Resolving Puerto Rico's Political Status

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Cape of Asia: Essays on European History

A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 1 a cape of asia A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 2 A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 3 A Cape of Asia essays on european history Henk Wesseling leiden university press A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 4 Cover design and lay-out: Sander Pinkse Boekproductie, Amsterdam isbn 978 90 8728 128 1 e-isbn 978 94 0060 0461 nur 680 / 686 © H. Wesseling / Leiden University Press, 2011 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 5 Europe is a small cape of Asia paul valéry A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 6 For Arnold Burgen A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 7 Contents Preface and Introduction 9 europe and the wider world Globalization: A Historical Perspective 17 Rich and Poor: Early and Later 23 The Expansion of Europe and the Development of Science and Technology 28 Imperialism 35 Changing Views on Empire and Imperialism 46 Some Reflections on the History of the Partition -

Explaining Irredentism: the Case of Hungary and Its Transborder Minorities in Romania and Slovakia

Explaining irredentism: the case of Hungary and its transborder minorities in Romania and Slovakia by Julianna Christa Elisabeth Fuzesi A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Government London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2006 1 UMI Number: U615886 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615886 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is entirely my own. Signature Date ....... 2 UNIVERSITY OF LONDON Abstract of Thesis Author (full names) ..Julianna Christa Elisabeth Fiizesi...................................................................... Title of thesis ..Explaining irredentism: the case of Hungary and its transborder minorities in Romania and Slovakia............................................................................................................................. ....................................................................................... Degree..PhD in Government............... This thesis seeks to explain irredentism by identifying the set of variables that determine its occurrence. To do so it provides the necessary definition and comparative analytical framework, both lacking so far, and thus establishes irredentism as a field of study in its own right. The thesis develops a multi-variate explanatory model that is generalisable yet succinct. -

This Led to the Event That Triggered World War I – the Assassination of Franz Ferdinand

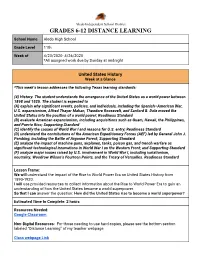

Aledo Independent School District GRADES 6-12 DISTANCE LEARNING School Name Aledo High School Grade Level 11th Week of 4/20/2020- 4/26/2020 *All assigned work due by Sunday at midnight United States History Week at a Glance *This week’s lesson addresses the following Texas learning standards: (4) History. The student understands the emergence of the United States as a world power between 1898 and 1920. The student is expected to (A) explain why significant events, policies, and individuals, including the Spanish–American War, U.S. expansionism, Alfred Thayer Mahan, Theodore Roosevelt, and Sanford B. Dole moved the United States into the position of a world power; Readiness Standard (B) evaluate American expansionism, including acquisitions such as Guam, Hawaii, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico; Supporting Standard (C) identify the causes of World War I and reasons for U.S. entry; Readiness Standard (D) understand the contributions of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) led by General John J. Pershing, including the Battle of Argonne Forest; Supporting Standard (E) analyze the impact of machine guns, airplanes, tanks, poison gas, and trench warfare as significant technological innovations in World War I on the Western Front; and Supporting Standard (F) analyze major issues raised by U.S. involvement in World War I, including isolationism, neutrality, Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, and the Treaty of Versailles. Readiness Standard Lesson Frame: We will understand the impact of the Rise to World Power Era on United States History from 1890-1920. I will use provided resources to collect information about the Rise to World Power Era to gain an understanding of how the United States became a world superpower. -

The Consequences of Early Colonial Policies on East African Economic and Political Integration

The Consequences of Early Colonial Policies on East African Economic and Political Integration The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Battani, Matthew. 2020. The Consequences of Early Colonial Policies on East African Economic and Political Integration. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37365415 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Consequences of Early Colonial Policies on the East African Economic and Political Integration Matthew Lee Battani A Thesis in the Field of International Relations for the Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2020 © 2020 Matthew Lee Battani Abstract Twentieth-century economic integration in East Africa dates back to European initiates in the 1880s. Those policies culminated in the formation of the first East African Community (EAC I) in 1967 between Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. The EAC was built on a foundation of integrative polices started by Britain and Germany, who began formal colonization in 1885 as a result of the General Act of the Berlin Conference during the Scramble for Africa. While early colonial polices did foster greater integration, they were limited in important ways. Early colonial integration was bi-lateral in nature and facilitated European monopolies. Early colonial policies did not foster broad economic integration between East Africa’s neighbors or the wider world economy. -

Eurasian Politics and Society

Eurasian Politics and Society Eurasian Politics and Society: Issues and Challenges Edited by Özgür Tüfekçi, Hüsrev Tabak and Erman Akıllı Eurasian Politics and Society: Issues and Challenges Edited by Özgür Tüfekçi, Hüsrev Tabak and Erman Akıllı This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Özgür Tüfekçi, Hüsrev Tabak, Erman Akıllı and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5511-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5511-2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Turkish Eurasianism: Roots and Discourses Özgür Tüfekçi Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 36 Moscow’s Sense of Eurasianism: Seeking after Central Asia but not wanting the Central Asian Mehmet Arslan Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 52 The European Union and the Integration of the Balkans and the Caucasus Didem Ekinci Chapter Four ............................................................................................. -

Chapter Fourteen: Westward Expansion C O Nt E Nt S 14.1 Introduction

Chapter Fourteen: Westward Expansion C o nt e nt s 14.1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 618 14.1.1 Learning Outcomes ..................................................................................... 618 14.2 WESTWARD EXPANSION AND MANIFEST DESTINY .........................................619 14.2.1Texas .......................................................................................................621 The Texas Revolution and the Lone Star Republic .................................................... 624 14.2.2Oregon.....................................................................................................625 14.2.3 The Election of 1844 ................................................................................... 627 14.2.4 The Mormon Trek ....................................................................................... 628 14.2.5 Before You Move On... ................................................................................ 629 Key Concepts ................................................................................................... 629 Test Yourself .................................................................................................... 630 14.3THE MEXICAN-AMERICAN WAR ..................................................................... 631 14.3.1 The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the Aftermath of the War ........................ 633 Technological Development and Manifest Destiny ................................................. -

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 Introduction he advent of Nazism in the 1920s and 1930s shocked many Europeans who believed that World War I had been fought to make the “world safe for democracy.” Indeed, TNazism was only one, although the most important, of a number of similar-looking fascist movements in Europe between World War I and World War II. While Nazism, like the others, owed much to the impact of World War I, it also needs to be viewed in the context of developments in Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. EUROPe IN THe NINeTeeNTH CeNTURY Many Europeans perceived the nineteenth century as an age of progress based on the growth of rationalism, secularism, and materialism. One English social philosopher claimed that progress was not an “accident, but a necessity,” which would enable humans to “become perfect.” By the end of the nineteenth century, however, there were voices who challenged these optimistic assumptions. They spoke of human irrationality and the need for violence to solve human problems. Nazism would later draw heavily upon this antirational mood and reject the rationalist and materialist views of progress. The major ideas that dominated European political life in the nineteenth cen- tury seemed to support the notion of progress. Liberalism professed belief in a con- stitutional state and the basic civil rights of every individual. Nazism would later reject liberalism and assert the rights of the state over individuals. Nationalism, predicated on the nation as the focus of people’s loyalty, became virtually a new religion for Europeans in the nineteenth century. -

Colonialism and Imperialism, 1450-1950 by Benedikt Stuchtey

Colonialism and Imperialism, 1450-1950 by Benedikt Stuchtey The colonial encirclement of the world is an integral component of European history from the Early Modern Period to the phase of decolonisation. Individual national and expansion histories referred to each other in varying degrees at dif- ferent times but often also reinforced each other. Transfer processes within Europe and in the colonies show that not only genuine colonial powers such as Spain and England, but also "latecomers" such as Germany participated in the historical process of colonial expansion with which Europe decisively shaped world history. In turn, this process also clearly shaped Europe itself. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Colonialism and Imperialism 3. Regions and periods 4. Forms 5. Outlook 6. Appendix 1. Literature 2. Notes Citation Introduction In world history, no continent has possessed so many different forms of colonies and none has so incomparably defined access to the world by means of a civilising mission as a secular programme as did modern Europe. When Spain and Portugal partitioned the world by signing the Treaty of Tordesillas (ᇄ Media Link #ab) on 7 June 1494, they declared a genuine European claim to hegemony. A similar claim was never staked out in this form by a world empire of Antiquity or a non-European colonial power in the modern period, such as Japan or the USA. The extraordinary continuity of Chi- nese colonialism or that of the Aztecs in Central America before the Spaniards arrived is indeed structurally comparable to modern European expansion. But similar to the Phoenician and the Roman empires, the phenomenon of expansion usually ended with colonisation and not in colonial development. -

The Pan-German League at the End of the 19Th Century1

The Pan-German League 1 OPEN at the End of the 19th Century ACCESS Martin Urban Over the course of the 19th century, a feeling of national unity began to gradually de- velop within Germany. The real triumph of the German nation was the successful Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871, which subsequently, thanks to Prussian Min- ister President Otto von Bismarck, led to the unification of the German Empire on 18 January 1871.1 For the vast majority of Germans, the establishment of the Empire was a deeply emotional issue. The experience and feeling of pride of a whole gener- ation set the foundations for a strong modern German nationalism which over the course of subsequent years continued to develop dynamically. Despite the euphoria, here and there voices were heard criticising Bismarck’s little-Germany unification concept; the new situation was not enough for certain nationalist groups. They im- agined a much more ambitious process for unifying all Germans (e.g. including those in the Habsburg Monarchy, but often also those who would not actually consider themselves German) within one state, i.e. the realisation of a so-called Greater Ger- many solution. Later on, there were even some who would be dissatisfied even with that. As such, the aggressive ideology of Pan-Germanism was slowly born, finding an institutional form in the later Pan-German League (Alldeutscher Verband). The objective of this study is not to give a definition of the Pan-Germanism term, nor to ascertain the causes or reasons that this phenomenon is closely linked to the history of Germany and the German nation.2 The task of this paper is to give an overview of the development of the Pan-German League from the beginnings of the organisation until the end of Ernst Hasse’s presidency of the league in 1908. -

The Effects of Imperialism on the US: 1899-1902

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2016 Apr 28th, 9:00 AM - 10:15 AM The Effects of Imperialism on the US: 1899-1902 Logan Marek Lakeridge High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the American Politics Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Marek, Logan, "The Effects of Imperialism on the US: 1899-1902" (2016). Young Historians Conference. 5. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2016/oralpres/5 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THE EFFECTS OF IMPERIALISM ON THE US: 1899-1902 The Philippine-American war was a conflict that brought the morality of traditional American values into question. The United States stepped into the world of geopolitics and colonialism with the annexation and subjugation of the Philippines. In 1898 the United States declared war on Spain in what became the Spanish-American War. The conflict was short and the United States came out victorious. The United States entered the conflict in order to free the Cubans from what it saw as oppression by the Spaniards. A consequence of the conflict was the United States’ entrance into the kingdom of colonial powers. It gained territories in the Caribbean and Pacific, with Puerto Rico and Cuba becoming protectorates and the Philippines becoming a United States colony. -

Herder's Ideas and the Pan-Slavism: a Conceptual-Historical Approach

DušAN LJUBOJA Herder’s Ideas and the Pan-Slavism: A Conceptual-Historical Approach Pro&Contra 2 No. 2 (2018) 67-85. DOI: 10.33033/pc.2018.2.67 HERDER’S IDEAS AND THE PAN-SLAVISM: A CONCEPTUAL-HISTORICAL APPROACH 69 Abstract The impact of Johann Gottfried Herder on the Slavic intellectuals of the Nineteenth century is well-known among researchers in the fields of history, linguistics and anthropology. His “prophecy” about the future of the Slavs influenced the writings of Ján Kollár and Pavel J. Šafárik, among others, writers who became some of the most prominent figures of the Pan-Slavic cultural movement of the first half of the Nineteenth century. Their influence on Serbian intellectuals, especially on those living in Buda and Pest, was visible. However, this “Herderian prophecy” also came to the Serbian readership indirectly, mostly through the efforts of scholars like Šafárik. The prediction of a bright future for all Slavs was introduced either as original contributions of the aforementioned scholars, or as the translated excerpts of their most famous works. One of the themes presented in the Serbian periodicals was the notion of the “enslavement” of Slavs by Germans and Hungarians in the Early Middle Ages. In order to better understand the meaning of “Herder’s prophecy” and its reception and adaptation by the aforementioned Pan-Slavists, this paper utilizes Reinhart Koselleck’s writings on conceptual history. Keywords: Johann G. Herder, Pan-Slavism, conceptual history, Ján Kollár, Pavel J. Šafárik, Serbian periodicals Introduction The work Outlines of a Philosophy of the History of Man by Johann Gottfried Herder was highly influential on what later became the Pan-Slavic movement, especially in the decades prior to the revolutions of 1848. -

Hungarian War Aims During WWI: Between Expansionism and Separatism Aliaksandr Piahanau

Hungarian War Aims During WWI: Between Expansionism and Separatism Aliaksandr Piahanau To cite this version: Aliaksandr Piahanau. Hungarian War Aims During WWI: Between Expansionism and Separatism. Central European Papers, Silesian University in Opava (Czech Republic), 2014, 2 (2), pp. 95-107. halshs-01261461 HAL Id: halshs-01261461 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01261461 Submitted on 31 Jan 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. CENTRAL EUROPEAN PAPERS 2014 / II / 2 95 Hungarian War Aims During WWI: Between Expansionism and Separatism Aliaksandr PIAHANAU Беларускі дзяржаўны ўніверсітэт, гістарычны факультэт, кафедра гісторыі паўдневых і заходніх славян Belarusian State University, Faculty of History, Department of Southern and Western Slav’s History Vul. Chyrvonaarmejskaja 6, 220030 Minsk, Belarus Université Paris Diderot – Paris 7, Laboratoire « Identités – Cultures – Territoires » University Paris Diderot – Paris 7, Laboratory « Identities – Cultures – Territories » 8, Rue Albert Einstein, 75205 Paris cedex 13, France [email protected] O ¡ of the central elements of modern Hungarian national identity – the so-called “Trianon trauma” – is directly related to the events of the Great War 1914–1918. The war ended by a drastic reduction of the Hungarian territory (from 325,000 km 2 to 93,000) and as a consequence, the formation of large ethnic Magyar communities on the near border regions (around 3 millions).