Inspection Copy Inspection Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EXPERT REVIEW DRAFT IPCC SREX Chapter 9 Do Not Cite, Quote, Or

EXPERT REVIEW DRAFT IPCC SREX Chapter 9 1 Chapter 9. Case Studies 2 3 Coordinating Lead Authors 4 Gordon McBean (Canada), Virginia Murray (UK), Mihir Bhatt (India) 5 6 Lead Authors 7 Sergey Borshch (Russian Federation), Tae Sung Cheong (South Korea), Wadid Fawzy Erian (Egypt), Silvia Llosa 8 (Peru), Farrokh Nadim (Norway), Arona Ngari (Cook Islands), Mario Nunez (Argentina), Ravsal Oyun (Mongolia), 9 Avelino G. Suarez (Cuba) 10 11 Note: Also see authors and contributing authors for each case study. 12 13 14 Contents 15 16 9.1. Introduction 17 9.1.1. Description of Case Studies Approach in General 18 9.1.2. Case Study Analyses: Lessons Identified and Learned – Good and Bad Practices 19 20 9.2. Methodological Approach 21 9.2.1. Case Studies 22 9.2.2. Literature: Papers, Reports, Grey Literature 23 9.2.3. Relationship between Extreme Climate-Related Events and Climate Change 24 9.2.4. Scale 25 26 9.3. Case Studies 27 9.3.1. Extreme Events 28 – Case Study 9.1. Tropical Cyclones 29 – Case Study 9.2. Urban Heat Waves, Vulnerability and Resilience 30 – Case Study 9.3. Drought and Famine in Ethiopia in the Years 1999-2000 31 – Case Study 9.4. Sand and Dust Storms 32 – Case Study 9.5. Floods 33 – Case Study 9.6. Drought, Heat Wave, and Black Saturday Bushfires in Victoria 34 – Case Study 9.7. Dzud of 2009-2010 in Mongolia 35 – Case Study 9.8. Disastrous Epidemic Disease: The Case of Cholera 36 9.3.2. Vulnerable Regions and Populations 37 – Case Study 9.9. -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO Diploma Thesis

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Declaration I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. I agree with the placing of this thesis in the library of the Faculty of Education at the Masaryk University and with the access for academic purposes. Brno, 30th March 2018 …………………………………………. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. for his kind help and constant guidance throughout my work. Bc. Lukáš Opavský OPAVSKÝ, Lukáš. Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis; Diploma Thesis. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, English Language and Literature Department, 2018. XX p. Supervisor: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Annotation The purpose of this thesis is an analysis of a corpus comprising of opening sentences of articles collected from the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia. Four different quality categories from Wikipedia were chosen, from the total amount of eight, to ensure gathering of a representative sample, for each category there are fifty sentences, the total amount of the sentences altogether is, therefore, two hundred. The sentences will be analysed according to the Firabsian theory of functional sentence perspective in order to discriminate differences both between the quality categories and also within the categories. -

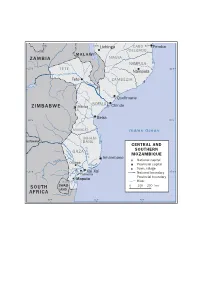

The Effectiveness of Foreign Military Assets in Natural Disaster Response

30°E 35°E Lichinga CABO 40°E Pemba DELGADO M A L A W I ZAMBIA NIASSA NAMPULA 15°S TETE 15°S Nampula Tete ZAMBÉZIA Zambezi Quelimane SOFALA ZIMBABWE Manica Chinde Beira 20°S 20°S MANICA Indian Ocean INHAM- BOTSWANA BANE CENTRAL AND Chang Indian Ocean Limpopo G A Z A SOUTHERN ane MOZAMBIQUE Inhambane National capital Olifants Chókwè Provincial capital Incomáti Town, village 25°S Xai Xai 25°S Palmeira National boundary Maputo Provincial boundary Umbeluzi River SOUTH SWAZI- 0 100 200 km AFRICA LAND 30°E 35°E 40°E Annex A Case study: Floods and cyclones in Mozambique, 2000 In January and February 2000 prolonged heavy rains and the cyclones Connie and Eline caused catastrophic flooding in Mozambique’s Gaza, Inhambane, Manica, Maputo and Sofala provinces. An estimated 2 million people were affected, 544 000 were displaced and 699 were killed. The World Bank estimated the economic damage caused by the floods and cyclones to be approximately 20 per cent of the country’s gross national product.1 Mozambique’s recently created disaster management structure was quickly overwhelmed by the scale of the humanitarian crisis. A major international assistance effort included foreign military assets from 11 countries. These countries eventually allowed their assets to be under United Nations coordination to an unprecedented degree. It was the first time that the concept of a Joint Logistics Operation Centre to manage and coordinate air assets was applied in a natural disaster response. Another similar bout of flooding in the country in 2007 provides a useful comparison of the responses and some indication of how, and how far, the lessons of 2000 have been applied. -

Independent Evaluation of Expenditure of DEC Mozambique Floods Appeal Funds March to December 2000 Volume One: Main Report

Independent Evaluation of Expenditure of DEC Mozambique Floods Appeal Funds March to December 2000 Volume One: Main Report This evaluation is published in two volumes, of which this is the first. Volume one contains the main findings of the evaluation including the executive summary. Volume two contains the appendices including the detailed beneficiary study and the summaries of the activities of the DEC agencies. Each agency summary looks at key issues relating to the performance of the agencies as well as presenting general data about their programme. The executive summary has also been published as a stand- alone document. Independent evaluation conducted by Valid International and ANSA Valid, 3 Kames Close Oxford, OX4 3LD UK Tel: +44 1865 395810 Email: [email protected] http://www.validinternational.org © 2001 Disasters Emergency Committee 52 Great Portland Street London, W1W 7HU Tel: +44 20 7580 6550 Fax: +44 20 7580 2854 Website: http://www.dec.org.uk Further details about this and other DEC evaluations can be found at the DEC website. Evaluation of DEC Mozambique Floods Appeal Page 2 Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge the more than four hundred people who gave their time to answer the evaluation team’s questions. Special thanks are due for the full and generous assistance received from the DEC agencies in Mozambique during the evaluation. Not only did the evaluation team receive full and detailed answers to their many questions, but also received the full assistance of the DEC agencies in visiting many project sites throughout the county. Evaluation Data Sheet Title: Independent Evaluation of Expenditure of DEC Mozambique Floods Appeal Funds – March to December 2000 Client: Disasters Emergency Committee http://www.dec.org.uk Date: 23 July 2001 Total pages: 94. -

The Climate of Poverty: Facts, Fears and Hope

The climate of poverty: facts, fears and hope A Christian Aid report May 2006 Contents Introduction 1 Climate change – destroying development 4 Empowering the poor 13 Kenya: drought and conflict 28 Bangladesh: erosion and flood 32 Recommendations 38 Endnotes 42 Front cover: Cleaning solar panels on the roof of the business centre in Wawan Rafi, Nigeria. With solar electricity the centre’s shops now can stay open until midnight. The Jigawa Alternate Energy Fund started the solar project in 2001 Front cover photo: Christian Aid/Sam Faulkner/NB Pictures The climate of poverty Introduction If 2005 was the year of Make Poverty History, then 2006 is turning into the year of Climate Change. Scarcely a week goes by without a new set of statistics being released or leaked, showing the accelerating process of global warming – and prompting ever more dire predictions about the future of the planet. It may seem, then, that the news agenda has moved on – away from issues of aid, debt and trade, and how they affect the world’s poorest people. Christian Aid, however, believes that poverty and climate change are inextricably linked. As this report graphically illustrates, it is the poor of the world who are already suffering disproportionately from the effects of global warming. The report also definitively shows that poor people in the world’s most vulnerable communities will bear the brunt of the forecast ‘future shock’. The potential ravages of climate change are so severe that they could nullify efforts to secure meaningful and sustainable development in poor countries. At worst, they could send the real progress that has already been achieved spinning into reverse. -

Mozambique and Other Recent Flood Disasters: Comparing the U.S

Order Code RS20518 Updated April 17, 2000 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Mozambique and Other Recent Flood Disasters: Comparing the U.S. and International Responses Lois McHugh Foreign Affairs Analyst Foreign Affairs, Defense and Trade Summary Some have criticized the U.S. response to the recent floods in southern Africa. Their concern has been that the U.S. response has been too little and too late in comparison with disasters in other parts of the world. U.S. spokesmen argue that their response has been appropriate and timely with contributions to Mozambique of over $32 million and additional contributions to the region of over $40 million. The U.S. government has responded to eight flood disasters thus far in FY2000 in addition to the current flooding in southern Africa. This report and the table on p. 6 compare the U.S. and international responses to each. The report will be updated. Current Disaster in Mozambique and Southern Africa South Africa, Mozambique, Swaziland, Botswana, Madagascar, and Zimbabwe experienced their worst flooding in decades during January and February 2000. In addition, Cyclone Connie brought rains in the first week of February, Cyclone Leon-Eline crossed the region between February 17 and 23, and Tropical Depression Gloria a few days later added significant rainfall. Continuing release of excess water to protect dams in the region also contributed to the flooding in Mozambique. About 2 million people have been affected by flooding in southern Africa and the regional death toll is estimated to be 1,000. Mozambique declared a disaster on February 7, Botswana on February 16, South Africa on February 17, and Zimbabwe on February 29. -

Developing a Flood Monitoring System from Remotely Sensed Data for the Limpopo Basin

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/3205331 Developing a Flood Monitoring System From Remotely Sensed Data for the Limpopo Basin Article in IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing · July 2007 DOI: 10.1109/TGRS.2006.883147 · Source: IEEE Xplore CITATIONS READS 43 192 5 authors, including: Kwabena Asante G. A. Artan University of Essex Igad Climate Prediction and Applications Ce… 27 PUBLICATIONS 326 CITATIONS 29 PUBLICATIONS 381 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by G. A. Artan on 03 December 2013. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. All in-text references underlined in blue are added to the original document and are linked to publications on ResearchGate, letting you access and read them immediately. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON GEOSCIENCE AND REMOTE SENSING, VOL. 45, NO. 6, JUNE 2007 1709 Developing a Flood Monitoring System From Remotely Sensed Data for the Limpopo Basin Kwabena O. Asante, Rodrigues D. Macuacua, Guleid A. Artan, Ronald W. Lietzow, and James P. Verdin Abstract—This paper describes the application of remotely quantities of precipitation that conspired with the wet soils and sensed precipitation to the monitoring of floods in a region that high reservoir levels from antecedent events to produce the regularly experiences extreme precipitation and flood events, flood of record in the lower reaches of the Limpopo River basin often associated with cyclonic systems. Precipitation data, which -

Flood Management in Mozambique

Flood Management in Mozambique Aerial picture showing the impact of cyclone Jokwe when Zambezi river burst its banks at Vilankulos, Mozambique. Photo by DFID/UK This case study: - Highlights the key role of Mozambique’s National Institute of Meteorology in Disaster Risk Management and the capabilities of the early warning system during the 2000 flood event in Mozambique. - Shows importance of the National Institute of Meteorology strengthening skill through its relations with Harare - Climate Services Centre consensus climate guidance and the need to strengthen the national early warning system. - Exhibits elements of the WMO Strategy on Service Delivery and the end-to-end generation of climate information ensuring disseminated information is usable and reaches vulnerable communities with user feedback for product improvement. - The role of the National Institute of Meteorology as a team player in a multi-disciplinary team effort to manage a climate extreme event in the national and regional context. - Highlights national ownership and commitment to strengthen the early warning system to manage future more frequent and severe floods effectively Background Mozambique’s long-term challenge is to learn to live with floods and drought. Mozambique is one of the poorest countries in the world, with more than 50% of its 19.7 million people living in extreme poverty. Development has been compromised in recent years by these hydrometeorological disasters leading to economic growth rates decline from 12% before the 2000 floods to 7% after the floods. Mozambique’s high incidence of flooding is explained by two factors. First is the tropical cyclones that form in the south-western Indian Ocean and sweep towards the country’s coast. -

EWS Economics

Background Paper on Assessment of the Economics of Early Warning Systems for Disaster Risk Reduction1 Submitted to The World Bank Group Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) for Contract 7148513 Submitted by A.R. Subbiah Lolita Bildan Ramraj Narasimhan Regional Integrated Multi-Hazard Early Warning System 1 This paper was commissioned by the Joint World Bank - UN Project on the Economics of Disaster Risk Reduction. We are grateful to Apurva Sanghi, Saroj Jha, Thomas Teisberg, Rodney Weiher, and seminar participants at the World Bank for valuable comments, suggestions, and advice. Funding of this work by the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery is gratefully acknowledged. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the author(s). Facilitated by the Asian Disaster Preparedness Center 1 December 2008 Background Paper on Assessment of the Economics of Early Warning Systems for Disaster Risk Reduction Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................. v 1. Introduction and Methodology ................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Methodology for Quantification of Benefits of EWS ................................................................. 2 2. Case -

Annual Summary of Global Tropical Cyclone Season

ANNUAL SUMMARY OF GLOBAL TROPICAL CYCLONE SEASON 2000 WMO/TD-No. 1082 Report No. TCP - 46 SECRETARIAT OF THE WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANIZATION - GENEVA - SWITZERLAND 2000 Edition CONTENTS Page PART A Introduction 1 Monitoring, forecasting and warning of tropical cyclones 3 Tropical cyclone RSMCs 6 RSMC La Réunion - Tropical Cyclone Centre RSMC Miami - Hurricane Center/USA National Hurricane Center RSMC Nadi - Tropical Cyclone Centre RSMC - tropical cyclones New Delhi RSMC Tokyo - Typhoon Center Tropical cyclone warning centres with regional responsibility 10 PART B ANNUAL TROPICAL CYCLONE SUMMARIES (YEAR 2000) I. RSMC La Réunion - Tropical Cyclone Centre II. RSMC Miami - Hurricane Center/USA National Hurricane Center III. RSMC Nadi - Tropical Cyclone Centre, TCWC - Brisbane, TCWC - Wellington IV. RSMC - tropical cyclones New Delhi V. RSMC Tokyo - Typhoon Center VI. CPHC - Honolulu, RSMC Miami - Hurricane Center VII. TCWC - Darwin, TCWC - Perth, (TCWC - Brisbane) 2000 Edition INTRODUCTION About 80 tropical cyclones form annually over warm tropical oceans. When they develop and attain an intensity with surface wind speed exceeding 118 km/h, they are called hurricanes in the western hemisphere, typhoons in the western North Pacific region and severe tropical cyclones, tropical cyclones or similar names in other regions. Such tropical cyclones are among the most devastating of all natural hazards. Their potential for wrecking havoc caused by their violent winds, torrential rainfall and associated storm surges, floods, tornadoes and mud slides is exacerbated by the length and width of the areas they affect, their severity, frequency of occurrence and the vulnerability of the impacted areas. Every year several tropical cyclones cause sudden-onset disasters of varying harshness, with loss of life, human suffering, destruction of property, severe disruption of normal activities and set-back to social and economic advances. -

Unprecedented 2Nd Intense Cyclone Hits Mozambique

MOZAMBIQUE News reports & clippings 454 26 April 2019 Editor: Joseph Hanlon ( [email protected]) To subscribe: tinyurl.com/sub-moz To unsubscribe: tinyurl.com/unsub-moz This newsletter can be cited as "Mozambique News Reports & Clippings" Articles may be freely reprinted but please cite the source. Previous newsletters and other Mozambique material are posted on bit.ly/mozamb Downloadable books: http://bit.ly/Hanlon-books Election data: http://bit.ly/MozElData __________________________________________________________________________ Unprecedented 2nd intense cyclone hits Mozambique Cyclone Kenneth, the strongest ever to hit Mozambique, made landfall yesterday (25 April) evening on the coast of Cabo Delgado between Macomia and Mocimboa da Praia, causing serious damage to those to districts and to the offshore islands in Ibo district. There was less damage in Palma, on the northern edge of the cyclone and with the main gas projects, and Pemba, on the southern edge. This is the first time Mozambique has had two such serious cyclones, in a recorded history going back 50 years. Cyclone Idai made landfall at Beira on 15 March with winds up to 180 km/h while Kenneth had winds of up to 210 km/h. On the widely used Saffir-Simpson scale, Cyclone Kenneth is the first ever category 4 cyclone, and Idai was category 3. The only comparable year was 2000, in which there was massive flooding in the Limpopo River valley and flooding on the Pungue and Buzi rivers similar to this year. In that year there were two cyclones, Eline was category 3 and Huddah was category 1. In additional there were remnants of two other cyclones, Connie and Gloria, which added to the flooding. -

The Role of Local Institutions in Reducing Vulnerability to Recurrent Natural Disasters and in Sustainable Livelihoods Development

United Nations Food Deutsche Gesellschaft and Agricultural Organisation für Technische Zusammenarbeit Disaster Mitigation for Sustainable Liv e lihoods P rogram m e (DiM P) THE ROLE OF LOCAL INSTITUTIONS IN REDUCING VULNERABILITY TO RECURRENT NATURAL DISASTERS AND IN SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS DEVELOPMENT Case study Assessing the Role of Local Institutions in Reducing the Vulnerability of At-Risk Communities in Búzi, Central Mozambique Zef an ias Matsimbe Disaster Mitigation for Sustainable Livelihoods Programme (DiMP) Un iversity of Cape Town October 2003 Co-financed by the Rural Institutions and Participation Service of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) The designations employed an d t h e presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not imply any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO. 2 M ap of Mozambique showing the study are a 3 Acknowledgements The Disaster Mitigation for Sustainable Livelihoods Programme at the University of Cape Tow n (DiMP) w ould like to express its appreciation to a number of key people and organisations who generously gave of their time and support in the course of this research. We are grateful to all those who set aside time from their busy schedules to participate in interviews and to provide information relevant to Assessing the Role of Local Institutions in Reducing the Vulnerability of At-Risk Communities in Búzi, Central Mozambique.