Housing, Equality and Choice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Profumo Affair in Popular Culture: the Keeler Affair (1963) and 'The

Contemporary British History ISSN: 1361-9462 (Print) 1743-7997 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fcbh20 The Profumo affair in popular culture: The Keeler Affair (1963) and ‘the commercial exploitation of a public scandal’ Richard Farmer To cite this article: Richard Farmer (2016): The Profumo affair in popular culture: The Keeler Affair (1963) and ‘the commercial exploitation of a public scandal’, Contemporary British History, DOI: 10.1080/13619462.2016.1261698 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2016.1261698 © 2016 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 29 Nov 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 143 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fcbh20 Download by: [University of East Anglia Library] Date: 16 December 2016, At: 03:30 CONTEMPORARY BRITISH HISTORY, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2016.1261698 OPEN ACCESS The Profumo affair in popular culture: The Keeler Affair (1963) and ‘the commercial exploitation of a public scandal’ Richard Farmer Department of Film, Television and Media Studies, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This article demonstrates that the Profumo affair, which obsessed Profumo affair; satire; Britain for large parts of 1963, was not simply a political scandal, but cinema; Christine Keeler; was also an important cultural event. Focussing on the production scandal of The Keeler Affair, a feature film that figured prominently in contemporary coverage of the scandal but which has been largely overlooked since, the article shows that this film emerged from a situation in which cultural entrepreneurs, many of them associated with the satire boom, sought to exploit the scandal for financial gain. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} When the Heart Lies by Christina North 7 Things That Make up a Christian Heart

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} When the Heart Lies by Christina North 7 Things That Make Up a Christian Heart. Matthew 6:21 says, “For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.” This verse is saying that you must have honesty within your heart. Be true to yourself and those around you – and you’ll discover that your heart will guide you when you’re feeling left astray or at bay from everything that’s near and dear to you. Always listen to your heart because it will help to cultivate your decisions between right and wrong. Proverbs 3:5 says, “Trust in the Lord with all your heart and lean not on your own understanding,” This verse is conveying the desperate need for faith within your heart. There will be challenging times that cause you to question your faith and your overall belief system; however, it’s important to have faith within your heart. When you find yourself in doubt, look to your heart to guide you into the right direction. If you have these seven elements within your heart, you’ll find that your life is much fuller – full of happiness, love and the Lord. Everyone’s heart has many other qualities and attributes that furnish their individuality however, these seven elements are the core to a Christian heart. Christine Keeler obituary: the woman at the heart of the Profumo affair. There were many victims of the Profumo affair, the sex and spying scandal that dominated the headlines in 1963, contributed to the resignation of the then prime minister, Harold Macmillan, soon afterwards, and still looms disproportionately large in the history of modern Britain. -

Brian Klug What Do We Mean When We Say 'Antisemitsm'?

Brian Klug What Do We Mean When We Say ‘Antisemitsm’? Echoes of shattering glass Proceedings / International conference “Antisemitism in Europe Today: the Phenomena, the Conflicts” 8–9 November 2013 Organized by the Jewish Museum Berlin, the Foundation “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future” and the Center for Research on Antisemitism Berlin BRIAN KLUG What Do We Mean When We Say ‘Antisemitism’? 1 Brian Klug What Do We Mean When We Say ‘Antisemitism’? Echoes of shattering glass Guten abend. Let me begin by apologizing for the fact that those might be the only words in German that you hear from me this evening. I really have no excuse. I learned German – twice: once at the University of Vienna and again at the University of Chicago. And I forgot it – twice. Which goes to show that Klug by name does not necessarily mean Klug by nature. I grew up in London. My parents spoke Yiddish at home, which should have given me a solid foundation for speaking German. But, like many Jewish parents of their generation, they did so in order not to be understood by the children. And they succeeded. So, thank you, in advance, for listening. Let me also express my thanks to my hosts for their invitation, especially for inviting me to speak here and now: here, in Berlin, at the Jewish Museum, an institution that I admire immensely, and now, on the eve of the 75th anniversary of Pogromnacht, which took place across Nazi Germany and Austria on 9 November 1938. (In Britain, we still say ‘Kristallnacht’. I know and I respect the reasons why this word has been retired in Germany, and in my lecture tonight I shall use the name Pogromnacht. -

Western Europe

Western Europe Great Britain* JLHE PERIOD under review (July 1, 1962, to December 31, 1963) was an eventful one in British political and economic life. Economic recession and an exceptionally severe winter raised the number of unemployed in Jan- uary 1963 to over 800,000, the highest figure since 1939. In the same month negotiations for British entry into the European Common Market broke down, principally because of the hostile attitude of President Charles de Gaulle of France. Official opinion had stressed the economic advantages of union, but enthusiasm for the idea had never been widespread, and there was little disappointment. In fact, industrial activity rallied sharply as the year progressed. In March 1963 Britain agreed to the dissolution of the Federation of Rho- desia and Nyasaland, which had become inevitable as a result of the transfer of power in Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia to predominantly African governments and the victory of white supremacists in the elections in South- ern Rhodesia, where the European minority still retained power. Local elections in May showed a big swing to Labor, as did a series of par- liamentary by-elections. A political scandal broke out in June, when Secretary for War John Pro- fumo resigned after confessing that he had lied to the House of Commons concerning his relations with a prostitute, Christine Keeler. A mass of infor- mation soon emerged about the London demimonde, centering on Stephen Ward, an osteopath, society portrait painter, and procurer. His sensational trial and suicide in August 1963 were reported in detail in the British press. A report issued in September by Lord Denning (one of the Law Lords) on the security aspects of the scandal disposed of some of the wilder rumors of immorality in high places but showed clearly the failure of the government to deal with the problem of a concurrent liaison between the war minister's mistress and a Soviet naval attache. -

Artistes Featured on the ‘Profumo the Musical’ CD

Artistes featured on the ‘Profumo the Musical’ CD Michael Mclean as John Profumo Michael studied at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. His theatrical career as an actor and director has literally taken him around the world, with tours to Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Korea, The Philippines, Norway, Europe and numerous seasons in London’s West End. His extensive credits include ‘Sweeney Todd in Sweeney Todd’, ‘Albin in La Cage Aux Folles’, ‘Jean Valjean in Les Miserables’, ‘Walter de Courcey in Chess’, and many others. In addition Michael has directed six separate productions of ‘Phantom of the Opera’ in Japan and national tours of ‘Chicago’ and ‘Evita’ in New Zealand. Michael has appeared in many British television and film roles and his recording credits include work with the London Symphony Orchestra, the London City Orchestra and the BBC Concert Orchestra. He is also a regular broadcaster for BBC Radio 2 and BBC Radio 4. Michael has been teaching singing for over twenty years and regularly gives master classes in both singing and audition techniques to amateur, professional and educational groups throughout the United Kingdom and in Europe. Annette Yeo as Valerie Hobson Annette was born in Kent, South East England, and began training as a classical singer at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, London. She trained at Mountview Theatre drama school and went on to her first West End theatre role in the award winning 'City of Angels'. Annette has had a long and successful career as a musical theatre actor and concert singer, performing in numerous West End shows including ; 'Les Miserables', 'The Phantom of the Opera', 'Kiss Me Kate' and 'Mamma Mia'. -

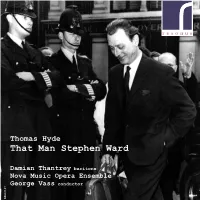

That Man Stephen Ward

Thomas Hyde That Man Stephen Ward Damian Thantrey baritone Nova Music Opera Ensemble George Vass conductor RES10197 Thomas Hyde That Man Stephen Ward One-man Opera by Thomas Hyde That Man Stephen Ward Libretto by David Norris 1. Scene 1: Consultation [10:12] Op. 8 (2006-07) 2. Scene 2: Conversation [9:07] Damian Thantrey baritone (Stephen Ward) 3. Scene 3: Congregation [10:03] Nova Music Opera Ensemble 4. Scene 4: Consternation [10:30] Kathryn Thomas flute Catriona Scott clarinet 5. Scene 5: Condemnation [10:42] Madeleine Easton violin Amy Jolly cello 6. Scene 6: Consummation [12:19] Timothy End piano & keyboard Jonny Grogan percussion Total playing time [62:57] George Vass conductor About That Man Stephen Ward: World premiere recording ‘[...] a score that deftly conjures up the songs and dances of the era, but also has an apt, brittle edge’ The Times ‘With a modest but punchy chamber ensemble conducted by George Vass, it turned small history into surprisingly large musical gestures’ Opera Now Synopsis Scene 4: Consternation A few minutes later. Johnny Edgecombe, an Scene 1: Consultation ex-boyfriend of Christine, furious at having Harley Street, London. 1963. been dumped by her, has shot at Ward’s Society osteopath Dr Stephen Ward is front door demanding to speak to Christine. attending to his patient Lord Bill Astor. Ward The police arrive to take names and statements. refers to their many mutual friends and the They turn a blind eye to the more distinguished meaning of friendship. But Bill asks for the guests, but notice there are a lot of girls about. -

The 'Wandering Jew'

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Disciplines provided by UWL Repository Jeremy Strong | University of West London, UK THE ‘WANDERING JEW’: HISTORY, FICTION, AND ADAPTATION The paper discusses the figure of the ‘Wandering Jew’ in the practice of adaptation – from page to screen – and uncovers a stereotype that finds expression in both fictional texts and in accounts of real life individuals his paper starts with a coincidence. In 2011 I attended a presentation by Prof. Peter Luther T on London’s slum landlords, and particularly Peter Rachman. The next day, through the lottery that is Britain’s ‘Love Film’ DVD rental service, I received the movie An Education, adapted from Lynn Barber’s memoir; a story in which the infamous property magnate Rachman plays a minor part. Luther argued persuasively that Rachman, although undoubtedly an unscrupulous landlord, was not quite the singular arch villain that contemporary accounts and posterity had made him. Using the figure of Rachman as a way into a wider examination of historical and fictional representations, I examine adaptation in more than one sense. In the first, straightforward, sense it is focused on two screen adaptations – An Education (Scherfig, 2009) andThe Way We Live Now (Yates, 2001). It also employs two contemporary reviews of those texts to analyse the choices made in adaptation and the responses they foster. The selection of reviews – one from a website focused on Jewish concerns, the other from a deeply unpleasant white-supremacist website – is wilful, but hopefully illuminating. Specifically, I consider the adaptations in respect of their susceptibility to either provoke the charge of anti-Semitism or nourish an anti-Semitic reading. -

East End Murders : from Jack the Ripper to Ronnie Kray Pdf, Epub, Ebook

EAST END MURDERS : FROM JACK THE RIPPER TO RONNIE KRAY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Neil Storey | 160 pages | 01 Jan 2009 | The History Press Ltd | 9780750950695 | English | Stroud, United Kingdom East End Murders : From Jack the Ripper to Ronnie Kray PDF Book Some wear and discolouring to page edges due to age. In the case of the Ripper, for instance, Long notes that arguably another victim was Sir Charles Warren, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, for his 'inability to find the killer led to him being forced out of office by public opinion'. His features had become much coarser, his neck and jaw line altered; the flesh around his eyes tightened in. The biggest city in Britain, it acted as a magnet, drawing into its fold those anxious to make money without the respectable inconvenience of working for it. He became obsessively cautious about the police and became convinced his telephone was tapped. This lavishly illustrated book reveals how they have shaped our reading and vision of the East End. He needed to offer a big carrot, one that would get him off the hook for good. Seller Inventory think According to Boothby, Ronnie had contacted him on a number of occasions in connection with the Nigerian scheme, and when the Kray twin visited him, he agreed to the photograph being taken purely for promotional purposes. You are commenting using your Twitter account. The buildings in which the inquests into the deaths of several victims were held. Although not particularly big men, standing about five-ten and weighing under one hundred seventy pounds, they were extremely skilled fighters, and in the several hundred bar brawls, woundings, and punch-ups they were involved in, they never seemed to come off second best. -

Proceedings of the PAVESE SOCIETY 1999, Volume 10

1 Biographical Studies of Suicide, 1995, Volume 6 KURT TUCHOLSKY David Lester On the night of May 10, 1933, books of thirty four authors were burned in front of Berlin University -- books by such writers as Sigmund Freud and Bertolt Brecht. Among them were the books of Kurt Tucholsky -- satirist, song writer and cultural critic. Because of insolence and arrogance! With honor and respect for the immortal German folk spirit! Consume also, flames, the writings of Tucholsky...(Poor, 1935, p. 3). Tucholsky was the oldest of three children born to Alex Tucholsky, a Jewish businessman and banker. He was born in Berlin on January 9, 1890. A brother (Fritz) was born in 1895 and a sister (Ellen) in 1897. Tucholsky was loved by his father and grew up feeling very close to him. His mother, Doris, was a cold and rigid woman, and Tucholsky had little contact with her after he reached the age of fifteen. When Tucholsky was three, the family moved to Stettin, near the Baltic coast, and he started school in 1896. His father was made director of a bank in 1899, and so the family moved back to Berlin. Tucholsky was sent to the prestigious French Gymnasium founded in 1689 by French Huguenots expelled from France -- it was the preferred school for children of prominent Jews. However, Tucholsky left the Jewish faith early (he says in 1911) and formally became a Protestant in 1917. Tucholsky's father died suddenly in 1905, and Tucholsky's performance at school deteriorated, and he quit. However, he decided to take the school leaving certificate (Abitur) in 1909 and after passing the exam, entered Berlin University to study law. -

House of Lords Official Report

Vol. 768 Tuesday No. 108 9 February 2016 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) HOUSE OF LORDS OFFICIAL REPORT ORDER OF BUSINESS Retirement of a Member: Lord Dixon ........................................................................2111 Questions Oil and Gas: UK Continental Shelf.........................................................................2111 Housing Estates ...........................................................................................................2114 Walking and Cycling...................................................................................................2116 Daesh: Genocide..........................................................................................................2119 Transport for London Bill [HL] Motion to Consider .....................................................................................................2121 Welfare Reform and Work Bill Third Reading...............................................................................................................2121 Housing and Planning Bill Committee (1st Day) ..................................................................................................2132 Foreign and Commonwealth Office: Funding Question for Short Debate..........................................................................................2192 Housing and Planning Bill Committee (1st Day) (Continued).............................................................................2207 Grand Committee Immigration Bill Committee (5th Day)............................................................................................GC -

Essays to Commemorate the 40Th Anniversary of the 1974 Housing Act

FORESIGHT, TENACITY, VISION: Essays to Commemorate the 40th Anniversary of the 1974 Housing Act Edited by Edward Wild THE LORD BEST OBE | RICHARD BLAKEWAY | CHRISTOPHER BOYLE QC NICHOLAS BOYS SMITH | STEPHEN HOWLETT | LIZ PEACE CBE DR GRAHAM STEWART | THE RT HON SIR GEORGE YOUNG Bt CH MP Contents Foreword – The Rt Hon Sir George Young Bt CH MP ..............................................................4 Introduction – Stephen Howlett .................................................................................................6 The Act ........................................................................................................................................7 Also published by Wild ReSearch: The Essays: Strands of History: Northbank Revealed (2014) How the Housing Act 1974 changed everything ..............................................8 Clive Aslet The Lord Best OBE Standards, Freedom, Choice: Essays to Commemorate the 25th Anniversary of the 1988 Education Reform Act (2013) Forty years on ...................................................................................................... 11 Edited by Edward Wild Dr Graham Stewart Time and Tide: The History of the Harwich Haven Authority (2013) The 1970s – the decade the music stopped .................................................... 17 Dr Graham Stewart Nicholas Boys Smith Time and Chance: Preparing and Planning for a Portfolio Career (2012) ‘A town for the 21st Century’ ............................................................................ 22 Edited by -

In This Issue INTRODUCTION LTN TRIAL SCHEME TIME for CHANGE 6 14 from the CHAIRMAN 2 from the EDITOR 4

SEBRA NEWS W2 In this Issue INTRODUCTION LTN TRIAL SCHEME TIME FOR CHANGE 6 14 FROM THE CHAIRMAN 2 FROM THE EDITOR 4 SPECIAL ISSUE No 100 AUTUMN 2020 SAFETY VALVE QUEENSWAY PARADE QUESTIONS 16 SUPPORTING CYCLE LANES 17 SAVE OUR TWO PLANE TREES 18 LONDON PROPERTY DISGRACE 22 AROUND BAYSWATER MY TWO UNSUNG HEROES 43 SEBRA'S FIRST PRESS COVERAGE 50 BOB ROGERS' CORNER 62 MORE ABOUT W H SMITH 66 WCC LEADER'S SEBRA'S 50th HEATHROW WAKE UP CALL 67 26 LATEST UPDATE 29 ANNIVERSARY SEBRA - RESPECTING THE PAST 70 PHOTOS OF PEOPLE AND PARKS 74 A BAYSWATER MISCELLANY 82 COMMENTS ON OUR STREETS 84 FORTY YEARS OF DEVOTION 85 BAYSWATER'S LOST FOUNTAINS 88 BEAUTIFUL PLACES AND THINGS 90 HALLFIELD SCHOOL NEWS 102 POLICING BAYSWATER 104 CELEBRATING 100 MAGAZINES 107 SHOPPING AND RESTAURANTS 114 HEALTH AND WELLBEING SMOKE AND MIRRORS 118 HALLFIELD ESTATE RUBY - A FOUR OSTEOARTHRITIS MYTHS 120 44 THE FIRST 73 YEARS 49 LEGGED FRIEND TIPS TO BEAT THE BLOAT 121 THE ALEXANDER TECHNIQUE 122 PORCHESTER CENTRE NEWS 123 THE ROYAL PARKS THE PARKS WELCOME YOU 126 CRYSTAL PALACE VIRTUAL TOUR 127 NEWS FROM THE FRIENDS 128 SERPENTINE GALLERIES 132 POLITICAL COMMENTARY KAREN BUCK MP 134 NICKIE AIKEN MP 136 KEEPING TO THE RIGHT 138 NEW ELIZABETH THE COW KEEPING TO THE LEFT 140 57 LINE STATION 60 A REMARKABLE PUB CITY HALL NEWS WARD BUDGETS UPDATE 142 YOUR COUNCILLORS WRITE 143 PROUD TO BE SERVING OUR PROPERTY AND LICENSING MEMBERS AND THE COMMUNITY CHESTERTONS MARKET NEWS 150 KNIGHT FRANK INSIGHT 152 LICENSING SEBRALAND 154 th LETTERS AND ABOUT SEBRA SEBRA’S 50 ANNIVERSARY AND YOUR LETTERS 156 ABOUT SEBRA 159 100 EDITIONS OF OUR MAGAZINE SEBRA NEWS W2 - AUTUMN 2020 1 INTRODUCTION From the Chairman Chairman: John Zamit London.