Cairo: Mapping the Neoliberal City in Literature a Study Of: the Heron, Being Abbas El Abd and Utopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egypt Real Estate Trends 2018 in Collaboration With

know more.. Egypt Real Estate Trends 2018 In collaboration with -PB- -1- -2- -1- Know more.. Continuing on the momentum of our brand’s focus on knowledge sharing, this year we lay on your hands the most comprehensive and impactful set of data ever released in Egypt’s real estate industry. We aspire to help our clients take key investment decisions with actionable, granular, and relevant data points. The biggest challenge that faces Real Estate companies and consumers in Egypt is the lack of credible market information. Most buyers rely on anecdotal information from friends or family, and many companies launch projects without investing enough time in understanding consumer needs and the shifting demand trends. Know more.. is our brand essence. We are here to help companies and consumers gain more confidence in every real estate decision they take. -2- -1- -2- -3- Research Methodology This report is based exclusively on our primary research and our proprietary data sources. All of our research activities are quantitative and electronic. Aqarmap mainly monitors and tracks 3 types of data trends: • Demographic & Socioeconomic Consumer Trends 1 Million consumers use Aqarmap every month, and to use our service they must register their information in our database. As the consumers progress in the usage of the portal, we ask them bite-sized questions to collect demographic and socioeconomic information gradually. We also send seasonal surveys to the users to learn more about their insights on different topics and we link their responses to their profiles. Finally, we combine the users’ profiles on Aqarmap with their profiles on Facebook to build the most holistic consumer profile that exists in the market to date. -

THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY in CAIRO School of Humanities And

1 THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY IN CAIRO School of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations Islamic Art and Architecture A thesis on the subject of Revival of Mamluk Architecture in the 19th & 20th centuries by Laila Kamal Marei under the supervision of Dr. Bernard O’Kane 2 Dedications and Acknowledgments I would like to dedicate this thesis for my late father; I hope I am making you proud. I am sure you would have enjoyed this field of study as much as I do. I would also like to dedicate this for my mother, whose endless support allowed me to pursue a field of study that I love. Thank you for listening to my complains and proofreads from day one. Thank you for your patience, understanding and endless love. I am forever, indebted to you. I would like to thank my family and friends whose interest in the field and questions pushed me to find out more. Aziz, my brother, thank you for your questions and criticism, they only pushed me to be better at something I love to do. Zeina, we will explore this world of architecture together some day, thank you for listening and asking questions that only pushed me forward I love you. Alya’a and the Friday morning tours, best mornings of my adult life. Iman, thank you for listening to me ranting and complaining when I thought I’d never finish, thank you for pushing me. Salma, with me every step of the way, thank you for encouraging me always. Adham abu-elenin, thank you for your time and photography. -

Experimental Testes of Imbaba Railway Bridge

Al-Azhar University Civil Engineering Research Magazine (CERM) Vol. (41) No. (3) July, 2019 EXPERIMENTAL TESTES OF IMBABA RAILWAY BRIDGE 1 2 3 4 E.S.Youssef , H.M.Abbas , M.M.Saleh , M.A.Elewa 1 Master Student, Faculty of Engineering, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt. 2 Professor, Faculty of Engineering, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt. 3 Professor, Faculty of Engineering, CAIRO University, Giza, Egypt. 4 Assistant Professor, Faculty of Engineering, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt. ملخص البحث: تم تصميم جسور السكك الحديدية في مصر في الماضي لتعمل بشكل صحيح في ظل سيناريو تحميل محدد وظروف بيئية. لكن السيناريو الفعلي الذي يتعرض له الجسر يختلف تما ًما عما هو مصمم له. ذلك بسبب وجود الكثير من أوجه عدم اليقين في الحمولة القادمة على الهيكل وهناك دائ ًما احتمال انهيار الهيكل تحت الحمل الديناميكي. تم إجراء اختبار ثابت وديناميكي لدراسة أداء جسر سكة حديد إمبابة على نهر النيل بمحافظة القاهرة في ظل اختبار ثابت وديناميكي ، وكذلك ، استخراج المعامﻻت المشروطه )النمط ، التخميد ، والتردد الطبيعي(. ABSTRACT : The Railway Bridges in Egypt are designed at the past to perform properly under a definite loading scenario and environmental conditions. But the actual scenario to which a bridge is exposed is quite different than it is designed for. It is because there are lot of uncertainties in load coming over the structure and there is always a possibility for collapse of the structure under dynamic load. The static and dynamic test was carried out to study the performance of the Imbaba Railway Bridge over Nile River in Cairo governorate under ststic and dynamic test, also, extract modal parameter (mode shape, damping, and natural frequency). -

Shallow Geophysical Techniques to Investigate the Groundwater Table at the Giza 2 Pyramids Area, Giza, Egypt 3 4 S

1 Shallow Geophysical Techniques to Investigate the Groundwater Table at the Giza 2 Pyramids Area, Giza, Egypt 3 4 S. M. Sharafeldin1,3, K. S. Essa1, M. A. S. Youssef2*, H. Karsli3, Z. E. Diab1, and N. Sayil3 5 1Geophysics Department, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Giza, P.O.12613, Egypt 6 2Nuclear Materials Authority, P.O. Box 530, Maadi, Cairo, Egypt 7 3Geophysical Engineering Department, KTU, Turkey 8 *[email protected] 9 ABSTRACT 10 The near surface groundwater aquifer that threatened the Great Giza Pyramids of Egypt, 11 was investigated using integrated geophysical surveys. Ten Electrical Resistivity Imaging, 26 12 Shallow Seismic Refraction and 19 Ground Penetrating Radar surveys were conducted in the 13 Giza Pyramids Plateau. Collected data of each method evaluated by the state- of- the art 14 processing and modeling techniques. A three-layer model depicts the subsurface layers and 15 better delineates the groundwater aquifer and water table elevation. The aquifer layer resistivity 16 and seismic velocity vary between 40-80 Ωm and 1500-1800 m/s. The average water table 17 elevation is about +15 meters which is safe for Sphinx Statue, and still subjected to potential 18 hazards from Nazlet Elsamman Suburban where a water table elevation attains 17 m. Shallower 19 water table in Valley Temple and Tomb of Queen Khentkawes of low topographic relief 20 represent a sever hazards. It can be concluded that perched ground water table detected in 21 elevated topography to the west and southwest might be due to runoff and capillary seepage. 22 23 Keywords: Giza Pyramids, Groundwater, Electrical Resistivity, Seismic refraction, GPR. -

Exposure Assessment and the Risk Associated with Trihalomethane Compounds in Drinking Water, Cairo

ntal & A me na n ly o t ir ic v a Souaya et al., J Environ Anal Toxicol 2014, 5:1 n l T E o Journal of f x o i l DOI: 10.4172/2161-0525.1000243 c o a n l o r g u y o J Environmental & Analytical Toxicology ISSN: 2161-0525 ResearchResearch Article Article OpenOpen Access Access Exposure Assessment and the Risk Associated with Trihalomethane Compounds in Drinking Water, Cairo – Egypt Eglal R Souaya1, Ali M Abdullah2*, Gouda A RMaatook3 and Mahmoud A khabeer2 1Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University, Khalifa El-Maamon Street, Cairo, 11566, Egypt 2Holding Company for water and wastewater, IGSR, Alexandria -1125, Egypt 3Central Laboratory of Residue Analysis of Pesticides and Heavy Metals in Foods, Agricultural Research Centre, Ministry of Agriculture and Land Reclamation, Egypt Abstract The main objectives of the study to measure the concentrations of trihalomethanes (THMs) in drinking water of Cairo, Egypt, and their associated risks. Two hundred houses were visited and samples were collected from consumer taps water. Risks estimates based on exposures were projected by employing deterministic and probabilistic approaches. The THMs species (dibromochloromethane, bromoform, chloroform, and bromodichloromethane) ranged from not detected to 76.8 μg/lit. Non-carcinogenic risks induced by ingestion of THMs were exceed the tolerable level (10-6). Data obtained in this research demonstrate that exposure to drinking water contaminants and associated risks were higher than the acceptable level. Keywords: Drinking water; Risk; Trihalomethanes; Cairo routes. In response to the increasing public concern on the pollution of the water supply, this study aims to estimate the THM exposure, Introduction lifetime CR caused by these different routes due to the use of tap water Chlorination, the most commonly used method to disinfect tap in the Cairo, Egypt. -

Mints – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY

No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 USD1.00 = EGP5.96 USD1.00 = JPY77.91 (Exchange rate of January 2012) MiNTS: Misr National Transport Study Technical Report 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Item Page CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 BACKGROUND...................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 THE MINTS FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................1-1 1.2.1 Study Scope and Objectives .........................................................................................................1-1 -

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

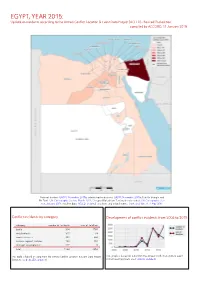

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

Flood-Induced Scour in the Nile by Modified Operation of High Aswan Dam

Conference Paper, Published Version Sloff, C. J.; El-Desouky, I. A. Flood-induced scour in the Nile by modified operation of High Aswan Dam Verfügbar unter/Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11970/100075 Vorgeschlagene Zitierweise/Suggested citation: Sloff, C. J.; El-Desouky, I. A. (2006): Flood-induced scour in the Nile by modified operation of High Aswan Dam. In: Verheij, H.J.; Hoffmans, Gijs J. (Hg.): Proceedings 3rd International Conference on Scour and Erosion (ICSE-3). November 1-3, 2006, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Gouda (NL): CURNET. S. 614-621. Standardnutzungsbedingungen/Terms of Use: Die Dokumente in HENRY stehen unter der Creative Commons Lizenz CC BY 4.0, sofern keine abweichenden Nutzungsbedingungen getroffen wurden. Damit ist sowohl die kommerzielle Nutzung als auch das Teilen, die Weiterbearbeitung und Speicherung erlaubt. Das Verwenden und das Bearbeiten stehen unter der Bedingung der Namensnennung. Im Einzelfall kann eine restriktivere Lizenz gelten; dann gelten abweichend von den obigen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. Documents in HENRY are made available under the Creative Commons License CC BY 4.0, if no other license is applicable. Under CC BY 4.0 commercial use and sharing, remixing, transforming, and building upon the material of the work is permitted. In some cases a different, more restrictive license may apply; if applicable the terms of the restrictive license will be binding. Flood-induced scour in the Nile by modified operation of High Aswan Dam C.J. Sloff* and I.A. El-Desouky ** * WL | Delft Hydraulics and Delft University of Technology, Delft, Netherlands ** Hydraulics Research Institute (HRI), Delta Barrage, Cairo, Egypt Due to climate-change it is anticipated that the hydrological m. -

2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial

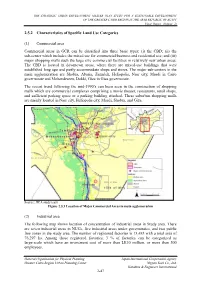

THE STRATEGIC URBAN DEVELOPMENT MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR A SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GREATER CAIRO REGION IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT Final Report (Volume 2) 2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial area Commercial areas in GCR can be classified into three basic types: (i) the CBD; (ii) the sub-center which includes the mixed use for commercial/business and residential use; and (iii) major shopping malls such the large size commercial facilities in relatively new urban areas. The CBD is located in downtown areas, where there are mixed-use buildings that were established long ago and partly accommodate shops and stores. The major sub-centers in the main agglomeration are Shobra, Abasia, Zamalek, Heliopolis, Nasr city, Maadi in Cairo governorate and Mohandeseen, Dokki, Giza in Giza governorate. The recent trend following the mid-1990’s can been seen in the construction of shopping malls which are commercial complexes comprising a movie theater, restaurants, retail shops, and sufficient parking space or a parking building attached. These suburban shopping malls are mainly located in Nasr city, Heliopolis city, Maadi, Shobra, and Giza. Source: JICA study team Figure 2.5.3 Location of Major Commercial Areas in main agglomeration (2) Industrial area The following map shows location of concentration of industrial areas in Study area. There are seven industrial areas in NUCs, five industrial areas under governorates, and two public free zones in the study area. The number of registered factories is 13,483 with a total area of 76,297 ha. Among those registered factories, 3 % of factories can be categorized as large-scale which have an investment cost of more than LE10 million, or more than 500 employees. -

Cairo International Airport

THE PINNACLE OF PRIVILEGED LIVING 4 6 7 N A Landmark Address One Zamalek stands proud on the Northern tip of Gezira Island, in the elegant and sophisticated Zamalek district. The 21-apartment tower is situated a mere walk from some of Egypt’s most attractive art, culture, dining and lifestyle destinations and just 20km from Cairo International Airport. GEZIRA ISLAND 8 9 Cairo: Enchantingly Enriching Home to One Zamalek, and enviably located Today, the city boasts a truly colourful cultural within reach of both east and west, Cairo is known scene and burgeoning economic landscape, for its millennia of culture, heritage powered by a diverse real estate market and sheer ambition. that has long been attracting attention from discerning investors with an eye for the future. From the pure genius of the pyramids to the inimitable zeal of Cairo’s residents, it is a city that is passionately weaving the threads of its rich past into a breath-taking tapestry that depicts a better tomorrow. 10 11 Life in Zamalek An inimitably eclectic, vibrant neighbourhood With a delightfully eclectic vibe, Zamalek Zamalek is also the unofficial cultural heart is one of Cairo’s most sought-after and premium of Cairo thanks to the iconic Cairo Opera residential neighbourhoods, home to embassies, House, and it was even home to legendary consulates and the city’s well-heeled. songbird, Umm Kulthum. Several magnificent palaces once dotted the district too, Known across Egypt for its abundance and have since been converted into hotels of chic cafes, buzzing nightlife, boutiques and government buildings. -

GEORGIA – EGYPT Economic Development Connection

GEORGIA – EGYPT Economic Development Connection Government & Commerce partnership agreements with Egyptian schools such as Ain Shams University, Alexandria The Embassy of the Arab Republic of Egypt, University, Helwan University and the Egyptian located in Washington, D.C., has jurisdiction over University Sports Federation. These partnerships the states of Georgia, Delaware, Florida, focus on student and faculty exchanges as well Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia as joint research efforts especially for and West Virginia. Mr. Mohamed Tawfik has international grants. served as Egypt’s Ambassador to the United Georgia State University has a cooperation States since September 2012. agreement with Egypt’s Cairo University to help The Atlanta Civic Center, in partnership with build degree programs in business and nursing Emory University’s Michael C. Carlos Museum, and facilitate collaboration in curriculum hosted the King Tut exhibition in 2008. It innovation, teaching, research and service. attracted hundreds of visitors to Georgia and had The University System of Georgia offers four a very positive economic impact. The Michael C. study abroad programs to Egypt, including a Carlos Museum has a permanent collection of history program traveling to Cairo, Alexandria ancient Egyptian art. and Luxor and an Arabic language program in In 2009 the Egypt development group, Hands Cairo. Along the Nile, hosted a dialogue event on the role of the media in relations between the Nile Trade Relationship region and the United States. EXPORTS: In 2012, Georgia exports to Egypt The Atlanta chapter of the Egypt Cancer totaled $170 million. Egypt is currently the 40th Network hosted a gala in May of 2012 at the Fox largest export market for Georgia. -

Information for Asylum-Seekers and Refugees in Egypt

UNHCR The UN Refugee Agency Information For Asylum-Seekers and Refugees in Egypt United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Regional Representation in Egypt Cairo, April 2013 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 4 PART ONE: UNHCR MANDATE AND ITS ROLE IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT 5 1.1 UNHCR Mandate 5 1.2 UNHCR Role in the Arab Republic of Egypt 7 PART TWO: RECEPTION AND GENERAL OFFICE PROCEDURES 11 2.1 Reception 11 2.2 General Office Procedures 13 2.3 Code of Conduct 18 PART THREE: REGISTRATION AND DOCUMENTATION FOR REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS 22 3.1 Registration Process 22 3.2 Documentation-Process 29 PART FOUR: REFUGEE STATUS DETERMINATION PROCESS 42 4.1 Refugee Status Determination (RSD interview) 42 4.2 Legal Aid / Representation 45 4.3 Notification of RSD decisions 46 2 4.4 Appeal process 50 4.5 Cancellation and cessation of refugee status 54 4.6 Re-opening requests 56 4.7 Family unity 58 PART FIVE: LEGAL PROTECTION 64 PART SIX: ACCESS TO ASYLUM RIGHTS 66 6.1 Access to Health Care 66 6.2 Access to Education 73 6.3 Psycho-Social support at community level 79 6.4 Access to community based services 81 PART SEVEN: MEANS OF LIVELIHOOD 83 7.1 Means of live lihood 83 7.2 Vocational training 85 PART EIGHT: FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE 87 PART NINE: DURABLE SOLUTIONS 90 9.1 Voluntary Repatriation 90 9.1.1 Return to South Sudan 94 9.1.2 Return to the Sudan 97 9.1.3 Return to Iraq 98 9.2 Local Integration 101 9.3 Resettlement 102 PART TEN: UNHCR CAIRO COMPLAINTS PROCEDURES 109 PART ELEVEN: USEFUL CONTACTS 113 3 INTRODUCTION The purpose of this information booklet is to provide an overview of the mandate of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the relevant criteria and procedures that are implemented by UNHCR in Egypt.