San Diego Invites the World to Balboa Park a Second Time by Richard W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Diego's Class 1 Streetcars

San Diego’s Class 1 Streetcars Historic Landmark #339 Our History, Our Heritage, and Our Future 1910 - 1912: The Panama-California Exposition and the Creation of the Class 1 Streetcars In 1910 the long awaited opening of the Panama Canal was fast approaching. San Diego's leaders decided to use this event to advertise San Diego as the port of choice for ships traveling through the canal by holding the Panama-California Exposition. It was set to take place in 1915 and would be held on a parcel of land just north of downtown, soon to be named Balboa Park. Early San Diego developer and streetcar system owner, John D. Spreckels, directed his engineers at the San Diego Electric Railway Company to design a special new "state of the art" streetcar to carry patrons to and from the exposition at Balboa Park. The mastercar builders at the San Diego Electric Railway Co. designed a unique new streetcar just for San Diego's mild climate. These large and beautiful Arts & Crafts style streetcars became known as San Diego’s Class 1 streetcars. Spreckels approved the designs and an order for 24 of these brand new streetcars was sent to the renowned St. Louis Car Company for construction. 1912 - 1939: Class 1 Streetcars in operation throughout San Diego The Class 1 streetcars provided fun and dependable transportation to countless thousands of patrons from 1912 to 1939. They operated throughout all of San Diego's historic districts and neighborhoods, as well as to many outlying areas. The Class 1 streetcars successfully supplied the transportation needs for the large crowds that attended the 1915 Panama-California Exposition, and went on to serve through WWI, the Roaring Twenties, and the Great Depression. -

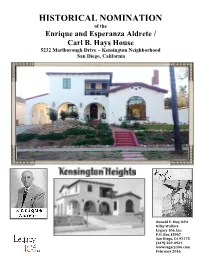

HISTORICAL NOMINATION of the Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B

HISTORICAL NOMINATION of the Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B. Hays House 5232 Marlborough Drive ~ Kensington Neighborhood San Diego, California Ronald V. May, RPA Kiley Wallace Legacy 106, Inc. P.O. Box 15967 San Diego, CA 92175 (619) 269-3924 www.legacy106.com February 2016 1 HISTORIC HOUSE RESEARCH Ronald V. May, RPA, President and Principal Investigator Kiley Wallace, Vice President and Architectural Historian P.O. Box 15967 • San Diego, CA 92175 Phone (619) 269-3924 • http://www.legacy106.com 2 3 State of California – The Resources Agency Primary # ___________________________________ DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # ______________________________________ PRIMARY RECORD Trinomial __________________________________ NRHP Status Code 3S Other Listings ___________________________________________________________ Review Code _____ Reviewer ____________________________ Date __________ Page 3 of 38 *Resource Name or #: The Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B. Hays House P1. Other Identifier: 5232 Marlborough Drive, San Diego, CA 92116 *P2. Location: Not for Publication Unrestricted *a. County: San Diego and (P2b and P2c or P2d. Attach a Location Map as necessary.) *b. USGS 7.5' Quad: La Mesa Date: 1997 Maptech, Inc.T ; R ; ¼ of ¼ of Sec ; M.D. B.M. c. Address: 5232 Marlborough Dr. City: San Diego Zip: 92116 d. UTM: Zone: 11 ; mE/ mN (G.P.S.) e. Other Locational Data: (e.g., parcel #, directions to resource, elevation, etc.) Elevation: 380 feet Legal Description: Lots Three Hundred Twenty-three and Three Hundred Twenty-four of KENSINGTON HEIGHTS UNIT NO. 3, according to Map thereof No. 1948, filed in the Office of the County Recorder, San Diego County, September 28, 1926. It is APN # 440-044-08-00 and 440-044-09-00. -

Cassius Carter Centre Stage Darlene Gould Davies

Cassius Carter Centre Stage Darlene Gould Davies Cassius Carter Centre Stage, that old and trusted friend, is gone. The theatre in the round at The Old Globe complex in Balboa Park had its days, and they were glorious. Who can forget “Charlie’s Aunt” (1970 and 1977), or the hilarious 1986 pro- duction of “Beyond the Fringe”? Was there ever a show in the Carter that enchanted audiences more than “Spoon River Anthology” (1969)? A. R. Gurney’s “The Din- ing Room” (1983) was delightful. Craig Noel’s staging of Alan Ayckbourn’s ultra- comedic trilogy “The Norman Conquests” (1979) still brings chuckles to those who remember. San Diegans will remember the Carter. It was a life well lived. Cassius Carter Centre Stage, built in 1968 and opened in early 1969, was di- rectly linked to the original Old Globe Theatre of the 1935-36 California-Pacific International Exposition in Balboa Park. It was not a new building but a renovation of Falstaff Tavern that sat next to The Old Globe.1 In fact, until Armistead Carter Falstaff Tavern ©SDHS, UT #82:13052, Union-Tribune Collection. Darlene Gould Davies has served on several San Diego City boards and commissions under five San Diego mayors, is Professor Emerita of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences at San Diego State University, and co-produced videos for the Mingei International Museum. She is currently a member of the Board of Directors of the San Diego Natural History Museum and has served as chair of the Balboa Park Committee. 119 The Journal of San Diego History Falstaff Tavern refreshments. -

Arciiltecture

· BALBOA PARK· CENTRAL MESA PRECISE PLAN Precise Plan • Architecture ARCIIlTECTURE The goal of this section is to rehabilitate and modify the architecture of the Central Mesa ina manner which preserves its historic and aesthetic significance while providing for functional needs. The existing structures built for the 1915 and the 1935 Expositions are both historically and architecturally significant and should be reconstructed or rehabilitated. Not only should the individual structures be preserved, but the entire ensemble in its original composition should be preserved and restored wherever possible. It is the historic relationship between the built and the outdoor environment that is the hallmark of the two Expositions. Because each structure affects its site context to such a great degree, it is vital to the preservation of the historic district that every effort be made to preserve and restore original Exposition building footprints and elevations wherever possible. For this reason, emphasis has been placed on minimizing architectural additions unless they are reconstructions of significant historical features. Five major types of architectural modifications are recommended for the Central Mesa and are briefly described below. 1. Preservation and maintenance of existing structures. In the case of historically significant architecture, this involves preserving the historical significance of the structure and restoring lost historical features wherever possible. Buildings which are not historically significant should be preserved and maintained in good condition. 2. Reconstructions . This type of modification involves the reconstruction of historic buildings that have deteriorated to a point that prevents rehabilitation of the existing structure. This type of modification also includes the reconstruction of historically significant architectural features that have been lost. -

Alaska Beyond Magazine

The Past is Present Standing atop a sandstone hill in Cabrillo National Monument on the Point Loma Peninsula, west of downtown San Diego, I breathe in salty ocean air. I watch frothy waves roaring onto shore, and look down at tide pool areas harboring creatures such as tan-and- white owl limpets, green sea anemones and pink nudi- branchs. Perhaps these same species were viewed by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in 1542 when, as an explorer for Spain, he came ashore on the peninsula, making him the first person from a European ocean expedition to step onto what became the state of California. Cabrillo’s landing set the stage for additional Span- ish exploration in the 16th and 17th centuries, followed in the 18th century by Spanish settlement. When I gaze inland from Cabrillo National Monument, I can see a vast range of traditional Native Kumeyaay lands, in- cluding the hilly area above the San Diego River where, in 1769, an expedition from New Spain (Mexico), led by Franciscan priest Junípero Serra and military officer Gaspar de Portolá, founded a fort and mission. Their establishment of the settlement 250 years ago has been called the moment that modern San Diego was born. It also is believed to represent the first permanent European settlement in the part of North America that is now California. As San Diego commemorates the 250th anniversary of the Spanish settlement, this is an opportune time 122 ALASKA BEYOND APRIL 2019 THE 250TH ANNIVERSARY OF EUROPEAN SETTLEMENT IN SAN DIEGO IS A GREAT TIME TO EXPLORE SITES THAT HELP TELL THE STORY OF THE AREA’S DEVELOPMENT by MATTHEW J. -

Balboa Park Explorer Pass Program Resumes Sales Before Holiday Weekend More Participating Museums Set to Reopen for Easter Weekend

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Balboa Park Cultural Partnership Contact: Michael Warburton [email protected] Mobile (619) 850-4677 Website: Explorer.balboapark.org Balboa Park Explorer Pass Program Resumes Sales Before Holiday Weekend More Participating Museums Set to Reopen for Easter Weekend San Diego, CA – March 31 – The Balboa Park Cultural Partnership (BPCP) announced that today the parkwide Balboa Park Explorer Pass program has resumed the sale of day and annual passes, in advance of more museums reopening this Easter weekend and beyond. “The Explorer Pass is the easiest way to visit multiple museums in Balboa Park, and is a great value when compared to purchasing admission separately,” said Kristen Mihalko, Director of Operations for BPCP. “With more museums reopening this Friday, we felt it was a great time to restart the program and provide the pass for visitors to the Park.” Starting this Friday, April 2nd, the nonprofit museums available to visit with the Explorer Pass include: • Centro Cultural de la Raza, 3 days/week, open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday only • Japanese Friendship Garden, 7 days/week • San Diego Air and Space Museum, 7 days/week • San Diego Automotive Museum, 6 days/week, closed Monday • San Diego Model Railroad Museum, 3 days/week, open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday only • San Diego Museum of Art, 6 days/week, closed Wednesdays • San Diego Natural History Museum (The Nat), 5 days/week, closed Wednesday and Thursday The Fleet Science Center will rejoin the line up on April 9th; the Museum of Photographic Arts and the San Diego History Center will reopen on April 16th, and the Museum of Us will reopen on April 21st. -

MINUTES City of San Diego Park and Recreation Board BALBOA PARK

MINUTES City of San Diego Park and Recreation Board BALBOA PARK COMMITTEE November 6, 2008 Meeting held at: Mailing address is: Balboa Park Club, Santa Fe Room Balboa Park Administration 2150 Pan American Road 2125 Park Boulevard MS39 San Diego, CA 92101 San Diego, CA 92101-4792 ATTENDANCE: Members Present Members Absent Staff Present Jerelyn Dilno Jennifer Ayala Kathleen Hasenauer Vicki Granowitz Laurie Burgett Susan Lowery-Mendoza Mick Hager Mike Singleton Bruce Martinez Andrew Kahng David Kinney Mike McDowell Donald Steele (Arr. 5:40) CALL TO ORDER Chairperson Granowitz called the meeting to order at 5:37 P.M. APPROVAL OF MINUTES MSC IT WAS MOVED/SECONDED AND CARRIED UNANIMOUSLY TO APPROVE THE MINUTES OF THE OCTOBER 2, 2008 MEETING WITH CORRECTIONS TO REFLECT SINGLTON SECONDING ADOPTION ITEMS 201 AND 202 (KINNEY /DILNO 5-0) ABSTENTION- MCDOWELL REQUESTS FOR CONTINUANCES None NON AGENDA PUBLIC COMMENT Warren Simon, Chairperson of the Balboa Park Decembers Nights Committee, reported that there will be a few changes to this year’s venue. The Restaurant Taste will be located in the Palisades Parking lot adjacent to the Hall of Champions and a synthetic ice skating rink will also be located in the Palisades Parking Lot. The Plaza De Panama will host a spirits garden, and the Moreton Bay Fig Tree will be up-lighted. Shannon Sweeney representing Scott White Contemporary Art reported that the location approved by the Committee for the Bernar Venet sculpture requires a barrier to be placed around it for ADA compliance. Ms. Sweeney stated the barrier would detract from the sculpture and requested that the Committee reconsider placing the sculpture at the original requested location on the turf east of the San Diego Museum of Art. -

Casa Del Prado in Balboa Park

Chapter 19 HISTORY OF THE CASA DEL PRADO IN BALBOA PARK Of buildings remaining from the 1915 Panama-California Exposition, exhibit buildings north of El Prado in the agricultural section survived for many years. They were eventually absorbed by the San Diego Zoo. Buildings south of El Prado were gone by 1933, except for the New Mexico and Kansas Buildings. These survive today as the Balboa Park Club and the House of Italy. This left intact the Spanish-Colonial complex along El Prado, the main east-west avenue that separated north from south sections The Sacramento Valley Building, at the head of the Plaza de Panama in the approximate center of El Prado, was demolished in 1923 to make way for the Fine Arts Gallery. The Southern California Counties Building burned down in 1925. The San Joaquin Valley and the Kern-Tulare Counties Building, on the promenade south of the Plaza de Panama, were torn down in 1933. When the Science and Education and Home Economy buildings were razed in 1962, the only 1915 Exposition buildings on El Prado were the California Building and its annexes, the House of Charm, the House of Hospitality, the Botanical Building, the Electric Building, and the Food and Beverage Building. This paper will describe the ups and downs of the 1915 Varied Industries and Food Products Building (1935 Food and Beverage Building), today the Casa del Prado. When first conceived the Varied Industries and Food Products Building was called the Agriculture and Horticulture Building. The name was changed to conform to exhibits inside the building. -

Balboa Park Facilities

';'fl 0 BalboaPark Cl ub a) Timken MuseumofArt ~ '------___J .__ _________ _J o,"'".__ _____ __, 8 PalisadesBuilding fDLily Pond ,------,r-----,- U.,..p_a_s ..,.t,..._---~ i3.~------ a MarieHitchcock Puppet Theatre G BotanicalBuild ing - D b RecitalHall Q) Casade l Prado \ l::..-=--=--=---:::-- c Parkand Recreation Department a Casadel Prado Patio A Q SanD iegoAutomot iveMuseum b Casadel Prado Pat io B ca 0 SanD iegoAerospace Museum c Casadel Prado Theate r • StarlightBow l G Casade Balboa 0 MunicipalGymnasium a MuseumofPhotograph icArts 0 SanD iegoHall of Champions b MuseumofSan Diego History 0 Houseof PacificRelat ionsInternational Cottages c SanDiego Mode l RailroadMuseum d BalboaArt Conservation Cente r C) UnitedNations Bui lding e Committeeof100 G Hallof Nations u f Cafein the Park SpreckelsOrgan Pavilion 4D g SanDiego Historical Society Research Archives 0 JapaneseFriendship Garden u • G) CommunityChristmas Tree G Zoro Garden ~ fI) ReubenH.Fleet Science Center CDPalm Canyon G) Plaza deBalboa and the Bea Evenson Fountain fl G) HouseofCharm a MingeiInternationa l Museum G) SanDiego Natural History Museum I b SanD iegoArt I nstitute (D RoseGarden j t::::J c:::i C) AlcazarGarden (!) DesertGarden G) MoretonBay Ag T ree •........ ••• . I G) SanDiego Museum ofMan (Ca liforniaTower) !il' . .- . WestGate (D PhotographicArts Bui lding ■ • ■ Cl) 8°I .■ m·■ .. •'---- G) CabrilloBridge G) SpanishVillage Art Center 0 ... ■ .■ :-, ■ ■ BalboaPar kCarouse l ■ ■ LawnBowling Greens G 8 Cl) I f) SeftonPlaza G MiniatureRail road aa a Founders'Plaza Cl)San Diego Zoo Entrance b KateSessions Statue G) War MemorialBuil ding fl) MarstonPoint ~ CentroCu lturalde la Raza 6) FireAlarm Building mWorld Beat Cultura l Center t) BalboaClub e BalboaPark Activ ity Center fl) RedwoodBrid geCl ub 6) Veteran'sMuseum and Memo rial Center G MarstonHouse and Garden e SanDiego American Indian Cultural Center andMuseum $ OldG lobeTheatre Comp lex e) SanDiego Museum ofArt 6) Administration BuildingCo urtyard a MayS. -

Contents November Ballot for Voter President’S Message

President’s Message In the time leading up to November 8th, our We have a busy schedule supporters and I will be asking for YOUR help in ahead of us. Yes, I said spreading the word and voting to “Save SDHS.” “We.” For updated information on school activities, the football It will take all of us: schedule and the latest on how you can supporters at city hall, school help “Save SDHS,” visit our website at district supporters, SDHS www.sandiegohighschoolalumni.org. I hope to see you staff, students and alumni, to at a game, around town wearing your SDHS apparel, keep SDHS right where it’s at and spreading the word to “Save SDHS.” for another 100+ years. President’s Message (continued) on page 5 As I write this message, the city council approved by an 8 to 1 margin placing a city charter amendment on the Contents November ballot for voter President’s Message ..........................................................1 approval. SDHS CAP Committee ........................................................2 The amendment would authorize the city council to negotiate a lease agreement with the school district Editor’s Report ...................................................................3 for SDHS to remain in its current location. Gone But Not Forgotten ....................................................3 With the approval of the voters in November, the Historically Speaking: Fall Newsletter ..... Error! Bookmark legacy of SDHS will live on forever. The school will not defined. undergo planned facilities updates approved by voter’s years ago via a bond measure. Historically Speaking ......................................................4 It’s going to take all of us, and the committee that Annual All Classes Homecoming ........................................5 was formed in late July, to reach out to the San President’s Message (continued) .......................................5 Diego community to inform them of the benefits of having SDHS in its current location. -

St. Bartholomew's Church and Community House: Draft Nomination

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ST. BARTHOLOMEW’S CHURCH AND COMMUNITY HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: St. Bartholomew’s Church and Community House Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 325 Park Avenue (previous mailing address: 109 East 50th Street) Not for publication: City/Town: New York Vicinity: State: New York County: New York Code: 061 Zip Code: 10022 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): _X_ Public-Local: District: Public-State: Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 buildings sites structures objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 2 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: DRAFT NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ST. BARTHOLOMEW’S CHURCH AND COMMUNITY HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Inspired by Mexico: Architect Bertram Goodhue Introduces Spanish Colonial Revival Into Balboa Park

Inspired by Mexico: Architect Bertram Goodhue Introduces Spanish Colonial Revival into Balboa Park By Iris H.W. Engstrand G. Aubrey Davidson’s laudatory address to an excited crowd attending the opening of the Panama-California Exposition on January 1, 1915, gave no inkling that the Spanish Colonial architectural legacy that is so familiar to San Diegans today was ever in doubt. The buildings of this exposition have not been thrown up with the careless unconcern that characterizes a transient pleasure resort. They are part of the surroundings, with the aspect of permanence and far-seeing design...Here is pictured this happy combination of splendid temples, the story of the friars, the thrilling tale of the pioneers, the orderly conquest of commerce, coupled with the hopes of an El Dorado where life 1 can expand in this fragrant land of opportunity. G Aubrey Davidson, ca. 1915. ©SDHC #UT: 9112.1. As early as 1909, Davidson, then president of the Chamber of Commerce, had suggested that San Diego hold an exposition in 1915 to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal. When City Park was selected as the site in 1910, it seemed appropriate to rename the park for Spanish explorer Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, who had discovered the Pacific Ocean and claimed the Iris H. W. Engstrand, professor of history at the University of San Diego, is the author of books and articles on local history including San Diego: California’s Cornerstone; Reflections: A History of the San Diego Gas and Electric Company 1881-1991; Harley Knox; San Diego’s Mayor for the People and “The Origins of Balboa Park: A Prelude to the 1915 Exposition,” Journal of San Diego History, Summer 2010.