alfred Thayer Mahan, Theodore Roosevelt, and Sanford B. Dole moved the United States into the position of a world power; Readiness Standard (B) evaluate American expansionism, including acquisitions such as Guam, Hawaii, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico; Supporting Standard (C) identify the causes of World War I and reasons for U.S. entry; Readiness Standard (D) understand the contributions of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) led by General John J. Pershing, including the Battle of Argonne Forest; Supporting Standard (E) analyze the impact of machine guns, airplanes, tanks, poison gas, and trench warfare as significant technological innovations in World War I on the Western Front; and Supporting Standard (F) analyze major issues raised by U.S. involvement in World War I, including isolationism, neutrality, Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, and the Treaty of Versailles. Readiness Standard Lesson Frame: We will understand the impact of the Rise to World Power Era on United States History from 1890-1920. I will use provided resources to collect information about the Rise to World Power Era to gain an understanding of how the United States became a world superpower. -

Resolving Puerto Rico's Political Status

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Fordham University School of Law Fordham International Law Journal Volume 33, Issue 3 2009 Article 6 An Unsatisfactory Case of Self-Determination: Resolving Puerto Rico’s Political Status Lani E. Medina∗ ∗ Copyright c 2009 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj An Unsatisfactory Case of Self-Determination: Resolving Puerto Rico’s Political Status Lani E. Medina Abstract In the case of Puerto Rico, the exercise of self-determination has raised, and continues to raise, particularly difficult questions that have not been adequately addressed. Indeed, as legal scholars Gary Lawson and Robert Sloane observe in a recent article, “[t]he profound issues raised by the domestic and international legal status of Puerto Rico need to be faced and resolved.” Accord- ingly, this Note focuses on the application of the principle of self-determination to the people of Puerto Rico. Part I provides an overview of the development of the principle of self-determination in international law and Puerto Rico’s commonwealth status. Part II provides background infor- mation on the political status debate in Puerto Rico and focuses on three key issues that arise in the context of self-determination in Puerto Rico. Part III explains why Puerto Rico’s political status needs to be resolved and how the process of self-determination should proceed in Puerto Rico. Ultimately, this Note contends that the people of Puerto Rico have yet to fully exercise their right to self-determination. -

British Identity and the German Other William F

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2012 British identity and the German other William F. Bertolette Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Bertolette, William F., "British identity and the German other" (2012). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2726. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2726 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. BRITISH IDENTITY AND THE GERMAN OTHER A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by William F. Bertolette B.A., California State University at Hayward, 1975 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2004 May 2012 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the LSU History Department for supporting the completion of this work. I also wish to express my gratitude for the instructive guidance of my thesis committee: Drs. David F. Lindenfeld, Victor L. Stater and Meredith Veldman. Dr. Veldman deserves a special thanks for her editorial insights -

The Consequences of Early Colonial Policies on East African Economic and Political Integration

The Consequences of Early Colonial Policies on East African Economic and Political Integration The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Battani, Matthew. 2020. The Consequences of Early Colonial Policies on East African Economic and Political Integration. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37365415 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Consequences of Early Colonial Policies on the East African Economic and Political Integration Matthew Lee Battani A Thesis in the Field of International Relations for the Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2020 © 2020 Matthew Lee Battani Abstract Twentieth-century economic integration in East Africa dates back to European initiates in the 1880s. Those policies culminated in the formation of the first East African Community (EAC I) in 1967 between Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. The EAC was built on a foundation of integrative polices started by Britain and Germany, who began formal colonization in 1885 as a result of the General Act of the Berlin Conference during the Scramble for Africa. While early colonial polices did foster greater integration, they were limited in important ways. Early colonial integration was bi-lateral in nature and facilitated European monopolies. Early colonial policies did not foster broad economic integration between East Africa’s neighbors or the wider world economy. -

Dokumentationen Zum Sächsischen Bergbau

Dokumentationen zum Sächsischen Bergbau Reihe 2: Kohle Gewinnung und Verarbeitung in Sachsen Band 1: Geologie und Geschichte des Steinkohlen- bergbaus von Hainichen Recherchestand Dezember 2015 Autor: G. Mühlmann Herausgegeben vom Bergbauverein Hülfe des Herrn, Alte Silberfundgrube e. V. Merzdorf / Biensdorf Biensdorf, Dezember 2016 Unbekannter Bergbau Dokumentationen zum sächsischen Bergbau, Kohle – Band 1 Reihe 2: Zum Steinkohlenbergbau: Band 1: Zur Geologie und Geschichte des Steinkohlen- bergbaus von Hainichen Inhalt 1. Zum Geleit............................................................................................................... 2 2. Zur Geologie des nordöstlichsten Teils des Erzgebirge Beckens ............................ 4 2.1 Die Mulde von Chemnitz-Hainichen oder das Karbon von Hainichen-Ebersdorf und Borna bei Chemnitz ......................................................................................... 4 2.2 Die Hainichen-Schichten, die Hainichen-Subgruppe oder die Frühmolassen von Borna-Hainichen ..................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Die Steinkohlenlagerstätte von Hainichen- Berthelsdorf oder nach Geinitz: „Das Hainichener Kohlenbassin“ ................................................................................... 16 2.4 Die Steinkohlenlagerstätte von Chemnitz, Borna und Ebersdorf oder nach Geinitz: „Das Ebersdorfer Kohlenbassin“ ........................................................................... 22 2.5 Weitere Bodenschätze in der