The Limited Capacity of Management to Rescue UK Defence Policy: a Review and a Word of Caution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Chief of Defence Materiel Makes Offer to DE&S

Feb 11 Issue 33 desthe magazine for defenceider equipment and support New Chief of Defence Materiel makes offer to DE&S Bernard Gray’s message to DE&S staff See inside Technology Ambush hits Extension All-round Cutting edge on display the water of support vision engineering NEWS 4 5 Osprey is the star again DE&S staff have welcomed news that a soldier in Afghanistan has twice survived insurgents’ bullets thanks to the life-saving Osprey body armour. 6 Rivet Joint progresses The first of three aircraft in the Airseeker project, the US RC-135 Rivet Joint, has arrived in Texas for conversion to an RAF aircraft. 8 A clearer front line vision A programme to deliver thousands of world-beating 2011 night vision systems to the front line has been completed in short time by a DE&S team. feb Picture: Andrew Linnett 10 Chinook passes first flight test Flight testing of the first Chinook Mk4 aircraft for the RAF has taken place, another step in a project to deliver an essentially new aircraft into service. 12 Bridging the gap Soldiers on operations can now cross obstacles thanks to a portable bridging system which has been procured by DE&S. 13 Focus on base security Extra surveillance has been provided to forward bases in Afghanistan with new tripod-mounted short-range cameras. cover image 14 ‘Troops want for nothing’ Soldiers in Afghanistan ‘want for nothing’ and Bernard Gray has addressed staff in town hall sessions at Abbey Wood after taking over as Chief of Defence Materiel last have ‘the very best’ equipment, according to the month. -

Towards a Tier One Royal Air Force

TOWARDS A TIER ONE ROYAL AIR FORCE MARK GUNZINGER JACOB COHN LUKAS AUTENRIED RYAN BOONE TOWARDS A TIER ONE ROYAL AIR FORCE MARK GUNZINGER JACOB COHN LUKAS AUTENRIED RYAN BOONE 2019 ABOUT THE CENTER FOR STRATEGIC AND BUDGETARY ASSESSMENTS (CSBA) The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments is an independent, nonpartisan policy research institute established to promote innovative thinking and debate about national security strategy and investment options. CSBA’s analysis focuses on key questions related to existing and emerging threats to U.S. national security, and its goal is to enable policymakers to make informed decisions on matters of strategy, security policy, and resource allocation. ©2019 Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. All rights reserved. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Mark Gunzinger is a Senior Fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. Mr. Gunzinger has served as the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Forces, Transformation and Resources. A retired Air Force Colonel and Command Pilot, he joined the Office of the Secretary of Defense in 2004 and was appointed to the Senior Executive Service and served as Principal Director of the Department’s central staff for the 2005–2006 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR). He served as Director for Defense Transformation, Force Planning and Resources on the National Security Council staff. Mr. Gunzinger holds an M.S. in National Security Strategy from the National War College, a Master of Airpower Art and Science degree from the School of Advanced Air and Space Studies, an M.P.A. from Central Michigan University, and a B.S. in Chemistry from the United States Air Force Academy. -

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 35

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 35 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First published in the UK in 2005 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Northmoor OX29 5UH 3 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-Marshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman Group Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary Group Captain K J Dearman Membership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol AMRAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA Members Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA *J S Cox Esq BA MA *Dr M A Fopp MA FMA FIMgt *Group Captain C J Finn MPhil RAF *Wing Commander W A D Carter RAF Wing Commander C Cummings Editor & Publications Wing Commander C G Jefford MBE BA Manager *Ex Officio 4 CONTENTS THE EARLY DAYS by Wg Cdr Larry O’Hara 8 SUPPLY COMES OF AGE by Wg Cdr Colin Cummings 19 SUPPLY: TWO WARTIME EXAMPLES by Air Cdre Henry 34 Probert EXPLOSIVES by Wg Cdr Mike Wooldridge 41 NUCLEAR WEAPONS AND No 94 MU, RAF BARNHAM by 54 Air Cdre Mike Allisstone -

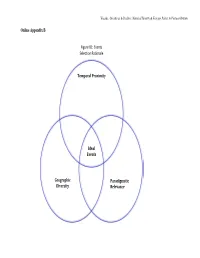

Online Appendix B Figure B1: Events Selection Rationale Temporal

Vucetic, Greatness & Decline: National Identity & Foreign Policy in Postwar Britain Online Appendix B Figure B1: Events Selection Rationale Temporal Proximity Ideal Events Geographic Paradigmatic Diversity Relevance Vucetic, Greatness & Decline: National Identity & Foreign Policy in Postwar Britain Online Appendix B—Postwar Defence Reviews in Chronological Order Sandys, D. (1957). Statement on defence, 1957 . London: Ministry of Defence. Retrieved on 8 April 2017 from http://filestore.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pdfs/small/cab-129-86-c-57-69-19.pdf Healey, D. (1966). Defence review: The statement on the defence estimates . London: Ministry of Defence. Retrieved on 8 April 2017 from http://filestore.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pdfs/small/cab-129-124-c-33.pdf Mason, R. (1975). Statement on the defence estimates London: Ministry of Defence. Retrieved on 8 April 2017 from http://filestore.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pdfs/small/cab-129-181-c-21.pdf Nott, J. (1981). The United Kingdom defence programme: The way forward. London: Ministry of Defence. Retrieved on 8 April 2017 from http://fc95d419f4478b3b6e5f-3f71d0fe2b653c4f00f32175760e96e7.r87.cf1.rackcdn.com/991284B4011C44C9AEB423DA04A7D54B.pdf King, T. (1990). Defence (Options for change). London: Ministry of Defence. Retrieved on 8 April 2017 from https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1990/jul/25/defence-options-for-change Rifkind, M. (1994). Front line first. London: Ministry of Defence. Retrieved on 8 April 2017 from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm199394/cmhansrd/1994-07-14/Debate-1.html Hoon, G. (2002). The strategic defence review: A new chapter. London: Ministry of Defence. Retrieved on 8 April 2017 from http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20090805012836/http://www.mod.uk/DefenceInternet/AboutDefence/CorporatePublications/ PolicyStrategyandPlanning/StrategicDefenceReviewANewChaptercm5566.htm Hoon, G. -

Ministry of Defence Departmental Overview 2019

A picture of the National Audit Office logo DEPARTMENTAL OVERVIEW 2019 MINISTRY OF DEFENCE OCTOBER 2019 If you are reading this document with a screen reader you may wish to use the bookmarks option to navigate through the parts. If you require any of the graphics in another format, we can provide this on request. Please email us at www.nao.org.uk/contact-us MINISTRY OF DEFENCE This overview summarises the work of the Ministry of Defence including what it does, how much it spends, recent and planned changes, and what to look out for across its main business areas and services. Bookmarks and Contents Overview CONTENTS THEMES IN DEFENCE About the Department How the Department is structured VALUE FOR MONEY Where the Department spends its money The Department’s assets and liabilities Major developments in 2018-19 OVERVIEW PART [01] Major developments and programmes page About the Department Affordability of the Department’s page Major developments3 and programmes– continued page15 – 22 PART [05] MoD approaches to procurement of projects and programmes Equipment Plan What to look out for Major equipment programmes– in Howthe 2018 the Equipment Department Plan is structured – Major equipment programmes in the 2018 Equipment Plan continued Exiting the European Union – Where the Department spends its money Managing public money Risks to managing public money The Department’s assets and liabilities – PART [02] Part [01] – Affordability of the Department’s Equipment Plan page16 – Major developments in 2018-19 – Accounting Officer scrutiny of challenges -

Andrew Dorman Michael D. Kandiah and Gillian Staerck ICBH Witness

edited by Andrew Dorman Michael D. Kandiah and Gillian Staerck ICBH Witness Seminar Programme The Nott Review The ICBH is grateful to the Ministry of Defence for help with the costs of producing and editing this seminar for publication The analysis, opinions and conclusions expressed or implied in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the JSCSC, the UK Ministry of Defence, any other Government agency or the ICBH. ICBH Witness Seminar Programme Programme Director: Dr Michael D. Kandiah © Institute of Contemporary British History, 2002 All rights reserved. This material is made available for use for personal research and study. We give per- mission for the entire files to be downloaded to your computer for such personal use only. For reproduction or further distribution of all or part of the file (except as constitutes fair dealing), permission must be sought from ICBH. Published by Institute of Contemporary British History Institute of Historical Research School of Advanced Study University of London Malet St London WC1E 7HU ISBN: 1 871348 72 2 The Nott Review (Cmnd 8288, The UK Defence Programme: The Way Forward) Held 20 June 2001, 2 p.m. – 6 p.m. Joint Services Command and Staff College Watchfield (near Swindon), Wiltshire Chaired by Geoffrey Till Paper by Andrew Dorman Seminar edited by Andrew Dorman, Michael D. Kandiah and Gillian Staerck Seminar organised by ICBH in conjunction with Defence Studies, King’s College London, and the Joint Service Command and Staff College, Ministry of -

EU Tank Breaks Cover

+(@ +(03@ VENDREDI 15 JUIN FRIDAY 15 JUNE Cerberus, véhicule 6x4 anti-émeutes page 3 EU tank New projectiles for Spanish Army will fire further breaks cover page 14 fter being kept under wraps, mobility and firing trials, the latter The first of these is the Athe French-German KNDS performed in Portugal, with 22 follow-on to the Leopard 2/ Group (Krauss-Maffei Wegmann rounds fired from the 120mm Leclerc MBT, which is called the + Nexter Defense Systems) has smoothbore gun. Main Ground Combat System and unveiled its first joint project, the The standard Leopard 2A7 has a potential in-service date EMBT, or European Main Battle has a three-person turret armed of around 2035. This could well Tank. Essentially a technology with a manually loaded 120mm be brought forward because the demonstrator, with further smoothbore gun, whereas the design of these two MBTs is now development, “the EMBT is a Leclerc turret is fitted with a many years old and the point will Radio logicielle tactique short-term response to the 120mm smoothbore gun fed by a be reached where they can no TRICS operational need of the market bustle-mounted automatic loader. longer be upgraded. page 5 for high-intensity battle tanks”. The Leclerc turret is lighter and The second programme is the The EMBT consists of the KMW more compact, which reduces the future artillery system. Called the Leopard 2A7 MBT platform fitted combined weight by six tonnes. Common Indirect Fire System, &0, '()(1&( with the Nexter Leclerc MBT According to KNDS, the this has a number of elements, turret. -

20091201-Je New Contracts Jan 2009-Final

In answer to PQ 303350 MOD Contracts entered into between 1 January 2009 and 31 October 2009 by Broad Value Range, Contractor Name, Start Date and Broad Industrial Heading. In answer to PQ Number 303350, dated 27 November 2009. Value Contractor Code Contract Start Date SIC Description Over £500m BAE SYSTEMS (OPERATIONS) LIMITED 01-Apr-09 Unknown Over £500m WESTLAND HELICOPTERS LIMITED 29-Sep-09 Gas £250m-£500m BAE SYSTEMS (OPERATIONS) LIMITED 01-Apr-09 Aircraft & Spacecraft £250m-£500m BAE SYSTEMS ELECTRONICS LIMITED 15-Jul-09 Weapons & Ammunition £250m-£500m BAE SYSTEMS SURFACE SHIPS SUPPORT LIMITED 10-Sep-09 Electricity £250m-£500m DEVONPORT ROYAL DOCKYARD LIMITED 05-Feb-09 Ship Building & Maintenance £100m-£250m BAE SYSTEMS SURFACE SHIPS LIMITED 21-Jul-09 Ship Building & Maintenance £100m-£250m DEVONPORT ROYAL DOCKYARD LIMITED 01-Apr-09 Ship Building & Maintenance £100m-£250m E D S DEFENCE LTD 13-May-09 Sewage and Refuse Disposal £100m-£250m EUROCOPTER UK LIMITED 18-Sep-09 Aircraft & Spacecraft £100m-£250m NAVISTAR DEFENSE LLC 20-Feb-09 Weapons & Ammunition £100m-£250m SKANSKA UK PLC 24-Apr-09 Construction £100m-£250m THALES OPTRONICS LTD 29-Jul-09 Instrument Engineering £100m-£250m VT AEROSPACE LIMITED 07-Jan-09 Education £100m-£250m WESTLAND HELICOPTERS LIMITED 01-Apr-09 Aircraft & Spacecraft £50m-£100m BP INTERNATIONAL LIMITED 01-Feb-09 Petroleum & Nuclear Fuel £50m-£100m EUROCOPTER 01-Jan-09 Aircraft & Spacecraft £50m-£100m INTEGRATED SURVIVABILITY TECHNOLOGIES LIMITED 01-Apr-09 Weapons & Ammunition £50m-£100m TURNER FACILITIES MANAGEMENT LTD 08-Jun-09 Legal Activities, Accounting, Business Management & Consultancy £25m-£50m AAH PHARMACEUTICALS LTD 09-Jan-09 Sale, Maintenance, & Repair of Motor Vehicles/Cycles £25m-£50m ANTEON LIMITED 12-Feb-09 Instrument Engineering £25m-£50m COMPASS CONTRACT SERVICES (U K)LIMITED 09-Jul-09 Hotels & Restaurants £25m-£50m DAF TRUCKS N.V. -

The Report of the Inquiry Into Unresolved Recognition for Past Acts of Naval and Military Gallantry and Valour

Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal THE REPORT OF THE INQUIRY INTO UNRESOLVED RECOGNITION FOR PAST ACTS OF NAVAL AND MILITARY GALLANTRY AND VALOUR THE REPORT OF THE INQUIRY INTO UNRESOLVED RECOGNITION FOR PAST ACTS OF NAVAL AND MILITARY GALLANTRY AND VALOUR This publication has been published by the Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal. Copies of this publication are available on the Tribunal’s website: www.defence-honours-tribunal.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2013 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal. Editing and design by Biotext, Canberra. LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL INQUIRY INTO UNRESOLVED RECOGNITION FOR PAST ACTS OF NAVAL AND MILITARY GALLANTRY AND VALOUR Senator The Hon. David Feeney Parliamentary Secretary for Defence Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Parliamentary Secretary, I am pleased to present the report of the Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal’s Inquiry into Unresolved Recognition for Past Acts of Naval and Military Gallantry and Valour. The Inquiry was conducted in accordance with the Terms of Reference. The Tribunal that conducted the Inquiry arrived unanimously at the findings and recommendations set out in this report. In accordance with the Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal Procedural Rules 2011, this report will be published on the Tribunal’s website — www.defence-honours-tribunal.gov.au — 20 working days after -

The Defence Industrial Ecosystem Delivering Security in an Uncertain World

Whitehall Report 2-11 The Defence Industrial Ecosystem Delivering Security in an Uncertain World Henrik Heidenkamp, John Louth and Trevor Taylor www.rusi.org The views expressed in this paper are the authors’ own, and do not necessarily reflect those of RUSI or any other institutions with which the authors are associated. Comments pertaining to this report are invited and should be forwarded to the series editor: Adrian Johnson, Director of Publications, Royal United Services Institute, Whitehall, London, SW1A 2ET, United Kingdom, or via email to publications@ rusi.org Published in 2011 by the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies. Reproduction without the express permission of RUSI is prohibited. About RUSI Publications Director of Publications: Adrian Johnson Publications Manager: Ashlee Godwin Editorial Assistant: Charles Dougherty Paper or electronic copies of this and other reports are available by contacting [email protected]. Printed in the UK by Stephen Austin and Sons, Ltd. Contents Defence in an Uncertain World 1 Defence Industries 6 The Defence Industrial Ecosystem 12 Conclusions: Exploring Complexity 19 Notes and References 20 About the Authors 23 Defence in an Uncertain World In October 2010, the government of the United Kingdom published its National Security Strategy and the Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR). Preparation was crammed between an election in May earlier that year, and the publication of a comprehensive spending review in the autumn – a period of time also defined by the negotiation, formation and initiation of the first UK peacetime coalition government in generations. Whilst it is fair to recall that both Whitehall and Westminster had been preparing for a defence review for at least eighteen months prior to the election, there is little doubt that the impression left by the SDSR in particular was of a process that was short-term in nature, rushed, and undertaken without full regard to all of the forces, factors and variables that coagulate to form defence and security capability. -

A Brief Guide to Previous British Defence Reviews

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07313, 19 November 2015 A brief guide to previous By Nigel Walker British defence reviews Claire Mills Inside: 1. Background 2. Post-World War Two 3. Sandys Review – 1957 4. Healey Reviews – 1965-1968 5. Mason Review – 1974-1975 6. Nott Review – 1981 7. Options for Change – 1990 8. The Defence Costs Study – 1994 9. Strategic Defence Review and the SDR New Chapter – 1998 and 2002 10. Defence White Paper – 2003- 2004 11. Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR) – 2010 12. Developments since the 2010 SDSR www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 07313, 19 November 2015 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Background 4 2. Post-World War Two 6 3. Sandys Review – 1957 7 4. Healey Reviews – 1965-1968 9 5. Mason Review – 1974-1975 10 6. Nott Review – 1981 12 7. Options for Change – 1990 14 8. The Defence Costs Study – 1994 17 9. Strategic Defence Review and the SDR New Chapter – 1998 and 2002 19 9.1 SDR New Chapter 21 10. Defence White Paper – 2003-2004 22 11. Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR) – 2010 27 11.1 National security tasks and planning guidelines 27 11.2 Alliances and partnerships 28 11.3 Defence and the armed forces 28 12. Developments since the 2010 SDSR 30 12.1 Personnel 30 12.2 Equipment 30 12.3 Defence spending 30 12.4 Operational deployments 31 12.5 Reserves 31 12.6 Defence reform 32 Cover page image copyright: MOD Sign by UK Ministry of Defence. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 / image cropped. -

Ministry of Defence Acronyms and Abbreviations

Acronym Long Title 1ACC No. 1 Air Control Centre 1SL First Sea Lord 200D Second OOD 200W Second 00W 2C Second Customer 2C (CL) Second Customer (Core Leadership) 2C (PM) Second Customer (Pivotal Management) 2CMG Customer 2 Management Group 2IC Second in Command 2Lt Second Lieutenant 2nd PUS Second Permanent Under Secretary of State 2SL Second Sea Lord 2SL/CNH Second Sea Lord Commander in Chief Naval Home Command 3GL Third Generation Language 3IC Third in Command 3PL Third Party Logistics 3PN Third Party Nationals 4C Co‐operation Co‐ordination Communication Control 4GL Fourth Generation Language A&A Alteration & Addition A&A Approval and Authorisation A&AEW Avionics And Air Electronic Warfare A&E Assurance and Evaluations A&ER Ammunition and Explosives Regulations A&F Assessment and Feedback A&RP Activity & Resource Planning A&SD Arms and Service Director A/AS Advanced/Advanced Supplementary A/D conv Analogue/ Digital Conversion A/G Air‐to‐Ground A/G/A Air Ground Air A/R As Required A/S Anti‐Submarine A/S or AS Anti Submarine A/WST Avionic/Weapons, Systems Trainer A3*G Acquisition 3‐Star Group A3I Accelerated Architecture Acquisition Initiative A3P Advanced Avionics Architectures and Packaging AA Acceptance Authority AA Active Adjunct AA Administering Authority AA Administrative Assistant AA Air Adviser AA Air Attache AA Air‐to‐Air AA Alternative Assumption AA Anti‐Aircraft AA Application Administrator AA Area Administrator AA Australian Army AAA Anti‐Aircraft Artillery AAA Automatic Anti‐Aircraft AAAD Airborne Anti‐Armour Defence Acronym