Erasmus and the Colloquial Emotions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in Criminal Trials in the Julio-Claudian Era

Women in Criminal Trials in the Julio-Claudian Era by Tracy Lynn Deline B.A., University of Saskatchewan, 1994 M.A., University of Saskatchewan, 2001 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Classics) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) September 2009 © Tracy Lynn Deline, 2009 Abstract This study focuses on the intersection of three general areas: elite Roman women, criminal law, and Julio-Claudian politics. Chapter one provides background material on the literary and legal source material used in this study and considers the cases of Augustus’ daughter and granddaughter as a backdrop to the legal and political thinking that follows. The remainder of the dissertation is divided according to women’s roles in criminal trials. Chapter two, encompassing the largest body of evidence, addresses the role of women as defendants, and this chapter is split into three thematic parts that concentrate on charges of adultery, treason, and other crimes. A recurring question is whether the defendants were indicted for reasons specific to them or the indictments were meant to injure their male family members politically. Analysis of these cases reveals that most of the accused women suffered harm without the damage being shared by their male family members. Chapter three considers that a handful of powerful women also filled the role of prosecutor, a role technically denied to them under the law. Resourceful and powerful imperial women like Messalina and Agrippina found ways to use criminal accusations to remove political enemies. Chapter four investigates women in the role of witnesses in criminal trials. -

AELIANUS TACTICUS, Translated from the Greek Into Latin By

AELIANUS TACTICUS, translated from the Greek into Latin by FRANCESCO ROBORTELLO and THEODORUS GAZA, Περὶ Στρατηγικῶν Τάξεων Ἑλληνικῶν [Latin translation: De militaribus ordinibus instituendis more græcorum and De instruendis aciebus], with a manuscript fragment of SIGEBERT OF GEMBLOUX [SIGEBERT GEMBLACENSIS], Chronica, and manuscript fragments from a Glossary and a Grammar In Latin (with some Greek), imprint on paper, with three manuscript fragments in Latin (with some Low German in one fragment) Venice, Andreas and Jacobus Spinellus, 1552 (imprint); Western Germany(?), c. 1140-60; Northwestern Germany(?), c. 1300-1350; Northwestern Germany(?), c. 1400-1450 In-4o format, preceded by one manuscript flyleaf (medieval fragment) and followed one paper flyleaf and two small manuscript flyleaves (both medieval fragments), printed [8 pp.], pp. 1-64, 73-77, [78], [24 pp.], incomplete (collation, sig. *4, A-G4, H4? [sig. H on outer sheet and sig. I ii on inner sheet, but with no disruption to pagination; a quire does appear to be lacking following this one, with loss of text], K3 [last leaf cancelled], A-C4), printed in Roman and Italic type, printer’s device on sig. K3 verso (U104 in EDIT16; see Online Resources), two engraved ornamental initials, numerous printed diagrams and tables, some of which incorporate woodcuts of soldiers alone or in formation, slight staining in the margins, some small losses to the outer edges of individual leaves, sig. K1 (pp. 73-74) is loose. Bound in sixteenth-century leather, blind-tooled with four concentric rectangular -

1989 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program School of Theatre and Dance Illinois State University

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Illinois Shakespeare Festival Fine Arts Summer 1989 1989 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program School of Theatre and Dance Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/isf Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation School of Theatre and Dance, "1989 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program" (1989). Illinois Shakespeare Festival. 8. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/isf/8 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Fine Arts at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Illinois Shakespeare Festival by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The 1989 Illinois Shakespeare I Illinois State University Illinois Shakespeare Festival Dear friends and patrons, Welcome to the twelfth annual Illinois Shakespeare Festival. In honor of his great contributions to the Festival, we dedicate this season to the memory of Douglas Harris, our friend, colleague and teacher. Douglas died in a plane crash in the fall of 1988 after having directed an immensely successful production of Richard III last summer. His contributions and inspiration will be missed by many of us, staff and audience alike. We look forward to the opportunity to share this season's wonderful plays, including our first non-Shakespeare play. For 1989 and 1990 we intend to experiment with performing classical Illinois State University plays in addition to Shakespeare that are suited to our acting company and to our theatre space. Office of the President We are excited about the experiment and will STATE OF ILLINOIS look forward to your responses. -

Epigraphical Research and Historical Scholarship, 1530-1603

Epigraphical Research and Historical Scholarship, 1530-1603 William Stenhouse University College London A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Ph.D degree, December 2001 ProQuest Number: 10014364 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10014364 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis explores the transmission of information about classical inscriptions and their use in historical scholarship between 1530 and 1603. It aims to demonstrate that antiquarians' approach to one form of material non-narrative evidence for the ancient world reveals a developed sense of history, and that this approach can be seen as part of a more general interest in expanding the subject matter of history and the range of sources with which it was examined. It examines the milieu of the men who studied inscriptions, arguing that the training and intellectual networks of these men, as well as the need to secure patronage and the constraints of printing, were determining factors in the scholarship they undertook. It then considers the first collections of inscriptions that aimed at a comprehensive survey, and the systems of classification within these collections, to show that these allowed scholars to produce lists and series of features in the ancient world; the conventions used to record inscriptions and what scholars meant by an accurate transcription; and how these conclusions can influence our attitude to men who reconstructed or forged classical material in this period. -

Xerox University Microfilms

SKEPTICISM AND DOCTRINE IN THE WORKS OF CYRANO DE BERGERAC (1619--1655) Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Johnson, Charles Richard, 1927- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 06:30:47 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288336 INFORMATION TC USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. -

Cyrano De Bergerac

Cyrano de Bergerac Summer Reading Guide - English 10 Howdy, sophomores! Cyrano de Bergerac is a delightful French play by Edmond Rostand about a swashbuckling hero with a very large nose. It is one of my favorites! Read this entire guide before starting the play. The beginning can be tough to get through because there are many confusing names and characters, but stick with it and you won’t be disappointed! On the first day of class, there will be a Reading Quiz to test your knowledge of this guide and your comprehension of the play’s main events and characters. If you are in the honors section, you will also write a Timed Writing essay the first week of school. After school starts, we will analyze the play in class through discussions and various writing assignments. We will conclude the unit by watching a French film adaptation and comparing it to the play. By the way, my class is a No Spoiler Zone. This means that you may NOT spoil significant plot events to classmates who have not yet read the book. If you have questions about the reading this summer, please email me at [email protected]. I’ll see you in the fall! - Mrs. Lee 1 Introduction Cyrano de Bergerac is a 5-act play by French dramatist and poet Edmond Rostand (1868-1918). Our class version was translated into English by Gertrude Hall. Since its 1897 Paris debut, the play has enjoyed numerous productions in multiple countries. Cultural & Historical Background By the end of the 1800s, industrialization was taking place in most of Europe, including France, and with it came a more scientific way of looking at things. -

Rina Mahoney

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Rina Mahoney Talent Representation Telephone Elizabeth Fieldhouse +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected] Address Hamilton Hodell, 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Theatre Title Role Director Theatre/Producer HAMLET Gertrude Damian Cruden Shakespeares Rose Theatre, York TWELFTH NIGHT Maria Joyce Branagh Shakespeares Rose Theatre, York DEATH OF A SALESMAN The Woman Sarah Frankcom Royal Exchange Theatre Shakespeare's Rose MACBETH Lady Macduff/Young Siward Damian Cruden Theatre/Lunchbox Productions Shakespeare's Rose A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM Peter Quince Juliet Forster Theatre/Lunchbox Productions THE PETAL AND THE ORCHID Kathryn Cat Robey Underexposed Theatre THE SECRET GARDEN Ayah/Dr Bres Liz Stevenson Theatre by the Lake ROMEO AND JULIET Nurse Justin Audibert RSC (BBC Live) MACBETH Witch 2 Justin Audibert RSC (BBC Live) ZILLA Rumani Joyce Branagh The Gap Project Duke of Venice/Portia's THE MERCHANT OF VENICE Polly Findlay RSC Servant OTHELLO Ensemble/Emillia Understudy Iqbal Khan RSC Birmingham Repertory FADES, BRAIDS AND KEEPING IT REAL Eva Antionette Lecester Theatre/Sharon Foster Productions CALCUTTA KOSHER Maki Janet Steel Arcola/Kali ARE WE NEARLY THERE YET? Various Matthew Lloyd Wilton's Music Hall FLINT STREET NATIVITY The Angel Matthew Lloyd Hull Truck Theatre MATCH Jasmin Jenny Stephens Hearth UNWRAPPED FESTIVAL Various Gwenda Hughes Birmingham Repertory Theatre HAPPY NOW Bea Matthew Lloyd Hull Truck Theatre Company MIRIAM ON 34TH STREET Kathy Jenny Stephens Something & Nothing -

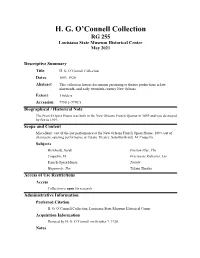

H. G. O'connell Collection

H. G. O’Connell Collection RG 255 Louisiana State Museum Historical Center May 2021 Descriptive Summary Title: H. G. O’Connell Collection Dates: 1893–1920 Abstract: This collection houses documents pertaining to theater productions in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century New Orleans. Extent: 5 folders Accession: 7790.1–7790.5 Biographical / Historical Note The French Opera House was built in the New Orleans French Quarter in 1859 and was destroyed by fire in 1919. Scope and Content Miscellany: cast of the last performance at the New Orleans French Opera House; 1893 cast of characters; opening performance at Tulane Theatre; Sara Bernhardt, M. Coquelin. Subjects Bernhardt, Sarah Passion Play, The Coquelin, M. Precieuses Ridicules, Les French Opera House Tartufe Huguenots, The Tulane Theatre Access of Use Restrictions Access Collection is open for research. Administrative Information Preferred Citation H. G. O’Connell Collection, Louisiana State Museum Historical Center Acquisition Information Donated by H. G. O’Connell on October 7, 1920. Notes Documents are in poor condition, and some portions are in French. List of Content Folder Date Item Description Newspaper clipping from November 30, 1893. Cast list of production of Tartufe at the French Opera House. Headlining actor: Folder 1 1893 November 30 M. Coquelin. Theater program from week of March 4, 1901 at Tulane Theatre. Includes cast list of productions of La Tosca, Cyrano de Bergerac, Phedre, Les Precieuses Ridicules, and La Dame Aux Camelias. Folder 2 1901 March 4 Headlining actors: Sarah Bernhardt and M.Coquelin. Theater program from a production of The Passion Play on Sunday April 16, 1916 at the French Opera House. -

{PDF EPUB} Doctor Who the Mind Robber by Peter Ling Doctor Who: the Mind Robber by Peter Ling

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Doctor Who The Mind Robber by Peter Ling Doctor Who: The Mind Robber by Peter Ling. After an emergency dematerialisation, the TARDIS lands in a weird white void. Jamie and Zoe are tempted out of the time machine into a trap, while the Doctor fends off a psychic assault. In a desperate bid to escape, the Doctor tries to pilot the TARDIS somewhere else, only for the time machine to break apart. Suddenly, the three companions find themselves in a surreal world where imagination has become reality, populated by characters out of folklore and literature. They must navigate a series of riddles and deadly encounters to reach the mysterious Master of the realm. But what designs does he have for the Doctor? Production. Just before joining Doctor Who , story editor Derrick Sherwin and his assistant, Terrance Dicks, had written for the soap opera Crossroads , co- created by Peter Ling. The three men regularly travelled together by train and, one day in late 1967, Ling remarked on the way that soap opera characters could be treated like real people by some fans. Sherwin suggested that this might form a suitable basis for a Doctor Who story and, shortly thereafter, Ling put together a proposal called “The Fact Of Fiction”. On the basis of this submission, on December 20th, Ling was commissioned to write an outline for a six-part story, now entitled “Man Power”. Early in the new year, the serial's length was truncated to four episodes; the title also underwent a slight change to “Manpower”, although this would be applied inconsistently. -

A Lesson for Cicero De Oratore 3,12.45: Laelia

Anne Leen, Professor of Classics Furman University September 2008 Lesson Plan for Cicero, De Oratore 3.12.45 Laelia's Latin Pronunciation I. Introduction Cicero's De Oratore is a treatise on rhetoric in dialogue form written in 55 BCE. The principal speakers are the orators Lucius Licinius Crassus (140-91 BCE) and Marcus Antonius (143-87 BCE), the grandfather of the Triumvir. The dramatic date of the dialogue is September 91 BCE. The setting is the Tusculan villa of Antonius. While the work as a whole addresses the ideal orator, Book 3 is devoted largely to good style, the first requirement of which is pure and correct Latin. The topic at hand in this passage is pronunciation, defined as a matter of regulating the tongue, breath, and tone of voice (lingua et spiritus et vocis sonus, 3.11.40). The speaker, Crassus, has noticed the recent affectation of rustic pronunciation in people who desire to evoke the sounds of what they wrongly think of as the purer diction of the past, and correspondingly the values of antiquity. To Crassus this is misguided and ill-informed. The urban Roman sound that must be emulated lacks rustification and instead mirrors ancient Roman diction, the only remaining traces of which he finds in the speech of his mother-in-law, Laelia, as he explains. II. Marcus Tullius Cicero, De Oratore 3.12.45 Equidem cum audio socrum meam Laeliam - facilius enim mulieres incorruptam antiquitatem conservant, quod multorum sermonis expertes ea tenent semper, quae prima didicerunt - sed eam sic audio, ut Plautum mihi aut Naevium videar audire, sono ipso vocis ita recto et simplici est, ut nihil ostentationis aut imitationis adferre videatur; ex quo sic locutum esse eius patrem iudico, sic maiores; non aspere ut ille, quem dixi, non vaste, non rustice, non hiulce, sed presse et aequabiliter et leniter. -

*** Le Explicationes Rappresentano Il Primo Significativo Com- Mento Cinquecentesco Alla Poetica Di Aristotele Dopo La Tradu- Zi

Anno II ISSN 2421-4191 2016 DOI : 10.6092/2421-4191/2016.2.153-174 FRANCESCO ROBORTELLO IN LIBRUM ARISTOTELIS DE ARTE POETICA EXPLICATIONES Francesco Robortello (Udine 1516 - Padova 1567), allievo di Gregorio Amaseo a Padova e di Romolo Amaseo a Bologna, iniziò l’attività accademica nel 1538, a Lucca, come docente di eloquenza. Chiamato a decla- mare l’orazione inaugurale per la ripresa delle attività dello Studio pisano (1° novembre 1543), divenne nella stessa sede lettore di humanae litterae , tenendo corsi, tra l’altro, sulle opere retoriche e morali di Cicerone. Nel 1548 – anno della pubblicazione di alcune delle sue opere più significative – Robortello si trasferì a Venezia, succedendo a Giambattista Egnazio nell’insegnamento di lettere greche e latine. Proprio durante il soggiorno veneziano intensi- ficò la sua attività filologica, di cui l’edizione delle sette tragedie di Eschi- lo è uno dei risultati di maggiore rilievo. Nel 1552 a Padova ricoprì la cattedra di eloquenza greca e latina, prendendo il posto di Lazzaro Buo- namici. Risale al 1553 la nota polemica con Carlo Sigonio. Dopo un anno di insegnamento presso lo Studio di Bologna, il filologo udinese ritornò a Padova, dove morì nel 1567. MURATORI 1732; LIRUTI 1762, t. II, pp. 413-83; POMPELLA , in ROBORTELLO 1975, pp. 9-10; McCUAIG 1989, ad indicem ; BARSANTI 2000, p. 531; DONADI 2001, pp. 80-81; ZLOBEC DEL VECCHIO 2006- 2007 (per Robortello poeta); SCALON - GRIGGIO - ROZZO 2009. *** Le Explicationes rappresentano il primo significativo com- mento cinquecentesco alla Poetica di Aristotele dopo la tradu- zione latina di Alessandro Pazzi de’ Medici (ARISTOTELE 1536). -

M. Tullii Ciceronis Laelius De Amicitia

This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world’s books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that’s often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book’s long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google’s system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us.