Allergy to Tree Nuts and Edible Seeds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sesame Ginger Salmon Sesame Ginger Salmon

WHAT YOU NEED WHAT YOU NEED TO DO SESAME GINGER SALMON SESAME GINGER SALMON WHAT YOU NEED WHAT YOU NEED TO DO • 4 (5oz./140g each) salmon In a medium bowl, whisk together all the marinade Serves: 4 Prep: 5 mins fillets ingredients. Cook: 20 mins For the marinade: Place the salmon in a large bowl, and cover with the • 2 tbsp. soy sauce marinade. Leave to rest for at least 30 minutes to • 2 tbsp. rice vinegar overnight. • 2 tbsp. sesame oil Nutrition per • 2 tbsp. honey Preheat oven to 400F (200C). Place the salmon fillets serving: • 2 cloves garlic, minced with the marinade onto a prepared baking dish and bake 424 kcal • 1 tbsp. ginger, grated for about 20 minutes, until salmon is cooked through. 25g Fats • 1 tbsp. sesame seeds 17g Carbs • 4 green onions, minced (or Serve salmon immediately with Egg Fried Cauliflower 39g Protein finely sliced) Rice. DF LC MP HP Q WHAT YOU NEED WHAT YOU NEED TO DO EGG FRIED CAULIFLOWER RICE EGG FRIED CAULIFLOWER RICE WHAT YOU NEEDNED WHAT YOU NEED TO DO • 1 medium cauliflower Grate cauliflower using the largest side of a grater or just by Serves: 4 Prep: 10 mins • 2 tbsp. sesame oil pulsing it in a food processor, until it looks like rice grains. Cook: 10 mins • 1 carrot, diced • 2 garlic cloves, minced Heat 1 tbsp. of sesame oil in a large skillet over medium-low • 2 celery sticks, chopped heat. Add the carrot and garlic and stir fry for about 5 • 2 eggs, beaten minutes. -

Tree Nut Allergy

TREE NUT ALLERGY Tree nut allergy is one of the most common food allergies in children and adults, and can cause a severe, potentially fatal allergic reaction (anaphylaxis). Tree nuts include, but are not limited to: almond, Brazil nut, cashew, hazelnut, macadamia, pecan, pine nut, pistachio and walnut. These are not to be confused or grouped together with peanut, which is a legume, or seeds, such as sunflower or sesame. What is a food allergy? test results with the information given Severe Symptoms or Anaphylaxis in your medical history for a diagnosis. Food allergy is a serious medical These tests may include: LUNG: Shortness of breath, condition affecting up to 32 million wheezing, repetitive cough people in the United States, including ● Skin prick test 1 in 13 children. Food allergy happens ● Blood test HEART: Pale or bluish skin, when your body’s immune defenses ● Oral food challenge faintness, weak pulse, dizziness that normally fight disease attack a ● Trial elimination diet food protein instead. The food protein THROAT: Tight or hoarse throat, is called an allergen, and your body’s Oral food challenges are considered the trouble breathing or swallowing response is called an allergic reaction. gold standard for definitive diagnosis. MOUTH: Significant swelling of the How common are nut allergies? Depending on your medical history and tongue or lips initial test results, you may need to take Nine foods account for a majority of more than one test before receiving your SKIN: Many hives over body, reactions: milk, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts, diagnosis. widespread redness soy, wheat, fish, sesame and shellfish. -

Garlic Sesame Pork Tacos with Spicy Slaw and Roasted Peanuts

In your box 6 Small Flour Tortillas ½ oz. Roasted Peanuts 3 oz. Shredded Red Cabbage 2 tsp. Sriracha .203 fl. oz. Tamari Soy Sauce 3 fl. oz. Garlic Sesame Sauce .84 oz. Mayonnaise 5 oz. Sliced Bok Choy 2 Green Onions Customize It Options 10 oz. Sliced Pork 8 oz. Shrimp 12 oz. Antibiotic-Free Boneless Skinless Chicken Breasts 10 oz. USDA Choice Sliced Flank Steak 10 oz. Steak Strips *Contains: eggs, wheat, peanuts, soy You will need Olive Oil Mixing Bowl, Large Non-Stick Pan Minimum Internal Protein Temperature 145° Steak Pork Lamb Seafood 160° Ground Beef Ground Pork 165° Chicken Ground Turkey Classic Meal Kit Garlic Sesame Pork Tacos with spicy slaw and roasted peanuts NUTRITION per serving–Calories: 770, Carbohydrates: 55g, Sugar: 11g, Fiber: 4g, Protein: 48g, Sodium: 1671mg, Fat: 38g, Saturated Fat: 10g Prep & Cook Time Cook Within Difficulty Level Spice Level Processed in a facility that also processes peanut, tree nut, wheat, egg, soy, milk, fish, and shellfish ingredients. *Nutrition & allergen information varies based on menu selection and ingredient availability. Review protein and meal labels for updated information. 15-20 min. 5 days Easy Mild Before you cook All cook times are approximate based on testing. • If using fresh produce, thoroughly rinse and pat dry • Ingredient(s) used more than once: green onions Customize It Instructions • If using steak strips or flank steak, follow same 1. Prepare the Ingredients 2. Make the Slaw instructions as sliced pork in Steps 1 and 3, cooking until • Trim and thinly slice green onions on an angle, keeping white • In a mixing bowl, combine cabbage, mayonnaise, and no pink remains and steak strips reach minimum internal and green portions separate. -

Allergens Marked in Red;

updated 8.2021 allergens marked in red; * = item can be soy fish dairy garlic nuts onion eggs gluten modified or shellfish nitrates peanuts pineapple sesame refined sugar removed tacos *sesame oil in ahi tuna tatako *in vinaigrette *in slaw *in soy glaze tuna *in soy glaze dressing + seeds in taco *cooked in same *in chipotle *in slaw + *soybean oil in *in baja slaw baja fish fryer as oysters cod *in baja slaw (ask guest) adobo sauce garnish baja slaw (mayo) (mayo) seared chorizo in spice blend *garnish in spice blend *almonds *almonds in cauliflower *in romesco *garnish (possible cross- romesco contamination) in green chorizo spiced chicken paste + tomatillo *in tomatillo verde avocado salsa avocado salsa in tzatziki + falafel *yogurt in in falafels tzatziki sauce falafels *soy oil in buttermilk *garlic in *onions in *in remoulade *in remoulade crispy oyster oysters remoulade marinade remoulade remoulade (mayo) sauce (mayo) duck in cure *in tamarind *in tamarind sauce + garnish sauce in cure + sauce + pork belly *in sauce *garnish + sauce pickled red onion *queso fresco + mushroom in marinade *garnish in poblano sauce chile lime in escabeche shrimp in salsa macha shrimp brine in marinade and in marinade and in marinade and sesame ribeye in kimchi in marinade in marinade kimchi kimchi kimchi updated 8.2021 allergens marked in red; * = item can be soy fish dairy garlic nuts onion eggs gluten modified or shellfish nitrates peanuts pineapple sesame refined sugar removed rice bowls ahi tuna rice *in rice bowl *in dressing + *in vinaigrette -

Sesame Allergy: the Facts

Sesame Allergy: The Facts This Factsheet aims to answer some of the questions which you and your family might have about living with allergy to sesame seeds. Our aim is to provide information that will help you minimise risks and know how to treat an allergic reaction should it occur. If you know or suspect you may be allergic to sesame, the key message is to seek medical advice by visiting your GP. Your GP may need to refer you to an allergy clinic. Throughout the text you will see brief medical references given in brackets. More complete references are published towards the end of this Factsheet. How many people in the UK have sesame allergy? No one knows for sure, but the incidence of sesame seed allergy appears to have risen dramatically over the past two decades and this rise is probably linked to its increased use. Other seeds can cause allergic reactions but sesame appears to the most common to do so (Patel & Bahna, 2016). Sesame allergy can appear in childhood and, according to at least one study, persists in 80 per cent of the cases. Those who outgrow it are likely to have done so by the age of around six (Cohen et al., 2007). Sesame allergy can also begin in adulthood. Symptoms triggered by sesame The symptoms of a food allergy, including sesame allergy, may come on rapidly. Mild symptoms may include nettle rash anywhere on the body (otherwise known as hives or urticaria), or a tingling or itchy feeling in the mouth. More serious symptoms (anaphylaxis) are uncommon but remain a possibility for some people. -

Gluten, Crustaeceans, Fish, Eggs, Peanuts, Soyabeans, Nuts, Milk, Celery, Mustard, Sesame, Sulphites, Lupin, Molluscs

GLUTEN, CRUSTAECEANS, FISH, EGGS, PEANUTS, SOYABEANS, NUTS, MILK, CELERY, MUSTARD, SESAME, SULPHITES, LUPIN, MOLLUSCS BREAKFAST - BRUNCH Avocado,feta,Toast Gluten sulphites milk Gluten free if no bread, Sulphite free if no dressing Scram Gluten sulphites milk egg Gluten free if no bread, Sulphite free if no dressing eggs,tom,olive,feta,toast Avocado,haloumi,tom Gluten sulphites milk egg Gluten free if no bread, Sulphite free if no dressing salad,toast Omelette Gluten sulphites milk egg sesame Poached Nuts Gluten sulphites milk egg sesame eggs,greens,feta,seeds,toast peanuts Scram eggs,smoked Gluten sulphites egg fish salmon,avocado,toast Full veggie English Gluten sulphites egg soy mustard Shakshuka,sehug,tahini,challah Gluten sesame Lupin egg sulphites celery Pancakes Gluten egg milk Porridge Gluten milk sulphites Muesli Gluten milk LUNCH Soup of the Day,toast Ask For details Haloumi burger Gluten egg milk lupin Greek salad sulphites milk Head Room salad sulphites sesame Haloumi salad sulphites milk gluten Salmon Teriyaki & Quinoa Fish soya sulphites sesame celery salad Tuna Nicoise salad sulphites fish Falafel in Pita Gluten sulphites sesame Fish goujons, chips, salad Fish gluten Sulphites SMALL PLATES Crispy cauliflower Gluten sesame sulphites Salmon Teriyaki skewers Fish soya sulphites sesame celery Fries Gluten Side salad sulphites Hummus & pita sesame sulphites Falafel, pita, tahina Gluten sesame sulphites Haloumi Chips Gluten milk egg Sauteed greens JACKET POTATOES sulphites Sulphites in salad dressing Shakshuka sauce sesame celery -

An Update on Food Allergen Management and Global Labeling

An Update on Food Allergen Management and Global Labeling Regulations A Thesis SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Xinyu Diao IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE Advisor: David Smith, Ph.D. Aug 2017 © {Xinyu Diao} {2017} Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor Dr. David Smith for his guidance and support throughout my Master’s program. With his advice to join the program, my wonderful journey at the University of Minnesota began. His tremendous support and encouragement motivates me to always dream big. I would like to also thank Dr. Jollen Feritg, Dr. Len Marquart and Dr. Adam Rothman for being willing to take their valuable time to serve as my committee members. I am grateful to many people whose professional advice is invaluable over the course of this project. I would like to take this opportunity to show appreciation for Dr. Gerald W. Fry for being a role model for me as having lifetime enthusiasm for the field you study. I wouldn’t be where I am now without the support of my friends. My MGC (Graduate Student Club) friends who came all around the world triggered my initial interest to investigate a topic which has been concerned in a worldwide framework. Finally, I would like to give my most sincere gratitude to my family, who provide me such a precious experience of studying abroad and receiving superior education. Thank you for your personal sacrifices and tremendous support when I am far away from home. i Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my father, Hongquan Diao and my mother, Jun Liu for their unconditional love and support. -

Garden Cress Seeds: Chemistry, Medicinal Properties, Application in Dairy and Food Industry: a Review

emergent Life Sciences Research Review Article Garden Cress Seeds: chemistry, medicinal properties, application in dairy and food industry: A Review Bhaswati Lahiri, Rekha Rani Abstract Lepidium sativum also known as Garden Cress seeds contains several medicinal properties such as antioxidant properties, anti-anemic properties, anti-diabetic properties, anti-inflammatory properties, hepatoprotective Received: 19 June 2020 properties, antimicrobial properties and chemoprotective properties. It can also Accepted: 10 August 2020 Online: 12 August 2020 be used to develop functional foods by fortification. Since the ancient period Garden Cress seeds have been used for medicinal purposes. It also has Authors: application in several diseases like asthma, diarrhea, in many skin diseases Bhaswati Lahiri , Rekha Rani Department of Dairy Technology, such as scurvy, etc. It is also useful for increasing the milk secretions in Warner College of Dairy Technology, lactating mothers. Garden Cress seeds contain a remarkable amount of Sam Higginbottom University of Agriculture, Technology and Sciences, Prayagraj, India calcium, iron, folic acid, Vitamin A, and Vitamin C. Their higher protein and lipid contents indicate that the seeds serve high energy. Its methionine is [email protected] beneficial in the digestion process as well as plays an important role in the burning of fat and lysine is important in the nitrogen balance. Garden Cress Emer Life Sci Res (2020) 6(2): 1-4 seeds are used in the fortification of food and dairy products like Dahiwala bread, omega-3-fatty acid-rich biscuits, iron-rich biscuits, health drinks, E-ISSN: 2395-6658 P-ISSN: 2395-664X vegetable oils blended with alpha-linoleic acid-rich Garden Cress oil, fortified burfi, fortified chikki etc. -

Perilla Frutescens) and Sesame (Sesamum Indicum) Seeds

foods Article Metabolite Profiling and Chemometric Study for the Discrimination Analyses of Geographic Origin of Perilla (Perilla frutescens) and Sesame (Sesamum indicum) Seeds 1, 1, 2 3 4 Tae Jin Kim y, Jeong Gon Park y, Hyun Young Kim , Sun-Hwa Ha , Bumkyu Lee , Sang Un Park 5 , Woo Duck Seo 2,* and Jae Kwang Kim 1,* 1 Division of Life Sciences, College of Life Sciences and Bioengineering, Incheon National University, Incheon 22012, Korea; [email protected] (T.J.K.); [email protected] (J.G.P.) 2 Division of Crop Foundation, National Institute of Crop Science, Rural Development Administration, Wanju, Jeonbuk 55365, Korea; [email protected] 3 Department of Genetic Engineering and Graduate School of Biotechnology, Kyung Hee University, Yongin 17104, Korea; [email protected] 4 Department of Environment Science & Biotechnology, Jeonju University, Jeonju 55069, Korea; [email protected] 5 Department of Crop Science, Chungnam National University, 99 Daehak-ro, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon 34134, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (W.D.S.); [email protected] (J.K.K.); Tel.: +82-63-238-5305 (W.D.S.); +82-32-835-8241 (J.K.K.) These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 26 June 2020; Accepted: 21 July 2020; Published: 24 July 2020 Abstract: Perilla and sesame are traditional sources of edible oils in Asian and African countries. In addition, perilla and sesame seeds are rich sources of health-promoting compounds, such as fatty acids, tocopherols, phytosterols and policosanols. Thus, developing a method to determine the geographic origin of these seeds is important for ensuring authenticity, safety and traceability and to prevent cheating. -

Apr2018training.Pdf

AccommodatingChildrenwithSpecial Dietary Needs in the School Nutrition Programs; Guidance for School Foodservice Staff Celiac disease evidence analysis project. Celiac disease (CD) evidence-based nutrition practice guideline. Wheat allergy. Wheat allergy symptoms. The gluten-free nutrition guide. Guidance related to the ADAamendments act. Food allergies: What you need to know. Celiac Disease Food Allergens Food Allergy: Tree Nut & Wheat Post Test – April 2018 Please keep this test and certificate in your files for Licensing. You do not need to send it in to our office or the State. 1. Disclosure on food labels of all tree nuts is required by _____. 2. Tree nuts tend to cause particularly severe ______ _______, even if very small amounts are consumed. 3. Tree nuts can be found in household products such as lotions and soaps. True or False? 4. A product that is labeled as being produced in a facility with tree nuts can be safely consumed by an individual with a tree nut allergy. True or False? 5. Nutmeg and water chestnuts are safe for a person with tree nut allergies because nutmeg is a _______and water chestnut is a _______. 6. Wheat allergy is an abnormal immune system reaction to one of the four _________ found in wheat: gluten, albumin, globulin, gliadin. 7. Many condiments such as soy sauce, ketchup and mustard can contain wheat. True or False? 8. Barley, chickpea, cornmeal and quinoa are all considered good wheat alternatives. True or False? 9. Life‐threatening food allergies are considered ____________. 10. Celiac disease is an inherited or genetic autoimmune disease characterized by sensitivity to the protein ___________. -

Complete Plastome Sequences from Bertholletia Excelsa and 23 Related Species Yield Informative Markers for Lecythidaceae

GENOMIC RESOURCES ARTICLE Complete plastome sequences from Bertholletia excelsa and 23 related species yield informative markers for Lecythidaceae Ashley M. Thomson1,2*, Oscar M. Vargas1* , and Christopher W. Dick1,3 Manuscript received 1 October 2017; revision accepted PREMISE OF THE STUDY: The tropical tree family Lecythidaceae has enormous ecological and 11 January 2018. economic importance in the Amazon basin. Lecythidaceae species can be difficult to identify 1 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of without molecular data, however, and phylogenetic relationships within and among the most Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, USA diverse genera are poorly resolved. 2 Faculty of Natural Resources Management, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario P7B 5E1, Canada METHODS: To develop informative genetic markers for Lecythidaceae, we used genome 3 Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Panama City skimming to de novo assemble the full plastome of the Brazil nut tree (Bertholletia excelsa) 0843-03092, Republic of Panama and 23 other Lecythidaceae species. Indices of nucleotide diversity and phylogenetic signal 4 Author for correspondence: [email protected] were used to identify regions suitable for genetic marker development. *These authors contributed equally to this work. RESULTS: The B. excelsa plastome contained 160,472 bp and was arranged in a quadripartite Citation: Thomson, A. M., O. M. Vargas, and C. W. Dick. 2018. structure. Using the 24 plastome alignments, we developed primers for 10 coding and non- Complete plastome sequences from Bertholletia excelsa and 23 related species yield informative markers for Lecythidaceae. coding DNA regions containing exceptional nucleotide diversity and phylogenetic signal. We Applications in Plant Sciences 6(5): e1151. -

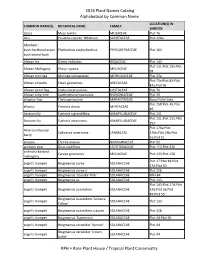

2016 Plant Names Catalog Alphabetical by Common Name

2016 Plant Names Catalog Alphabetical by Common Name LOCATION(S) IN COMMON NAME(S) BOTANICAL NAME FAMILY GARDEN abaca Musa textilis MUSACEAE Plot 76 abiu Pouteria caimito 'Whitman' SAPOTACEAE Plot 128a Abraham- bush:hardhead:scipio- Phyllanthus epiphyllanthus PHYLLANTHACEAE Plot 164 bush:sword-bush African iris Dietes iridioides IRIDACEAE Plot 143 Plot 131:Plot 19a:Plot African Mahogany Khaya nyasica MELIACEAE 58 African moringa Moringa stenopetala MORINGACEAE Plot 32a Plot 71a:Plot 83:Plot African oil palm Elaeis guineensis ARECACEAE 84a:Plot 96 African spiral flag Costus lucanusianus COSTACEAE Plot 76 African tulip-tree Spathodea campanulata BIGNONIACEAE Plot 29 alligator flag Thalia geniculata MARANTACEAE Royal Palm Lake Plot 158:Plot 45:Plot allspice Pimenta dioica MYRTACEAE 46 Amazon lily Eucharis x grandiflora AMARYLLIDACEAE Plot 131 Plot 131:Plot 151:Plot Amazon-lily Eucharis amazonica AMARYLLIDACEAE 152 Plot 176a:Plot American beauty Callicarpa americana LAMIACEAE 176b:Plot 19b:Plot berry 3a:Plot 51 anaqua Ehretia anacua BORAGINACEAE Plot 52 anchovy pear Grias cauliflora LECYTHIDACEAE Plot 112:Plot 32b andiroba:bastard Carapa guianensis MELIACEAE Plot 133:Plot 158 mahogany Plot 17:Plot 18:Plot angel's trumpet Brugmansia aurea SOLANACEAE 27d:Plot 50 angel's trumpet Brugmansia aurea x SOLANACEAE Plot 32b angel's trumpet Brugmansia 'Ecuador Pink' SOLANACEAE RPH-B4 angel's trumpet Brugmansia sp. SOLANACEAE Plot 133 Plot 143:Plot 27d:Plot angel's trumpet Brugmansia suaveolens SOLANACEAE 32b:Plot 3a:Plot 49:Plot 50 Brugmansia suaveolens