Egypt Date: 7 June 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY in CAIRO School of Humanities And

1 THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY IN CAIRO School of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations Islamic Art and Architecture A thesis on the subject of Revival of Mamluk Architecture in the 19th & 20th centuries by Laila Kamal Marei under the supervision of Dr. Bernard O’Kane 2 Dedications and Acknowledgments I would like to dedicate this thesis for my late father; I hope I am making you proud. I am sure you would have enjoyed this field of study as much as I do. I would also like to dedicate this for my mother, whose endless support allowed me to pursue a field of study that I love. Thank you for listening to my complains and proofreads from day one. Thank you for your patience, understanding and endless love. I am forever, indebted to you. I would like to thank my family and friends whose interest in the field and questions pushed me to find out more. Aziz, my brother, thank you for your questions and criticism, they only pushed me to be better at something I love to do. Zeina, we will explore this world of architecture together some day, thank you for listening and asking questions that only pushed me forward I love you. Alya’a and the Friday morning tours, best mornings of my adult life. Iman, thank you for listening to me ranting and complaining when I thought I’d never finish, thank you for pushing me. Salma, with me every step of the way, thank you for encouraging me always. Adham abu-elenin, thank you for your time and photography. -

2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial

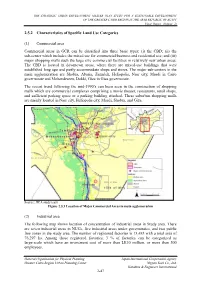

THE STRATEGIC URBAN DEVELOPMENT MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR A SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GREATER CAIRO REGION IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT Final Report (Volume 2) 2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial area Commercial areas in GCR can be classified into three basic types: (i) the CBD; (ii) the sub-center which includes the mixed use for commercial/business and residential use; and (iii) major shopping malls such the large size commercial facilities in relatively new urban areas. The CBD is located in downtown areas, where there are mixed-use buildings that were established long ago and partly accommodate shops and stores. The major sub-centers in the main agglomeration are Shobra, Abasia, Zamalek, Heliopolis, Nasr city, Maadi in Cairo governorate and Mohandeseen, Dokki, Giza in Giza governorate. The recent trend following the mid-1990’s can been seen in the construction of shopping malls which are commercial complexes comprising a movie theater, restaurants, retail shops, and sufficient parking space or a parking building attached. These suburban shopping malls are mainly located in Nasr city, Heliopolis city, Maadi, Shobra, and Giza. Source: JICA study team Figure 2.5.3 Location of Major Commercial Areas in main agglomeration (2) Industrial area The following map shows location of concentration of industrial areas in Study area. There are seven industrial areas in NUCs, five industrial areas under governorates, and two public free zones in the study area. The number of registered factories is 13,483 with a total area of 76,297 ha. Among those registered factories, 3 % of factories can be categorized as large-scale which have an investment cost of more than LE10 million, or more than 500 employees. -

Cairo International Airport

THE PINNACLE OF PRIVILEGED LIVING 4 6 7 N A Landmark Address One Zamalek stands proud on the Northern tip of Gezira Island, in the elegant and sophisticated Zamalek district. The 21-apartment tower is situated a mere walk from some of Egypt’s most attractive art, culture, dining and lifestyle destinations and just 20km from Cairo International Airport. GEZIRA ISLAND 8 9 Cairo: Enchantingly Enriching Home to One Zamalek, and enviably located Today, the city boasts a truly colourful cultural within reach of both east and west, Cairo is known scene and burgeoning economic landscape, for its millennia of culture, heritage powered by a diverse real estate market and sheer ambition. that has long been attracting attention from discerning investors with an eye for the future. From the pure genius of the pyramids to the inimitable zeal of Cairo’s residents, it is a city that is passionately weaving the threads of its rich past into a breath-taking tapestry that depicts a better tomorrow. 10 11 Life in Zamalek An inimitably eclectic, vibrant neighbourhood With a delightfully eclectic vibe, Zamalek Zamalek is also the unofficial cultural heart is one of Cairo’s most sought-after and premium of Cairo thanks to the iconic Cairo Opera residential neighbourhoods, home to embassies, House, and it was even home to legendary consulates and the city’s well-heeled. songbird, Umm Kulthum. Several magnificent palaces once dotted the district too, Known across Egypt for its abundance and have since been converted into hotels of chic cafes, buzzing nightlife, boutiques and government buildings. -

Planning Insurgencies in Ramlet Bulaq and Maspero Triangle

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Uneven City: Planning Insurgencies in Ramlet Bulaq and Maspero Triangle THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Urban and Regional Planning by Khalid Shakran Thesis Committee: Professor Walter Nicholls, Chair Professor Rodolfo Torres Professor David Smith 2016 © 2016 Khalid Shakran DEDICATION To My mother, father, sister, and the people of Ramlet Bulaq and Maspero Triangle When a conflict goes on so long, people develop a stake in its perpetuation. Norman Finkelstein “Approaching 60” The course of revolution is 360 degrees. The Last Poets “When the Revolution Comes” ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures v Acknowledgments vi Abstract of Thesis vii Chapter 1: Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of the Study ....................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Research Questions.......................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Thesis Statement .............................................................................................................................. 3 1.4 Theoretical Framework .................................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Literature Review ........................................................................................................................... -

Health Club Application

1 Cairo Marriott Hotel & Omar Khayyam Casino www.cairomarriotthotel.com 16 Saray El Gezira, Zamalek, 0020 2 27283000 HEALTH CLUB Membership Benefits FOR 1 MONTH Single 5,000 LE Couple 7,500 LE Family 9,000 LE • Unlimited access to the Health Club facilities from 7:00 am to 10:00 pm. • Complimentary use of our outdoor pool. • One complimentary personal training session with our fitness instructor. • 10% discount on massage treatments at Saray Spa. • 10% discount on retail store items. • Permanent locker is available. • 50% discount on parking during facility visits. TERMS & CONDITIONS: 1 Membership is valid for 1 month. Payment required in advance. 2 Membership is non-transferable & non-refundable. 3 Spa booking is made upon request. 4 Spa promotions are not applicable to the membership. 5 Applicants must be at least 18 years of age and above. 2 HEALTH CLUB Membership Benefits FOR 3 MONTHS Single 7,500 LE Couple 12,500 LE Family 14,500 LE • Unlimited access to the Health Club facilities from 7:00 am to 10:00 pm. • Complimentary use of our outdoor pool. • Two complimentary personal training sessions with our fitness instructor. • 10% discount on massage treatments at Saray Spa. • 10% discount on retail store items. • Permanent locker is available. • 50% discount on parking during facility visits. TERMS & CONDITIONS: 1 Membership is valid for 3 months. Payment required in advance. 2 Membership is non-transferable & non-refundable. 3 Spa booking is made upon request. 4 Spa promotions are not applicable to the membership. 5 Applicants must be at least 18 years of age and above. -

Appendix 3.2 Description of Survey Tasks

APPENDIX 3.2 DESCRIPTION OF SURVEY TASKS APPENDIX 3.2 DESCRIPTION OF SURVEY TASKS 1. Preparatory Work The candidate survey locations were visited several times to: • Select a suitable location for each survey station. • Determine the required manpower of surveyors and supervisors • Sketch the site and its surrounding features. The following precautions were considered when selecting the survey locations: • The survey site has to be on a straight part of the road to provide sufficient sight distance for the surveyor to see the coming vehicles and to secure the safety of the survey team. • The survey site should be on a level road section to avoid the increase in vehicle speed in the down-grade direction which may increase the hazards possibility against the survey team. • The survey site has to be on an illuminated section as possible to provide adequate vision to the survey team during dark periods of the survey works and maintain safety aspects to the survey team. • The survey site has to be easily accessible by optimizing the transport process of the survey team to/from each site. • A detailed sketch for each survey station site should be prepared by the site supervisors. (1) Locations of Traffic Count Survey A total of 17 traffic count stations were, originally, selected to carry out the manual classified count (MCC) for two days during 18 hours starting from 6:00 A.M. till 12:00 A.M. These count stations can be classified into two major categories. The first category (10 bridges) is represented by a screenline along the Nile River. -

Geotechnical Characterization of Subsoil Deposits at Cairo

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine International Conference on Case Histories in (1988) - Second International Conference on Geotechnical Engineering Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering 02 Jun 1988, 10:30 am - 3:00 pm Geotechnical Characterization of Subsoil Deposits at Cairo Mohamed A. El-Sohby University of Al-Azhar, Cairo, Egypt S. Ossama Mazen General Organization for Housing, Building and Planning Research, Cairo, Egypt Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icchge Part of the Geotechnical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation El-Sohby, Mohamed A. and Mazen, S. Ossama, "Geotechnical Characterization of Subsoil Deposits at Cairo" (1988). International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering. 17. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icchge/2icchge/2icchge-session2/17 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article - Conference proceedings is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Proceedings: Second International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering, June 1-5, 1988, St. Louis, Mo., Paper -

Pizza Market Egypt Overvieww

Pizza Market Overview Egypt Pillars consultancy www.PILLARS-EG.COM [email protected] Table of contents • Pizza - Italian Restaurants Classification/ Products Offered • Pizza – Italian Outlets Egypt Nation-Wide (1/3) : • Review to Pizza Local Market – Pizza Hut – Domino’s Pizza – PAPA John’s – Little Caesars – Pizza King – Peppes Pizza – Cortigiano – Roma Pizza 2 Go – Pizza Plus • Other Pizza Outlets Online Ordering / Others 2 Pizza & Italian Restaurants Table of Contents : Pizza Hut Sbarro Papa Johns Little Caesars Pizza Roma Domino’s Pizza Pizza King Peppes Pizza Cortigiano La Casetta Majesty 3 Pizza - Italian Restaurants Classification/ Products Offered Local Local Italian Restaurant Pizza Chains Local Offer/ International Local Chains * Pizza/ Oriental Pizza + Type Pizza Chains Pizza Chains + Individual Restaurants Fast Food (Feteer) Avg. Class Class A/B A+B A+B B B+C Example Pizza Hut / Little Cesares/sbarro Pizza Y Y Y Y Italian Food Y Y Y Y Oriental Pizza - - - - Fast Food - - Y Y Others Y Y Pizza Hut Thomas Lacasetta Pizza King Majesty Papa John’s Tabasco Cortigiano/ Pizza Plus Dawwar/ Example Sbarro Pizza Pomodoro/Condetti/ Cook Door Pepes Pizza Little Caesars Not Much preferred as Much Preferred for Class outing for class A as A as perceived as outlets Comments preference towards Local of the choice for Pizza Italian Chains High Average Check / higher than Average 4 Pizza – Italian Outlets Egypt Nation-Wide (1/3) : Int’l Local Other “On-line” Chains Chains* Chains & Outlets La Rosa 19 Road, Degla, Maadi shahiya.com La Casetta -

Cultural Heritage Cluster Conference Programme

Monday, May 7th Salon Vert, Cairo Marriott Hotel, Zamalek 6.00 pm Registration 6.30 pm Welcome Address – Dr. Roman Luckscheiter, Director of DAAD Office Cairo – Mr. Simon Brombeiss, Head of the Cultural Department at the Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany – H.E. Khaled El-Eneny, Minister of Antiquities at the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, tbc Panel Discussion: What is Cultural Heritage? What does it include, constitute and how is it perceived in and beyond the region? 6.45 pm Prof. Dr. Moawiyah Ibrahim Yousef, Jordan Representative to the World Heritage Committee/UNESCO Prof. Dr. Friederike Seyfried, Director of the Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection Berlin Dr. Tarek Tawfik, Director General of the Grand Egyptian Museum Project Prof. Dr. Birgit Schäbler, Director of the Orient-Institut Beirut Prof. Dr. Stephan Seidlmayer, Director of the German Archeological Institute Cairo Moderated by: Dr. Monica Hanna, Head of the Unit of Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, The Arab Academy for Science, Technology and Maritime Transport 7.30 pm Joint Networking Dinner Tuesday, May 8th Conference Hall, National Museum of Egyptian Civilization – NMEC, Fustat 9.30 am Registration and Coffee Reception 10.00 am An Overview of NMEC – Eng. Mahrous Said, General Supervisor of the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization 10.15 am COSIMENA and the Approach of Clusters of Scientific Innovation – Ms. Lilly von Stackelberg, DAAD Cairo Office Best Practice: Joint Research 10.30 am Study of Natural and Cultural Heritage Center – Prof. Nizar Abu-Jaber, German Jordanian University 1 10.50 am Projects between Germany and the MENA Region Dr. Karin Kindermann, University of Cologne 11.10 am The German Archaeological Heritage Network (ArcHerNet) and its Joint Project 'A Future for the Time after the Crisis' Dr. -

Services for UASC Partner Service Phone Number Address / Email Working Hours Health

Services for UASC Partner Service Phone Number Address / Email Working Hours Health 01129884420 6th of October, Block 8 ,48/8th 0238897129 district, second proximity Nasr City, 15 Mohammed Medical Care 0223867367 Youssef Mousa, o Mostafa Call to schedule an Caritas 0223867366 el-Nahas. appointment Al-Manteqa al-Oula Healthcare Emergency Maadi Healthcare Ard El-Lewa 24/7 01280770146 Nasr City Save The Children Psychosocial Support Hotline for adults and families: 01033316655 01033316644 For Unaccompanied & 01033316677 Separated Children and Youth: Mohandeseen - 20, Hotline for Demashk Street, Naimo Unaccompanied & Center Monday - Thursday Healthcare Separated Children 9:00 AM - 5:00 PM StARS and Youth 01033348659 For accompanied children: Tigrinya, Arabic & Downtown , 26 ,38 of July English Street (Esaaf) 01064400281 [email protected] Somali, Oromo, Amharic, Arabic & English 0227736347 Healthcare Emergency: Gender Based 01117083502 Sunday - Monday Violence Emergency (confidential) Wednesday - Maadi, No 2, Street 161 Thursday Medecins Healthcare Appointments: 9:00 AM - 6:00 PM (Pregnancy) 01012159162 Sans Frontieres 01111483267 (AWN) Clinic: General Health 01211970028 5 Michael Lotf-Allah, Reproductive Emergency for Gender All Saints Cathedral, Zamalek Health Based Violence: 01211970013 Monday - Thursday Zamalek Clinic: 9:00 AM - 4:00 PM 01203339126 For emergency Gender Refuge TB - HIV/Aids Based Violence: Egypt 01282112011 010642622 Psychosocial Helpline: Support 01100782000 Referral Email: Mental Healthcare [email protected] 24/7 -

The British Community in Occupied Cairo, 1882-1922

The British Community in Occupied Cairo, 1882-1922 By: Lanver Mak The School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Submitted for the Degree ofDoctor of Philosophy September 2001 ProQuest Number: 10731322 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731322 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 For Sarah and our parents 3 Abstract Though officially ruled by the Ottoman Empire, Egypt was under British occupation between 1882 and 1922. Most studies about the British in Egypt during this time focus on the political and administrative activities of British officials based on government documents or their memoirs and biographies. This thesis focuses on various aspects of the British community in Cairo based on sources that have been previously overlooked such as census records, certain private papers, and business, newspaper, military and missionary archives. At the outset, this discussion introduces demographic data on the British community to establish its size, residential location and context among other foreign communities and the wider Egyptian society. Then it deliberates on the occasional ambiguous boundaries that identified members of the community from non-members as well as the symbols and institutions that united the community. -

Directory of Development Organizations

EDITION 2007 VOLUME I.A / AFRICA DIRECTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS GUIDE TO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES, CIVIL SOCIETY, UNIVERSITIES, GRANTMAKERS, BANKS, MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING FIRMS Resource Guide to Development Organizations and the Internet Introduction Welcome to the directory of development organizations 2007, Volume I: Africa The directory of development organizations, listing 51.500 development organizations, has been prepared to facilitate international cooperation and knowledge sharing in development work, both among civil society organizations, research institutions, governments and the private sector. The directory aims to promote interaction and active partnerships among key development organisations in civil society, including NGOs, trade unions, faith-based organizations, indigenous peoples movements, foundations and research centres. In creating opportunities for dialogue with governments and private sector, civil society organizations are helping to amplify the voices of the poorest people in the decisions that affect their lives, improve development effectiveness and sustainability and hold governments and policymakers publicly accountable. In particular, the directory is intended to provide a comprehensive source of reference for development practitioners, researchers, donor employees, and policymakers who are committed to good governance, sustainable development and poverty reduction, through: the financial sector and microfinance,