Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Analysis of the Process of Initial State Genesis in Rus' and Bulgaria

Comparative Analysis of the Process of Initial State Genesis in Rus' and Bulgaria Evgeniy A. Shinakov Svetlana G. Polyakova Bryansk State University ABSTRACT There has not been completed yet the typological research of Euro- pean polities' forms (of the complexity level of ‘barbarous’ state- hood, ‘complex chiefdoms’, and rarely – ‘early states’ – in terms of political anthropology), and of the pathways of their emergence. This research can be amplified with the study of the First Bulgar- ian kingdom before Omurtag's and Krum's reforms (the end of the 7th – the early 9th century) and synchronous to it complex chief- dom of ‘Rosia’ (in terms of Porphyrpgenitus) of the end of the 9th – mid-10th century. They have typological similarity in military and contractual character of pathways of state genesis (in ‘Rosia’ it is supplemented by foreign trade) as well as in the form of ‘barba- rous’ (pre-Christian) statehood. It has a multilevel – ‘federal’ – character. At the head there were the Turks-Bulgarians and the ‘Rhos’ (‘Ruses’), whose settlements had limited territory, the ‘slavini- yas’ with their own power structure were subordinated to them and supervised by the ‘federal’ power strong points. The ‘supreme’ power domination is supported not only by the fear of weapon, but also by the treaties based on reciprocity. The common interest was, for exam- ple, the participation in robbery of the Byzantine Empire and interna- tional trade. At first in a peaceful way, later with conflicts, Bulgaria was transformed into a unitarian territorial state by the reforms of the pagans Оmurtag and Krum, and then of the Christian Boris (the latter had led to the conflict within the top level of power – among the Turkic-Bulgarians aristocracy). -

By Uta Goerlitz — München the Emperor Charlemagne

Amsterdamer Beiträge zur alteren Germanistik 70 (2013), 195-208 Special Issue Section: Saints and Sovereigns KARL WAS AIN WÂRER GOTES WÎGANT 1 PROBLEMS OF INTERPRETING THE FIGURE OF CHARLEMAGNE IN THE EARLY MIDDLE HIGH GERMAN KAISERCHRONIK 2 by Uta Goerlitz — München Abstract The Kaiserchronik is the first German rhymed chronicle of the Roman Empire from Caesar to around 1150, fifteen years before Charlemagne’s canonization in 1165. A strand of scholarship that goes back to the middle of C19 sees the chronicle’s Charlemagne as an Emperor figure who is decidedly depicted as “German”. This cor- relates with the assumption, widespread in C19 and most of C20, based upon the erroneous equation of “Germanic” to “German”, that the historic Charlemagne was the first medieval “German” Emperor, an assumption debunked by historians in the last few decades. Readings of critics based on these faulty premises have neglected essential characteristics of this Early Middle High German text. One of these characteristics is Charlemagne’s saintly features, which implicitly contradict interpretations of the Emperor figure as a national hero. First, I question traditional interpretive patterns of Charlemagne in the Kaiserchronik. Then I re-examine the chronicle’s Charlemagne account, focusing, on the one hand, on the interferences between the descriptions of Charlemagne as a worldly ruler and, on the other, as a Christian Emperor with saintly characteristics. The Emperor Charlemagne (AD 800–814) was canonized in the year 1165, instigated by Emperor Frederic I Barbarossa and approved by the Antipope Paschal III. This event took place roughly a decade after the composition of the Early Middle High German Kaiserchronik, the central text of the following contribution. -

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

Possibilities of Royal Power in the Late Carolingian Age: Charles III the Simple

Possibilities of royal power in the late Carolingian age: Charles III the Simple Summary The thesis aims to determine the possibilities of royal power in the late Carolingian age, analysing the reign of Charles III the Simple (893/898-923). His predecessors’ reigns up to the death of his grandfather Charles II the Bald (843-877) serve as basis for comparison, thus also allowing to identify mid-term developments in the political structures shaping the Frankish world toward the turn from the 9th to the 10th century. Royal power is understood to have derived from the interaction of the ruler with the nobles around him. Following the reading of modern scholarship, the latter are considered as partners of the former, participating in the royal decision-making process and at the same time acting as executors of these decisions, thus transmitting the royal power into the various parts of the realm. Hence, the question for the royal room for manoeuvre is a question of the relations between the ruler and the nobles around him. Accordingly, the analysis of these relations forms the core part of the study. Based on the royal diplomas, interpreted in the context of the narrative evidence, the noble networks in contact with the rulers are revealed and their influence examined. Thus, over the course of the reigns of Louis II the Stammerer (877-879) and his sons Louis III (879-882) and Carloman II (879-884) up until the rule of Charles III the Fat (884-888), the existence of first one, then two groups of nobles significantly influencing royal politics become visible. -

Glossar the Disintegration of the Carolingian Empire

Tabelle1 Bavaria today Germany’s largest state, located in the Bayern Southeast besiege, v surround with armed forces belagern Bretons an ethnic group located in the Northwest of Bretonen France Carpathian Mountains a range of mountains forming an arc of roughly Karpaten 1,500 km across Central and Eastern Europe, Charles the Fat (Charles III) 839 – 888, King of Alemannia from 876, King Karl III. of Italy from 879, Roman Emperor (as Charles III) from 881 Danelaw an area in England in which the laws of the Danelag Danes were enforced instead of the laws of the Anglo-Saxons Franconia today mainly a part of Bavaria, the medieval Franken duchy Franconia included towns such as Mainz and Frankfurt Henry I 876 – 936, the duke of Saxony from 912 and Heinrich I. king of East Francia from 919 until his death Huns a confederation of nomadic tribes that invaded Hunnen Europe around 370 AD Lombardy a region in Northern Italy Lombardei Lorraine a historical area in present-day Northeast Lothringen France, a part of the kingdom Lotharingia Lothar I (Lothair I) 795 – 855, the eldest son of the Carolingian Lothar I. emperor Louis I and his first wife Ermengarde, king of Italy (818 – 855), Emperor of the Franks (840 – 855) Lotharingia a kingdom in Western Europe, it existed from Lothringen 843 – 870; not to be confused with Lorraine Louis I (Louis the Pious 778 – 840, also called the Fair, and the Ludwig I. Debonaire; only surviving son of Charlemagne; King of the Franks Louis the German (Louis II) ca. 806 – 876, third son of Louis I, King of Ludwig der Bavaria (817 – 876) and King of East Francia Deutsche (843 – 876) Louis the Younger (Louis III) 835 – 882, son of Louis the German, King of Ludwig III., der Saxony (876-882) and King of Bavaria (880- Jüngere 882), succeeded by his younger brother, Charles the Fat, Magyars an ethnic group primarily associated with Ungarn Hungary. -

From Charlemagne to Hitler: the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire and Its Symbolism

From Charlemagne to Hitler: The Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire and its Symbolism Dagmar Paulus (University College London) [email protected] 2 The fabled Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire is a striking visual image of political power whose symbolism influenced political discourse in the German-speaking lands over centuries. Together with other artefacts such as the Holy Lance or the Imperial Orb and Sword, the crown was part of the so-called Imperial Regalia, a collection of sacred objects that connotated royal authority and which were used at the coronations of kings and emperors during the Middle Ages and beyond. But even after the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the crown remained a powerful political symbol. In Germany, it was seen as the very embodiment of the Reichsidee, the concept or notion of the German Empire, which shaped the political landscape of Germany right up to National Socialism. In this paper, I will first present the crown itself as well as the political and religious connotations it carries. I will then move on to demonstrate how its symbolism was appropriated during the Second German Empire from 1871 onwards, and later by the Nazis in the so-called Third Reich, in order to legitimise political authority. I The crown, as part of the Regalia, had a symbolic and representational function that can be difficult for us to imagine today. On the one hand, it stood of course for royal authority. During coronations, the Regalia marked and established the transfer of authority from one ruler to his successor, ensuring continuity amidst the change that took place. -

World History Unit 1, Part Two, the Greeks and the Romans

World History Unit 3 – Medieval Europe, Renaissance, Reformation SSWH7 The student will analyze European medieval society with regard to culture, c. Explain the main characteristics of humanism; include the ideas of Petrarch, Dante, and politics, society, and economics. Erasmus. a. Explain the manorial system and feudalism; include the status of peasants and feudal d. Analyze the impact of the Protestant Reformation; include the ideas of Martin Luther monarchies and the importance of Charlemagne. and John Calvin. b. Describe the political impact of Christianity; include Pope Gregory VII and King e. Describe the Counter Reformation at the Council of Trent and the role of the Jesuits. Henry IV of Germany (Holy Roman Emperor). f. Describe the English Reformation and the role of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. c. Explain the role of the church in medieval society. g. Explain the importance of Gutenberg and the invention of the printing press. d. Describe how increasing trade led to the growth of towns and cities. SSWH13 The student will examine the intellectual, political, social, and economic SSWH9 The student will analyze change and continuity in the Renaissance and factors that changed the world view of Europeans. Reformation. a. Explain the scientific contributions of Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, and Newton and a. Explain the social, economic, and political changes that contributed to the rise of how these ideas changed the European world view. Florence and the ideas of Machiavelli. b. Identify the major ideas of the Enlightenment from the writings of Locke, Voltaire, and b. Identify artistic and scientific achievements of Leonardo da Vinci, the “Renaissance Rousseau and their relationship to politics and society. -

The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth

The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Adam R. Gustafson June 2011 © 2011 Adam R. Gustafson All Rights Reserved 2 This dissertation titled The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria by ADAM R. GUSTAFSON has been approved for the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts _______________________________________________ Dora Wilson Professor of Music _______________________________________________ Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT GUSTAFSON, ADAM R., Ph.D., June 2011, Interdisciplinary Arts The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria Director of Dissertation: Dora Wilson Drawing from a number of artistic media, this dissertation is an interdisciplinary approach for understanding how artworks created under the patronage of Albrecht V were used to shape Catholic identity in Bavaria during the establishment of confessional boundaries in late sixteenth-century Europe. This study presents a methodological framework for understanding early modern patronage in which the arts are necessarily viewed as interconnected, and patronage is understood as a complex and often contradictory process that involved all elements of society. First, this study examines the legacy of arts patronage that Albrecht V inherited from his Wittelsbach predecessors and developed during his reign, from 1550-1579. Albrecht V‟s patronage is then divided into three areas: northern princely humanism, traditional religion and sociological propaganda. -

THE TALISMAN of CHARLEMAGNE: NEW HISTORICAL and GEMOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES Gerard Panczer, Geoffray Riondet, Lauriane Forest, Michael S

FEATURE ARTICLES THE TALISMAN OF CHARLEMAGNE: NEW HISTORICAL AND GEMOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES Gerard Panczer, Geoffray Riondet, Lauriane Forest, Michael S. Krzemnicki, Davy Carole, and Florian Faure The gem-bearing reliquary known as the Talisman of Charlemagne is closely associated with the history of Europe. Its legend follows such figures as Charlemagne, Napoleon I, Empress Josephine, Hortense de Beauharnais, Napoleon III, and Empress Eugénie. This study provides new historical information collected in France, Germany, and Switzer- land about the provenance of this exceptional jewel, which contains a large glass cabochon on the front, a large blue-gray sapphire on the back, and an assortment of colored stones and pearls. The first scientific gemological analysis of this historical piece, carried out on-site at the Palace of Tau Museum in Reims, France, has made it possible to identify the colored stones and offer insight into their possible geographic origins. Based on our data and com- parison with similar objects of the Carolingian period, we propose that the blue-gray sapphire is of Ceylonese (Sri Lankan) origin, that the garnets originate from India or Ceylon, and that most of the emeralds are from Egypt except for one from the Habachtal deposit of Austria. The estimated weight of the center sapphire is approximately 190 ct, making it one of the largest known sapphires as of the early seventeenth century. he Talisman of Charlemagne is a sumptuous Chapelle in French) on February 28, 814 CE. Since jewel that has passed through the centuries. At the emperor did not leave specific instructions, his Tvarious times it has been said to contain frag- entourage decided to bury him in Aachen Cathedral ments of the hair of the Virgin Mary and a remnant (Minois, 2010). -

The Environmental History of Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site

CENTER FOR PUBLIC HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY The Environmental History of Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site Final Draft Elizabeth Michell July 31 2009 An abbreviated version intended as guide for visitors OYL/iJ INTRODUCTION On late spring day visitor stands on slight rise on the banks of Big Sandy Creek from where across Cheyenne chief Black Kettles village once stood whole lot of he nothing comments laconically It is quiet place its peacefulness giving it timeless But quality the visitor is wrong and the timelessness is deceptive You can never visit the past again The Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site is in southeastern fifteen Colorado about miles northeast of the small town of Eads This is high plains country dusty and flat the drab greens of grass and scrub melding into the relentless browns of desiccated vegetation sand and soil The surrounding landscape is crisscrossed dirt by trails and fence lines dotted with windmills outbuildings and stock watering tanks At the site groves of cottonwoods tower along the gently sloping banks of Big Sandy Creek in fact it would be difficult to follow the stream course without the line of trees For most of the year water does not flow and the creek bed is choked with sand sagebrushes and other the site dry prairie species Though is part of shortgrass most of the land is prairie actually sandy bottomland that may eventually become It in Black Kettles tallgrass prairie was dry time and it is still dry evident by how much more sagebrush species there are now -

Marking Systems

by Underhill® Marking Systems SPEED AND QUALITY OF PLAY…GOLF AS IT SHOULD BE. You know Grund Guide for making premier yardage marking solutions. Now backed with the strength of Underhill® distribution and product development, you can have the highest quality and most complete yardage marking systems available today and into the future. Sprinkler Head Yardage Markers Model SPM 106 - TORO Engraved FITS:Toro 730, 750, 760, 780, 830/850S, 834S, 835S, Caps: Perfect-fit caps engraved and color DT34/35S. 854S. DT54/55, 860S, 880S filled for high visibility. Multiple number locations COLORS: Caps - l/m/l/l vary for lids with holes. Numbers - m/l/l/l/l/l/l Model SPM 107 - Rain Bird FITS: Rain Bird E900, E950, E700, E750, E500, E550, Engraved Caps: Perfect fit caps engraved 700, 751, 51DR and color filled for high visibility number COLORS: Caps - l/m/l/l identification. Numbers - m/l/l/l/l/l/l/l Model SPM 110 - Hunter FITS: Hunter G800, G900, G90 Engraved Caps/Covers: Perfect-fit COLORS: Flange cover / caps - l flange covers (G800, G900) and caps (G90), Numbers - m/l/l/l/l/l/l engraved and color filled for high visibility. Model SPM 101 - Fit Over Discs: FITS: Toro 630, 650, 660, 670, 680, 690, 830/850S, Anodized aluminum (no paint!), these 834S, 835S, DT34/35, 854S, 855S, DT54/55, 860S, markers are engraved and custom fit to each 880S, Rain Bird 47/51 DR, 71/91/95, E900, E950, sprinkler. Multiple number locations vary for lids E700, E750, E500, E550, 1100, Hunter G-70/75, with holes. -

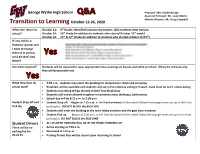

Transition to Learning October 12-26, 2020

George Wythe High School Principal: Mrs. Kimberly Ingo Assistant Principal: Mr. Jason Morris Athletic Director: Mr. Doug Campbell Transition to Learning October 12-26, 2020 When do I return to October 12: 9th Grade, identified-invitation by teacher, GED students, New Horizon school? October 19: 10th Grade (in addition to students who started October 12th week.) October 26: 11th & 12th Grade (in addition to students who started October 12/19th) If I my child is a Distance Learner and I want to change them to in person, can I do that? And When? Are mask required? Students will be required to wear appropriate face coverings on busses and while at school. If they do not have one, they will be provided one. What time does do 7:55 a.m. students may enter the building for temperature check and screening school start? Breakfast will be available and students will eat in the cafeteria eating 6 ft apart, mask must be worn unless eating. Students not eating will go directly to their first block class. Students will not be allowed to gather in commons areas (hallways, bathrooms) School day will be 8:15 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. Student Drop off and Student Drop off: Begins at 7:55 a.m. in the front entrance of the school follow the orange cones set up in the front Pick Up parking lot. DO NOT BLOCK the BUS LANE Students will enter the building at the main lobby entrance and the gym door entrance. Student Pick up: Begins at 2:00 p.m.