Journal of San Diego History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

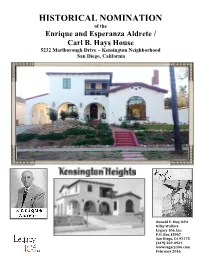

HISTORICAL NOMINATION of the Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B

HISTORICAL NOMINATION of the Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B. Hays House 5232 Marlborough Drive ~ Kensington Neighborhood San Diego, California Ronald V. May, RPA Kiley Wallace Legacy 106, Inc. P.O. Box 15967 San Diego, CA 92175 (619) 269-3924 www.legacy106.com February 2016 1 HISTORIC HOUSE RESEARCH Ronald V. May, RPA, President and Principal Investigator Kiley Wallace, Vice President and Architectural Historian P.O. Box 15967 • San Diego, CA 92175 Phone (619) 269-3924 • http://www.legacy106.com 2 3 State of California – The Resources Agency Primary # ___________________________________ DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # ______________________________________ PRIMARY RECORD Trinomial __________________________________ NRHP Status Code 3S Other Listings ___________________________________________________________ Review Code _____ Reviewer ____________________________ Date __________ Page 3 of 38 *Resource Name or #: The Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B. Hays House P1. Other Identifier: 5232 Marlborough Drive, San Diego, CA 92116 *P2. Location: Not for Publication Unrestricted *a. County: San Diego and (P2b and P2c or P2d. Attach a Location Map as necessary.) *b. USGS 7.5' Quad: La Mesa Date: 1997 Maptech, Inc.T ; R ; ¼ of ¼ of Sec ; M.D. B.M. c. Address: 5232 Marlborough Dr. City: San Diego Zip: 92116 d. UTM: Zone: 11 ; mE/ mN (G.P.S.) e. Other Locational Data: (e.g., parcel #, directions to resource, elevation, etc.) Elevation: 380 feet Legal Description: Lots Three Hundred Twenty-three and Three Hundred Twenty-four of KENSINGTON HEIGHTS UNIT NO. 3, according to Map thereof No. 1948, filed in the Office of the County Recorder, San Diego County, September 28, 1926. It is APN # 440-044-08-00 and 440-044-09-00. -

Arciiltecture

· BALBOA PARK· CENTRAL MESA PRECISE PLAN Precise Plan • Architecture ARCIIlTECTURE The goal of this section is to rehabilitate and modify the architecture of the Central Mesa ina manner which preserves its historic and aesthetic significance while providing for functional needs. The existing structures built for the 1915 and the 1935 Expositions are both historically and architecturally significant and should be reconstructed or rehabilitated. Not only should the individual structures be preserved, but the entire ensemble in its original composition should be preserved and restored wherever possible. It is the historic relationship between the built and the outdoor environment that is the hallmark of the two Expositions. Because each structure affects its site context to such a great degree, it is vital to the preservation of the historic district that every effort be made to preserve and restore original Exposition building footprints and elevations wherever possible. For this reason, emphasis has been placed on minimizing architectural additions unless they are reconstructions of significant historical features. Five major types of architectural modifications are recommended for the Central Mesa and are briefly described below. 1. Preservation and maintenance of existing structures. In the case of historically significant architecture, this involves preserving the historical significance of the structure and restoring lost historical features wherever possible. Buildings which are not historically significant should be preserved and maintained in good condition. 2. Reconstructions . This type of modification involves the reconstruction of historic buildings that have deteriorated to a point that prevents rehabilitation of the existing structure. This type of modification also includes the reconstruction of historically significant architectural features that have been lost. -

George White Marston Document Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8bk1j48 Online items available George White Marston Document Collection Finding aid created by San Diego City Clerk's Archives staff using RecordEXPRESS San Diego City Clerk's Archives 202 C Street San Diego, California 92101 (619) 235-5247 [email protected] http://www.sandiego.gov/city-clerk/inforecords/archive.shtml 2019 George White Marston Document George W. Marston Documents 1 Collection Descriptive Summary Title: George White Marston Document Collection Dates: 1874 to 1950 Collection Number: George W. Marston Documents Creator/Collector: George W. MarstonAnna Lee Gunn MarstonGrant ConardAllen H. WrightA. M. WadstromW. C. CrandallLester T. OlmsteadA. S. HillF. M. LockwoodHarry C. ClarkJ. Edward KeatingPhilip MorseDr. D. GochenauerJohn SmithEd FletcherPatrick MartinMelville KlauberM. L. WardRobert W. FlackA. P. MillsClark M. FooteA. E. HortonA. OverbaughWilliam H. CarlsonH. T. ChristianE. F. RockfellowErnest E. WhiteA. MoranA. F. CrowellH. R. AndrewsGrant ConardGeorge P. MarstonRachel WegeforthW. P. B. PrenticeF. R. BurnhamKate O. SessionsMarstonGunnWardKlauberMartinFletcherSmithGochenauerMorseKeatingClarkLockwoodHillOlmsteadCrandalWadstromFlackMillsKeatingFooteLockwoodWrightChristianCarlsonConardSpaldingScrippsKellyGrantBallouLuceAngierWildeBartholomewSessionsBaconRhodesOlmsteadSerranoClarkHillHallSessionsFerryWardDoyleCity of San DiegoCity Clerk, CIty of San DiegoBoard of Park CommissionersPark DepartmentMarston Campaign CommitteeThe Marston CompanyMarston Co. StoreMarston for MayorPark -

Inspired by Mexico: Architect Bertram Goodhue Introduces Spanish Colonial Revival Into Balboa Park

Inspired by Mexico: Architect Bertram Goodhue Introduces Spanish Colonial Revival into Balboa Park By Iris H.W. Engstrand G. Aubrey Davidson’s laudatory address to an excited crowd attending the opening of the Panama-California Exposition on January 1, 1915, gave no inkling that the Spanish Colonial architectural legacy that is so familiar to San Diegans today was ever in doubt. The buildings of this exposition have not been thrown up with the careless unconcern that characterizes a transient pleasure resort. They are part of the surroundings, with the aspect of permanence and far-seeing design...Here is pictured this happy combination of splendid temples, the story of the friars, the thrilling tale of the pioneers, the orderly conquest of commerce, coupled with the hopes of an El Dorado where life 1 can expand in this fragrant land of opportunity. G Aubrey Davidson, ca. 1915. ©SDHC #UT: 9112.1. As early as 1909, Davidson, then president of the Chamber of Commerce, had suggested that San Diego hold an exposition in 1915 to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal. When City Park was selected as the site in 1910, it seemed appropriate to rename the park for Spanish explorer Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, who had discovered the Pacific Ocean and claimed the Iris H. W. Engstrand, professor of history at the University of San Diego, is the author of books and articles on local history including San Diego: California’s Cornerstone; Reflections: A History of the San Diego Gas and Electric Company 1881-1991; Harley Knox; San Diego’s Mayor for the People and “The Origins of Balboa Park: A Prelude to the 1915 Exposition,” Journal of San Diego History, Summer 2010. -

The Making of the Panama-California Exposition, 1909-1915 by Richard W

The Journal of San Diego History SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY QUARTERLY Winter 1990, Volume 36, Number 1 Thomas L. Scharf, Editor The Making of the Panama-California Exposition, 1909-1915 by Richard W. Amero Researcher and Writer on the history of Balboa Park Images from this article On July 9, 1901, G. Aubrey Davidson, founder of the Southern Trust and Commerce Bank and Commerce Bank and president of the San Diego Chamber of Commerce, said San Diego should stage an exposition in 1915 to celebrate the completion of the Panama Canal. He told his fellow Chamber of Commerce members that San Diego would be the first American port of call north of the Panama Canal on the Pacific Coast. An exposition would call attention to the city and bolster an economy still shaky from the Wall Street panic of 1907. The Chamber of Commerce authorized Davidson to appoint a committee to look into his idea.1 Because the idea began with him, Davidson is called "the father of the exposition."2 On September 3, 1909, a special Chamber of Commerce committee formed the Panama- California Exposition Company and sent articles of incorporation to the Secretary of State in Sacramento.3 In 1910 San Diego had a population of 39,578, San Diego County 61,665, Los Angeles 319,198 and San Francisco 416,912. San Diego's meager population, the smallest of any city ever to attempt holding an international exposition, testifies to the city's extraordinary pluck and vitality.4 The Board of Directors of the Panama-California Exposition Company, on September 10, 1909, elected Ulysses S. -

Biographies of Established Masters

Biographies of Established Masters Historical Resources Board Jennifer Feeley Tricia Olsen, MCP Ricki Siegel Ginger Weatherford, MPS Historical Resources Board Staff 2011 i Master Architects Frank Allen Lincoln Rodgers George Adrian Applegarth Lloyd Ruocco Franklin Burnham Charles Salyers Comstock and Trotshe Rudolph Schindler C. E. Decker Thomas Shepherd Homer Delawie Edward Sibbert Edward Depew John Siebert Roy Drew George S. Spohr Russell Forester * John B. Stannard Ralph L. Frank Frank Stevenson George Gans Edgar V. Ullrich Irving Gill * Emmor Brooke Weaver Louis Gill William Wheeler Samuel Hamill Carleton Winslow William Sterling Hebbard John Lloyd Wright Henry H. Hester Eugene Hoffman Frank Hope, Sr. Frank L. Hope Jr. Clyde Hufbauer Herbert Jackson William Templeton Johnson Walter Keller Henry J. Lange Ilton E. Loveless Herbert Mann Norman Marsh Clifford May Wayne McAllister Kenneth McDonald, Jr. Frank Mead Robert Mosher Dale Naegle Richard Joseph Neutra O’Brien Brothers Herbert E. Palmer John & Donald B. Parkinson Wilbur D. Peugh Henry Harms Preibisius Quayle Brothers (Charles & Edward Quayle) Richard S. Requa Lilian Jenette Rice Sim Bruce Richards i Master Builders Juan Bandini Philip Barber Brawner and Hunter Carter Construction Company William Heath Davis The Dennstedt Building Company (Albert Lorenzo & Aaron Edward Dennstedt) David O. Dryden Jose Antonio Estudillo Allen H. Hilton Morris Irvin Fred Jarboe Arthur E. Keyes Juan Manuel Machado Archibald McCorkle Martin V. Melhorn Includes: Alberta Security Company & Bay City Construction Company William B. Melhorn Includes: Melhorn Construction Company Orville U. Miracle Lester Olmstead Pacific Building Company Pear Pearson of Pearson Construction Company Miguel de Pedroena, Jr. William Reed Nathan Rigdon R.P. -

Parker H. Jackson Personal Papers SDASM.SC.10078

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8cz39h5 Online items available The Descriptive Finding Guide for the Parker H. Jackson Personal Papers SDASM.SC.10078 Alan Renga San Diego Air and Space Museum Library and Archives 10/23/2014 2001 Pan American Plaza, Balboa Park San Diego 92101 URL: http://www.sandiegoairandspace.org/ The Descriptive Finding Guide for SDASM.SC.10078 1 the Parker H. Jackson Personal Papers SDASM.SC.10078 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: San Diego Air and Space Museum Library and Archives Title: Parker H. Jackson Personal Papers source: Jackson, Parker H. Identifier/Call Number: SDASM.SC.10078 Physical Description: 0.36 Cubic FeetOne Box Date (inclusive): 1913-2014 Abstract: Parker H. Jackson was the biographer Richard S. Requa, the master architect of the California Pacific International Exposition in 1935. This Collection includes documents from Jackson's studies of Requa. Conditions Governing Access The collection is open to researchers by appointment. Conditions Governing Use Some copyright may be reserved. Consult with the library director for more information. Preferred Citation [Item], [Filing Unit], [Series Title], [Subgroups], [Record Group Title and Number], [Repository “San Diego Air & Space Museum Library & Archives”] Immediate Source of Acquisition The materials in this collection were donated to the San Diego Air & Space Museum. The collection has been processed and is open for research. Biographical / Historical Parker H. Jackson was the biographer Richard S. Requa, the master architect of the California Pacific International Exposition in 1935. Jackson became fascinated with Requa and his influence on architectural design after purchasing a home designed by Requa located in the community of Kensington, in San Diego. -

Alcazar Garden Sign

Alcázar Garden - Balboa Park Richard Smith Requa 1881 - 1941 Seventy years later, the Moorish tiles were beginning to show their age. Tiles were cracked, chipped, and had chunks missing. In 2008, the garden was reconstructed to replicate the 1935 design by San Diego architect Richard Requa. During the restoration they found that moisture had seeped through, as tiles are porous and grout isn't perfect. With $50,000 in donations, the Committee of One Hundred, a nonprofit group dedicated to the park's Spanish Colonial architecture, replaced the damaged tiles and renovated the water fountains to their original grace and glory. The group commissioned 1,800 tiles that replicate the originals. Richard Smith Requa was an American architect, largely During the 1915 Panama-California Exhibition, this garden was T h e y e x p e c t t h i s known for his work in San Diego, California. Requa was the originally named Los Jardines de Montezuma (Montezuma Garden). renovation will last 20 Master Architect for the California Pacific International Exposition held in Balboa Park in 1935-36. He improved and In 1935, architect Richard Requa modified the garden by adding two years or so, but bought extended many of the already existing buildings from the delightful water fountains and eight tile benches. The garden was extra tiles for future patch 1915 Panama-California Exposition, as well as created new facilities including the Old Globe Theater. renamed Alcázar because its design is patterned after the courtyard work. His own designs were predominantly in the Spanish gardens of Alcázar Palace in Seville, Spain. -

Balboa Park, 1909-1911 the Rise and Fall of the Olmsted Plan

The Journal of San Diego History SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY QUARTERLY Winter 1982, Volume 28, Number 1 Edited by Thomas L. Scharf Balboa Park, 1909-1911 The Rise and Fall of the Olmsted Plan By Gregory Montes Copley Award, San Diego History Center 1981 Institute of History Images from this article BETWEEN 1868, the founding year of San Diego's City Park, now Balboa Park, and 1909, public open space protagonists and antagonists fought frequently over how to use the 1,400 acre tract. But as of 1909 it still was not clear which force would prevail in the long run. Due to San Diego's small population (39,000) and economy, caused mainly by its remote location in the southwesternmost United States, City Park represented somewhat of a draw by 1909. On the one hand, the relatively few, albeit vigorous, well-placed park supporters had managed to achieve since 1868 only about 100 acres of spotty, although pleasing landscaping, mainly in the southwest, northwest and southeast corners of City Park and construction of several long, winding boulevards throughout the tract.1 On the other hand, the park poachers had succeeded in permanently gaining only five acres for a non-park use, San Diego (or Russ) High School at the south side of City Park. Until 1909, public park protectors and town developers had not reached a consensus on how to proceed with City Park. Then came forward an idea which seemed to have something for both sides, more or less. The transformation of that proposal to reality brought divergent San Diegans together on some points and asunder on others. -

Written Historical and Descriptive Data Hals Ca-131

THE GEORGE WHITE AND ANNA GUNN MARSTON HOUSE, HALS CA-131 GARDENS HALS CA-131 3525 Seventh Avenue San Diego San Diego County California WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN LANDSCAPES SURVEY National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN LANDSCAPES SURVEY THE GEORGE WHITE AND ANNA GUNN MARSTON HOUSE, GARDENS (The Marston Garden) HALS NO. CA-131 Location: 3525 Seventh Avenue, San Diego, San Diego County, California Bounded by Seventh Avenue and Upas Street, adjoining the northwest boundary of Balboa Park in the City of San Diego, California 32.741689, -117.157756 (Center of main house, Google Earth, WGS84) Significance: The George Marston Gardens represent the lasting legacy of one of San Diego’s most important civic patrons, George Marston. The intact home and grounds reflect the genteel taste of the Marston Family as a whole who in the early 20th century elevated landscape settings, by example, toward city beautification in the dusty, semi-arid, coastal desert of San Diego. The Period of Significance encompasses the full occupancy of the Marston Family from 1905-1987, which reflects the completion of the house construction in 1905 to the death of daughter Mary Marston in 1987. George White Marston (1850-1946) and daughter Mary Marston (1879-1987) are the two notable family members most associated with the design and implementation of the Marston House Gardens, et al. The George W. Marston House (George White and Anna Gunn Marston House) was historically designated by the City of San Diego on 4 December 1970, Historic Site #40. -

C100 Brochure

THE COMMITTEE 1915-1916 OF ONE HUNDRED he Panama-California Exposition, held in Balboa Park during 1915-1916, introduced Working to preserve Balboa Park’s historic TSpanish Colonial Revival architecture to architecture,10 gardens, and public 0 spaces since 1967 Southern California and to millions of visitors. The El Prado grouping, connected by arcades, was dubbed a “Dream City” by the press. The California Building, its tower and quadrangle, the Spreckels Organ Pavilion, the Botanical Building, the plazas, SAFE ZONE: gardens and the many “temporary” buildings along All critical elements (text, images, graphic elements, El Prado have thrilled San Diegans for one hundred logos etc.) must be kept inside the blue box. All text should have an 0.0625 inch spacing from the fold lines. years. Exposition buildings had begun to deteriorate as early as 1922, when George Marston appealed to TRIMMING ZONE: the public for funds in his letter to the editor of the Please allow 0.125 inches cutting tolerance around San Diego Union: your card. We recommend no borders due to shifting in the cutting process, borders may appear uneven. BLEED ZONE 0.125 inches: WhyCOVER should the park buildings be saved? Make sure to extend the background images or colors Were they not built as temporary structures, all the way to the edge of the black outline. without any thought of being retained after FOLD LINES: the Exposition period? … the community “OUTSIDEhas grown slowly into conviction that what we have there in Balboa Park—which is IMPORTANT something more than mere buildings— Please send artwork without blue, purple, black and gray frames. -

San Diego History Center Is a Museum, Education Center, and Research Library Founded As the San Diego Historical Society in 1928

The Journal of San Diego Volume 61 Winter 2015 Numbers 1 • The Journal of San Diego History Diego San of Journal 1 • The Numbers 2015 Winter 61 Volume History Publication of The Journal of San Diego History is underwritten by a major grant from the Quest for Truth Foundation, established by the late James G. Scripps. Additional support is provided by “The Journal of San Diego History Fund” of the San Diego Foundation and private donors. The San Diego History Center is a museum, education center, and research library founded as the San Diego Historical Society in 1928. Its activities are supported by: the City of San Diego’s Commission for Arts and Culture; the County of San Diego; individuals; foundations; corporations; fund raising events; membership dues; admissions; shop sales; and rights and reproduction fees. Articles appearing in The Journal of San Diego History are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. The paper in the publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Science-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Front Cover: Clockwise: Casa de Balboa—headquarters of the San Diego History Center in Balboa Park. Photo by Richard Benton. Back Cover: San Diego & Its Vicinity, 1915 inside advertisement. Courtesy of SDHC Research Archives. Design and Layout: Allen Wynar Printing: Crest Offset Printing Editorial Assistants: Travis Degheri Cynthia van Stralen Joey Seymour The Journal of San Diego History IRIS H. W. ENGSTRAND MOLLY McCLAIN Editors THEODORE STRATHMAN DAVID MILLER Review Editors Published since 1955 by the SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY 1649 El Prado, Balboa Park, San Diego, California 92101 ISSN 0022-4383 The Journal of San Diego History VOLUME 61 WINTER 2015 NUMBER 1 Editorial Consultants Published quarterly by the San Diego History Center at 1649 El Prado, Balboa MATTHEW BOKOVOY Park, San Diego, California 92101.