Land Tenure and Natural Disasters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GROWING SEASON STATUS Rainfall, Vegetation and Crop Monitoring

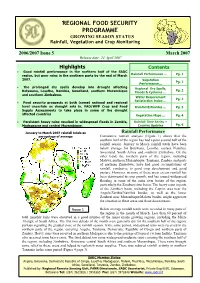

REGIONAL FOOD SECURITY PROGRAMME GROWING SEASON STATUS Rainfall, Vegetation and Crop Monitoring 2006/2007 Issue 5 March 2007 Release date: 24 April 2007 Highlights Contents • Good rainfall performance in the northern half of the SADC region, but poor rains in the southern parts by the end of March Rainfall Performance … Pg. 1 2007. Vegetation Pg. 2 Performance… • The prolonged dry spells develop into drought affecting Regional Dry Spells, Pg. 2 Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, Swaziland, southern Mozambique Floods & Cyclones … and southern Zimbabwe. Water Requirement Pg. 2 Satisfaction Index … • Food security prospects at both (some) national and regional level uncertain as drought sets in. FAO/WFP Crop and Food Rainfall Estimates … Pg. 3 Supply Assessments to take place in some of the drought affected countries Vegetation Maps … Pg. 4 • Persistent heavy rains resulted in widespread floods in Zambia, Rainfall Time Series + Madagascar and central Mozambique. Country Updates Pg. 6 January to March 2007 rainfall totals as Rainfall Performance percentage of average Cumulative rainfall analysis (Figure 1) shows that the southern half of the region has had a poor second half of the rainfall season. January to March rainfall totals have been below average for Botswana, Lesotho, eastern Namibia, Swaziland, South Africa and southern Zimbabwe. On the other hand, the northern parts of the region, including Malawi, northern Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, and parts of northern Zimbabwe, have had good accumulations of rainfall, conducive to good crop development and good pasture. However, in some of these areas excess rainfall has been detrimental to crop growth, and has caused widespread flooding in some of the main river basins of the region, particularly the Zambezi river basin. -

Impact of Droughts and Floods

Compiled by th entre fo ev 10 ment Research Sou ern Africa for the Division of Early Warning an AT-IONS ENVIRON E United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Division of Early Warning and Assessment (DEWA) UNEP Complex, Gigiri, Nairobi P.O. Box 30552, 00100, Kenya Tel: +254-20-7623785 Fax: + 254 -20- 7624309 Web: http://www.unep.org © UNEP, SARDC, 2009 ISB 978-92-807-2835-4 Information in this publication can be reproduced, used and shared, with full acknowledgement of the eo-publishers, SARDC and UNEP. Citation: CEDRISA, Droughts and Floods in Southern Africa: Environmental Change and Human Vulnerability, UNEP and SARDC, 2009 Cover and Text Design SARDC: Paul Wade and Tonely Ngwenya Print Coordination: DS Print Media, Johannesburg 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS 3 List of Tables, Boxes, Graphs, Maps and Figures 4 ACKNOWLEDG EM ENTS 5 ACRONYMS 7 INTRODUCTION 9 Water Resources in Southern Africa 9 DROUGHTS AND FLOODS IN SOUTHERN AFRICA 13 Factors that Exacerbate Droughts and Floods 13 THE 2000-2003 DROUGHTS AND FLOODS 17 Malawi 17 Mozambique " 18 Swaziland 21 Zambia 23 Zimbabwe 25 IM PACT OF DROUGHTS AND FLOODS 31 Droughts 31 Floods 35 NATIONAL RESPONSES TO DROUGHTS AND FLOODS 39 Dealing with Droughts 39 Dealing with Floods 41 National, Regional and International Obligations 44 REFERENCES 47 3 List of Tables Table I Rainfall and Evaporation Statistics of some SADC Countries 10 Table 2 Mean Annual Runoff of Selected River Basins in Southern Africa 10 Table 3 Impact of Selected 2000-2003 Floods on Malawi's Socio-Economy 18 Table 4 Flood Incidences in -

EXPERT REVIEW DRAFT IPCC SREX Chapter 9 Do Not Cite, Quote, Or

EXPERT REVIEW DRAFT IPCC SREX Chapter 9 1 Chapter 9. Case Studies 2 3 Coordinating Lead Authors 4 Gordon McBean (Canada), Virginia Murray (UK), Mihir Bhatt (India) 5 6 Lead Authors 7 Sergey Borshch (Russian Federation), Tae Sung Cheong (South Korea), Wadid Fawzy Erian (Egypt), Silvia Llosa 8 (Peru), Farrokh Nadim (Norway), Arona Ngari (Cook Islands), Mario Nunez (Argentina), Ravsal Oyun (Mongolia), 9 Avelino G. Suarez (Cuba) 10 11 Note: Also see authors and contributing authors for each case study. 12 13 14 Contents 15 16 9.1. Introduction 17 9.1.1. Description of Case Studies Approach in General 18 9.1.2. Case Study Analyses: Lessons Identified and Learned – Good and Bad Practices 19 20 9.2. Methodological Approach 21 9.2.1. Case Studies 22 9.2.2. Literature: Papers, Reports, Grey Literature 23 9.2.3. Relationship between Extreme Climate-Related Events and Climate Change 24 9.2.4. Scale 25 26 9.3. Case Studies 27 9.3.1. Extreme Events 28 – Case Study 9.1. Tropical Cyclones 29 – Case Study 9.2. Urban Heat Waves, Vulnerability and Resilience 30 – Case Study 9.3. Drought and Famine in Ethiopia in the Years 1999-2000 31 – Case Study 9.4. Sand and Dust Storms 32 – Case Study 9.5. Floods 33 – Case Study 9.6. Drought, Heat Wave, and Black Saturday Bushfires in Victoria 34 – Case Study 9.7. Dzud of 2009-2010 in Mongolia 35 – Case Study 9.8. Disastrous Epidemic Disease: The Case of Cholera 36 9.3.2. Vulnerable Regions and Populations 37 – Case Study 9.9. -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO Diploma Thesis

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Declaration I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. I agree with the placing of this thesis in the library of the Faculty of Education at the Masaryk University and with the access for academic purposes. Brno, 30th March 2018 …………………………………………. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. for his kind help and constant guidance throughout my work. Bc. Lukáš Opavský OPAVSKÝ, Lukáš. Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis; Diploma Thesis. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, English Language and Literature Department, 2018. XX p. Supervisor: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Annotation The purpose of this thesis is an analysis of a corpus comprising of opening sentences of articles collected from the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia. Four different quality categories from Wikipedia were chosen, from the total amount of eight, to ensure gathering of a representative sample, for each category there are fifty sentences, the total amount of the sentences altogether is, therefore, two hundred. The sentences will be analysed according to the Firabsian theory of functional sentence perspective in order to discriminate differences both between the quality categories and also within the categories. -

Taxing Diamonds to Reduce Unemployment in Namibia: Would It

September 2014 • Working Paper 77E Regional Inequality and Polarization in the Context of Concurrent Extreme Weather and Economic Shocks Julie A. Silva Corene J. Matyas Benedito Cunguara Julie Silva is assistant professor at the University of Maryland, Corene Matyas is associate professor at the University of Florida, and Benedito Cunguara is a research associate at Michigan State University. i DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS Report Series The Directorate of Economics of the Mozambican Ministry of Agriculture in collaboration with Michigan State University produces several publication series concerning socio- economics applied research, food security and nutrition. Publications under the Research Summary series (Flash) are short (3 - 4 pages), carefully focused reports designated to provide timely research results on issues of great interest. Publications under the Research Report Series and Working Paper Series seek to provide longer, more in depth treatment of agricultural research issues. It is hoped that these reports series and their dissemination will contribute to the design and implementation of programs and policies in Mozambique. Their publication is all seen as an important step in the Directorate’s mission to analyze agricultural policies and agricultural research in Mozambique. Comments and suggestion from interested users on reports under each of these series help to identify additional questions for consideration in later data analyses and report writing, and in the design of further research activities. Users of these reports are encouraged to submit comments and inform us of ongoing information and analysis needs. This report does not reflect the official views or policy positions of the Government of the Republic of Mozambique nor of USAID. -

Intoaction Flood-Warning System in Mozambique Completion of The

June 2007 IntoAction 2 Flood-warning system in Mozambique Completion of the Búzi project Published by the Munich Re Foundation From Knowledge to Action IntoAction 2 / Flood-warning system in Mozambique Contents Project overview – Búzi project 3 Floods in Mozambique 4 Duration Red flag signals danger 5 Success factors August 2005–December 2006 6 Flood-warning system a success! Budget 8 Chronology of Cyclone Favio 2007 50% Munich Re Foundation, 10 Learning 50% German Agency for Technical 11 Measuring Cooperation 12 Warning 13 Rescuing Continuation in Project Save Rio Save Machanga/Govurobis, 14 About Mozambique 15 as of April 2007 Our regional partners Project management Thomas Loster, Anne Wolf; on-site: Wolfgang Stiebens In Mozambique, as Village life in Búzi in many other centres on the African countries, main street. The women and girls weekly market have to fetch is inundated if water. Distances of flooding occurs. some 30 kilometres are by no means uncommon. IntoAction 2 / Flood-warning system in Mozambique Page 3 Floods in Mozambique In recent decades, there has been a This southeast African nation also had significant increase in flood disasters to contend with floods at the begin- in many parts of the world, Mozam- ning of 2007. Following weeks of rain, bique being no exception. It suffered major rivers in Central Mozambique its worst floods in recent history such as the Zambezi and the Búzi in 2000. At the heart of the country, burst their banks. Many people lost thousands of square kilometres were their lives in the worst floods the inundated and more than 700 people region had experienced for six years. -

COMMISSION DECISION of on the Financing of Humanitarian Operations from the 9Th European Development Fund in MOZAMBIQUE

COMMISSION DECISION of on the financing of humanitarian operations from the 9th European Development Fund in MOZAMBIQUE THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, Having regard to the ACP-EC Partnership Agreement signed in Cotonou on 23 June 2000, in particular Articles 721, Having regard to the Internal Agreement of 18 September 2000 on the Financing and Administration of Community Aid under the Financial Protocol to the Partnership Agreement between the African, Caribbean and Pacific States and the European Community and its Member States signed in Cotonou (Benin) on 23 June 2000, in particular Articles 24(3) a and 25(1) thereof2 Whereas: 1. Mozambique has suffered a series of climatic shocks which have had deleterious effects on the coping mechanisms of already chronically vulnerable and food insecure populations; 2. Up to 100,000 people, many still displaced in camps, are estimated to have unmet humanitarian needs, which are likely to make the recovery process very difficult; 3. Affected populations should be given the opportunity to recover their livelihoods and resettle in safety and dignity; 4. It is necessary for political and humanitarian reasons to complete the repatriation process in the shortest possible time, and in safety and dignity ; 5. An assessment of the humanitarian situation leads to the conclusion that a humanitarian aid operation should be financed by the Community for a period of 12 months ; 6. In accordance with the objectives set out in Article 72 of the ACP-EC Partnership Agreement it is estimated than an amount of EUR 3,000,000 from the 9th European Development Fund, representing less than 25% of the national Indicative Programme, is necessary to provide humanitarian assistance to up to 100,000 vulnerable people recovering and/or resettling after natural disasters ; 7. -

1 1) Tropical Cyclone Favio 2) Zambezi Floods

UNICEF Situation Report MOZAMBIQUE 15-18 March 2007 Major Developments An Inter-Agency Real-Time Evaluation (IA-RTE) will be conducted in Mozambique in the last week of March, at the recommendation of the Regional Director’s Team members of RIACSO, the regional IASC forum, with strong support from the IASC Humanitarian Country Team. The evaluation will be conducted over a period of three to four weeks by a team of four people, including two national consultants. The primary objective of the IA-RTE is twofold: (1) to assess the overall appropriateness, coherence, timeliness and effectiveness of the response, in the context of humanitarian reform, and (2) to provide real-time feedback to support senior management decision-making and to facilitate planning and implementation. The time period to be covered by the evaluation is February - April 2007. The IA-RTE will look at pre- emergency issues such as contingency planning and preparedness and how these affected the response, as well as assessing real-time response issues with a focus on the broader humanitarian response provided by both national and international actors as well as the involvement and perspectives of the affected population. The national Vulnerability Assessment Committee (VAC) under the Technical Secretariat for Food Security and Nutrition, together with other partners, is planning a rapid food security assessment in flood, cyclone and drought affected areas. The Terms of Reference and data collection tools for the assessment are currently being finalised and the data collection is planned to commence on 10 April, with training in the use of tools being conducted from 2-9 April. -

Relating Rainfall Patterns to Agricultural Income: Implications for Rural Development in Mozambique

AMERICAN METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY Weather, Climate, and Society EARLY ONLINE RELEASE This is a preliminary PDF of the author-produced manuscript that has been peer-reviewed and accepted for publication. Since it is being posted so soon after acceptance, it has not yet been copyedited, formatted, or processed by AMS Publications. This preliminary version of the manuscript may be downloaded, distributed, and cited, but please be aware that there will be visual differences and possibly some content differences between this version and the final published version. The DOI for this manuscript is doi: 10.1175/WCAS-D-13-00012.1 The final published version of this manuscript will replace the preliminary version at the above DOI once it is available. If you would like to cite this EOR in a separate work, please use the following full citation: Silva, J., and C. Matyas, 2013: Relating Rainfall Patterns to Agricultural Income: Implications for Rural Development in Mozambique. Wea. Climate Soc. doi:10.1175/WCAS-D-13-00012.1, in press. © 2013 American Meteorological Society Manuscript (non-LaTeX) Click here to download Manuscript (non-LaTeX): AMS_resubmission_2013_07_11_v2.doc 1 Relating Rainfall Patterns to Agricultural 2 Income: Implications for Rural Development in 3 Mozambique 4 5 6 Julie A. Silva1 7 Department of Geographical Sciences, 8 University of Maryland, College Park 9 10 11 Corene J. Matyas 12 Department of Geography, University of Florida 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 Corresponding author address: Julie Silva, Department of Geographical Sciences, 32 University of Maryland, College Park, 2181 Lefrak Hall, College Park, MD 20742, USA. -

The Global Climate System Review 2003

The Global Climate System Review 2003 SI m* mmmnrm World Meteorological Organization Weather • Climate • Water WMO-No. 984 socio-economic development - environmental protection - water resources management The Global Climate System Review 2003 Bfâ World Meteorological Organization Weather • Climate • Water WMO-No. 984 Front cover: Europe experienced a historic heat wave during the summer of 2003. Compared to the long-term climatological mean, temperatures in July 2003 were sizzling. The image shows the differences in daytime land surface temperatures of 2003 to the ones collected in 2000. 2001. 2002 and 2004 by the moderate imaging spectroradiomeier (MODISj on NASA's Terra satellite. (NASA image courtesy of Reto Stôckli and Robert Simmon, NASA Earth Observatory) Reference: Thus publication was adapted, with permission, from the "State of the Climate for 2003 "• published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Volume 85. Number 6. J'une 2004, S1-S72. WMO-No. 984 © 2005, World Meteorological Organization ISBN 92-63-10984-2 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Contents Page Authors 5 Foreword Chapter 1: Executive Summary 1.1 Major climate anomalies and episodic events 1.2 Chapter 2: Global climate 9 1.3 Chapter 3: Trends in trace gases 9 1.4 Chapter 4: The tropics 10 1.5 Chapter 5: Polar climate 10 1.6 Chapter 6: Regional climate 11 Chapter 2: Global climate 12 2.1 Global surface temperatures ... -

The Effectiveness of Foreign Military Assets in Natural Disaster Response

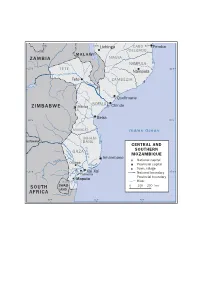

30°E 35°E Lichinga CABO 40°E Pemba DELGADO M A L A W I ZAMBIA NIASSA NAMPULA 15°S TETE 15°S Nampula Tete ZAMBÉZIA Zambezi Quelimane SOFALA ZIMBABWE Manica Chinde Beira 20°S 20°S MANICA Indian Ocean INHAM- BOTSWANA BANE CENTRAL AND Chang Indian Ocean Limpopo G A Z A SOUTHERN ane MOZAMBIQUE Inhambane National capital Olifants Chókwè Provincial capital Incomáti Town, village 25°S Xai Xai 25°S Palmeira National boundary Maputo Provincial boundary Umbeluzi River SOUTH SWAZI- 0 100 200 km AFRICA LAND 30°E 35°E 40°E Annex A Case study: Floods and cyclones in Mozambique, 2000 In January and February 2000 prolonged heavy rains and the cyclones Connie and Eline caused catastrophic flooding in Mozambique’s Gaza, Inhambane, Manica, Maputo and Sofala provinces. An estimated 2 million people were affected, 544 000 were displaced and 699 were killed. The World Bank estimated the economic damage caused by the floods and cyclones to be approximately 20 per cent of the country’s gross national product.1 Mozambique’s recently created disaster management structure was quickly overwhelmed by the scale of the humanitarian crisis. A major international assistance effort included foreign military assets from 11 countries. These countries eventually allowed their assets to be under United Nations coordination to an unprecedented degree. It was the first time that the concept of a Joint Logistics Operation Centre to manage and coordinate air assets was applied in a natural disaster response. Another similar bout of flooding in the country in 2007 provides a useful comparison of the responses and some indication of how, and how far, the lessons of 2000 have been applied. -

Independent Evaluation of Expenditure of DEC Mozambique Floods Appeal Funds March to December 2000 Volume One: Main Report

Independent Evaluation of Expenditure of DEC Mozambique Floods Appeal Funds March to December 2000 Volume One: Main Report This evaluation is published in two volumes, of which this is the first. Volume one contains the main findings of the evaluation including the executive summary. Volume two contains the appendices including the detailed beneficiary study and the summaries of the activities of the DEC agencies. Each agency summary looks at key issues relating to the performance of the agencies as well as presenting general data about their programme. The executive summary has also been published as a stand- alone document. Independent evaluation conducted by Valid International and ANSA Valid, 3 Kames Close Oxford, OX4 3LD UK Tel: +44 1865 395810 Email: [email protected] http://www.validinternational.org © 2001 Disasters Emergency Committee 52 Great Portland Street London, W1W 7HU Tel: +44 20 7580 6550 Fax: +44 20 7580 2854 Website: http://www.dec.org.uk Further details about this and other DEC evaluations can be found at the DEC website. Evaluation of DEC Mozambique Floods Appeal Page 2 Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge the more than four hundred people who gave their time to answer the evaluation team’s questions. Special thanks are due for the full and generous assistance received from the DEC agencies in Mozambique during the evaluation. Not only did the evaluation team receive full and detailed answers to their many questions, but also received the full assistance of the DEC agencies in visiting many project sites throughout the county. Evaluation Data Sheet Title: Independent Evaluation of Expenditure of DEC Mozambique Floods Appeal Funds – March to December 2000 Client: Disasters Emergency Committee http://www.dec.org.uk Date: 23 July 2001 Total pages: 94.