Estonian Art 1/2013 (32)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tallinn City Guidebook

www.infinitewalks.com Click icon to follow 11 top things to do in Tallinn, Estonia Published Date : August 24, 2020 Categories : Estonia Estonia, a small country in Northern Europe borders the Baltic Sea, Russia, and Latvia. Estonia’s capital Tallinn is quite famous for it’s well preserved medieval old town and it’s cathedrals. There are many things to do in Tallinn and the city is similar to any other European city. Tallinn was in my itinerary as a part of four country cruise trip (Stockholm — Tallinn — St. Petersburg — Helsinki — Stockholm). Pm2am were the organizers and it was their inaugural cruise trip too. 11 things to do in Tallinn 1. Free walking tour To know any European city, take a walking tour, especially in the old town. The tour guide gives a brief overview of the history, architecture, how the city was affected during war times, and many more insights. They show you places that even google maps can’t locate. Tallinn offers many free walking tours like the one from traveller, freetour. You just need to be on time at the meeting point and they take care of the rest. I also did a free walking tour in Warsaw and Belgrade. www.infinitewalks.com Click icon to follow The tour typically lasts 2 – 2.5 hours depending on your group size. Don’t forget to tip the guide at the end. Travel Tip: Do the tour on your first day and ask the guide for the best local food, things to do in the city, nightlife. It allows you to plan the vacation more efficiently. -

Download New Glass Review 17

NewGlass The Corning Museum of Glass NewGlass Review 17 The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 1996 Objects reproduced in this annual review Objekte, die in dieser jahrlich erscheinenden were chosen with the understanding Zeitschrift veroffentlicht werden, wurden unter that they were designed and made within der Voraussetzung ausgewahlt, dal3 sie inner- the 1995 calendar year. halb des Kalenderjahres 1995 entworfen und gefertigt wurden. For additional copies of New Glass Review, Zusatzliche Exemplare der New Glass Review please contact: konnen angefordert werden bei: The Corning Museum of Glass Sales Department One Museum Way Corning, New York 14830-2253 Telephone: (607) 937-5371 Fax: (607) 937-3352 All rights reserved, 1996 Alle Rechte vorbehalten, 1996 The Corning Museum of Glass The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 14830-2253 Corning, New York 14830-2253 Printed in Frechen, Germany Gedruckt in Frechen, Bundesrepublik Deutschland Standard Book Number 0-i 1-137-8 ISSN: 0275-469X Library of Congress Catalog Card Number Aufgefuhrt im Katalog der Library of Congress 81-641214 unter der Nummer 81-641214 Table of Contents/lnhalt Page/Seite Jury Statements/Statements der Jury 4 Artists and Objects/Kunstlerlnnen und Objekte 12 Some of the Best in Recent Glass 32 Bibliography/Bibliographie 40 A Selective Index of Proper Names and Places/ Ausgewahltes Register von Eigennamen und Orten 71 Jury Statements lthough Vermeer still outdraws Mondrian, it seems to me that many uch wenn Vermeer noch immer Mondrian aussticht, scheint mir, Amore people have come to enjoy both. In this particular age of AdaB es immer mehr Leute gibt, denen beide gefallen. -

Mass-Tourism Caused by Cruise Ships in Tallinn: Reaching for a Sustainable Way of Cruise Ship Tourism in Tallinn on a Social and Economic Level

Mass-tourism caused by cruise ships in Tallinn: Reaching for a sustainable way of cruise ship tourism in Tallinn on a social and economic level Tijn Verschuren S4382862 Master thesis Cultural Geography and Tourism Radboud University This page is intentionally left blank Mass-tourism caused by cruise ships in Tallinn: Reaching for a sustainable way of cruise ship tourism in Tallinn on a social and economic level Student: Tijn Verschuren Student number: s4382862 Course: Master thesis Cultural Geography and Tourism Faculty: School of Management University: Radboud University Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Huib Ernste Internship: Estonian Holidays Internship tutor: Maila Saar Place and date: 13-07-2020 Word count: 27,001 Preface In front of you lays my master thesis which was the final objective of my study of Cultural Geography and Tourism at the Radboud University. After years of studying, I can proudly say that I finished eve- rything and that I am graduated. My studying career was a quite a long one and not always that easy, but it has been a wonderful time where I have learned many things and developed myself. The pro- cess of the master thesis, from the beginning till the end, reflects these previous years perfectly. Alt- hough I am the one who will receive the degree, I could not have done this without the support and help of many during the years of studying in general and during the writing of this thesis in particular. Therefore I would like to thank the ones who helped and supported me. I want to start by thanking my colleagues at Estonian Holidays and especially Maila Saar, Lars Saar and Mari-Liis Makke. -

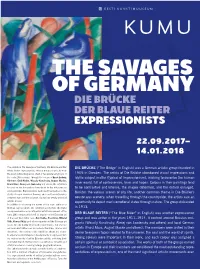

Die Brücke Der Blaue Reiter Expressionists

THE SAVAGES OF GERMANY DIE BRÜCKE DER BLAUE REITER EXPRESSIONISTS 22.09.2017– 14.01.2018 The exhibition The Savages of Germany. Die Brücke and Der DIE BRÜCKE (“The Bridge” in English) was a German artistic group founded in Blaue Reiter Expressionists offers a unique chance to view the most outstanding works of art of two pivotal art groups of 1905 in Dresden. The artists of Die Brücke abandoned visual impressions and the early 20th century. Through the oeuvre of Ernst Ludwig idyllic subject matter (typical of impressionism), wishing to describe the human Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke, Franz Marc, Alexej von Jawlensky and others, the exhibition inner world, full of controversies, fears and hopes. Colours in their paintings tend focuses on the innovations introduced to the art scene by to be contrastive and intense, the shapes deformed, and the details enlarged. expressionists. Expressionists dedicated themselves to the Besides the various scenes of city life, another common theme in Die Brücke’s study of major universal themes, such as the relationship between man and the universe, via various deeply personal oeuvre was scenery: when travelling through the countryside, the artists saw an artistic means. opportunity to depict man’s emotional states through nature. The group disbanded In addition to showing the works of the main authors of German expressionism, the exhibition attempts to shed light in 1913. on expressionism as an influential artistic movement of the early 20th century which left its imprint on the Estonian art DER BLAUE REITER (“The Blue Rider” in English) was another expressionist of the post-World War I era. -

The Soviet Woman in Estonian Art Jürgen Habermas

1 2010 1 Let’s refuse to be what we are (supposed to be)! Let’s Refuse to Be What We Are (Supposed to Be)! Airi Triisberg 5 Eva gives birth to earth Airi Triisberg Johannes Saar 7 Around the Golden Soldier Agne Narusyte 10 An artist and his double Anu Allas Based on the title Let’s Talk About Nationalism!, of identity is almost exclusively addressed as an it would be tempting to look at this exhibition* instrument for engendering normativity rather 13 Work-based solidarity is killed Interview with Eiki Nestor in relation to theories of public space, as it than a potential tool of empowerment that I is precisely the medium of talk that consti- find problematic in this context. At the same 16 Forum Marge Monko tutes a core notion in the liberal concept of time, it should also be noted that even the the public sphere, most notably elaborated by Habermasian definition of the public sphere 18 Art and Identity: The Soviet Woman in Estonian Art Jürgen Habermas. The curatorial statement by appears to be quite operative, insofar as it Michael Schwab Rael Artel seems to support the parallel with allows a conceptual distinction from the state 21 The queue as a social statement Habermas, insofar as it stresses the importance which has effectively been put to use in the Maria-Kristiina Soomre of contemporary art as a site for holding public framework of Let’s Talk About Nationalism! in 24 Five pictures of Flo Kasearu discussions. Nevertheless, the curator’s preoc- order to criticize the ideological and institu- Kaido Ole cupation with conflict actually indicates a dif- tional manifestations of the state. -

Wiiralti Kataloog 0.Pdf

Eduard Wiiralti galerii Eesti Rahvusraamatukogus The Eduard Wiiralt Gallery in the National Library of Estonia Tallinn 2015 Koostaja / Compile by Mai Levin Teksti autor / Text by Mai Levin Kujundaja / Designed by Tuuli Aule Toimetaja / Edited by Inna Saaret Tõlkija / Translated by Refiner Translations OÜ Endel Kõks. Eduard Wiiralti portree. Foto / Photograph: Teet Malsroos Esikaanel / On the front cover Tagakaanel / On the back cover Kataloogis esitatud teosed on digiteeritud Eesti Rahvusraamatukogu digiteerimiskeskuses. Works published in the Catalogue have been digitized by the National Library of Estonia. ISBN Autoriõigus / Copyright: Eesti Rahvusraamatukogu, 2015 National Library of Estonia, 2015 Eesti Autoriteühing, 2015 Estonian Authors’ Society, 2015 Trükkinud / Printed by Saateks FOREWORd Kristus pidulaua ääres, palvetava naise even started discussing this work as a pre- Mai Levin Mai Levin vari jt.), ent eelkõige haarab stseeni monition of war. Cabaret (initially titled dünaamilisus, ennastunustava naudingu The Dance of Life) was completed in 1931 1996. a. septembris avati Eesti Rahvus- In September 1996, the National Library ja iharuse atmosfäär. in Strasbourg, executed in the same tech- raamatukogus Eduard Wiiralti galerii – of Estonia opened the Eduard Wiiralt Eduard Wiiralt (1898–1954) sündis nique as its twin Inferno. The leading motif suure eesti graafiku teoste alaline ekspo- Gallery in the building – an extensive dis- Peterburi kubermangus Tsarskoje Seloo of Cabaret is sensuousness, triumphing sitsioon. See sai võimalikuks tänu Harry play of the great Estonian graphic artist. kreisis Gubanitsa vallas Robidetsi mõisas over everything intellectual. Here we can Männili ja Henry Radevalli Tallinna linnale This was made possible thanks to dona- mõisateenijate pojana. 1909. a. naases also notice symbolic details (the sleeping tehtud kingitusele, mis sisaldas 62 tions by Harry Männil and Henry Radevall perekond Eestisse, kus kunstniku isa sai Christ at the table, the shadow of a pray- E. -

Art Museum of Estonia Kumu Art Museum Press Release 2 December 2019

Art Museum of Estonia Kumu Art Museum Press release 2 December 2019 The largest exhibition of works by Estonian female artists will open at the Kumu Art Museum. On Thursday, 5 December at 5 pm, Emancipating Woman in Estonian and Finnish Art will open at the Kumu Art Museum. This is the largest exposition of artworks by Estonian female artists. It sheds light on a great deal of little-known material and establishes a dialogue with the works of Finnish female artists. The exhibition is the result of collaboration with the Ateneum Art Museum. During the Art Museum of Estonia’s 100th year of operation, Kumu has focused on female artists. This exhibition focuses on the changes in the self-awareness and social positions of women that started in the 19th century and are echoed in the activities of female artists, as well as in the way women are depicted. Works by Julie Hagen Schwarz, Sally von Kügelgen, Karin Luts, Natalie Mei, Lydia Mei, Aino Bach, Olga Terri, Maria Wiik, Helene Schjerfbeck, Sigrid Schauman, Elga Sesemann, Ellen Thesleff, Tove Jansson, Tuulikki Pietilä and others will be on display. Starting in the second half of the 20th century, more attention started to be paid to the works of female artists throughout the world. Prior to that, for various historical and social reasons, the works of female artists had often been viewed as secondary. Therefore, far fewer works by female artists than by men were included in art collections or exhibitions. And yet, the biographies and creative paths of many female artists confirm that women have not necessarily been the passive victims of social conditions, but have created opportunities for self- development. -

Estonian Academy of Sciences Yearbook 2018 XXIV

Facta non solum verba ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES YEARBOOK FACTS AND FIGURES ANNALES ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM ESTONICAE XXIV (51) 2018 TALLINN 2019 This book was compiled by: Jaak Järv (editor-in-chief) Editorial team: Siiri Jakobson, Ebe Pilt, Marika Pärn, Tiina Rahkama, Ülle Raud, Ülle Sirk Translator: Kaija Viitpoom Layout: Erje Hakman Photos: Annika Haas p. 30, 31, 48, Reti Kokk p. 12, 41, 42, 45, 46, 47, 49, 52, 53, Janis Salins p. 33. The rest of the photos are from the archive of the Academy. Thanks to all authos for their contributions: Jaak Aaviksoo, Agnes Aljas, Madis Arukask, Villem Aruoja, Toomas Asser, Jüri Engelbrecht, Arvi Hamburg, Sirje Helme, Marin Jänes, Jelena Kallas, Marko Kass, Meelis Kitsing, Mati Koppel, Kerri Kotta, Urmas Kõljalg, Jakob Kübarsepp, Maris Laan, Marju Luts-Sootak, Märt Läänemets, Olga Mazina, Killu Mei, Andres Metspalu, Leo Mõtus, Peeter Müürsepp, Ülo Niine, Jüri Plado, Katre Pärn, Anu Reinart, Kaido Reivelt, Andrus Ristkok, Ave Soeorg, Tarmo Soomere, Külliki Steinberg, Evelin Tamm, Urmas Tartes, Jaana Tõnisson, Marja Unt, Tiit Vaasma, Rein Vaikmäe, Urmas Varblane, Eero Vasar Printed in Priting House Paar ISSN 1406-1503 (printed version) © EESTI TEADUSTE AKADEEMIA ISSN 2674-2446 (web version) CONTENTS FOREWORD ...........................................................................................................................................5 CHRONICLE 2018 ..................................................................................................................................7 MEMBERSHIP -

Collecting Art in the Turmoil of War: Lithuania in 1939–1944 Collecting Art in the Turmoil of War: Lithuania in 1939–1944

Art History & Criticism / Meno istorija ir kritika 16 ISSN 1822-4555 (Print), ISSN 1822-4547 (Online) https://doi.org/10.2478/mik-2020-0003 Giedrė JANKEVIČIŪTĖ Vilnius Academy of Arts, Vilnius, Lithuania Osvaldas DAUGELIS M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art, Kaunas, Lithuania 35 COLLECTING ART IN THE TURMOIL OF WAR: LITHUANIA IN 1939–1944 COLLECTING ART IN THE TURMOIL OF WAR: LITHUANIA IN 1939–1944 IN LITHUANIA WAR: OF TURMOIL THE IN ART COLLECTING Summary. The article deals with the growth of the art collections of the Lithuanian national and municipal museums during WWII, a period traditionally seen as particularly unfavourable for cultural activities. During this period, the dynamics of Lithuanian museum art collections were maintained by two main sources. The first was caused by nationalist politics, or, more precisely, one of its priorities to support Lithuanian art by acquiring artworks from contemporaries. The exception to this strategy is the attention given to the multicultural art scene of Vilnius, partly Jewish, but especially Polish art, which led to the purchase of Polish artists’ works for the Vilnius Municipal Museum and the Vytautas the Great Museum of Culture in Kaunas, which had the status of a national art collection. The second important source was the nationalisation of private property during the Soviet occupation of 1940–1941. This process enabled the Lithuanian museums to enrich their collections with valuable objets d’art first of all, but also with paintings, sculptures and graphic prints. Due to the nationalisation of manor property, the collections of provincial museums, primarily Šiauliai Aušra and Samogitian Museum Alka in Telšiai, significantly increased. -

TARTU ÜLIKOOLI VILJANDI KULTUURIAKADEEMIA Rahvusliku Käsitöö Osakond Rahvusliku Tekstiili Eriala Karin Vetsa HARJUMAA PÕIME

TARTU ÜLIKOOLI VILJANDI KULTUURIAKADEEMIA Rahvusliku käsitöö osakond Rahvusliku tekstiili eriala Karin Vetsa HARJUMAA PÕIMEVAIPADE KOMPOSITSIOONILISED TÜÜBID 19. SAJANDIL – 20. SAJANDI 30-NDATEL AASTATEL. KOOPIAVAIP EESTI VABAÕHUMUUSEUMILE Diplomitöö Juhendaja: Riina Tomberg, MA Kaitsmisele lubatud .............................. Viljandi 2012 SISUKORD SISSEJUHATUS.............................................................................................................................................................................3 1. HARJUMAA TELGEDEL KOOTUD VAIPADE KUJUNEMINE.......................................................................................5 1.1 AJALOOLISE HARJUMAA TERRITOORIUM .............................................................................................................5 1.2 VAIBA NIMETUSE KUJUNEMINE ............................................................................................................................6 1.3 VAIBA FUNKTSIOONIDE KUJUNEMINE ..................................................................................................................7 1.4 VAIPADE KAUNISTAMISE MÕJUTEGURID ..............................................................................................................8 1.5 TELGEDEL KOOTUD VAIPADE TEHNIKATE KUJUNEMINE .....................................................................................10 2. HARJUMAA PÕIMEVAIPADE TEHNIKAD ......................................................................................................................12 -

City Break 100 Free Offers & Discounts for Exploring Tallinn!

City Break 100 free offers & discounts for exploring Tallinn! Tallinn Card is your all-in-one ticket to the very best the city has to offer. Accepted in 100 locations, the card presents a simple, cost-effective way to explore Tallinn on your own, choosing the sights that interest you most. Tips to save money with Tallinn Card Sample visits with Normal 48 h 48 h Tallinn Card Adult Tallinn Price Card 48-hour Tallinn Card - €32 FREE 1st Day • Admission to 40 top city attractions, including: Sightseeing tour € 20 € 0 – Museums Seaplane Harbour (Lennusadam) € 10 € 0 – Churches, towers and town wall – Tallinn Zoo and Tallinn Botanic Garden Kiek in de Kök and Bastion Tunnels € 8,30 € 0 – Tallinn TV Tower and Seaplane Harbour National Opera Estonia -15% € 18 € 15,30 (Lennusadam) • Unlimited use of public transport 2nd Day • One city sightseeing tour of your choice Tallinn TV Tower € 7 € 0 • Ice skating in Old Town • Bicycle and boat rental Estonian Open Air Museum with free audioguide € 15,59 € 0 • Bowling or billiards Tallinn Zoo € 5,80 € 0 • Entrance to one of Tallinn’s most popular Public transport (Day card) € 3 € 0 nightclubs • All-inclusive guidebook with city maps Bowling € 18 € 0 Total cost € 105,69 € 47,30 DISCOUNTS ON *Additional discounts in restaurants, cafés and shops plus 130-page Tallinn Card guidebook • Sightseeing tours in Tallinn and on Tallinn Bay • Day trips to Lahemaa National Park, The Tallinn Card is sold at: the Tallinn Tourist Information Centre Naissaare and Prangli islands (Niguliste 2), hotels, the airport, the railway station, on Tallinn-Moscow • Food and drink in restaurants, bars and cafés and Tallinn-St. -

Tartu Ülikooli Muuseum 2016

TARTU ÜLIKOOLI MUUSEUM 2016 TARTU ÜLIKOOLI MUUSEUM ARUANNE 2016 Tartu Ülikooli Muuseum 2 SISUKORD 1 SISSEJUHATUS ............................................................................................................................................ 4 2 MUUSEUM ARVUDES ................................................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Personal 31.detsembri 2016 seisuga töötas muuseumis 39 inimest (täidetud ametikohti 29,45). ........ 6 2.2 Põhifondi suurus 31.12.2016 – 103 703 museaali ................................................................................ 6 2.3 Eelarve (allikas TÜ rahandusosakond) .................................................................................................. 6 2.4 Külastajad .............................................................................................................................................. 6 3 MUUSEUMIKÜLASTUSTE STATISTIKA ................................................................................................. 7 4 OMATULU ................................................................................................................................................... 10 5 EKSPOSITSIOON JA NÄITUSED .............................................................................................................. 13 5.1 Aastanäitus, sh satelliitnäitused ................................................................................................................... 13 5.2 Ühekordsed näituseprojektid