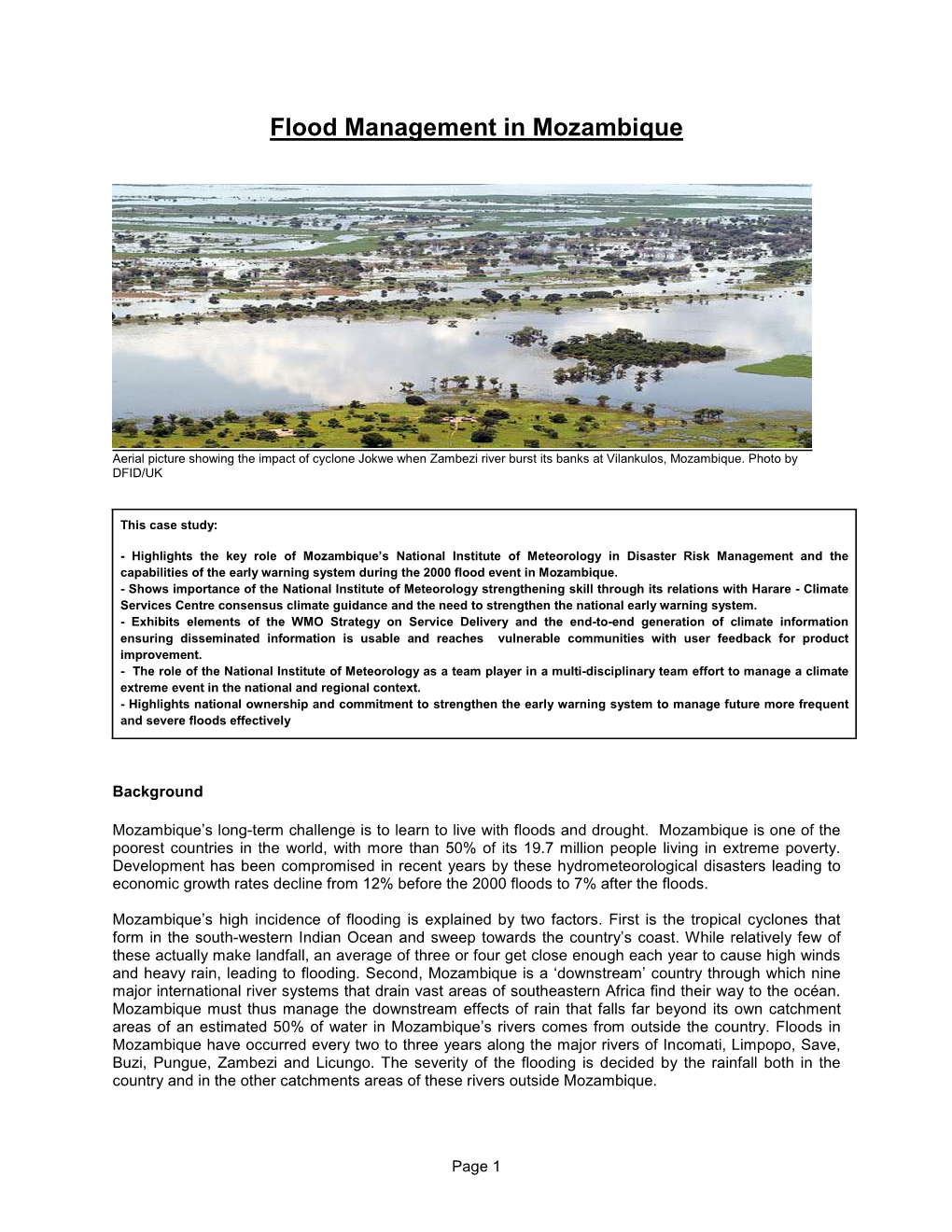

Flood Management in Mozambique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disasters, Climate Change and Human Mobility in Southern Africa: Consultation on the Draft Protection Agenda

DISASTERS, CLIMATE CHANGE AND HUMAN MOBILITY IN SOUTHERN AFRICA: CONSULTATION ON THE DRAFT PROTECTION AGENDA BACKGROUND PAPER South Africa Regional Consultation in cooperation with the Development and Rule of Law Programme (DROP) at Stellenbosch University Stellenbosch, South Africa, 4-5 June 2015 DISASTERS CLIMATE CHANGE AND DISPLACEMENT EVIDENCE FOR ACTION NORWEGIAN NRC REFUGEE COUNCIL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Southern Africa Consultation will be hosted by the Development and Rule of Law Programme (DROP) at Stellenbosch University in South Africa and co-organized in partnership with the Nansen Initiative Secretariat and the Norwegian Refugee Council. The project is funded by the European Union with the support of Norway and Switzerland Federal Department of Foreign Aairs FDFA CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................6 1.1 Background to the Nansen Initiative Southern Africa Consultation ...............................................................................7 1.2 Objectives of the Southern Africa Consultation ............................................................................................................7 2. OVERVIEW OF DISASTERS AND HUMAN MOBILITY IN SOUTHERN AFRICA ..............................................................9 2.1 Natural Hazards and Climate Change in Southern Africa ............................................................................................10 2.2 Challenge -

Observation and a Numerical Study of Gravity Waves During Tropical Cyclone Ivan (2008)

Open Access Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 641–658, 2014 Atmospheric www.atmos-chem-phys.net/14/641/2014/ doi:10.5194/acp-14-641-2014 Chemistry © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. and Physics Observation and a numerical study of gravity waves during tropical cyclone Ivan (2008) F. Chane Ming1, C. Ibrahim1, C. Barthe1, S. Jolivet2, P. Keckhut3, Y.-A. Liou4, and Y. Kuleshov5,6 1Université de la Réunion, Laboratoire de l’Atmosphère et des Cyclones, UMR8105, CNRS-Météo France-Université, La Réunion, France 2Singapore Delft Water Alliance, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore 3Laboratoire Atmosphères, Milieux, Observations Spatiales, UMR8190, Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace, Université Versailles-Saint Quentin, Guyancourt, France 4Center for Space and Remote Sensing Research, National Central University, Chung-Li 3200, Taiwan 5National Climate Centre, Bureau of Meteorology, Melbourne, Australia 6School of Mathematical and Geospatial Sciences, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Melbourne, Australia Correspondence to: F. Chane Ming ([email protected]) Received: 3 December 2012 – Published in Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss.: 24 April 2013 Revised: 21 November 2013 – Accepted: 2 December 2013 – Published: 22 January 2014 Abstract. Gravity waves (GWs) with horizontal wavelengths ber 1 vortex Rossby wave is suggested as a source of domi- of 32–2000 km are investigated during tropical cyclone (TC) nant inertia GW with horizontal wavelengths of 400–800 km, Ivan (2008) in the southwest Indian Ocean in the upper tropo- while shorter scale modes (100–200 km) located at northeast sphere (UT) and the lower stratosphere (LS) using observa- and southeast of the TC could be attributed to strong local- tional data sets, radiosonde and GPS radio occultation data, ized convection in spiral bands resulting from wave number 2 ECMWF analyses and simulations of the French numerical vortex Rossby waves. -

Mozambique Fieldwork Report

Strategic Research into National and Local Capacity Building for DRM Mozambique Fieldwork Report Roger Few, Zoë Scott, Kelly Wooster, Mireille Flores Avila, Marcela Tarazona, Antonio Queface and Alberto Mavume. June 2015 Mozambique Fieldwork Report Acknowledgements The OPM Research Team would like to express sincere thanks to Roberto White from GFDRR Mozambique, Joao Ribeiro from INGC and Wild do Rosário from UN-Habitat for sharing their time and resources. We would also like to thank Joczabet Guerrero and Konstanze Kamojer for their invaluable advice and guidance in relation to the GIZ PRO-GRC project. Finally, we would like to thank all those interviewees and workshop attendees who freely gave their time, expert opinion and enthusiasm, and to Antonio Beleza who assisted the team during the fieldwork. This assessment is being carried out by Oxford Policy Management and the University of East Anglia. The Project Manager is Zoë Scott and the Research Director is Roger Few. For further information contact [email protected] Oxford Policy Management Limited 6 St Aldates Courtyard Tel +44 (0) 1865 207 300 38 St Aldates Fax +44 (0) 1865 207 301 Oxford OX1 1BN Email [email protected] Registered in England: 3122495 United Kingdom Website www.opml.co.uk © Oxford Policy Management i Mozambique Fieldwork Report Table of Contents Acknowledgements i List of Boxes and Tables 3 List of Abbreviations 4 1 Introduction and methodology 7 1.1 Introduction to the research 7 1.2 Methodology 8 1.2.1 Data collection tools 9 1.2.2 Case study procedure 10 1.2.3 -

Ecological Changes in the Zambezi River Basin This Book Is a Product of the CODESRIA Comparative Research Network

Ecological Changes in the Zambezi River Basin This book is a product of the CODESRIA Comparative Research Network. Ecological Changes in the Zambezi River Basin Edited by Mzime Ndebele-Murisa Ismael Aaron Kimirei Chipo Plaxedes Mubaya Taurai Bere Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa DAKAR © CODESRIA 2020 Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa Avenue Cheikh Anta Diop, Angle Canal IV BP 3304 Dakar, 18524, Senegal Website: www.codesria.org ISBN: 978-2-86978-713-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without prior permission from CODESRIA. Typesetting: CODESRIA Graphics and Cover Design: Masumbuko Semba Distributed in Africa by CODESRIA Distributed elsewhere by African Books Collective, Oxford, UK Website: www.africanbookscollective.com The Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) is an independent organisation whose principal objectives are to facilitate research, promote research-based publishing and create multiple forums for critical thinking and exchange of views among African researchers. All these are aimed at reducing the fragmentation of research in the continent through the creation of thematic research networks that cut across linguistic and regional boundaries. CODESRIA publishes Africa Development, the longest standing Africa based social science journal; Afrika Zamani, a journal of history; the African Sociological Review; Africa Review of Books and the Journal of Higher Education in Africa. The Council also co- publishes Identity, Culture and Politics: An Afro-Asian Dialogue; and the Afro-Arab Selections for Social Sciences. -

Daily Sun Article

South African Weather Service Watching the Weather to Protect Life and Property Strong winds and other kinds of rough weather can destroy WHOWHO WE WE ARE ARE houses and lives . THE South African Weather Service is the advanced equipment that aids us in the national provider of weather and climate-re- monitoring and prediction of weather pat- lated information. terns and the collection of climatic-related The past 10 years has seen an increase in information. weather-related natural disasters that have Our improved national weather observa- affected the lives of local communities. tion network has resulted in more accurate The deaths, injuries and damage to prop- weather and climate information, that helps erty caused have hampered sustainable de- us to provide bad weather early warning sys- velopment in both urban and rural commu- tems to the Republic of South Africa. nities, and we play an important role in The South African Weather Service is at helping the South African government to the forefront of providing weather and cli- lessen the effects of weather-related natural mate information in South Africa and we are disasters. confident that the years ahead will see even As an organisation, we are committed to more measures being developed to help pro- reducing the impact of these disasters by in- tect the South African public and keep vesting in the latest and most technologically weather related damage to a minimum. CELEBRATE WORLD METEOROLOGICAL DAY EACH year, on 23 March, the World Meteoro- a specialised agency of the United Nations. resulting distribution of water resources. community to see that that important weather logical Organisation (WMO) – a United Nations The theme for World Meteorological Day South Africa is represented at WMO by the and climate information is available and accessi- organisationwith189members–andtheworld- 2013 is “Watching the Weather to Protect Life CEO of the South African Weather Service ble for global programmes. -

Université D Faculté Des Lettres Départemen

UNIVERSITÉ D’ANTANANARIVO FACULTÉ DES LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUMAINES DÉPARTEMENT DE GÉOGRAPHIE Filière Spécialisée en Environnement et Aménagement du Territoire (F.S.E.A.T) MÉMOIRE POUR L’OBTENTION DU DIPLÔME DE MAITRISE « VULNERABILITE DE LA VILLE COTIERE FACE AUX CYCLONES : CAS DE LA COMMUNE URBAINE D’ANTALAHA REGION SAVA » Présenté par : BE MELSON Evrald Angelo Sous la direction de : Madame Simone RATSIVALAKA, Professeur Titulaire au Département de Géographie Date de soutenance : 1O Octobre 2014 Octobre 2014 UNIVERSITÉ D’ANTANANARIVO FACULTÉ DES LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUMAINES DÉPARTEMENT DE GÉOGRAPHIE Filière Spécialisée en Environnement et Aménagement du Territoire (F.S.E.A.T) MÉMOIRE POUR L’OBTENTION DU DIPLÔME DE MAITRISE « VULNERABILITE DE LA VILLE COTIERE FACE AUX CYCLONES : CAS DE LA COMMUNE URBAINE D’ANTALAHA REGION SAVA » Présenté par : BE MELSON Evrald Angelo Président du jury : James RAVALISON, Professeur Rapporteur : Simone RATSIVALAKA, Professeur Titulaire Juge : Mparany ANDRIAMIHAMINA, Maitre de conférences Octobre 2014 REMERCIEMENTS Ce mémoire de Maitrise n’aurait pas été ce qu’il est aujourd’hui, sans le concours de plusieurs personnes, à qui nous aimerons témoigner notre plus profonde reconnaissance. Tout d’abord, nous remercions de tout profond de notre cœur le Dieu Tout Puissant de nous avoir donné encore la vie et l’opportunité d’avoir pu mener à terme ce travail de recherche. Aussi, Monsieur James RAVALISON, Professeur pour avoir accepté de présider notre soutenance ; Monsieur Mparany ANDRIAMIHAMINA, Maître de conférences pour avoir accepté de juger notre soutenance ; Madame Simone RATSIVALAKA, notre Directeur de mémoire pour sa constante dévotion à notre travail malgré ses multiples occupations. -

Geospatial Analysis of Rain Fields and Associated Environmental Conditions for Cyclones Eline and Hudah

Article Geospatial Analysis of Rain Fields and Associated Environmental Conditions for Cyclones Eline and Hudah Corene J. Matyas and Sarah VanSchoick * Department of Geography, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA; matyas@ufl.edu * Correspondence: sm.vanschoick@ufl.edu; Tel.: +1-3523-920-494 Abstract: Tropical cyclones (TCs) that landfall over Madagascar and Mozambique can cause flooding that endangers lives. To better understand how environmental conditions affect the rain fields of these TCs, this study utilized spatial metrics to analyze two storms taking similar paths two months apart. Using a geographic information system, rain rates of 1 mm/h were extracted from a satellite- based dataset and contoured to define the rain field edge. Average extent of rainfall was measured for each quadrant and asymmetry was calculated along with rain field area, dispersion, closure, and solidity. Environmental conditions and storm intensity were analyzed every six hours. Results indicate that although both TCs intensified prior to first interaction with land, stronger vertical wind shear experienced by Eline was associated with higher asymmetry and dispersion. Additionally, rain fields were less solid although the center was mostly enclosed by rain. Storm shape was altered as both storms tracked over Madagascar, with Hudah recovering more quickly. Moisture increased for both storms and shear decreased for Eline, allowing it to become more centered and solid, and grow larger. Relationships between intensity, land interaction, and rain field shape support the results of previous research and demonstrate the global utility of these metrics. Keywords: GIS; spatial analysis; tropical cyclones; rain fields Citation: Matyas, C.J.; VanSchoick, S. -

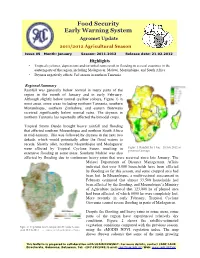

Agromet Update Issue 04

Food Security Early Warning System Agromet Update 2011/2012 Agricultural Season Issue 05 Month: January Season: 2011-2012 Release date: 21-02-2012 Highlights • Tropical cyclones, depressions and torrential rains result in flooding in several countries in the eastern parts of the region, including Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, and South Africa • Dryness negatively affects Vuli season in northern Tanzania Regional Summary Rainfall was generally below normal in many parts of the region in the month of January and in early February. Although slightly below normal (yellow colours, Figure 1) in most areas, some areas including northern Tanzania, southern Mozambique, southern Zimbabwe, and eastern Botswana received significantly below normal rains. The dryness in northern Tanzania has reportedly affected the bimodal crops. Tropical Storm Dando brought heavy rainfall and flooding that affected southern Mozambique and northern South Africa in mid-January. This was followed by dryness in the next two dekads, which would potentially allow the flood waters to recede. Shortly after, northern Mozambique and Madagascar were affected by Tropical Cyclone Funso, resulting in Figure 1. Rainfall for 1 Jan – 10 Feb 2012 as percent of average extensive flooding in some areas. Southern Malawi was also affected by flooding due to continuous heavy rains that were received since late January. The Malawi Department of Disaster Management Affairs indicated that over 5,000 households have been affected by flooding so far this season, and some cropped area had been lost. In Mozambique, a multi-sectoral assessment in February estimated that almost 33,500 households had been affected by the flooding, and Mozambique’s Ministry of Agriculture indicated that 123,000 ha of planted area had been affected, of which 6000 ha were completely lost. -

EXPERT REVIEW DRAFT IPCC SREX Chapter 9 Do Not Cite, Quote, Or

EXPERT REVIEW DRAFT IPCC SREX Chapter 9 1 Chapter 9. Case Studies 2 3 Coordinating Lead Authors 4 Gordon McBean (Canada), Virginia Murray (UK), Mihir Bhatt (India) 5 6 Lead Authors 7 Sergey Borshch (Russian Federation), Tae Sung Cheong (South Korea), Wadid Fawzy Erian (Egypt), Silvia Llosa 8 (Peru), Farrokh Nadim (Norway), Arona Ngari (Cook Islands), Mario Nunez (Argentina), Ravsal Oyun (Mongolia), 9 Avelino G. Suarez (Cuba) 10 11 Note: Also see authors and contributing authors for each case study. 12 13 14 Contents 15 16 9.1. Introduction 17 9.1.1. Description of Case Studies Approach in General 18 9.1.2. Case Study Analyses: Lessons Identified and Learned – Good and Bad Practices 19 20 9.2. Methodological Approach 21 9.2.1. Case Studies 22 9.2.2. Literature: Papers, Reports, Grey Literature 23 9.2.3. Relationship between Extreme Climate-Related Events and Climate Change 24 9.2.4. Scale 25 26 9.3. Case Studies 27 9.3.1. Extreme Events 28 – Case Study 9.1. Tropical Cyclones 29 – Case Study 9.2. Urban Heat Waves, Vulnerability and Resilience 30 – Case Study 9.3. Drought and Famine in Ethiopia in the Years 1999-2000 31 – Case Study 9.4. Sand and Dust Storms 32 – Case Study 9.5. Floods 33 – Case Study 9.6. Drought, Heat Wave, and Black Saturday Bushfires in Victoria 34 – Case Study 9.7. Dzud of 2009-2010 in Mongolia 35 – Case Study 9.8. Disastrous Epidemic Disease: The Case of Cholera 36 9.3.2. Vulnerable Regions and Populations 37 – Case Study 9.9. -

Coping with Floods – the Experience of Mozambique1

1st WARFSA/WaterNet Symposium: Sustainable Use of Water Resources, Maputo, 1-2 November 2000 COPING WITH FLOODS – THE EXPERIENCE OF MOZAMBIQUE1 Álvaro CARMO VAZ Professor, Faculty of Engineering, Eduardo Mondlane University Director, CONSULTEC – Consultores Associados Lda. e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT A summary review is made of the major floods that have occurred in Mozambique since the Independence in 1975, describing the most important negative impacts and consequences. Various types of measures for flood mitigation are analysed, considering how they have been used in past floods and their potential for coping with floods in the future. These measures are grouped into structural (dams, levees, flooding areas, river training) and non-structural measures (flood zoning, flood management, flood warning systems, emergency plans, raising awareness, insurance). The paper briefly refers the need for adequate and comprehensive reports on past floods and some related research areas. 1 THE FLOOD PRONE RIVERS OF MOZAMBIQUE More than 50% of the Mozambican territory is part of international river basins – from South to North, the Maputo, Umbeluzi, Incomati, Limpopo, Save, Buzi, Pungoé, Zambezi and Rovuma, see figures 1 and 2. All these rivers have their flood plains inside Mozambique, with the exception of the Rovuma river that forms the border between this country and Tanzania. The largest basins are the Zambezi (1,200,000 Km2) and the Limpopo (412,000 Km2) and the smallest one is the Umbeluzi (5,600 Km2) with the others ranging from about 30,000 to 150,000 Km2. The climatic conditions of Mozambique indicate that the country is subject to various types of events that can originate floods: cyclones and tropical depressions from the Indian Ocean and cold fronts from the south. -

Rhodesiana 19

PUBLICATION No. 19 DECEMBER, 1968 The Standard Bank Limited, Que Que 1968 THE PIONEER HEAD KINGSTONS LIMITED have pleasure in announcing a new venture, the re-issue of rare and elusive books of outstanding Rhodesian interest, under the imprint of the PIONEER HEAD, and through the medium of photolithography. It is also intended to publish original works of merit, of Rhodesian origin, when these are available. The first volume, in what will be known as the HERITAGE SERIES, will be the much sought-after classic, AFRICAN NATURE NOTES AND REMINISCENCES, by Frederick Courteney Selous. MR. FRANK E. READ, F.R.P.S., F.I.I.P., F.R.S.A., will be Book Architect for the whole series, and the Publishers believe that this will ensure a standard of book production never before achieved in this country. Since both the Ordinary and Collector's Editions will be strictly limited, the Publishers recommend that you place your order now. Copies can be ordered from the PIONEER HEAD, P.O. Box 591, Salisbury, or from your local Bookseller. THE REPRINT: AFRICAN NATURE NOTES AND REMINISCENCES A complete facsimile reproduction of the text of the First Edition of 1908, with the original illustrations by Edmund Caldwell, but with an additional colour frontispiece, never previously reproduced, being a portrait of Selous by Dickin son. New endpapers, reproducing, in facsimile, a letter from Selous to J. G. Millais, Author and Illustrator of "A Breath from the Veldt", and Selous' Biographer. THE EDITIONS: ORDINARY EDITION: Bound in full Buckram, identical to the original binding, lettered gilt on spine and with blind-blocking, top edge trimmed and stained. -

Mozambique Suffers Under Poor WASH Facilities and Is Prone MOZAMBIQUE to Outbreaks of Water- and Vector-Borne Diseases

ACAPS Briefing Note: Floods Briefing Note – 26 January 2017 Priorities for WASH: Provision of drinking water is needed in affected areas. humanitarian Mozambique suffers under poor WASH facilities and is prone MOZAMBIQUE to outbreaks of water- and vector-borne diseases. intervention Floods in central and southern provinces Shelter: Since October 2016, 8,162 houses have been destroyed and 21,000 damaged by rains and floods. Health: Healthcare needs are linked to the damage to Need for international Not required Low Moderate Significant Major healthcare facilities, which affects access to services. At least assistance X 30 healthcare centres have been affected. Very low Low Moderate Significant Major Food: Farmland has been affected in Sofala province, one of Expected impact X the main cereal-producing areas of a country where 1.8 million people are already facing Crisis (IPC Phase 3) levels of food Crisis overview insecurity. Since the beginning of January 2017, heavy seasonal rains have been affecting central Humanitarian Several roads and bridges have been damaged or flooded in the and southern provinces in Mozambique. 44 people have died and 79,000 have been constraints affected provinces. Some areas are only accessible by boat, and affected. The Mozambican authorities issued an orange alert for the provinces of aid has to be airdropped. Maputo, Gaza, Inhambane and Nampula, yet areas of Tete and Sofala provinces have also been affected. The orange alert means that government institutions are planning for an impending disaster. Continued rainfall has been forecasted for the first quarter of 2017. Key findings Anticipated The impact will be influenced by the capacity of the government to respond.