The Defence White Paper 17 SEPTEMBER 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Limited Capacity of Management to Rescue UK Defence Policy: a Review and a Word of Caution

The limited capacity of management to rescue UK defence policy: a review and a word of caution TREVOR TAYLOR* The three dimensions of defence In terms of press coverage and political debate, the story of British defence since the end of the Cold War has been marked by three themes: policy (direction and review), management (shortcomings and initiatives), and military opera- tions, although academic studies and courses tend to neglect the management domain.1 In principle, these three elements should be closely linked, with policy defining the evolving state of the world and constraining the direction of the country’s military response, management delivering the leadership, organiza- tion and coordination to build the forces to enable the policy to be implemented, and military operations being undertaken in line with the policy guidance and management preparations made. In practice, however, there have been significant disjunctions between the operations mounted and the policy and management. Military operations launched since 1990 have all been something of a surprise, most of them requiring significant extra funding to be obtained through Urgent Operational Requirements (UORs) to enhance and modify British capabilities before the operations could begin. The concept of Force Elements at Readiness (FE@R), the key output of the mainstream defence budget, came to be recognized in the MoD as of only limited utility unless consideration of the specific attributes of a particular adversary, the physical environment of the envisaged operation and the contribution of allies were also included in the equation. Also, in some cases a policy decision associated with specific changes in military posture was significantly undermined or even contradicted by events. -

Towards a Tier One Royal Air Force

TOWARDS A TIER ONE ROYAL AIR FORCE MARK GUNZINGER JACOB COHN LUKAS AUTENRIED RYAN BOONE TOWARDS A TIER ONE ROYAL AIR FORCE MARK GUNZINGER JACOB COHN LUKAS AUTENRIED RYAN BOONE 2019 ABOUT THE CENTER FOR STRATEGIC AND BUDGETARY ASSESSMENTS (CSBA) The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments is an independent, nonpartisan policy research institute established to promote innovative thinking and debate about national security strategy and investment options. CSBA’s analysis focuses on key questions related to existing and emerging threats to U.S. national security, and its goal is to enable policymakers to make informed decisions on matters of strategy, security policy, and resource allocation. ©2019 Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. All rights reserved. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Mark Gunzinger is a Senior Fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. Mr. Gunzinger has served as the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Forces, Transformation and Resources. A retired Air Force Colonel and Command Pilot, he joined the Office of the Secretary of Defense in 2004 and was appointed to the Senior Executive Service and served as Principal Director of the Department’s central staff for the 2005–2006 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR). He served as Director for Defense Transformation, Force Planning and Resources on the National Security Council staff. Mr. Gunzinger holds an M.S. in National Security Strategy from the National War College, a Master of Airpower Art and Science degree from the School of Advanced Air and Space Studies, an M.P.A. from Central Michigan University, and a B.S. in Chemistry from the United States Air Force Academy. -

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 35

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 35 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First published in the UK in 2005 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Northmoor OX29 5UH 3 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-Marshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman Group Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary Group Captain K J Dearman Membership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol AMRAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA Members Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA *J S Cox Esq BA MA *Dr M A Fopp MA FMA FIMgt *Group Captain C J Finn MPhil RAF *Wing Commander W A D Carter RAF Wing Commander C Cummings Editor & Publications Wing Commander C G Jefford MBE BA Manager *Ex Officio 4 CONTENTS THE EARLY DAYS by Wg Cdr Larry O’Hara 8 SUPPLY COMES OF AGE by Wg Cdr Colin Cummings 19 SUPPLY: TWO WARTIME EXAMPLES by Air Cdre Henry 34 Probert EXPLOSIVES by Wg Cdr Mike Wooldridge 41 NUCLEAR WEAPONS AND No 94 MU, RAF BARNHAM by 54 Air Cdre Mike Allisstone -

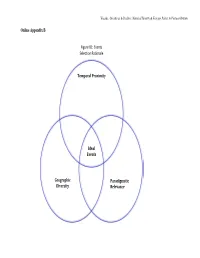

Online Appendix B Figure B1: Events Selection Rationale Temporal

Vucetic, Greatness & Decline: National Identity & Foreign Policy in Postwar Britain Online Appendix B Figure B1: Events Selection Rationale Temporal Proximity Ideal Events Geographic Paradigmatic Diversity Relevance Vucetic, Greatness & Decline: National Identity & Foreign Policy in Postwar Britain Online Appendix B—Postwar Defence Reviews in Chronological Order Sandys, D. (1957). Statement on defence, 1957 . London: Ministry of Defence. Retrieved on 8 April 2017 from http://filestore.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pdfs/small/cab-129-86-c-57-69-19.pdf Healey, D. (1966). Defence review: The statement on the defence estimates . London: Ministry of Defence. Retrieved on 8 April 2017 from http://filestore.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pdfs/small/cab-129-124-c-33.pdf Mason, R. (1975). Statement on the defence estimates London: Ministry of Defence. Retrieved on 8 April 2017 from http://filestore.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pdfs/small/cab-129-181-c-21.pdf Nott, J. (1981). The United Kingdom defence programme: The way forward. London: Ministry of Defence. Retrieved on 8 April 2017 from http://fc95d419f4478b3b6e5f-3f71d0fe2b653c4f00f32175760e96e7.r87.cf1.rackcdn.com/991284B4011C44C9AEB423DA04A7D54B.pdf King, T. (1990). Defence (Options for change). London: Ministry of Defence. Retrieved on 8 April 2017 from https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1990/jul/25/defence-options-for-change Rifkind, M. (1994). Front line first. London: Ministry of Defence. Retrieved on 8 April 2017 from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm199394/cmhansrd/1994-07-14/Debate-1.html Hoon, G. (2002). The strategic defence review: A new chapter. London: Ministry of Defence. Retrieved on 8 April 2017 from http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20090805012836/http://www.mod.uk/DefenceInternet/AboutDefence/CorporatePublications/ PolicyStrategyandPlanning/StrategicDefenceReviewANewChaptercm5566.htm Hoon, G. -

Andrew Dorman Michael D. Kandiah and Gillian Staerck ICBH Witness

edited by Andrew Dorman Michael D. Kandiah and Gillian Staerck ICBH Witness Seminar Programme The Nott Review The ICBH is grateful to the Ministry of Defence for help with the costs of producing and editing this seminar for publication The analysis, opinions and conclusions expressed or implied in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the JSCSC, the UK Ministry of Defence, any other Government agency or the ICBH. ICBH Witness Seminar Programme Programme Director: Dr Michael D. Kandiah © Institute of Contemporary British History, 2002 All rights reserved. This material is made available for use for personal research and study. We give per- mission for the entire files to be downloaded to your computer for such personal use only. For reproduction or further distribution of all or part of the file (except as constitutes fair dealing), permission must be sought from ICBH. Published by Institute of Contemporary British History Institute of Historical Research School of Advanced Study University of London Malet St London WC1E 7HU ISBN: 1 871348 72 2 The Nott Review (Cmnd 8288, The UK Defence Programme: The Way Forward) Held 20 June 2001, 2 p.m. – 6 p.m. Joint Services Command and Staff College Watchfield (near Swindon), Wiltshire Chaired by Geoffrey Till Paper by Andrew Dorman Seminar edited by Andrew Dorman, Michael D. Kandiah and Gillian Staerck Seminar organised by ICBH in conjunction with Defence Studies, King’s College London, and the Joint Service Command and Staff College, Ministry of -

A Brief Guide to Previous British Defence Reviews

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07313, 19 November 2015 A brief guide to previous By Nigel Walker British defence reviews Claire Mills Inside: 1. Background 2. Post-World War Two 3. Sandys Review – 1957 4. Healey Reviews – 1965-1968 5. Mason Review – 1974-1975 6. Nott Review – 1981 7. Options for Change – 1990 8. The Defence Costs Study – 1994 9. Strategic Defence Review and the SDR New Chapter – 1998 and 2002 10. Defence White Paper – 2003- 2004 11. Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR) – 2010 12. Developments since the 2010 SDSR www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 07313, 19 November 2015 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Background 4 2. Post-World War Two 6 3. Sandys Review – 1957 7 4. Healey Reviews – 1965-1968 9 5. Mason Review – 1974-1975 10 6. Nott Review – 1981 12 7. Options for Change – 1990 14 8. The Defence Costs Study – 1994 17 9. Strategic Defence Review and the SDR New Chapter – 1998 and 2002 19 9.1 SDR New Chapter 21 10. Defence White Paper – 2003-2004 22 11. Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR) – 2010 27 11.1 National security tasks and planning guidelines 27 11.2 Alliances and partnerships 28 11.3 Defence and the armed forces 28 12. Developments since the 2010 SDSR 30 12.1 Personnel 30 12.2 Equipment 30 12.3 Defence spending 30 12.4 Operational deployments 31 12.5 Reserves 31 12.6 Defence reform 32 Cover page image copyright: MOD Sign by UK Ministry of Defence. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 / image cropped. -

HJS ''Global Britain' and the Future of the British Armed Force

HJS '‘Global Britain’ and the Future of the British Armed Forces' Report_HJS '‘Global Britain’ and the Future of the British Armed Forces' Report.qxd 15/11/2017 12:57 Page 1 ‘Global Britain’ and the Future of the British Armed Forces James Rogers HJS '‘Global Britain’ and the Future of the British Armed Forces' Report_HJS '‘Global Britain’ and the Future of the British Armed Forces' Report.qxd 15/11/2017 12:57 Page 2 Published in 2017 by The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society Millbank Tower 21-24 Millbank London SW1P 4QP Registered charity no. 1140489 Tel: +44 (0)20 7340 4520 www.henryjacksonsociety.org © The Henry Jackson Society, 2017 All rights reserved The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and are not necessarily indicative of those of The Henry Jackson Society or its Trustees. Titl e: “‘Global Britain’ and the Future of the British Armed Forces” By: James Rogers Front cover: HMS Bulwark, as part of the Joint Expeditionary Force (Maritime) Task Group, cruising through the Suez Canal, October 2016. Image credit: L(Phot) Paul Hall, FRPU (E) Royal Navy, Crown Copyright. ISBN: 978-1-909035-38-6 £5.95 where sold HJS '‘Global Britain’ and the Future of the British Armed Forces' Report_HJS '‘Global Britain’ and the Future of the British Armed Forces' Report.qxd 15/11/2017 12:57 Page 3 ‘Global Britain’ and the Future of the British Armed Forces James Rogers Global Britain Programme www.henryjacksonsociety.org Report No. 2017/3 HJS '‘Global Britain’ and the Future of the British Armed Forces' Report_HJS '‘Global Britain’ and the Future of the British Armed Forces' Report.qxd 15/11/2017 12:57 Page 4 ‘GLOBAL BRITAIN’ AND THE FUTURE OF THE BRITISH ARMED FORCES Our security remains involved with that of our continental neighbours: for the dominance of the European landmass by an alien and hostile power would make almost impossible the maintenance of our national independence, to say nothing of our capacity to maintain a defensive system to protect any extra-European interests we may retain. -

Ministry of Defence Annual Report and Accounts 2007-08

Ministry of Defence Annual Report and Accounts 2007-2008 Volume I: Annual Performance Report Presented pursuant to the GRA Act 2000 c.20, s.6 Ministry of Defence Annual Report and Accounts Volume I including the Annual Performance Report and Consolidated Departmental Resource Accounts 2007-08 (For the year ended 31 March 2008) Laid in accordance with the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 21 July 2008 London: The Stationery Office 21 July 2008 HC 850-I £51.45 Not to be sold separately © Crown Copyright 2008 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and other departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. For any other use of this material please write to Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU or e-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978 0 10 295509 5 Introduction i. The Ministry of Defence’s Annual Report and Accounts is a comprehensive overview of Defence and how the Department has used the resources authorised by Parliament from April 2007 to March 2008. It has two main sections: the first comprises the Department’s Annual Performance Report for 2007-08, including performance against our Public Service Agreement (PSA) targets. -

MOD Records Appraisal Report 2020

Appraisal Report 22 December 2020 © Crown copyright 2020 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence or email [email protected]. Where we have identified any third-party copyright information, you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available for download at nationalarchives.gov.uk. Ministry of Defence and Armed Forces - Records Appraisal Report Appraisal Report Ministry of Defence and Armed Forces 1963 – 2020 CONTENTS Executive Summary 4 Background Information 6 Selection Decisions 18 Technical Report 23 Annex A - Generic records selection criteria 43 Index 45 22 December 2020 Page 2 of 45 Document History Draft No Date Appraisal Stage MOD enters key information. Preliminary ideas expressed for the sort of material it 0.1 18 Dec 13 wishes to select. Executive summary Complete completed in draft. Draft sent to TNA for consultation. Specific decisions for groups of records have been made and any ‘review’ has been 0.2 28 Jan 14 recorded. This must be done through Complete consultation between TNA and MOD’s DRO but may involve a wider discussion at TNA. Final draft. Submission of consultation draft 0.3 3 Feb 14 Complete to Records Decision Panel for agreement. 1.0 1 Aug 14 Published Complete MOD enters updated information. Draft sent 1.1 23 Jul 20 Complete to internal stakeholders. 1.2 24 Aug 20 Draft sent to internal stakeholders. -

Download The

TRANSFORMATION TRANSFORMED: THE ^ WAR ON TERROR' AND THE .MODERNISATION OF THE BRITISH MILITARY ' By SAMUEL LYON B.A., University of Oxford, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR- THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Political Science) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2006 © Samuel Lyon, 2006 • 11 ABSTRACT This thesis assesses the transformation of the British Military from the mid-1990s up until the current day. It addresses how the end of the Cold War brought a change in what was demanded of the British Armed Forces, and that since then, those Forces have adapted to that changed demand, altering their structure, tactics and equipment in order to deal with these new tasks and to exploit technological changes. Yet, as this thesis explores, transformation has not proceeded at a uniform pace, with the British experiencing several stages of transformative progress, and some of regress. Starting with the Strategic Defence Review of 1998, this thesis traces the overall picture of transformation in the United Kingdom, looking at how it is managed, why it occurred, and where it is going. In particular though, it focuses on the stops and starts in the transformative process, and connects these primarily to the consequences of the Blair Government's most important decision of all its time in power - being America's closest ally after the terror attacks of September 11th 2001. Following these commitments, Britain committed to an even greater transformation of its military, set out in the Strategic Defence Review: A New Chapter in 2002. -

Strategic Defence Review 1998: Politics, Power and Influence in Government Decisions1

Strategic Defence Review 1998: Politics, Power and Influence in Government Decisions1 Robert Grattan, Faculty of Business and Law, Bristol Business School, UWE, Bristol, UK Nicholas O’Regan, Faculty of Business and Law, Bristol Business School, UWE, Bristol, UK Glenn Parry (Corresponding author), Faculty of Business and Law, Bristol Business School, UWE, Bristol, UK Article Running Head: Strategic Defence Review 1998 Main Message: Politics, power and influence impact upon strategy as demonstrated in this work where the intention to produce a foreign policy based Strategic Defence Review was forgone during last minute adjustments and compromises over money. Key Points: The 1998 Strategic Defence Review was conducted using logical analysis of foreign policy to identify requirements, but final costs exceeded funding allowed by the Treasury so changes were made. The success of individuals in a strategic process is a function of the power they can wield directly and the support that they can muster. Strategic aspirations are always bounded by resource limitations so managers may have to make changes, however rigorous and logical their arguments. 1 J.E.L. classification codes: D21; D83; MOO; M21; Z18 Introduction This paper seeks to present an overview of the UK Strategic Defence Review [SDR] 1997/98 from a strategy process perspective and adopts a view of SDR as an attempt to form strategy through discourse. SDR was a fine-grained, logical analysis of foreign and defence policy and was a response mechanism similar to that used by large organisations and governmental bodies when determining future strategic direction. The actual policies relating to defence that emerged are not considered, as content has been separated from process. -

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 22

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 22 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Crown Copyright/MOD. The photographs on pages 9, 12 and 91 have been reproduced with permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Photographs credited to MAP have been reproduced by kind permission of Military Aircraft Photographs. Copies of these, and of many others, may be obtained via http://www.mar.co.uk Copyright 2000: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2000 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361-4231 Typeset by Creative Associates 115 Magdalen Road Oxford OX4 1RS Printed by Professional Book Supplies Ltd 8 Station Yard Steventon Nr Abingdon OX13 6RX 3 CONTENTS EDITORIAL NOTE 5 THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE RAFHS SEMINAR ON 6 THE EVOLUTION OF AIR TRANSPORT WITHIN THE RAF THE FAR EAST TRANSPORT WING IN THE EARLY 104 1950s THE MARCH RETREAT OF 1918 - THE LAST 107 BATTLE OF THE ROYAL FLYING CORPS DOWDING AND HIS MANPOWER. THE CASE OF 126 HURRICANE AND SPITFIRE PILOTS OF THE RAF AND ITS RESERVES IN 11 GROUP AIR OBSERVER TRAINING, 1939-40 132 BOOK REVIEWS 137 AVAILABILITY OF BACK-ISSUES OF RAFHS 142 PUBLICATIONS LETTERS