Inter-Agency Real-Time Evaluation of the Response to the February 2007 Floods and Cyclone in Mozambique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GROWING SEASON STATUS Rainfall, Vegetation and Crop Monitoring

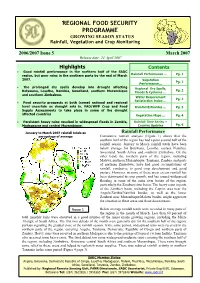

REGIONAL FOOD SECURITY PROGRAMME GROWING SEASON STATUS Rainfall, Vegetation and Crop Monitoring 2006/2007 Issue 5 March 2007 Release date: 24 April 2007 Highlights Contents • Good rainfall performance in the northern half of the SADC region, but poor rains in the southern parts by the end of March Rainfall Performance … Pg. 1 2007. Vegetation Pg. 2 Performance… • The prolonged dry spells develop into drought affecting Regional Dry Spells, Pg. 2 Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, Swaziland, southern Mozambique Floods & Cyclones … and southern Zimbabwe. Water Requirement Pg. 2 Satisfaction Index … • Food security prospects at both (some) national and regional level uncertain as drought sets in. FAO/WFP Crop and Food Rainfall Estimates … Pg. 3 Supply Assessments to take place in some of the drought affected countries Vegetation Maps … Pg. 4 • Persistent heavy rains resulted in widespread floods in Zambia, Rainfall Time Series + Madagascar and central Mozambique. Country Updates Pg. 6 January to March 2007 rainfall totals as Rainfall Performance percentage of average Cumulative rainfall analysis (Figure 1) shows that the southern half of the region has had a poor second half of the rainfall season. January to March rainfall totals have been below average for Botswana, Lesotho, eastern Namibia, Swaziland, South Africa and southern Zimbabwe. On the other hand, the northern parts of the region, including Malawi, northern Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, and parts of northern Zimbabwe, have had good accumulations of rainfall, conducive to good crop development and good pasture. However, in some of these areas excess rainfall has been detrimental to crop growth, and has caused widespread flooding in some of the main river basins of the region, particularly the Zambezi river basin. -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO Diploma Thesis

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Declaration I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. I agree with the placing of this thesis in the library of the Faculty of Education at the Masaryk University and with the access for academic purposes. Brno, 30th March 2018 …………………………………………. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. for his kind help and constant guidance throughout my work. Bc. Lukáš Opavský OPAVSKÝ, Lukáš. Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis; Diploma Thesis. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, English Language and Literature Department, 2018. XX p. Supervisor: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Annotation The purpose of this thesis is an analysis of a corpus comprising of opening sentences of articles collected from the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia. Four different quality categories from Wikipedia were chosen, from the total amount of eight, to ensure gathering of a representative sample, for each category there are fifty sentences, the total amount of the sentences altogether is, therefore, two hundred. The sentences will be analysed according to the Firabsian theory of functional sentence perspective in order to discriminate differences both between the quality categories and also within the categories. -

Taxing Diamonds to Reduce Unemployment in Namibia: Would It

September 2014 • Working Paper 77E Regional Inequality and Polarization in the Context of Concurrent Extreme Weather and Economic Shocks Julie A. Silva Corene J. Matyas Benedito Cunguara Julie Silva is assistant professor at the University of Maryland, Corene Matyas is associate professor at the University of Florida, and Benedito Cunguara is a research associate at Michigan State University. i DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS Report Series The Directorate of Economics of the Mozambican Ministry of Agriculture in collaboration with Michigan State University produces several publication series concerning socio- economics applied research, food security and nutrition. Publications under the Research Summary series (Flash) are short (3 - 4 pages), carefully focused reports designated to provide timely research results on issues of great interest. Publications under the Research Report Series and Working Paper Series seek to provide longer, more in depth treatment of agricultural research issues. It is hoped that these reports series and their dissemination will contribute to the design and implementation of programs and policies in Mozambique. Their publication is all seen as an important step in the Directorate’s mission to analyze agricultural policies and agricultural research in Mozambique. Comments and suggestion from interested users on reports under each of these series help to identify additional questions for consideration in later data analyses and report writing, and in the design of further research activities. Users of these reports are encouraged to submit comments and inform us of ongoing information and analysis needs. This report does not reflect the official views or policy positions of the Government of the Republic of Mozambique nor of USAID. -

Intoaction Flood-Warning System in Mozambique Completion of The

June 2007 IntoAction 2 Flood-warning system in Mozambique Completion of the Búzi project Published by the Munich Re Foundation From Knowledge to Action IntoAction 2 / Flood-warning system in Mozambique Contents Project overview – Búzi project 3 Floods in Mozambique 4 Duration Red flag signals danger 5 Success factors August 2005–December 2006 6 Flood-warning system a success! Budget 8 Chronology of Cyclone Favio 2007 50% Munich Re Foundation, 10 Learning 50% German Agency for Technical 11 Measuring Cooperation 12 Warning 13 Rescuing Continuation in Project Save Rio Save Machanga/Govurobis, 14 About Mozambique 15 as of April 2007 Our regional partners Project management Thomas Loster, Anne Wolf; on-site: Wolfgang Stiebens In Mozambique, as Village life in Búzi in many other centres on the African countries, main street. The women and girls weekly market have to fetch is inundated if water. Distances of flooding occurs. some 30 kilometres are by no means uncommon. IntoAction 2 / Flood-warning system in Mozambique Page 3 Floods in Mozambique In recent decades, there has been a This southeast African nation also had significant increase in flood disasters to contend with floods at the begin- in many parts of the world, Mozam- ning of 2007. Following weeks of rain, bique being no exception. It suffered major rivers in Central Mozambique its worst floods in recent history such as the Zambezi and the Búzi in 2000. At the heart of the country, burst their banks. Many people lost thousands of square kilometres were their lives in the worst floods the inundated and more than 700 people region had experienced for six years. -

COMMISSION DECISION of on the Financing of Humanitarian Operations from the 9Th European Development Fund in MOZAMBIQUE

COMMISSION DECISION of on the financing of humanitarian operations from the 9th European Development Fund in MOZAMBIQUE THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, Having regard to the ACP-EC Partnership Agreement signed in Cotonou on 23 June 2000, in particular Articles 721, Having regard to the Internal Agreement of 18 September 2000 on the Financing and Administration of Community Aid under the Financial Protocol to the Partnership Agreement between the African, Caribbean and Pacific States and the European Community and its Member States signed in Cotonou (Benin) on 23 June 2000, in particular Articles 24(3) a and 25(1) thereof2 Whereas: 1. Mozambique has suffered a series of climatic shocks which have had deleterious effects on the coping mechanisms of already chronically vulnerable and food insecure populations; 2. Up to 100,000 people, many still displaced in camps, are estimated to have unmet humanitarian needs, which are likely to make the recovery process very difficult; 3. Affected populations should be given the opportunity to recover their livelihoods and resettle in safety and dignity; 4. It is necessary for political and humanitarian reasons to complete the repatriation process in the shortest possible time, and in safety and dignity ; 5. An assessment of the humanitarian situation leads to the conclusion that a humanitarian aid operation should be financed by the Community for a period of 12 months ; 6. In accordance with the objectives set out in Article 72 of the ACP-EC Partnership Agreement it is estimated than an amount of EUR 3,000,000 from the 9th European Development Fund, representing less than 25% of the national Indicative Programme, is necessary to provide humanitarian assistance to up to 100,000 vulnerable people recovering and/or resettling after natural disasters ; 7. -

1 1) Tropical Cyclone Favio 2) Zambezi Floods

UNICEF Situation Report MOZAMBIQUE 15-18 March 2007 Major Developments An Inter-Agency Real-Time Evaluation (IA-RTE) will be conducted in Mozambique in the last week of March, at the recommendation of the Regional Director’s Team members of RIACSO, the regional IASC forum, with strong support from the IASC Humanitarian Country Team. The evaluation will be conducted over a period of three to four weeks by a team of four people, including two national consultants. The primary objective of the IA-RTE is twofold: (1) to assess the overall appropriateness, coherence, timeliness and effectiveness of the response, in the context of humanitarian reform, and (2) to provide real-time feedback to support senior management decision-making and to facilitate planning and implementation. The time period to be covered by the evaluation is February - April 2007. The IA-RTE will look at pre- emergency issues such as contingency planning and preparedness and how these affected the response, as well as assessing real-time response issues with a focus on the broader humanitarian response provided by both national and international actors as well as the involvement and perspectives of the affected population. The national Vulnerability Assessment Committee (VAC) under the Technical Secretariat for Food Security and Nutrition, together with other partners, is planning a rapid food security assessment in flood, cyclone and drought affected areas. The Terms of Reference and data collection tools for the assessment are currently being finalised and the data collection is planned to commence on 10 April, with training in the use of tools being conducted from 2-9 April. -

Floods, Cyclones and Droughts That Draw Back the Government Efforts in the Fight Against Poverty, Negatively Impacting the Country’S Socioeconomic Status

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE HUMANITARIAN/RESIDENT COORDINATOR ON THE USE OF CERF GRANTS Country Mozambique Humanitarian / Resident Mr. Ndolamb Ngokwey Coordinator Reporting Period January 2007 / December 2007 I. Background Mozambique is prone to a wide range of natural disasters, mainly floods, cyclones and droughts that draw back the Government efforts in the fight against poverty, negatively impacting the country’s socioeconomic status. On 4 February 2007, the Mozambique National Disaster Management Institute (INGC) declared a “red alert” calling for the evacuation of communities along the Zambezi River Basin, as rising water levels threatened to flood low-lying areas. Heavy rains in the Mozambican territory created this threat, as well as in the neighboring countries of Zambia and Malawi, which also feed the Zambezi River and its tributaries. An estimated 285,000 people were affected by the floods; out of these, 163,000 were displaced to accommodation centres whilst some were allocated to resettlement centres previously created after the 2001 flood emergency. Additionally, on 22 February 2007, the coastal area of Mozambique was hit by another natural disaster, cyclone Favio which made landfall in Vilanculos, in the coastal province of Inhambane. An estimated 150,000 people were affected by the cyclone. Essential infrastructure, as well as health centres and educational facilities in those affected areas were severely damaged. Thousands of hectares of crops were also destroyed. The Government of Mozambique (GoM), through the INGC coordination and with the support of line ministries at national, provincial and district levels, led the emergency response process in both the flood and cyclone emergencies. INGC activated national and regional emergency operations centres (CENOEs) in order to ensure the effective coordination of evacuation, rescue and relief operations carried out by national and international, civil and military actors. -

Cyclones and Storms February 23, 2007

sd UNCLASSIFIED/FOUO Mozambique: Cyclones and Storms February 23, 2007 (U) SITUATION REPORT: Three storms are 0 50 100 200 300 400 500 Km heading towards Mozambique: 1) Cyclone Favio is a category 4 storm with winds of 144 mph and HUMANITAIRIANU made landfall near Vilanculos during the night of INFORMATION Feb 21. 2) Cyclone Gamede has winds of 52 Radar image acquired UNIT mph and is expected to make landfall further Cyclone Cyclone Unnamed Feb 22 1330Z U.S Department of State north. 3) An as-yet-named storm is expected to MALAWI Gamede [email protected] follow on the heels of the two cyclones. The Favio http://hiu.state.gov storms could hit at least one of Mozamique's Lilongwe three largest cities -- Maputo (1 million), Beira (300,Z000A), NMampuBla (I20A0,000). 15°S Cahora Bassa Nampula Dam Lusaka MOZAMBIQUE Zambezi River Harare MADAGASCAR Toamasina ZIMBABWE Antananarivo 20°S Beira 20°S Bulawayo el Cyclone Favio (U) IMPACTS: When Favio made landfall in Inhambane, strong winds damaged 02/22/1330Z P MozCamhabniqnue Save River a infrastructure, including power, disrupting / th mobile coverage and municipal water supply, Vilanculos o roof damage to concrete structures on the f waterside, and destruction of mud and reed C huts. Across southern Mozambique and Limpopo River yc southeastern Zimbabwe, torrential rains are 02/21/1830Z l expected through Feb 25. These rains, on coupled with rain associated with the / e Toliara cyclones could increase water levels in the Inhambane F already flooded Limpopo and Zambezi river SOUTH 02/21/00Z a basins. According to NGOs, the flooding vi could impact up to 285,000 people. -

Assessment Report on Mainstreaming and Implementing Disaster Risk Reduction in Mozambique

Assessment report on mainstreaming and implementing disaster risk reduction in Mozambique Assessment report on mainstreaming and implementing disaster risk reduction in Mozambique Ordering information To order copies of Assessment report on mainstreaming and implementing disaster risk reduction in Mozambique by the Economic Commission for Africa, please contact: Publications Economic Commission for Africa P.O. Box 3001 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Tel: +251 11 544-9900 Fax: +251 11 551-4416 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.uneca.org © United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, 2015 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia All rights reserved First printing October, 2015 Language: Original- French ISBN: 978-99944-61-65-3 eISBN: 978-99944-62-65-0 Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted. Acknowledgement is requested, together with a copy of the publication. Designed and printed by the ECA Publishing and Distribution Unit. ISO 14001:2004 certified. Layout: Godfrey Munanga - UNON, Publishing Services Section, Nairobi, ISO 14001:2004-Certified. Assessment report on mainstreaming and implementing disaster risk reduction in Mozambique Table of contents Acronyms and abbreviations v Acknowledgements vii Executive summary viii 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Conceptual framework and methodology 2 1.3 Report outline 4 2. Review of national disaster risks 5 2.1 Overview of main hazards in Mozambique 5 2.2 Key socioeconomic and environmental disaster impacts 10 3. Review of main past and ongoing DRR interventions 12 3.1 Establishment of institutional and strategic DRR frameworks 12 3.2 DRR programmes and projects 16 4. Mainstreaming and implementation of DRR within national plans and strategies 20 4.1 Overview of key mainstreaming frameworks 20 4.2 Mainstreaming of DRR in different frameworks 21 4.3 DRR implementation strategy and stakeholders 24 5. -

Annual Review 2007

Annual Review 2007 EUROPEAN COMMISSION *** ** ** **** * Humanitarian Aid 25 Format: (210.00 x 297.00 mm); Date: Apr 16, 2008 16:33:06; Output Profile: CMYK ISO Uncoated Annual review 2007 Contents Contents Message from Commissioner Louis Michel 1 Key events in 2007 2 Features European Consensus on Humanitarian Aid 4 Bangladesh: Battling the elements 5 Middle East: Being a refugee 6 Global reach Humanitarian funding by country, territory and region 7 Thematic funding 17 Disaster preparedness 18 Food aid 19 Sudan: Displaced in Darfur 20 Peru: “I just called to say … I’m alive” 21 Sahel: A plan and the “magic potion” 22 Facts and fi gures Facts and fi gures 23 Who’s who in DG ECHO 24 Useful web links 25 Publisher: António Cavaco, Director-General, European Commission, Directorate-General for Humanitarian Aid (ECHO) Text and coordination: ‘Information and Communication’ Unit (ECHO A.5) Format: (210.00 x 297.00 mm); Date: Apr 16, 2008 16:36:10; Output Profile: CMYK ISO Uncoated Message from the Commissioner "As the largest relief donor, the European Union has a special responsibility" 2007 was characterised by an upsurge in natural dis- asters. The lives and livelihoods of millions of people were shattered as devastating fl oods and storms struck a swathe of countries across Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. Climate change is to blame… For the fi rst time since records began, two category fi ve storms – the most powerful on the scale – developed in a single Atlantic hurricane season. Severe drought affected other regions in the world, bringing misery and ted fully to living up to this responsibility. -

Madagascar: Cyclone Indlala; Appeal No

MADAGASCAR: Preliminary Appeal no. MDRMG002 (GLIDE no. TC-2007-000034-MDG) CYCLONE INDLALA 22 March 2007 The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organization and its millions of volunteers are active in over 185 countries. For more information: www.ifrc.org In Brief THIS PRELIMINARY EMERGENCY APPEAL SEEKS CHF 773,262 (USD 637,935 OR EUR 477,765) IN CASH, KIND, OR SERVICES TO ASSIST 32,000 BENEFICIARIES (6,200 HOUSEHOLDS) FOR 6 MONTHS <click here to view the budget> A total of CHF 185,000 has been released from the Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the delivery of humanitarian assistance for this operation. Unearmarked funds to reimburse the DREF are encouraged. This operation is aligned with the International Federation's Global Agenda, which sets out four broad goals to meet the Federation's mission to "improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity". Global Agenda Goals: · Reduce the numbers of deaths, injuries and impact from disasters. · Reduce the number of deaths, illnesses and impact from diseases and public health emergencies. · Increase local community, civil society and Red Cross Red Crescent capacity to address the most urgent situations of vulnerability. · Reduce intolerance, discrimination and social exclusion and promote respect for diversity and human dignity. All International Federation assistance seeks to adhere to the Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO's) in Disaster Relief and is committed to the Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Disaster Response (Sphere) in delivering assistance to the most vulnerable. -

The Effectiveness of Foreign Military Assets in Natural Disaster Response

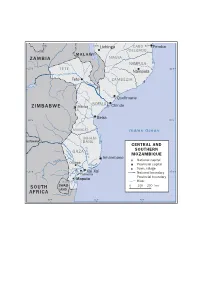

30°E 35°E Lichinga CABO 40°E Pemba DELGADO M A L A W I ZAMBIA NIASSA NAMPULA 15°S TETE 15°S Nampula Tete ZAMBÉZIA Zambezi Quelimane SOFALA ZIMBABWE Manica Chinde Beira 20°S 20°S MANICA Indian Ocean INHAM- BOTSWANA BANE CENTRAL AND Chang Indian Ocean Limpopo G A Z A SOUTHERN ane MOZAMBIQUE Inhambane National capital Olifants Chókwè Provincial capital Incomáti Town, village 25°S Xai Xai 25°S Palmeira National boundary Maputo Provincial boundary Umbeluzi River SOUTH SWAZI- 0 100 200 km AFRICA LAND 30°E 35°E 40°E Annex A Case study: Floods and cyclones in Mozambique, 2000 In January and February 2000 prolonged heavy rains and the cyclones Connie and Eline caused catastrophic flooding in Mozambique’s Gaza, Inhambane, Manica, Maputo and Sofala provinces. An estimated 2 million people were affected, 544 000 were displaced and 699 were killed. The World Bank estimated the economic damage caused by the floods and cyclones to be approximately 20 per cent of the country’s gross national product.1 Mozambique’s recently created disaster management structure was quickly overwhelmed by the scale of the humanitarian crisis. A major international assistance effort included foreign military assets from 11 countries. These countries eventually allowed their assets to be under United Nations coordination to an unprecedented degree. It was the first time that the concept of a Joint Logistics Operation Centre to manage and coordinate air assets was applied in a natural disaster response. Another similar bout of flooding in the country in 2007 provides a useful comparison of the responses and some indication of how, and how far, the lessons of 2000 have been applied.