A-A- 364, L =A3?Apol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fonds National REDD+ De La RDC Promotion Des Systèmes Agro Forestiers À Petite Échelle

Fonds National REDD+ de la RDC Promotion des systèmes agro forestiers à petite échelle Programme Intégré REDD+ Kwilu Organisation(s) Participante(s) Objectif Spécifique du Fonds Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale La séquestration du carbone et l’évitement de la (JICA) déforestation á travers la promotion de l’agroforesterie et l’amélioration de conditions de vie des populations Directeur de Programme : Chef(s) de file gouvernemental (le cas échéant) : Nom : M. Toshimichi AOKI Téléphone : (243)81-556-3530 E-mail : [email protected] Titre du Programme REDD+ : Numéro du Programme : Programme intégré REDD+ dans la province de AMI n°15 Kwilu - la promotion de l’agroforesterie dans les savanes pour la séquestration de carbone, l’atténuation de la déforestation et l’amélioration de la vie de la population locale Coûts du Programme : Lieu du Programme : Fonds : 3 999 607 USD Province : Kwilu Autre (JICA): 3 389 287 USD Territoires: à préciser TOTAL (USD) : 7 388 894 USD Secteurs: à remplacer par les axes routiers Organisations Participantes : Durée du Programme : 1. JICA Durée totale (en mois) : 57 mois 2. Ministère provincial de l’Environnement et Date de commencement prévue : 15/04/18 Développement Durable (MEDD) 3. Ministère provincial de l’Agriculture (MINAGRI) 4. ONG locales (à préciser) i TABLE DES MATIÈRES 1. RESUME OPERATIONNEL DETAILLÉ ................................................................................................................... 1 2. LOCALISATION DU PROJET ................................................................................................................................ -

Document Annexe 4 Résultats Des Études Sur Les Moteurs De La Déforestation

Projet de Renforcement du Système National de Monitoring des Ressources Forestières pour la Promotion de la Gestion Durable des Forêts et REDD+ en République Démocratique du Congo Rapport Final Document annexe 4 Résultats des études sur les moteurs de la déforestation Document annexe - 67 Projet de Renforcement du Système National de Monitoring des Ressources Forestières pour la Promotion de la Gestion Durable des Forêts et REDD+ en République Démocratique du Congo Rapport Final Document annexe - 68 Projet de Renforcement du Système National de Monitoring des Ressources Forestières pour la Promotion de la Gestion Durable des Forêts et REDD+ en République Démocratique du Congo Rapport Final 1 Contexte et objectif Dans le cadre du projet JICA, la carte de couverture forestière de l’année 2010 de l'ancienne province du Bandundu (provinces actuelles de Kwilu, Kwango et Mai-Ndombe) a été préparée en utilisant les images satellitaires de ALOS et SPOT. L’établissement des cartes de quatre moments, 1995, 2000, 2010 et 2014, est fait à travers la méthodologie de détection de changement de forêt en utilisant comme une carte de référence la carte mentionnée ci-dessus avec la utilisation des images de Landsat. Le NERF est établi en calculant les données d’activités (DA) au moyen des quatre moments de carte par la méthode mur à mur. Dans l’endroit où on a constaté la perte de la forêt au moyen de la télédétection pendant la période déterminée, au moyen d’interview à la population locale et d’étude sur terrain, cette étude des moteurs (causes) de la déforestation et de la dégradation des forêts vise à (1) déterminer les moteurs (causes) de la perte et le gain des forêts et (2) de connaître les activités sociales et économiques menées par la population locale qui cause la déforestation et la dégradation de la forêt et d’analyser les relations entre la population locale et les forêts. -

In Search of Peace: an Autopsy of the Political Dimensions of Violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo

IN SEARCH OF PEACE: AN AUTOPSY OF THE POLITICAL DIMENSIONS OF VIOLENCE IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO By AARON ZACHARIAH HALE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Aaron Zachariah Hale 2 To all the Congolese who helped me understand life’s difficult challenges, and to Fredline M’Cormack-Hale for your support and patience during this endeavor 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I was initially skeptical about attending The University of Florida (UF) in 2002 for a number of reasons, but attending UF has been one of the most memorable times of my life. I have been so fortunate to be given the opportunity to study African Politics in the Department of Political Science in a cozy little town like Gainesville. For students interested in Africa, UF’s Center for African Studies (CAS) has been such a fantastic resource and meeting place for all things African. Dr. Leonardo Villalón took over the management of CAS the same year and has led and expanded the CAS to reach beyond its traditional suit of Eastern and Southern African studies to now encompass much of the sub-region of West Africa. The CAS has grown leaps and bounds in recent years with recent faculty hires from many African and European countries to right here in the United States. In addition to a strong and committed body of faculty, I have seen in my stay of seven years the population of graduate and undergraduate students with an interest in Africa only swell, which bodes well for the upcoming generation of new Africanists. -

Urban Population Map Gis Unit, Monuc 12°E 14°E 16°E 18°E 20°E 22°E 24°E 26°E 28°E 30°E

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO Map No- KINSUB1614 AFRICA URBAN POPULATION MAP GIS UNIT, MONUC 12°E 14°E 16°E 18°E 20°E 22°E 24°E 26°E 28°E 30°E CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SUDAN CAMEROON Mobayi-Mbongo Zongo Bosobolo Ango N Gbadolite N ° ° 4 Yakoma 4 Niangara Libenge Bondo Dungu Gemena Mombombo Bambesa Poko Isiro Aketi Bokungu Buta Watsa Aru r e v i Kungu R i g Dimba n a b Binga U Lisala Bumba Mahagi Wamba Nioka N N ° C ° 2 o 2 ng o Djugu R i v Lake Albert Bongandanga er Irumu Bomongo Bunia Basankusu Basoko Bafwasende Yahuma Kituku Yangambi Bolomba K ii s a n g a n ii Beni Befale Lubero UGANDA Katwa N M b a n d a k a N ° ° 0 0 Butembo Ingende Ubundu Lake Edward Kayna GABON Bikoro Opala Lubutu Kanyabayonga CONGO Isangi Boende Kirumba Lukolela Rutshuru Ikela Masisi Punia Kiri WalikaleKairenge Monkoto G o m a Inongo S S ° Lake Kivu ° 2 RWANDA 2 Bolobo Lomela Kamisuku Shabunda B u k a v u Walungu Kutu Mushie B a n d u n d u Kamituga Ilebo K ii n d u Oshwe Dekese Lodja BURUNDI Kas Katako-Kombe ai R Uvira iver Lokila Bagata Mangai S Kibombo S ° ° 4 4 K ii n s h a s a Dibaya-Lubwe Budja Fizi Bulungu Kasongo Kasangulu Masi-Manimba Luhatahata Tshela Lubefu Kenge Mweka Kabambare TANZANIA Idiofa Lusambo Mbanza-Ngungu Inkisi ANGOLA Seke-Banza Luebo Lukula Kinzau-Vuete Lubao Kongolo Kikwit Demba Inga Kimpese Boma Popokabaka Gungu M b u j i - M a y i Songololo M b u j i - M a y i Nyunzu S S ° M a tt a d ii ° 6 K a n a n g a 6 K a n a n g a Tshilenge Kabinda Kabalo Muanda Feshi Miabi Kalemie Kazumba Dibaya Katanda Kasongo-Lunda Tshimbulu Lake Tanganyika Tshikapa -

REPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO Justice-Paix-Travail

REPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO Justice-Paix-Travail Public Disclosure Authorized Ministère de l’Urbanisme et Habitat PROJET DE DEVELOPPEMENT URBAIN «PDU» Public Disclosure Authorized Secrétariat Général à l’Urbanisme et Habitat Direction d’Etudes et Planification Secrétariat Permanent Public Disclosure Authorized ETUDE D’IMPACT ENVIRONNEMENTAL ET SOCIAL DES TRAVAUX DE RÉHABILITATION ET DE MODERNISATION ETUDE D’IMPACT ENVIRONNEMENTAL ET SOCIAL DES BÂTIMENTS SCOLAIRES DES TROIS ÉCOLES DANS SIMPLIFIEELA VILLE DE KIKWIT : EP 2 KANZOMBI ; EP 2 VUKANA; INSTITUT KANGULUMBA DANS LA PROVINCE DE KWILU Public Disclosure Authorized JUIN 2019 2 LISTE DES ABREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................... 6 LISTE DES TABLEAUX ................................................................................................................ 7 LISTE DES PHOTOS .................................................................................................................... 8 Résumé non technique ................................................................................................................ 9 I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 29 1.1. Contexte et Justification .................................................................................................................. 29 1.1.1. Composantes du Projet .................................................................................................... -

Ipc 17Eme Cycle.Pdf (French (Français))

République Démocratique Cadre Intégré de Classification de la Sécurité Alimentaire du Congo Analyse de la situation courante IPC Aiguë 17ème cycle Juillet 2019 15°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 30°0'0"E Nigeria Chad Central African Rep South Sudan N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 5 5 Cameroon Bosobolo Ango Gbadolite Zongo Bondo Mobayi-Mbongo Dungu Libenge Bondo Aba Yakoma Dingila Niangara Dungu Gemena Businga Faradje Ingbokolo Gemena Aketi Bambesa Poko Watsa AruAriwara Buta Buta Aru Aketi RunguIsiro Watsa Bumba Kungu Budjala Lisala Mahagi Lisala Bumba WambaWamba Djugu Basoko Mongwalu Bongandanga Banalia Bunia BomongoMakanza Mambasa Basankusu Basoko Irumu Basankusu Djolu Yahuma Yangambi Bafwasende Oïcha Befale Isangi Kisangani Bolomba Beni-Ville " Beni Uganda " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° LuberoButembo ° 0 Mbandaka 0 Gabon Boende Ingende Boende Ubundu Rep Congo Bikoro Opala LubutuLubutu Bokungu Walikale Rutshuru Ikela Rutshuru Lukolela Punia Masisi Kiri Monkoto Nyiragongo Inongo Punia Inongo Kalehe Idjwi BoloboYumbi Lomela Kabare Rwanda Mushie Kailo Kalima Shabunda Bolobo Nioki Shabunda Walungu Dem Rep Congo Kutu Katako-Kombe Kindu Kamituga Oshwe Pangi Uvira Burundi Bandundu Dekese Mwenga Lodja Uvira Kwamouth Kole Bagata Tshumbe Lodja Mangai Kibombo Namoya Baraka Bena-Dibele Kinshasa Ilebo Kasongo Kasangulu Bulungu Mweka Kabambare Fizi Idiofa Kasongo S Lubefu S " Luozi Kasangulu Bulungu Lusambo " 0 0 ' Kenge ' 0 Tshela 0 ° Kikwit Idiofa Ilebo Lusambo ° 5 Masi-Manimba Dimbelenge Tanzania 5 Mbanza-Ngungu Lukula MadimbaKimvula Kenge Luebo Demba Lubao KongoloKongolo SongololoBangu -

Democratic Republic of Congo Media and Telecoms Landscape Guide December 2012

1 Democratic Republic of Congo Media and telecoms landscape guide December 2012 2 Index Page Introduction...............................................................................................3 Media overview.......................................................................................14 Media groups...........................................................................................24 Radio overview........................................................................................27 Radio stations..........……………..……….................................................35 List of community and religious radio stations.......…………………….....66 Television overview.................................................................................78 Television stations………………………………………………………......83 Print overview........................................................................................110 Newspapers…………………………………………………………......…..112 News agencies.......................................................................................117 Online media……...................................................................................119 Traditional and informal channels of communication.............................123 Media resources.....................................................................................136 Telecoms companies..............................................................................141 Introduction 3 The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has been plagued by conflict, corruption -

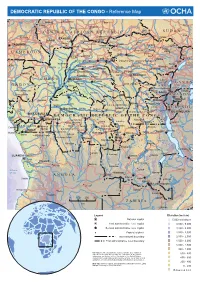

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO - Reference Map

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO - Reference Map Bozoum Bossangoa Bria Bouar Bor W Bambari h Sibut i t e Obo S U D A N N i C E N T R A L A F R I C A N R E P U B L I C l Juba e Bertoua Bangassou Yambio BANGUI Berbérati Bosobolo Mobaye Ango Mbaïki Gbadolite YAOUNDÉ Yakoma Bondo Niangara Faradje Nola Libenge Uele Dungu Gemena Rungu Bambesa Watsa C A M E R O O N Poko Aketi Buta Aru Kungu Budjala Isiro Lisala Bumba Wamba Mahagi EQUATEUR PROVINCE ORIENTALE Djugu Impfondo Lake Oyem Bunia Albert Ouesso Makanza Basoko Banalia Mambasa Irumu Bomongo Bongandanga Bafwasende Basankusu Djolu Yahuma Yangambi Makokou Isangi Kisangani Bolomba Befale C O N G O Mbandaka Lubero Boende NORD Owando Ingende Tshuapa Opala Ubundu U G A N D A G A B O N Ewo Lualaba Lubutu Lake Bikoro Bokungu KIVU Lukolela Lomani Edward Luilaka Rutshuru Koulamoutou Walikale Kiri Ikela Goma Bukoba Congo Monkoto Punia Franceville Inongo R WA N D A Lomela Djambala Bolobo Lomela Bukavu KIGALI Kutu Kindu Shabunda Mushie KASAI-ORIENTAL SUD Bandundu Oshwe Katako Kombe B U R U N D I Sibiti Dekese Kole Pangi KIVU Bagata Kasai Lodja MANIEMA Uvira BUJUMBURA BRAZZAVILLE D E M O C R A T I C R E P U B L I C O F T H E C O N G O Pointe- KINSHASA Bulungu Kasongo Fizi Noire Lubefu Luozi Masi Manimba Mweka Kabambare Kigoma BAS-CONGO Kenge Kikwit Luebo Lusambo Cabinda Mbanza Idiofa KASAI Lubao Kongolo Matadi Ngungu BANDUNDU OCCIDENTAL Nyunzu Kalemie Popokabaka Gungu Kabeya Kabalo Muanda Kwango Kananga Kabinda Boma M'Banza Congo Feshi Kasongo Lunda Tshikapa Mbuji Lake Tshimbulu Mayi Tanganyika Kahemba -

Ccoperative Agreement on Human Settlements And

CCOPERATIVE AGREEMENT ON HUMAN SETTLEMENTS AND NATURAL RESOURCE SYSTEMS ANALYSIS DOCUMENTS REVIEW AREA FOOD AND MARKETI C; DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Zaire Richard Downs Cyril K. Daddich Clark University Institute for Development Anthropology International Development Program Suite 302. P.O. Box 818 950 Main Street 99 Collier Street Wo-cester, MA 01610 Binghamton. NY 13902 DOCUMENTS REVIEW AREIA FOOD AND MARKETING DEVELOPMlENT PROJECT, ZAIRE Richard Downs Cyril K. Daddieh Cooperative Agreement in Human Settlement and Natural Resource Systems Analysis October, 1985 PREFACE This report presents reviews of materials available in Kinshasa relevant to AID Project No. 660-0102 on Agricultural Production and Marketing in the region of Bandundu. The purpose of the reviews by Richard Downs (anthropolo gist, University of New Hampshire, and Cyril Daddieh (economist, University of Iowa) was to inventory available information so as to support a possible future project in Bandundu Region focusing upon rural-urban dynamics. In earlier dis cussions with USAID/Kinshasa staff, the notion was conveyed that, in the con text of Project 102, what is now needed is a better understanding of the rural urban relationships and the dynamics among the four large towns (as well as with the largest city, Kikwit) and between the towns and the agricultural areas of tiie region. It was felt that before appropriate interventions are put in place, studies of their impacts upon the rural-urban dynamic would greatly strengthen any benefits of the investments. Professors Downs and Daddieh spent one month in Kinshasa reviewing docu ments and visiting several rural villages. In their reports, they summarize the informational content of the material, and they offer their impressions of the context of rural society within which a possible development program based upon rural-urban issues might be undertaken. -

Book 20120901.Indd

Editors: Rod Holling-Janzen, Nancy J. Myers, and Jim Bertsche Authors: Vincent Ndandula, Jean Felix Chimbalanga, Jackson Beleji, Jim Bertsche, and Charity Eidse Schellenberg Copyright 2012 by Institute of Mennonite Studies RépubliqueCopublished with Institute Démocratique for the Study of Global Anabaptism du Congo (Democratic Republic of Congo) CHAD CENTRAL AFRICAN SOUTH SUDAN REPUBLIC CAMEROON Banjwadi Kisangani UGANDA REPUBLIC Mbandaka OF CONGO GABON Goma Bukavu RWANDA Bandundu BURUNDI Vanga Pungu Ilebo (Port-Francqui) Mweka Kinshasa Kikwit Idiofa Ndjoko Punda (Charlesville) Cabinda (ANGOLA) (Léopoldville) Luebo Mutoto TANZANIA Kananga (Luluabourg) Feshi Tshikapa Mbuji Mayi (Bakwanga) Gandajika Kahemba Lubondai Mwene Ditu ANGOLA Kolwezi Lubumbashi (Elisabethville) ZAMBIA MOZAMBIQUE 02100 00400 ZIMBABWE NAMIBIA Kilometers Map by GMI Editors: Rod Holling-Janzen, Nancy J. Myers, and Jim Bertsche Authors: Vincent Ndandula, Jean Felix Chimbalanga, Jackson Beleji, Jim Bertsche, and Charity Eidse Schellenberg Copyright 2012 by Institute of Mennonite Studies Copublished with Institute for the Study of Global Anabaptism Carte régionale des dé (The region of Menn GABON BANDUNDU REPUBLIC OF CONGO Kasai Kwilu Pung Kikwit Cabinda M (ANGOLA) Kafumba Nzaji Mukedi Gungu N Kandale Shakenge Kahemba ANGOLA Kamayala Kajiji Editors: Rod Holling-Janzen, Nancy J. Myers, and Jim Bertsche Authors: Vincent Ndandula, Jean Felix Chimbalanga, Jackson Beleji, Jim Bertsche, and Charity Eidse Schellenberg Copyright 2012 by Institute of Mennonite Studies Copublished with Institute for the Study of Global Anabaptism ébuts mennonites en RDC nonite origins in the DRC) KASAI i OCCIDENTAL Basonga gu KASAI ORIENTAL Madimbi Banga Ndjoko Punda Karuru Lubu-Kakese Kananga Nioka Kakese Nyanga Mbuji Mayi Kalonda Tshikapa Lulua Kalamba Mwene Ditu Loange Mutena Kasai 0150 00200 Kilometers Map Editors: Rod Holling-Janzen, Nancy J. -

Water Issues in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Challenges and Opportunities Technical Report

Water Issues in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Challenges and Opportunities Technical Report United Nations Environment Programme First published in January 2011 by the United Nations Environment Programme © 2011, United Nations Environment Programme This report has also been published in French, entitled: Problématique de l’Eau en République Démocratique du Congo: Défis et Opportunités. United Nations Environment Programme P.O. Box 30552, Nairobi, KENYA Tel: +254 (0)20 762 1234 Fax: +254 (0)20 762 3927 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.unep.org This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from UNEP. The contents of this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of UNEP, or contributory organizations. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP or contributory organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Cover Image: © UNEP – Public standpost managed by the community-based water user association of Lubilanji in Mbuji-Mayi, Kasai Orientale Author: Hassan Partow Photos: © UNEP, Hassan Partow UNEP promotes Design and layout: Matija Potocnik environmentally sound practices globally and in its own activities. This publication is printed on recycled paper using eco-friendly practices. -

Ebola Mission Report Kikwit Zaire 16/5=1/7 1995

EBOLA MISSION REPORT KIKWIT ZAIRE 16/5=1/7 1995 Rapporten har utarbetats av Håkan Eriksson Anders Tegnell Bo Niklasson 1995 Statens Räddningsverk, Karlstad Räddningstjanstavdelningen Beställningsnr P22-106195 1995 års utgåva Utgivare Uppdragsgivare Statens räddningsverk Statens räddningsverk Författare Hakan Eriksson Anders Tegnell Bo Niklasson Summary 715 A first request for WHO assistance was received from Zaire on Sunday 7 May. 915 The team composes of experts from WHO, COC in Atlanta, the Pasteur Institute in Paris and the Natio- nal Institute for Virology in Johannesburg. Their mission is to assist in comfirming the diagnosis, advising local health officials on patient care and management and assist in efforts to contain the outbreak. 1115 WHO confirmed today that the Ebola vims is implicated in the outbreak of haemorrhagic fever in Zaire. MSF is playing an important role in setting up case facilities for patients. 1U5 Health workers are touring Kikwit with megaghones advising people to the General Hospital (Kikwit 1) if they had symptoms of disease. The bodies of the epidernic's victims are regulary picked up by the Red Cross of Zaire which is also taken care of their burial. 1415 A request for at least two French speaking logisticians, for an initial period of 15 days. Logistical sup- port, particulary ensuring communications and transportation. The Swedish National Board of Health and welfare and the Swedish Rescue Services Agency decide to send three consultants assigned to WHO. 1515 WHO team members begin to trace contacts of those who have died or become il1 as part of a surveillance operation. The Swedish team 1 leaves Sweden for Kikwit, Zaire via Geneva.