Committee for Development Planning Report on the Seventh Session

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Be Or Not to Be

P ie r r e L e R o u x Institut de Recherche sur le Sud-Est Asiatique, CNRS France To Be or Not to B e... The Cultural Identity of the Jawi (Thailand) Abstract At the beginning of the century, the sultanate of Patani was permanently annexed by Siam (Thailand), and its inhabitants were cut off from a common future with Malaysia. Since then, these people, Muslims of Malay origin, have resisted political and cultural integration, maintaining themselves as Malays vis-a-vis the Thai and distinguishing themselves from other Malays in elaborating an autonym, the usage of which is somewhat of a puzzle to those outside the community. But in this way it seems an appropriate mark of identification for the Jawi: existing, but much debated; used, but not recognized; in short, in a state of limbo. Key words: Jawi— Thailand— Malaysia— ethnicity— autonym— endonym— exonym Asian Folklore Studies, Volume 57, 1998: 223-255 A national unity can be achieved through a diversity of ethnic groups. No cultural group would submit to a process of integration that would eventually lead to the loss of its valued identity. SURIN PlTSUWAN, Islam and Malay Nationalism T the southeastern extremity of peninsular Thailand there are four provinces whose inhabitants, about two million people, make A up close to 4% Thailand’s population. They are of Malay origin, fol low the Muslim religion, and represent four-fifths of the Muslims of Thailand. They are the second-largest minority after the Chinese, and call themselves the “Jawi.” These provinces are Pattani,Yala,Narathiwat,and Satun. -

01 D.But Partie Groupe GB

Our strengths combined I 2003 annual report Crédit Agricole S.A. 2003 annual report Crédit Agricole S.A. A French limited company with a share capital of € 4,420,567,311 Paris Trade and Company Registry No. 784 608 416 91-93, boulevard Pasteur - 75015 Paris - France Tel. 33 (0) 1 43 23 52 02 www.credit-agricole-sa.fr 2.7375.9 - DRI/03 The Crédit Agricole group > Our strengths combined Combining power with proximity, unity with decentralisation I 2003 business review • Profile I 1 • Message from the Chairman and the Chief Executive Officer I 2 • A powerful Group I 4 2003, an ambitious project becomes reality • 2003 key figures I 6 • Corporate governance I 8 • Crédit Agricole S.A. group Management I 12 • 2003 review of operations I 14 • French retail banking – Regional Banks I 16 • French retail banking – Crédit Lyonnais I 26 • Specialised financial services I 34 • Asset management, insurance and private banking I 44 • Corporate and investment banking I 54 • International retail banking I 64 • Sustainable development I 68 Solidarity and commitment to society Human resources and relations Customer and supplier relations Environmental protection Crédit Agricole S.A. share data • Summary chart of subsidiaries and affiliates I 92 Crédit Agricole S.A. 2003 annual report • Crédit Agricole group I 94 Summary balance sheet and income statement Addresses and management of the Regional Banks Crédit Agricole S.A. A French limited company with a share capital of € 4,420,567,311 Paris Trade and Company Registry No. 784 608 416 AMF Only the French language version of the shelf-registration document has been submitted to the AMF. -

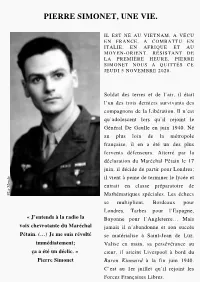

Décès De Pierre Simonet, Elysée

PIERRE SIMONET, UNE VIE. IL EST NÉ AU VIETNAM, A VÉCU EN FRANCE, A COMBATTU EN ITALIE, EN AFRIQUE ET AU MOYEN-ORIENT. RÉSISTANT DE LA PREMIÈRE HEURE, PIERRE SIMONET NOUS A QUITTÉS CE JEUDI 5 NOVEMBRE 2020. Soldat des terres et de l’air, il était l’uN des trois derNiers survivaNts des compagNoNs de la LibératioN. Il N’est qu’adolesceNt lors qu’il rejoiNt le GéNéral De Gaulle eN juiN 1940. Né au plus loiN de la métropole fraNçaise, il eN a été uN des plus ferveNts défeNseurs. Atterré par la déclaratioN du Maréchal PétaiN le 17 juiN, il décide de partir pour LoNdres; e il vieNt à peiNe de termiNer le lycée et d N o eNtrait eN classe préparatoire de M e L Mathématiques spéciales. Les échecs © se multiplieNt, Bordeaux pour LoNdres, Tarbes pour l’EspagNe, « J’eNteNds à la radio la BayoNNe pour l’ANgleterre… Mais voix chevrotaNte du Maréchal jamais il N’abaNdoNNe et soN succès PétaiN. (…) Je me suis révolté se matérialise à SaiNt-JeaN de Luz. immédiatemeNt; Valise eN maiN, sa persévéraNce au ça a été uN déclic. » cœur, il atteiNt Liverpool à bord du Pierre SimoNet BaroN KiNNaird à la fiN juiN 1940. C’est au 1er juillet qu’il rejoiNt les Forces FraNçaises Libres. A défaut d’eNtrer daNs l’aviatioN -il N’a positioNs soNt duremeNt attaquées et alors pas le brevet de pilote- il est affecté que le capitaiNe de l’opératioN a ordre daNs l’Artillerie FFL, alors eN cours de de partir, SimoNet Ne quitte soN poste créatioN. -

Revue De La Fondation De La France Libre N° 43

www.france-libre.net 43 R EVUE DE LA F ONDATION DE LA F RANCE L IBRE -MARS 2012 SommaireSommaire La Vie de la Fondation Le mot du président. 1 Les archives de la France Libre. 1 Troisième Convention générale des participants de la Fondation de la France Libre. 2 Le programme du 70e anniversaire de Bir Hakeim 4 Les 70 ans de Bir Hakeim sur Internet 5 Histoire De Paris-Soir au groupe Cigognes 6 Revue d’information Documents 14 trimestrielle de la Trois archéologues au service de la France Libre 16 Fondation de la France Libre L’engagement de Raymond Aron dans les Forces françaises libres 19 Parution : Mars 2012 Numéro 43 Livres 21 In memoriam 24 Carnet 29 Dans les délégations 30 Chez nos amis 70e anniversaire de la création du SAS 33 Le site de l’ADFL tisse sa « toile » inter-générationnelle 34 La vie au club 35 © « BULLETIN DE LA FONDATION DE LA FRANCE LIBRE ÉDITÉ PAR Abonnement annuel : 15 Euros LA FONDATION DE LA FRANCE LIBRE » Il est interdit de reproduire intégralement ou partiellement la présente publica- N° commission paritaire : 0212 A 056 24 tion - loi du 11 mars 1957 - sans autorisation de l’éditeur. La conception de la N° ISSN : 1630-5078 croix de Lorraine pour la une de couverture est un copyright © CASALIS, Reconnue d’utilité publique (Décret du 16 juin 1994) gracieusement mis à la disposition de la Fondation. RÉDACTION, ADMINISTRATION, PUBLICITÉ : MISE EN PAGE, IMPRESSION, ROUTAGE : 59, rue Vergniaud - 75013 Paris Imprimerie MONTLIGEON - 02 33 85 80 00 Tél.:0153628182-Fax:0153628180 er trimestre 2012 E-mail : [email protected] Dépôt légal 1 DIRECTEUR DE LA PUBLICATION : Général Robert BRESSE VERSEMENTS : CCP Fondation de la France Libre Paris CCP La Source 42495 11 Z RÉDACTEUR EN CHEF : Sylvain CORNIL-FRERROT Prix au N° : 5 Euros CONCEPTION GRAPHIQUE : Bruno RICCI LA VIE DE LA FONDATION Le mot du président année 2012 sera pour nous celle du 70e anniversaire de Bir Hakeim. -

L'hommage De Pierre Simonet

PIERRE SIMONET LES AILES DE LA LIBER ATION Lettre manuscrite de Pierre SIMONET au M-CR Bernard François MICHEL, en 2010. Pierre SIMONET, Compagnon de la Libération, nous a quittés le 5 novembre 2020. Le déroulé de la cérémonie funéraire a dû être adaptée aux conditions sanitaires par la famille de Pierre SIMONET. Michel MAGNALDI représentait la Fondation de la France Libre pour le VAR. Le Médecin en ChefR Bernard François MICHEL, au nom de la Mémoire de la 1re DFL et de la Fondation Charles De GAULLE, a lu un hommage à Pierre SIMONET, rédigée en commun avec Marie-Hélène CHATEL, déléguée Mémoire de la 1ère DFL. Le texte est reproduit ci-dessous*. Bernard François MICHEL qui connaissait personnellement depuis de nombreuses années Pierre SIMONET, était accompagné de Madame Joëlle COLMAY-ROBERT, fille de Compagnon de la Libération, représentant l’Association des Familles de Compagnons de la Libération (AFCL). Ils ont déposé ensembles une gerbe, après s’être recueillis devant la dépouille de Pierre SIMONET. TOULON, le 11 novembre 2020* C’est au nom de la « Mémoire de la Première Division Française Libre (1ère DFL) » et de la « Fondation Charles De GAULLE » que nous nous adressons à vous aujourd’hui. La 1ère DFL vient de perdre un grand homme, un grand français libre. Pierre SIMONET n’a pas hésité à quitter la FRANCE, le 24 juin 1940, et parvenant à embarquer sur le dernier cargo, le BARON KINNAIRD, qui, en rade de SAINT-JEAN-DE-LUZ, rapatriait les troupes polonaises et les résidents britanniques, rejoindre l’ANGLETERRS. Arrivé à LIVERPOOL, il s'engagea dans les Forces Françaises Libres (FFL) en juillet 1940. -

La Voix Du Combattant Mars 2020 VOIX1853 COM 003-004.Qxp MAG VDC 3 COL 24/02/2020 10:09 Page 3

VOIX1853_COM_001.qxp_Base 24/02/2020 10:02 Page 1 LALA VOIXVOIX DUDU mars 2020 N°1853 - COMBATTANTCOMBATTANT Le magazine de l’Union nationale des combattants Commandos de chasse en Algérie Témoignage Opex Vie de l’UNC Mémoire combattante Commandos parachutistes Les photos du conseil Le général Durand, Éditorial en Centrafrique p.18 des départements p.32 soldat oublié p.36 « Formons nos bataillons ! » p. 3 VOIX1853_COM_002.qxp_MAG_VDC_3_COL 20/02/2020 10:58 Page 2 Le coup de cœur de la rédaction © Photos : CNSD Une marraine de marque rigitte Macron, épouse du chef de l’État, en rencontrant des sportifs de accompagnée de Florence Parly, minis‐ l’Armée de Champions prépa‐ Btre des Armées et de Béatrice Abolli‐ rant des échéances internatio‐ vier, préfète de Seine‐et‐Marne, a été nales, olympiques et paralym‐ accueillie, le 14 février, au Centre national des piques ainsi que des jeunes des sports de la Défense (CNSD) à Fontainebleau pôles France du CNSD. Le sport (77) par le commissaire en chef de 1re classe d’élite a été évoqué avec l’en‐ Hervé Piccirillo, commandant le CNSD. gagement des équipes de La première dame a en effet accepté de deve‐ France militaires qui portent nir la marraine de l’équipe de France des bles‐ haut nos couleurs sur les com‐ sés de la Défense et de la Gendarmerie, enga‐ pétitions du Conseil internatio‐ gée aux prochains Invictus Games, en mai nal du sport militaire. Fevrier, directeur technique national et Denis 2020 aux Pays‐Bas. Aux côtés de la ministre des En point d’orgue, Brigitte Macron a échangé Chareyre, conseiller technique. -

Vygon Business Responsibility Issue 2012 C ONTENT of the VYGON CSR REPORT

Vygon Business Responsibility Issue 2012 C ONTENT OF THE VYGON CSR REPORT Background to the Vygon Group ............................................................................................................ 1 Vygon (Sweden) AB .................................................................................................................................. .2 Statement from Mikael Hedström, Managing Director, Vygon Sweden ...................................... ..3 Vygon Sweden first CSR Report ........................................................................................................... ..4 CSR Governance ...................................................................................................................................... ..5 Commitments to External Initiatives ................................................................................................... ..5 Application Level Qualification ............................................................................................................ …6 Vygon Sweden data summery table……………………………………………………………7 Stakeholder Engagement .................................................................................................................. ……8 . Stakeholder Engagement - The Customer………………..…………………...……….9 . Stakeholder Engagement - Vygon……………………………………………………...9 . Stakeholder engagement - Vygon Sweden employees..………………………….…..10 . Materiality…………………………………………………………………………….10 . Responsiveness……………………………………………………………………….11 . Contact with Vygon..…………………………………………………………………11 -

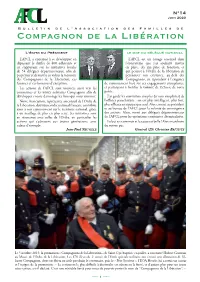

Bulletin AFCL 2020

N°14 Juin 2020 Bulletin de l’Association des Familles de Compagnon de la Libération L’édito du Président le mot du délégué national L’AFCL a continué à se développer en L’AFCL est un rouage essentiel dans dépassant le chiffre de 400 adhérents et l’écosystème que j’ai souhaité mettre en s’appuyant sur les initiatives locales en place, dès ma prise de fonction, et de 54 délégués départementaux, afin de qui permet à l’Ordre de la libération de perpétuer et de mettre en valeur la mémoire pérenniser son existence, au-delà des des Compagnons de la Libération, ces Compagnons, en répondant à l’exigence femmes et ces hommes d’exception. de rayonnement basé sur ces engagements exemplaires, Les actions de l’AFCL sont tournées aussi vers les et participant à fortifier la volonté de Défense de notre communes et les unités militaires Compagnon afin de patrie. développer encore davantage les liens qui nous unissent. J’ai gardé les conviction simples (et non simplistes) de Notre Association, représentée au conseil de l’Ordre de l’officier parachutiste : on est plus intelligent, plus fort, la Libération, deuxième ordre national français, contribue plus efficace en équipe que seul. Alors, merci au président ainsi à son rayonnement sur le territoire national, grâce et au bureau de l’AFCL pour la volonté de convergence à un maillage de plus en plus serré. Ses initiatives sont des actions. Alors, merci aux délégués départementaux en résonance avec celles de l’Ordre, en particulier les de l’AFCL pour les opérations conjointes décentralisées. -

ET LE COMMERCE Limited Distribution

GENERAL AGREEMENT ACCORD GENERAL SUR RESTRICTED ON TARIFFS AND LES TARIFS DOUANIERS 21COM.TD/W/87January 1969 TRADE ET LE COMMERCE Limited Distribution Comitécommercedu et du développement ThirteenthCommitteeSession onTradeandDevelopment Treizième session Chairman: LISTOFPresident:REPRESENTATIVESH.E. -Mr.LISTET. SWAMINATHANDESDREPRESENTANTS ARGENTINA Representantes Sr. Fernando G. Lerena Ministro Consejero económic y comercial, Misión Permanente ante los Organismos Internacionales en Ginebra Sr. Julio César Raimondi Consejero económico y comercial, Misión Permanente ante los Organismos Internacionales en Ginebra AUSTRALIA Mr. G.J. Hall Commercial Counsellor, Permanent Mission to the Office of the United Nations at Geneva AUSTRIA Representatives Mr. Gerhard Waas Secretary, Federal Ministry of Trade and Industry Mr. Franz Bock Secretary, Permanent Mission to the Office of the United Nations at Geneva Secretaryof Committee: Mr. D. Peart, Villa Le Bocage, Tel. Ext. 2097. ConferenceOfficer: Miss S. Niklaus, Villa Le Bocage, Tel. Ext. 4411, COM.TD/W/87 Page 2 BELGIQUE Représentants M. Guy Stuyck Representant permanent auprès du GATT M. S. Taloen Conseiller adjoint, Ministère des Affaires économiques BRAZIL Mr. Braulino B. Barbosa Minister Counsellor, Permanent Mission to the Office of the United Nations at Geneva CAMEROUN (liste non reçue) CANADA Representative Mr. F.R. Petrie Counsellor (economic affairs), Permanent Mission to the Office of the United Nations at Geneva REPUBLIQUE CENTRAFRICAINE (liste non reçue) CEYLON Representative Mr. L.J. Mariadasan Trade Commissioner, Office of the High Commissioner in the United Kingdom CHILE Representantes Sr. Carlos Besa Representante Permanente ante el GATT Sr. Fernando Cisternas Primer Secretario de Embajada ante el GATT Sr. Mario Cademàtori Tercer Secretario, Delegación Permanente ante el GATT COM.TD/W/87 Page 3 COTE D'IVOIRE Représentants S.E. -

Press-Kit-CDT-Dordogne-Perigord

Superb heritage Family fun Gastronomic delights Sports & outdoor activities Traditional skills New experiences Exciting adventures Unique Dordogne PRESS KIT 2017 02PRESS KIT 2017 MAP OF THE DORDOGNE LIMOGES BRIVE BORDEAUX TOULOUSE GETTING TO THE DORDOGNE BY TRAIN: BY CAR: • TGV stations in Angoulême, Bordeaux and Libourne • Périgueux-Paris - 550km • TER stations in Périgueux, Bergerac, Sarlat and elsewhere. • Périgueux-Lyon on the A89 - 400km BY PLANE • Périgueux-Bordeaux on the A89 - 120km • Périgueux –Paris with Twin Jet • Bergerac : 15 international flights 03PRESS KIT 2017 CONTENTS 6 > 9 10 > 12 A JOURNEY UNIQUE CULTURAL THROUGH EXPERIENCES PREHISTORY 13 > 15 16 STUNNING TOWNS SPORTS EVENTS IN 2017 17 > 18 19 20 > 21 BY BIKE OR ON FOOT WHAT’S NEW IN FAMILY DORDOGNE OUR GARDENS? 22 > 27 28 > 31 GASTRONOMIC TRADITIONAL DELIGHTS SKILLS 32 > 33 34 SUSTAINABLE TOURISM FOR TOURISM DISABLED VISITORS PRESS 35 > 37 38 > 39 CONTACTS: ACCOMMODATION, FESTIVE AND Micheline Morissonneau / WHAT’S NEW? CULTURAL PERIGORD Carine Gutierrez [email protected] Tel: +33 (0)5 53 35 50 05 www.dordogne-perigord-tourisme.fr 04PRESS KIT 2017 GENERAL INTRODUCTION FACTS AND FIGURES Facts and figures: Tourism in numbers: 191 sites and monuments open to visitors • Region: Nouvelle Aquitaine 15 UNESCO World Heritage-listed prehistoric sites 9 prehistoric deposits • Prefecture: Périgueux 9 painted caves and shelters • Sub-prefectures: Bergerac, Sarlat, Nontron 6 troglodyte sites and villages 5 caves and chasms with crystallisations Surface area: 49 castles 9,060km², -

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade Accord

GENERAL AGREEMENT ACCORD GENERAL SURRESTRICTED ON TARIFFS AND LES TARIFS DOUANIERS 3COM.TD/W/10June 19692 TRADE ET LE COMMERCE Limited Distribution Committee on Trade and Development Comité du commerce et du développement Fourteenth Session Quatorzieme session LIST OF REPRESENTATIVES - LISTE DES REPRESENTANTS Chairman: President: H.E. Mr. T. SWAMINATHAN (India) ARGENTINA Representante Sr. Julio César Raimondi Consejero económico y commercial, Misión Permanente ante los Organismos Internacionales en Ginebra AUSTRALIA Representative Mr. G.J. Hall Commercial Counsellor, Permanent. Mission to the Office of the United Nations at Geneva AUSTRIA Representative Mr. Franz Bock Secretary, Permanent Mission to the Office of the United Nations at Geneva BELGIQUE Représentants M. Guy Stuyck Représentant permanent auprès du GATT M. S. Taloen Conseiller adjoint, Ministère des Affeires économiques Secretary of Committee: Mr. D. Peart, Villa Le Bocage, Tel. Ext. 2097. Conference Officer: Miss S. Niklaus, Villa Le Bocage, Tel. Ext. 4411. COM. TD/W/102 Page 2 BRAZIL Representatives Mr. Braulino B. Barbosa Minister Counsellor, Permanent Mission to the Office of the United Nations at Geneva Mr. Mauro Couto First Secretary of Embassy, Permanent Mission to the Office of the United Nations at Geneva CAMEROUN (liste non reçue) CANADA Representative Mr. F.R. Petrie Counsellor (Economic affairs), Permanent Mission to the Office of the United Nations at Geneva REPUBLIQUE CENTRAFPICAINE Représentant S.E. M. R... Guerillot Ambassadeur, Ambassade à Bruxelles CEYLON Representative Mr. L.J. Mariadasan Trade Commissioner, Office of the High Commissioner in the United Kingdom CHILE Representantes Sr. Carlos Besa Representante Permanente ante el GATT Sr. Mario Cademártori Tercer Secretario, Delegación Permanente ante el GATT Sta. -

Les COMPAGNONS DE La Libération S’Engager, Résister Pour La Liberté

COllèGE FICHES PÉDAGOGIQUES D’ACCOMPAGNEMENT lES COMPAGNONS DE lA lIbÉrATION S’ENGAGEr, rÉSISTEr POUr lA lIbErTÉ MINISTÈRE DE L’ÉDUCATION NATIONALE, MINISTÈRE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR, DE LA RECHERCHE ET DE L’INNOVATION Ces fiches ont été rédigées par Jean-Charles Buttier, enseignant de collège et chargé de cours à l’Université de Genève 1 COllèGE FICHES PÉDAGOGIQUES D’ACCOMPAGNEMENT lES COMPAGNONS DE lA lIbÉrATION S’ENGAGEr, rÉSISTEr POUr lA lIbErTÉ Fiche enseignant-e N°1 LA CRÉATION DE L’orDRE DE LA LIBÉRATION PAR LE GÉNÉRAL DE GAULLE (1940) ............................... 2 Fiche enseignant-e N°2 L’ORDRE DE LA LIBÉRATION AUJOURd’hUI : ENTRE HISTOIRE ET MÉMOIRE ......................................................... 8 Fiche enseignant-e N°3 FORMES ET LIEUX DE LA RÉSISTANCE INTÉRIEURE ET EXTÉRIEURE ............................................................................. 14 Fiche enseignant-e N°4 LE DILEMME DE L’ENGAGEMENT ................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 21 Fiche enseignant-e N°5 LES FEMMES DANS L’orDRE DE LA LIBÉRATION .......................................................................................................................................................... 26 Fiche enseignant-e N°6 UNE UNITÉ MILITAIRE DÉCORÉE : LE SOUS-MARIN RUBIS ....................................................................................................................