To Be Or Not to Be

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SM 9 the Methods of Ethnology

Savage Minds Occasional Papers No. 9 The Methods of Ethnology By Franz Boas Edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub First edition, 18 January, 2014 Savage Minds Occasional Papers 1. The Superorganic by Alfred Kroeber, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 2. Responses to “The Superorganic”: Texts by Alexander Goldenweiser and Edward Sapir, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 3. The History of the Personality of Anthropology by Alfred Kroeber, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 4. Culture and Ethnology by Robert Lowie, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 5. Culture, Genuine and Spurious by Edward Sapir, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 6. Culture in the Melting-Pot by Edward Sapir, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 7. Anthropology and the Humanities by Ruth Benedict, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 8. Configurations of Culture in North America, by Ruth Benedict, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub 9. The Methods of Ethnology, by Franz Boas, edited and with an introduction by Alex Golub Copyright information This original work is copyright by Alex Golub, 2013. The author has issued the work under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States license. You are free • to share - to copy, distribute and transmit the work • to remix - to adapt the work Under the following conditions • attribution - you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author • noncommercial - you may not use this work for commercial purposes • share alike - if you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one This work includes excerpts from Boas, Franz. -

1 the Politics of Ethnopoetics by Gary Snyder This “Politics” Is

1 The Politics of Ethnopoetics by Gary Snyder This \politics" is fundamentally the question of what occidental and indus- trial technological civilization is doing to the earth. The earth: (I'm just going to remind us of a few facts), is 57 million square miles, 3.7 billion human be- ings, evolved over the last 4 million years; plus, 2 million species of insects, 1 million species of plants, 20 thousand species of fish, and 8,700 species of birds; constructed out of 97 naturally occurring surface elements with the power of the annual solar income of the sun. That is a lot of diversity. Yesterday, (who was it), David Antin, I believe, told how the Tragedians asked Plato to let them put on some tragedies. Plato said, \Very interesting, gentlemen, but I must tell you something. We have prepared here the greatest tragedy of all. It is called The State." From a very early age I found myself standing in an undefinable awe before the natural world. An attitude of gratitude, wonder, and a sense of protection especially as I began to see the hills being bulldozed down for roads, and the forests of the Pacific Nothwest magically float away on logging trucks. I grew up in a rural family in the state of Washington. My grandfather was a homesteader in the Pacific Northwest. The economic base of the whole region was logging. In trying to grasp the dynamics of what was happening, rural state of Washington, 1930's, depression, white boy out in the country, German on one side, Scotch- Irish on the other side, radical, that is to say, sort of grass roots Union, I.W.W., and socialist-radical parents, I found nothing in their orientation, (critical as it was of American politics and economics), that could give me an access to understanding what was happening. -

Report of the Working Group on Exonyms Conference

Eleventh United Nations Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names New York, 8-17 August 2017 Item 11 of the provisional agenda Exonyms Report of the Working Group on Exonyms Submitted by the Working Group on Exonyms Prepared by Peter Jordan (Austria), Convenor, Working Group on Exonyms - 1 - Summary The report highlights the activities of the UNGEGN Working Group on Exonyms (WGE) since the 10th United Nations Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names (UNCSGN) in 2012. In this period, the Working Group held three business meetings and four workshops and published four books of proceedings. The WG met on August 6, 2012 during the 10th Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names in the UN Headquarters in New York and discussed the endonym/ exonym divide and new definitions of the endonym and the exonym as well as the question whether a third term for international waters is needed. At the same occasion, Peter JORDAN was confirmed as WG convenor by elections. The WG met again for its 14th meeting in Corfu, Greece, 23-25 May 2013. It had the character of a workshop and was organized in conjunction with a meeting of the UNGEGN Working Group on Toponymic Terminology (Convenor: Staffan NYSTRÖM). The meeting of the WGE was attended by 33 experts from 20 countries and saw 17 paper presentations on the endonym/exonym divide as well as on use and documentation of exonyms in various countries. This sequence of paper presentations was followed by an intensive discussion on new definitions of the endonym and the exonym. Proceedings of the 14th Meeting have been published as Vol. -

Ethnography, Cultural and Social Anthropology

UC Berkeley Anthropology Faculty Publications Title Ethnography, Cultural and Social Anthropology Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9t13v9kz Journal American Anthropologist, 55(4) Author Lowie, Robert H. Publication Date 1953-10-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ETHNOGRAPHY, CULTURAL AND SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY By ROBERT H. LOWIE HE discussion by Professors Murdock and Firth, Professor Fortes's T contribution to the debate, Professor Radcliffe-Brown's illuminating letter in a recent issue of this journal, and a number of other statements by American and British colleagues (Murdock 1951; Firth 1951; Radcliffe-Brown 1952; Fortes 1953; Evans-Pritchard 1951) stimulate reflections on cultural and social anthropology. In the present, wholly uncontroversial article I shall first define the aims of cultural anthropology as I understand them and shall then inquire intQ the relations of that discipline with social anthropology as defined by British scholars. I Whatever differences may divide cultural from social anthropologists, they are hardly greater than those which divide self-styled cultural anthropologists. IndeedJ I should say that many of us feel incomparably closer to the English anthropologists referred to above than, say, to Goldenweiser in his later phases. A concrete example will illustrate the issue. In one of his books (Golden weiser 1922) this writer devotes a chapter to the Baganda, relying as he was bound to do on Roscoe's well-known work. He tells us that "maize is perhaps the principal staple food, but plantain trees are also cultivated on a large scale." Now the primary source (Roscoe 1911: 5, 432) states in unmistakable terms that plantains "furnish their staple food," whereas maize "was never grown in any quantity .. -

Ethnomusicology a Very Short Introduction

ETHNOMUSICOLOGY A VERY SHORT INTRODUCTION Thimoty Rice Sumário Chapter 1 – Defining ethnomusicology...........................................................................................4 Ethnos..........................................................................................................................................5 Mousikē.......................................................................................................................................5 Logos...........................................................................................................................................7 Chapter 2 A bit of history.................................................................................................................9 Ancient and medieval precursors................................................................................................9 Exploration and enlightenment.................................................................................................10 Nationalism, musical folklore, and ethnology..........................................................................10 Early ethnomusicology.............................................................................................................13 “Mature” ethnomusicology.......................................................................................................15 Chapter 3........................................................................................................................................17 Conducting -

Anthropology, History Of

Encyclopedia of Race and Racism, Vol1 – finals/ 10/4/2007 11:59 Page 93 Anthropology, History of Jefferson, Thomas. 1944. ‘‘Notes on the State of Virginia.’’ In defend that institution from religious abolitionists, who The Life and Selected Writings of Thomas Jefferson, edited by called for the unity of God’s children, and from Enlight- Adrienne Koch and William Peden. New York: Modern enment critics, who called for liberty, fraternity, and American Library. equality of man. During the early colonial experience in Lewis, R. B. 1844. Light and Truth: Collected from the Bible and Ancient and Modern History Containing the Universal History North America, ‘‘race’’ was not a term that was widely of the Colored and Indian Race; from the Creation of the World employed. Notions of difference were often couched in to the Present Time. Boston: Committee of Colored religious terms, and comparisons between ‘‘heathen’’ and Gentlemen. ‘‘Christian,’’ ‘‘saved’’ and ‘‘unsaved,’’ and ‘‘savage’’ and Morton, Samuel. 1844. Crania Aegyptiaca: Or, Observations on ‘‘civilized’’ were used to distinguish African and indige- Egyptian Ethnography Derived from Anatomy, History, and the nous peoples from Europeans. Beginning in 1661 and Monuments. Philadelphia: J. Penington. continuing through the early eighteenth century, ideas Nash, Gary. 1990. Race and Revolution. Madison, WI: Madison about race began to circulate after Virginia and other House. colonies started passing legislation that made it legal to Pennington, James, W. C. 1969 (1841). A Text Book of the enslave African servants and their children. Origins and History of the Colored People. Detroit, MI: Negro History Press. In 1735 the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus com- pleted his first edition of Systema Naturae, in which he attempted to differentiate various types of people scientifi- Mia Bay cally. -

Hymes's Linguistics and Ethnography in Education

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons GSE Faculty Research Graduate School of Education 1-2009 Hymes's Linguistics and Ethnography in Education Nancy H. Hornberger University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Hornberger, N. H. (2009). Hymes's Linguistics and Ethnography in Education. Text & Talk: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Language, Discourse & Communication Studies, 29 (3), 347-358. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/TEXT.2009.018 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs/246 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hymes's Linguistics and Ethnography in Education Abstract Education is one of the arenas in which Hymes has brought his scholarship and politics of advocacy to bear in the world, perhaps most visibly through his University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education deanship (1975–1987), but also through the scope and depth of his writings on linguistics and ethnography in education. Language inequality is an enduring theme of Hymes's work, in relation not only to Native American ethnopoetics, narrative analysis, and linguistic socialization, but also to educational linguistics and ethnography in education. Hymes proposed a vision and a set of ways of doing educational linguistics and ethnography in education—from ethnographic monitoring and ethnography of communication to ethnopoetics of oral narrative and ethnography of language policy—that have inspired and informed researchers for a generation and more. Keywords communicative competence, educational linguistics, ethnopoetics, language inequality, language planning, linguistic socialization Disciplines Education This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs/246 Hymes’s linguistics and ethnography in education* NANCY H. -

The Semantic Field of Genocide, Cultural Genocide, and Ethnocide in Indigenous Rights Discourse

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 9 Issue 2 Time, Movement, and Space: Genocide Article 6 Studies and Indigenous Peoples 10-2015 What Does Genocide Produce? The Semantic Field of Genocide, Cultural Genocide, and Ethnocide in Indigenous Rights Discourse Jeff Benvenuto Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Benvenuto, Jeff (2015) "What Does Genocide Produce? The Semantic Field of Genocide, Cultural Genocide, and Ethnocide in Indigenous Rights Discourse," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 9: Iss. 2: 26-40. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.9.2.1302 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol9/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What Does Genocide Produce? The Semantic Field of Genocide, Cultural Genocide, and Ethnocide in Indigenous Rights Discourse Jeff Benvenuto Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey Newark, NJ, USA Abstract: The semantic field of genocide, cultural genocide, and ethnocide overlaps between Indigenous rights discourse and genocide studies. Since the 1970s, such language has been used to express grievances that have stimulated the construction of Indigenous rights in international law. These particular words signify general concerns with the integrity of Indigenous peoples, thereby undergirding a larger framework of normative beliefs, ethical arguments, and legal claims, especially the right to self-determination. -

Language and Place Names in National and Regional Atlases. Methodological Considerations and Practical Use Exemplified by New Atlases from the Eastern Part of Europe

LANGUAGE AND PLACE NAMES IN NATIONAL AND REGIONAL ATLASES. METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS AND PRACTICAL USE EXEMPLIFIED BY NEW ATLASES FROM THE EASTERN PART OF EUROPE Peter Jordan Austrian Institute of East and Southeast European Studies, Vienna Abstract National and regional atlases are mainly conceived for national use, but as map works with a representative function they address, in contrast to school atlases, also an international audience. Taking this into account, many of them use for titles, legends and explanatory texts not only the national language, but also one or more world languages or are published in different language editions. The use of a second or third editorial language has, however, implications on the treatment of place names, especially on the use of exonyms. Another aspect deriving from the atlases’ representative function is the reflection of minority names. The paper investigates into relevant practices applied in recently published national and regional atlases from the eastern part of Europe and offers some methodological considerations as regards the use of more than one editorial language, the use of exonyms in this case as well the use of minority names. 1 INTRODUCTION National and regional atlases are mainly conceived for national use. But as map works with a representative function they address, in contrast to school atlases, also an international audience. Taking this into account, many of them use for titles, legends and explanatory texts not only the national language, but also one or more world languages or are published in different language editions. The use of a second or even more editorial languages has, however, implications on the treatment of place names. -

The Legacy of Dell Hymes: Ethnopoetics, Narrative Inequality

Book Reviews 111 grown up around the assassination of JFK, the Not only does Lepselter argue her thesis in events of 9/11, and the annual meetings of scholarly terms but, in the process, she also tells world leaders known as the Bilderberg Group, a good story in a literary vein, which makes the to mention only a few. But there is a continuum book not only worthwhile for understanding in this process, in the search for solutions to an interesting aspect of American culture, but problems that are masked by conventional wis- also a pleasure to read. dom and custom: a quest that ranges from the uncanny on one end through the typical con- spiracy theory to the other end of the contin- The Legacy of Dell Hymes: Ethnopoetics, uum, where we find the valuable processes of Narrative Inequality, and Voice. Ed. Paul V. connecting dots and thinking out of the box. Kroskrity and Anthony K. Webster. (Blooming- Here, Lepselter moves her ethnographic lens to ton: Indiana University Press, 2015. Pp. 291, Rachel, Nevada, near Area 51, where she introduction, index.) worked as a waitress in order to talk to believers who came to what she calls the “geographic fo- John H. McDowell cus of the uncanny American conspiracy the- Indiana University ory” (p. 80). She ends with a coda, titled “One More What we have here is a smorgasbord of lively Thing.” Here, she tells her own story, which il- work that revisits and extends the legacy of Dell lustrates how immersion in such narratives, Hymes, that resolute Oregonian who consoli- which are supported on all sides by earnest be- dated ethnopoetics to recognize eloquent voices lievers, can color one’s perception and emotion. -

01 D.But Partie Groupe GB

Our strengths combined I 2003 annual report Crédit Agricole S.A. 2003 annual report Crédit Agricole S.A. A French limited company with a share capital of € 4,420,567,311 Paris Trade and Company Registry No. 784 608 416 91-93, boulevard Pasteur - 75015 Paris - France Tel. 33 (0) 1 43 23 52 02 www.credit-agricole-sa.fr 2.7375.9 - DRI/03 The Crédit Agricole group > Our strengths combined Combining power with proximity, unity with decentralisation I 2003 business review • Profile I 1 • Message from the Chairman and the Chief Executive Officer I 2 • A powerful Group I 4 2003, an ambitious project becomes reality • 2003 key figures I 6 • Corporate governance I 8 • Crédit Agricole S.A. group Management I 12 • 2003 review of operations I 14 • French retail banking – Regional Banks I 16 • French retail banking – Crédit Lyonnais I 26 • Specialised financial services I 34 • Asset management, insurance and private banking I 44 • Corporate and investment banking I 54 • International retail banking I 64 • Sustainable development I 68 Solidarity and commitment to society Human resources and relations Customer and supplier relations Environmental protection Crédit Agricole S.A. share data • Summary chart of subsidiaries and affiliates I 92 Crédit Agricole S.A. 2003 annual report • Crédit Agricole group I 94 Summary balance sheet and income statement Addresses and management of the Regional Banks Crédit Agricole S.A. A French limited company with a share capital of € 4,420,567,311 Paris Trade and Company Registry No. 784 608 416 AMF Only the French language version of the shelf-registration document has been submitted to the AMF. -

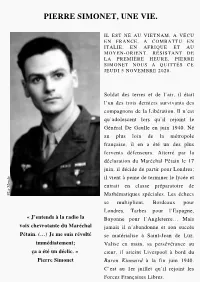

Décès De Pierre Simonet, Elysée

PIERRE SIMONET, UNE VIE. IL EST NÉ AU VIETNAM, A VÉCU EN FRANCE, A COMBATTU EN ITALIE, EN AFRIQUE ET AU MOYEN-ORIENT. RÉSISTANT DE LA PREMIÈRE HEURE, PIERRE SIMONET NOUS A QUITTÉS CE JEUDI 5 NOVEMBRE 2020. Soldat des terres et de l’air, il était l’uN des trois derNiers survivaNts des compagNoNs de la LibératioN. Il N’est qu’adolesceNt lors qu’il rejoiNt le GéNéral De Gaulle eN juiN 1940. Né au plus loiN de la métropole fraNçaise, il eN a été uN des plus ferveNts défeNseurs. Atterré par la déclaratioN du Maréchal PétaiN le 17 juiN, il décide de partir pour LoNdres; e il vieNt à peiNe de termiNer le lycée et d N o eNtrait eN classe préparatoire de M e L Mathématiques spéciales. Les échecs © se multiplieNt, Bordeaux pour LoNdres, Tarbes pour l’EspagNe, « J’eNteNds à la radio la BayoNNe pour l’ANgleterre… Mais voix chevrotaNte du Maréchal jamais il N’abaNdoNNe et soN succès PétaiN. (…) Je me suis révolté se matérialise à SaiNt-JeaN de Luz. immédiatemeNt; Valise eN maiN, sa persévéraNce au ça a été uN déclic. » cœur, il atteiNt Liverpool à bord du Pierre SimoNet BaroN KiNNaird à la fiN juiN 1940. C’est au 1er juillet qu’il rejoiNt les Forces FraNçaises Libres. A défaut d’eNtrer daNs l’aviatioN -il N’a positioNs soNt duremeNt attaquées et alors pas le brevet de pilote- il est affecté que le capitaiNe de l’opératioN a ordre daNs l’Artillerie FFL, alors eN cours de de partir, SimoNet Ne quitte soN poste créatioN.