Charles the Bald: the Story of an Epithet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review Volume 11 (2011) Page 1

H-France Review Volume 11 (2011) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 11 (January 2011), No. 31 Karl Heidecker, The Divorce of Lothar II: Christian Marriage and Political Power in the Carolingian World, translated from the Dutch by Tanis M. Guest. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2010. x + 226 pp. Map, genealogical tables, bibliography, and index. $45.00 U.S. (cl.) ISBN 978- 0-8014-3929-2 Review by Sam Collins, George Mason University. Lothar II’s protracted attempt to divorce his wife Theutberga caused a European-wide scandal from 857 to his death in 869, and it is a scandal with an impressively large and detailed source base. In annals, conciliar acta, papal letters, charters, and, most importantly, an extensive tract devoted to the issue by Hincmar of Rheims, the story unfolds in frequently sordid detail. Lothar married Theutberga, a member of a prominent noble family, the so-called ‘Bosonids,’ in 855 for political advantage. What advantage this marriage offered the king seems soon to have departed, a process no doubt accelerated by Theutberga’s childlessness, and by 857 Lothar attempted a divorce from her and a return to his former partner (and possibly first wife), Waldrada, with whom he had a son. The grounds for the divorce were charges of the worst kind leveled at Theutberga: incest, sodomy, an abortion. Theutberga protested her innocence and either she or a proxy proved it through an ordeal of hot water in 858. Lothar, however, persisted, and in a trial at Aachen in 860 coerced Theutberga into a (false, or so many said) confession of her guilt. -

The Christian Martyr Movement of 850S Córdoba Has Received Considerable Scholarly Attention Over the Decades, Yet the Movement Has Often Been Seen As Anomalous

The Christian martyr movement of 850s Córdoba has received considerable scholarly attention over the decades, yet the movement has often been seen as anomalous. The martyrs’ apologists were responsible for a huge spike in evidence, but analysis of their work has shown that they likely represented a minority “rigorist” position within the Christian community and reacted against the increasing accommodation of many Mozarabic Christians to the realities of Muslim rule. This article seeks to place the apologists, and therefore the martyrs, in a longer-term perspective by demonstrating that martyr memories were cultivated in the city and surrounding region throughout late antiquity, from at least the late fourth century. The Cordoban apologists made active use of this tradition in their presentation of the events of the mid-ninth century. The article closes by suggesting that the martyr movement of the 850s drew strength from churches dedicated to earlier martyrs from the city and that the memories of the martyrs of the mid-ninth century were used to reinforce communal bonds at Córdoba and beyond in the following years. Memories and memorials of martyrdom were thus powerful means of forging connections across time and space in early medieval Iberia. Keywords Hagiography / Iberia, Martyrdom, Mozarabs – hagiography, Violence, Apologetics, Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain – martyrs, Eulogius of Córdoba, martyr, Álvaro de Córdoba, Paulo, author, Visigoths (Iberian kingdom) – hagiography In the year 549, Agila (d. 554), king of the Visigoths, took it upon himself to bring the city of Córdoba under his power. The expedition appears to have been an utter disaster and its failure was attributed by Isidore of Seville (d. -

Paschasius Radbertus and the Song of Songs

chapter 6 “Love’s Lament”: Paschasius Radbertus and the Song of Songs The Song of Songs was understood by many Carolingian exegetes as the great- est, highest, and most obscure of Solomon’s three books of wisdom. But these Carolingian exegetes would also have understood the Song as a dialogue, a sung exchange between Christ and his church: in fact, as the quintessential spiritual song. Like the liturgy of the Eucharist and the divine office, the Song of Songs would have served as a window into heavenly realities, offering glimpses of a triumphant, spotless Bride and a resurrected, glorified Bridegroom that ninth- century reformers’ grim views of the church in their day would have found all the more tantalizing. For Paschasius Radbertus, abbot of the great Carolingian monastery of Corbie and as warm and passionate a personality as Alcuin, the Song became more than simply a treasury of imagery. In this chapter, I will be examining Paschasius’s use of the Song of Songs throughout his body of work. Although this is necessarily only a preliminary effort in understanding many of the underlying themes at work in Paschasius’s biblical exegesis, I argue that the Song of Songs played a central, formative role in his exegetical imagina- tion and a structural role in many of his major exegetical works. If Paschasius wrote a Song commentary, it has not survived; nevertheless, the Song of Songs is ubiquitous in the rest of his exegesis, and I would suggest that Paschasius’s love for the Song and its rich imagery formed a prism through which the rest of his work was refracted. -

The Carolingian Past in Post-Carolingian Europe Simon Maclean

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 1 The Carolingian Past in Post-Carolingian Europe Simon MacLean On 28 January 893, a 13-year-old known to posterity as Charles III “the Simple” (or “Straightforward”) was crowned king of West Francia at the great cathedral of Rheims. Charles was a great-great-grandson in the direct male line of the emperor Charlemagne andclung tightly to his Carolingian heritage throughout his life.1 Indeed, 28 January was chosen for the coronation precisely because it was the anniversary of his great ancestor’s death in 814. However, the coronation, for all its pointed symbolism, was not a simple continuation of his family’s long-standing hegemony – it was an act of rebellion. Five years earlier, in 888, a dearth of viable successors to the emperor Charles the Fat had shattered the monopoly on royal authority which the Carolingian dynasty had claimed since 751. The succession crisis resolved itself via the appearance in all of the Frankish kingdoms of kings from outside the family’s male line (and in some cases from outside the family altogether) including, in West Francia, the erstwhile count of Paris Odo – and while Charles’s family would again hold royal status for a substantial part of the tenth century, in the long run it was Odo’s, the Capetians, which prevailed. Charles the Simple, then, was a man displaced in time: a Carolingian marooned in a post-Carolingian political world where belonging to the dynasty of Charlemagne had lost its hegemonic significance , however loudly it was proclaimed.2 His dilemma represents a peculiar syndrome of the tenth century and stands as a symbol for the theme of this article, which asks how members of the tenth-century ruling class perceived their relationship to the Carolingian past. -

LECTURE 5 the Origins of Feudalism

OUTLINE — LECTURE 5 The Origins of Feudalism A Brief Sketch of Political History from Clovis (d. 511) to Henry IV (d. 1106) 632 death of Mohammed The map above shows to the growth of the califate to roughly 750. The map above shows Europe and the East Roman Empire from 533 to roughly 600. – 2 – The map above shows the growth of Frankish power from 481 to 814. 486 – 511 Clovis, son of Merovich, king of the Franks 629 – 639 Dagobert, last effective Merovingian king of the Franks 680 – 714 Pepin of Heristal, mayor of the palace 714 – 741 Charles Martel, mayor (732(3), battle of Tours/Poitiers) 714 – 751 - 768 Pepin the Short, mayor then king 768 – 814 Charlemagne, king (emperor, 800 – 814) 814 – 840 Louis the Pious (emperor) – 3 – The map shows the Carolingian empire, the Byzantine empire, and the Califate in 814. – 4 – The map shows the breakup of the Carolingian empire from 843–888. West Middle East 840–77 Charles the Bald 840–55 Lothair, emp. 840–76 Louis the German 855–69 Lothair II – 5 – The map shows the routes of various Germanic invaders from 150 to 1066. Our focus here is on those in dark orange, whom Shepherd calls ‘Northmen: Danes and Normans’, popularly ‘Vikings’. – 6 – The map shows Europe and the Byzantine empire about the year 1000. France Germany 898–922 Charles the Simple 919–36 Henry the Fowler 936–62–73 Otto the Great, kg. emp. 973–83 Otto II 987–96 Hugh Capet 983–1002 Otto III 1002–1024 Henry II 996–1031 Robert II the Pious 1024–39 Conrad II 1031–1060 Henry I 1039–56 Henry III 1060–1108 Philip I 1056–1106 Henry IV – 7 – The map shows Europe and the Mediterranean lands in roughly the year 1097. -

Possibilities of Royal Power in the Late Carolingian Age: Charles III the Simple

Possibilities of royal power in the late Carolingian age: Charles III the Simple Summary The thesis aims to determine the possibilities of royal power in the late Carolingian age, analysing the reign of Charles III the Simple (893/898-923). His predecessors’ reigns up to the death of his grandfather Charles II the Bald (843-877) serve as basis for comparison, thus also allowing to identify mid-term developments in the political structures shaping the Frankish world toward the turn from the 9th to the 10th century. Royal power is understood to have derived from the interaction of the ruler with the nobles around him. Following the reading of modern scholarship, the latter are considered as partners of the former, participating in the royal decision-making process and at the same time acting as executors of these decisions, thus transmitting the royal power into the various parts of the realm. Hence, the question for the royal room for manoeuvre is a question of the relations between the ruler and the nobles around him. Accordingly, the analysis of these relations forms the core part of the study. Based on the royal diplomas, interpreted in the context of the narrative evidence, the noble networks in contact with the rulers are revealed and their influence examined. Thus, over the course of the reigns of Louis II the Stammerer (877-879) and his sons Louis III (879-882) and Carloman II (879-884) up until the rule of Charles III the Fat (884-888), the existence of first one, then two groups of nobles significantly influencing royal politics become visible. -

Introducing Civil Law Students to Common Law Legal Method Through Contract Law

641 Introducing Civil Law Students to Common Law Legal Method Through Contract Law Charles R. Calleros I. Introduction The Common Law Program at Université René Descartes in Paris introduces students trained in the civil law to common law doctrine and legal method through a series of English-language mini-courses offered every other week by visiting faculty from common law countries throughout the world. Beginning in the 2001–02 academic year through Fall, 2007, I had the honor and pleasure of teaching the opening course in this program.1 My pedagogic goals in this course included: • Introduce the students to fundamental elements of common law legal method in order to better prepare them for all the common law courses; • Use the issue of reciprocal inducement, within the common law doctrine of consideration, as both a vehicle for developing facility with legal method and as an exercise in comparative law; and • Expose students to both traditional and innovative American teaching techniques, as a further means of providing students with a comparative experience. To meet these goals, I led the students in a number of interactive exercises, some of them set in non-legal contexts so that the students focused all their attention on the legal method those exercises illustrated. Whether set in legal or non-legal contexts, these exercises required students to recognize and accept uncertainty in legal disputes, appreciate the role of stare decisis, and develop opposing arguments from facts and precedent. Others who teach the common law method to students from other legal traditions, either abroad or in U.S. -

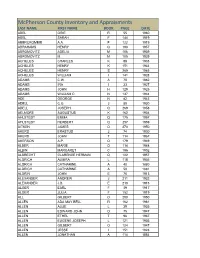

Mcpherson County Inventory and Appraisments LAST NAME FIRST NAME BOOK PAGE DATE ABEL ORIE R 55 1960 ABEL SARAH F 144 1919 ABERCROMBIE A.A

McPherson County Inventory and Appraisments LAST NAME FIRST NAME BOOK PAGE DATE ABEL ORIE R 55 1960 ABEL SARAH F 144 1919 ABERCROMBIE A.A. F 122 1919 ABRAHAMS HENRY Q 193 1957 ABROMOVITZ ADELIA M 106 1939 ABROMOVITZ M. M 105 1939 ACHILLES CHARLES K 88 1933 ACHILLES HENRY K 151 1934 ACHILLES HENRY S 289 1965 ACHILLES WILLIAM I 141 1928 ADAMS C.W. A 70 1882 ADAMS IRA I 33 1927 ADAMS JOHN H 129 1925 ADAMS WILLIAM C. N 147 1944 ADE GEORGE N 82 1943 ADELL C.G. J 80 1930 ADELL JOSEPH Q 269 1958 AELMORE AUGUSTUS K 162 1934 AHLSTEDT EMMA Q 175 1957 AHLSTEDT HERBERT Q 297 1959 AITKEN JAMES O 270 1950 AKERS ERASTUS J 74 1930 AKERS JOHN T 114 1967 AKERSON A.P. O 179 1949 ALBER MARIE O 114 1948 ALBIN MARGARET C 196 1902 ALBRECHT CLARENCE HERMAN Q 122 1957 ALDRICH ALMIRA L 118 1936 ALDRICH CATHARINE A 40 1880 ALDRICH CATHARINE A 50 1881 ALDRIN JOHN E 76 1913 ALEXANDER ANDREW J 211 1932 ALEXANDER J.B. E 210 1915 ALGER EARL F 39 1917 ALGER JULIA F 152 1919 ALL GILBERT O 290 1950 ALLEN ADA MAY BELL R 162 1961 ALLEN ALLIE L 39 1935 ALLEN EDWARD JOHN O 75 1947 ALLEN ETHEL T 96 1967 ALLEN EUGENE JOSEPH L 121 1936 ALLEN GILBERT O 124 1947 ALLEN JESSE I 151 1928 ALLEN JONATHAN A 114 1884 LAST NAME FIRST NAME BOOK PAGE DATE ALLEN LURA ELLEN Q 267 1958 ALLEN MARTHA C 174 1902 ALLEN NORMAN A 7 1878 ALLEN O.D. -

Charlemagne Empire and Society

CHARLEMAGNE EMPIRE AND SOCIETY editedbyJoamta Story Manchester University Press Manchesterand New York disMhutcdexclusively in the USAby Polgrave Copyright ManchesterUniversity Press2005 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chaptersbelongs to their respectiveauthors, and no chapter may be reproducedwholly or in part without the expresspermission in writing of both author and publisher. Publishedby ManchesterUniversity Press Oxford Road,Manchester 8113 9\R. UK and Room 400,17S Fifth Avenue. New York NY 10010, USA www. m an chestcru niversi rvp ress.co. uk Distributedexclusively in the L)S.4 by Palgrave,175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010,USA Distributedexclusively in Canadaby UBC Press,University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, CanadaV6T 1Z? British Library Cataloguing"in-PublicationData A cataloguerecord for this book is available from the British Library Library of CongressCataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 7088 0 hardhuck EAN 978 0 7190 7088 4 ISBN 0 7190 7089 9 papaluck EAN 978 0 7190 7089 1 First published 2005 14 13 1211 100908070605 10987654321 Typeset in Dante with Trajan display by Koinonia, Manchester Printed in Great Britain by Bell & Bain Limited, Glasgow IN MEMORY OF DONALD A. BULLOUGH 1928-2002 AND TIMOTHY REUTER 1947-2002 13 CHARLEMAGNE'S COINAGE: IDEOLOGY AND ECONOMY SimonCoupland Introduction basis Was Charles the Great - Charlemagne - really great? On the of the numis- matic evidence, the answer is resoundingly positive. True, the transformation of the Frankish currency had already begun: the gold coinage of the Merovingian era had already been replaced by silver coins in Francia, and the pound had already been divided into 240 of these silver 'deniers' (denarii). -

Glossar the Disintegration of the Carolingian Empire

Tabelle1 Bavaria today Germany’s largest state, located in the Bayern Southeast besiege, v surround with armed forces belagern Bretons an ethnic group located in the Northwest of Bretonen France Carpathian Mountains a range of mountains forming an arc of roughly Karpaten 1,500 km across Central and Eastern Europe, Charles the Fat (Charles III) 839 – 888, King of Alemannia from 876, King Karl III. of Italy from 879, Roman Emperor (as Charles III) from 881 Danelaw an area in England in which the laws of the Danelag Danes were enforced instead of the laws of the Anglo-Saxons Franconia today mainly a part of Bavaria, the medieval Franken duchy Franconia included towns such as Mainz and Frankfurt Henry I 876 – 936, the duke of Saxony from 912 and Heinrich I. king of East Francia from 919 until his death Huns a confederation of nomadic tribes that invaded Hunnen Europe around 370 AD Lombardy a region in Northern Italy Lombardei Lorraine a historical area in present-day Northeast Lothringen France, a part of the kingdom Lotharingia Lothar I (Lothair I) 795 – 855, the eldest son of the Carolingian Lothar I. emperor Louis I and his first wife Ermengarde, king of Italy (818 – 855), Emperor of the Franks (840 – 855) Lotharingia a kingdom in Western Europe, it existed from Lothringen 843 – 870; not to be confused with Lorraine Louis I (Louis the Pious 778 – 840, also called the Fair, and the Ludwig I. Debonaire; only surviving son of Charlemagne; King of the Franks Louis the German (Louis II) ca. 806 – 876, third son of Louis I, King of Ludwig der Bavaria (817 – 876) and King of East Francia Deutsche (843 – 876) Louis the Younger (Louis III) 835 – 882, son of Louis the German, King of Ludwig III., der Saxony (876-882) and King of Bavaria (880- Jüngere 882), succeeded by his younger brother, Charles the Fat, Magyars an ethnic group primarily associated with Ungarn Hungary. -

Complete Dissertation

University of Groningen The growth of an Austrasian identity Stegeman, Hans IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2014 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Stegeman, H. (2014). The growth of an Austrasian identity: Processes of identification and legend construction in the Northeast of the Regnum Francorum, 600-800. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 02-10-2021 The growth of an Austrasian identity Processes of identification and legend construction in the Northeast of the Regnum Francorum, 600-800 Proefschrift ter verkrijging van het doctoraat aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de rector magnificus dr. -

The Life and Times of Karola Szilvássy, Transylvanian Aristocrat and Modern Woman*

Cristian, Réka M.. “The Life and Times of Karola Szilvássy, A Transylvanian Aristocrat and Modern Woman.” Hungarian Cultural Studies. e-Journal of the American Hungarian Educators Association, Volume 12 (2019) DOI: 10.5195/ahea.2019.359 The Life and Times of Karola Szilvássy, Transylvanian Aristocrat and Modern Woman* Réka M. Cristian Abstract: In this study Cristian surveys the life and work of Baroness Elemérné Bornemissza, née Karola Szilvássy (1876 – 1948), an internationalist Transylvanian aristocrat, primarily known as the famous literary patron of Erdélyi Helikon and lifelong muse of Count Miklós Bánffy de Losoncz, who immortalized her through the character of Adrienne Milóth in his Erdélyi trilógia [‘The Transylvanian Trilogy’]. Research on Karola Szilvássy is still scarce with little known about the life of this maverick woman, who did not comply with the norms of her society. She was an actress and film director during the silent film era, courageous nurse in the World War I, as well as unusual fashion trendsetter, gourmet cookbook writer, Africa traveler—in short, a source of inspiration for many women of her time, and after. Keywords: Karola Szilvássy, Miklós Bánffy, János Kemény, Zoltán Óváry, Transylvanian aristocracy, modern woman, suffrage, polyglot, cosmopolitan, Erdélyi Helikon Biography: Réka M. Cristian is Associate Professor, Chair of the American Studies Department, University of Szeged, and Co-chair of the university’s Inter-American Research Center. She is author of Cultural Vistas and Sites of Identity: Literature, Film and American Studies (2011), co-author (with Zoltán Dragon) of Encounters of the Filmic Kind: Guidebook to Film Theories (2008), and general editor of AMERICANA E-Journal of American Studies in Hungary, as well as its e-book division, AMERICANA eBooks.