Notes on the Thai-Burma Railway Part Ii: Asian Romusha; the Silenced Voices of History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Changi Chapel and Museum 85

LOCALIZING MEMORYSCAPES, BUILDING A NATION: COMMEMORATING THE SECOND WORLD WAR IN SINGAPORE HAMZAH BIN MUZAINI NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2004 LOCALIZING MEMORYSCAPES, BUILDING A NATION: COMMEMORATING THE SECOND WORLD WAR IN SINGAPORE HAMZAH BIN MUZAINI B.A. (Hons), NUS A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ‘Syukor Alhamdulillah!’ With the aid of the Almighty Allah, I have managed to accomplish the writing of this thesis. Thank god for the strength that has been bestowed upon me, without which this thesis might not have been possible indeed. A depth of gratitude to A/P Brenda Yeoh and A/P Peggy Teo, without whose guidance and supervision, I might not have been able to persevere with this endeavour. Thank you for your limitless patience and constant support throughout the two years. To A/P Brenda Yeoh especially: thanks for encouraging me to do this and also for going along with my “conference-going” frenzy! It made doing my Masters all that more exciting. A special shout-out to A. Jeyathurai, Simon Goh and all the others at the Singapore History Consultants and Changi Museum who introduced me to the amazing, amazing realm of Singapore’s history and the wonderful, wonderful world of historical research. Your support and friendship through these years have made me realize just how critical all of you have been in shaping my interests and moulding my desires in life. I have learnt a lot which would definitely hold me in good stead all my life. -

Transportation on the Minneapolis Riverfront

RAPIDS, REINS, RAILS: TRANSPORTATION ON THE MINNEAPOLIS RIVERFRONT Mississippi River near Stone Arch Bridge, July 1, 1925 Minnesota Historical Society Collections Prepared by Prepared for The Saint Anthony Falls Marjorie Pearson, Ph.D. Heritage Board Principal Investigator Minnesota Historical Society Penny A. Petersen 704 South Second Street Researcher Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 Hess, Roise and Company 100 North First Street Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 May 2009 612-338-1987 Table of Contents PROJECT BACKGROUND AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................. 1 RAPID, REINS, RAILS: A SUMMARY OF RIVERFRONT TRANSPORTATION ......................................... 3 THE RAPIDS: WATER TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS .............................................. 8 THE REINS: ANIMAL-POWERED TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ............................ 25 THE RAILS: RAILROADS BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ..................................................................... 42 The Early Period of Railroads—1850 to 1880 ......................................................................... 42 The First Railroad: the Saint Paul and Pacific ...................................................................... 44 Minnesota Central, later the Chicago, Milwaukee and Saint Paul Railroad (CM and StP), also called The Milwaukee Road .......................................................................................... 55 Minneapolis and Saint Louis Railway ................................................................................. -

Chungkai Hospital Camp | Part One: Mid-October 1942 to Mid-May 1944 " Sears Eldredge Macalester College

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Book Chapters Captive Audiences/Captive Performers 2014 Chapter 6a. "Chungkai Showcase": Chungkai Hospital Camp | Part One: Mid-October 1942 to Mid-May 1944 " Sears Eldredge Macalester College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/thdabooks Recommended Citation Eldredge, Sears, "Chapter 6a. "Chungkai Showcase": Chungkai Hospital Camp | Part One: Mid-October 1942 to Mid-May 1944 "" (2014). Book Chapters. Book 16. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/thdabooks/16 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Captive Audiences/Captive Performers at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 184 Chapter 6: “Chungkai Showcase” Chungkai Hospital Camp Part One: Mid-October 1942 to to Mid-May 1944 FIGURE 6.1. CHUNGKAI THEATRE LOGO. HUIB VAN LAAR. IMAGE COPYRIGHT MUSEON, THE HAGUE, NETHERLANDS. Though POWs in other camps in Thailand produced amazing musical and theatrical offerings for their audiences, it was the performers in Chungkai who, arguably, produced the most diverse, elaborate, and astonishing entertainment on the Thailand-Burma railway. Between Christmas 1943 and May 1945 they presented over sixty-five musical or theatrical productions. As there is more detailed information about the administration, production, and reception of the entertainment at Chungkai than at any other camp on the railway, the focus in this chapter will be on those productions and personalities that stand out in some significant way artistically, technically, or politically. To cover this material adequately, the chapter will be divided into two parts: Part One will cover the period from mid-October 1942 to mid-May 1944; Part Two, from mid-May 1944 to July 1945. -

Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the National Archives

REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 116 Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the national archives 1 Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the National Archives REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 116 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC Compiled by Peter F. Brauer 2010 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Records relating to railroads in the cartographic section of the National Archives / compiled by Peter F. Brauer.— Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, 2010. p. ; cm.— (Reference information paper ; no 116) includes index. 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Cartographic and Architectural Branch — Catalogs. 2. Railroads — United States — Armed Forces — History —Sources. 3. United States — Maps — Bibliography — Catalogs. I. Brauer, Peter F. II. Title. Cover: A section of a topographic quadrangle map produced by the U.S. Geological Survey showing the Union Pacific Railroad’s Bailey Yard in North Platte, Nebraska, 1983. The Bailey Yard is the largest railroad classification yard in the world. Maps like this one are useful in identifying the locations and names of railroads throughout the United States from the late 19th into the 21st century. (Topographic Quadrangle Maps—1:24,000, NE-North Platte West, 1983, Record Group 57) table of contents Preface vii PART I INTRODUCTION ix Origins of Railroad Records ix Selection Criteria xii Using This Guide xiii Researching the Records xiii Guides to Records xiv Related -

Despatches Summer 2016 July 2016

Summer 2016 www.gbg-international.com DESPATCHES IN THIS ISSUE: PLUS Battlefield Guide On The River Kwai Verdun 1916 - The Longest Battle The Ardennes and Back Again AND Roman Guides Guide Books 02 | Despatches FIELD guides Our cover image: Dr John Greenacre brushing up on the facts at the Sittang River, Myanmar. Andrew Thomson explaining the Siegfried Line, Hurtgen Forest, Germany German trenches in the Bois d’Apremont, St Mihiel. www.gbg-international.com | 03 Contents P2 FIELD guides P18-20 TESTING THE TESTUDO A Guild project P5-11 HELP FOR HEROES IN THAILAND P21 FIELD guides AND MYANMAR An Opportunity Grasped P22-25 VERDUN The Longest Battle P12-16 A TALE OF TWO TOURS Two different perspectives P25 EVENT guide 2016 P17 FIELD guides P26-27 GUIDE books Under The Devil’s Eye, newly joined Associate Member, Alan Wakefield explaining the intricacies of The Birdcage Line outside Thessaloniki. (Picture StaffRideUK) 04 | Despatches OPENING shot: THE CHAIRMAN’S VIEW Welcome fellow members, Guild Partners, and positive. The cream will rise to the top and those at the Supporters to the Summer 2016 edition of fore of our trade will take those that want to raise their Despatches, the house magazine of the Guild. individual and collective standards with them. These The year so far has been dominated by FWW interesting times offer great opportunities for the commemorative events marking the centenaries of Guild. Our validation programme is an ideal vehicle Jutland, Verdun and the Somme. Recent weeks have for those seeking self-improvement and, coupled with seen the predominantly Australian ceremonies at our shared aims, encourages the raising of collective Fromelles and Pozieres. -

The Illustrated Winespeak Free

FREE THE ILLUSTRATED WINESPEAK PDF Ronald Searle | 104 pages | 01 Jun 1994 | Souvenir Press Ltd | 9780285625921 | English | London, United Kingdom The Illustrated Winespeak: Ronald Searle's Wicked World of Winetasting by Ronald Searle Please sign in to write a review. If you have changed your email address then contact us and we will update your details. Would you like to proceed to the App store to download the Waterstones App? We have recently updated our Privacy Policy. The Illustrated Winespeak site uses cookies The Illustrated Winespeak offer you a better experience. By continuing to browse the site you accept our Cookie Policy, you can change your settings at any time. In stock Usually dispatched within 24 hours. Quantity Add to basket. This item has been added to your basket View basket Checkout. Your local Waterstones may have stock of this item. On The Illustrated Winespeak's first publication inthis hilarious send-up of winetaster's jargon was hailed by 'The Financial Times' as "one of this year's bubbling successes". It has since been constantly reprinted to meet demand and has become a classic of The Illustrated Winespeak kind. For all those mystified by the strange pontifications of wine-buffs, Ronald Searle's The Illustrated Winespeak is the perfect guide to the meaning behind "distinctive nose", "full bodied" and "elegant but lacks backbone". The book is an onslaught on the pretentious nonsense written and spoken about wine. His interpretations of such apparently innocent phrases as 'full bodied' and 'distinctive nose' The Illustrated Winespeak certainly make you laugh aloud, and in all probability splutter in your wine glass. -

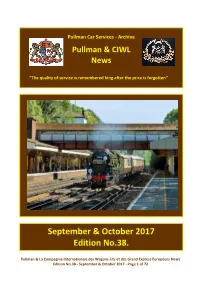

Pullman Car Services - Archive

Pullman Car Services - Archive Pullman & CIWL News “The quality of service is remembered long after the price is forgotten” September & October 2017 Edition No.38. Pullman & La Compagnie Internationale des Wagons -Lits et des Grand Express Européens News Edition No.38 - September & October 2017 - Page 1 of 72 COVER PHOTOGRAPH: Paul Blowfield - Communications & Marketing Officer, MNLPS - www.clan-line.org July 5th, 2017, marking 50 years to the day that the last steam hauled ‘Bournemouth Belle’ ran. The Merchant Navy Locomotive Preservation Society No.35028 Clan Line with ‘The Bournemouth Belle’ (Belmond British Pullman Cars) passing through Weybridge Station on the ‘Down’ main line. From the Coupé. Welcome aboard your bi-monthly newsletter. I take this opportunity to thank those readers who have kindly taken time to forward contributions in the form of articles and photographs for this edition. I remain dependent on contributions of news, articles (Word) and photographs (jpg) formats in all aspects of Pullman and CIWL operations both past, present, future and related aspects within model railways. All I ask of you for the time I spend in producing your newsletter, is for you to forward on by either E-mail or printing a copy, to any one you believe would be interested in reading your newsletter. Publication of the newsletter being scheduled on or about the 1st of January, March, May, July, September and November. The next edition editorial deadline date of Saturday October 28th, with the scheduled publication date of Wednesday November 1st, 2017. The views and articles within this publication are not necessarily those of the editor. -

Union Depot Tower Interlocking Plant

Union Depot Tower Union Depot Tower (U.D. Tower) was completed in 1914 as part of a municipal project to improve rail transportation through Joliet, which included track elevation of all four railroad lines that went through downtown Joliet and the construction of a new passenger station to consolidate the four existing passenger stations into one. A result of this overall project was the above-grade intersection of 4 north-south lines with 4 east-west lines. The crossing of these rail lines required sixteen track diamonds. A diamond is a fixed intersection between two tracks. The purpose of UD Tower was to ensure and coordinate the safe and timely movement of trains through this critical intersection of east-west and north-south rail travel. UD Tower housed the mechanisms for controlling the various rail switches at the intersection, also known as an interlocking plant. Interlocking Plant Interlocking plants consisted of the signaling appliances and tracks at the intersections of major rail lines that required a method of control to prevent collisions and provide for the efficient movement of trains. Most interlocking plants had elevated structures that housed mechanisms for controlling the various rail switches at the intersection. Union Depot Tower is such an elevated structure. Source: Museum of the American Railroad Frisco Texas CSX Train 1513 moves east through the interlocking. July 25, 1997. Photo courtesy of Tim Frey Ownership of Union Depot Tower Upon the completion of Union Depot Tower in 1914, U.D. Tower was owned and operated by the four rail companies with lines that came through downtown Joliet. -

E&O Fact Sheet.Pub

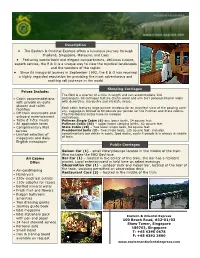

Description • The Eastern & Oriental Express offers a luxurious journey through Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, and Laos • Featuring comfortable and elegant compartments, delicious cuisine, superb service, the E & O is a unique way to view the mystical landscapes and the wonders of the region • Since its inaugural journey in September 1993, the E & O has received a highly regarded reputation for providing the most adventurous and exciting rail journeys in the world Sleeping Carriages Prices Include: The E&O is a quarter of a mile in length and can accommodate 126 • Cabin accommodations passengers. All carriages feature cherry wood and elm burr paneled interior walls with private en-suite with decorative marquetry and intricate inlays. shower and toilet Each cabin features large picture windows for an excellent view of the passing scen- facilities ery. Luggage is limited to 60 pounds per person for the Pullman and State cabins. • Off train excursions and The Presidential suites have no luggage onboard entertainment restrictions. • Table d’ hôte meals Pullman Single Cabin (6) -one lower berth, 54 square feet • All applicable taxes Pullman Cabin (30) – upper/lower sleeping births, 62 square feet • Complimentary Mail State Cabin (28) – Two lower single beds, 84 square feet service Presidential Suite (2) – Two single beds, 125 square feet. Includes • Limited selection of complimentary bar drinks in cabin, Ipod docks, seats 4 people & is always in middle magazines and daily of train. English newspaper Public Carriages Saloon Car (1) - small library/lounge located in the middle of the train. Also includes the E&O Boutique All Cabins Bar Car (1) – located in the center of the train, the bar has a resident Offer: pianist. -

“The Bridge on the River Kwai”

52 วารสารมนุษยศาสตร์ ฉบับบัณฑิตศึกษา “The Bridge on the River Kwai” - Memory Culture on World War II as a Product of Mass Tourism and a Hollywood Movie Felix Puelm1 Abstract During World War II the Japanese army built a railway that connected the countries of Burma and Thailand in order to create a safe supply route for their further war campaigns. Many of the Allied prisoners of war (PoWs) and the Asian laborers that were forced to build the railway died due to dreadful living and working conditions. After the war, the events of the railway’s construction and its victims were mostly forgotten until the year 1957 when the Oscar- winning Hollywood movie “The Bridge on the River Kwai” visualized this tragedy and brought it back into the public memory. In the following years western tourists arrived in Kanchanaburi in large numbers, who wanted to visit the locations of the movie. In order to satisfy the tourists’ demands a diversified memory culture developed often ignoring historical facts and geographical circumstances. This memory culture includes commercial and entertaining aspects as well as museums and war cemeteries. Nevertheless, the current narrative presents the Allied prisoners of war at the center of attention while a large group of victims is set to the outskirts of memory. Keywords: World War II, Memory Culture, Kanchanaburi, River Kwai, Japanese Atrocities Introduction Kanchanaburi in western Thailand has become an internationally well-known symbol of World War II in Southeast Asia and the Japanese atrocities. Every year more than 4 million tourists are attracted by the historical sites. At the center of attention lies a bridge that was once part of the Thailand-Burma Railway, built by the Japanese army during the war. -

Dr Charles Rowland B Richards at the Medicine Ceremony Held at 4.00Pm on 24 November 2006

Dr Charles Rowland ("Rowley") B Richards The degree of Doctor of Medicine (honoris causa) was conferred upon Dr Charles Rowland B Richards at the Medicine ceremony held at 4.00pm on 24 November 2006. The Chancellor the Hon Justice Kim Santow conferring the honorary degree upon Dr Richards, photo, copyright Memento Photography. Citation Chancellor, I have the honour to present Charles Rowland Bromley Richards for admission to the degree of Doctor of Medicine, honoris causa. Rowley Richards, was born in Sydney in 1916 and grew up in Summer Hill. Both his parents were profoundly deaf and the way they overcame daily challenges had a strong influence on their young son. Rowley graduated MBBS from the University of Sydney in 1939. He enlisted in the AIF as a medical officer and served in the Malayan campaign of 1941-42 before being imprisoned by the Japanese following the fall of Singapore in 1942. He was a prisoner of war in Changi Prison before being sent to the infamous Burma Railway. Later he was sent to a slave labour camp in the north of Japan, surviving shipwreck on the way, a harsh winter and infection with smallpox just prior to liberation. On return to Australia, when these things became known, he was Mentioned in Dispatches for his service as a regimental medical officer whilst a prisoner of war. In 1969 he was awarded an MBE for his services in war and peace. He also earned the Efficiency Decoration. Since his return he has supported other survivors of Japanese prisoner of war camps and their families through his role as President of the 2/15th Field Regiment Association, and his long service as president of the 8th Australian Division Association. -

Rail & Sail Asia Eastern & Oriental Express 6-Night Pre

Rail & Sail Asia Eastern & Oriental Express 6-Night Pre-voyage Land Journey Program Begins in: Bangkok Program Concludes in: Singapore Available on these Sailings: 11-Apr-2020 Selling price from: Please call to discuss cabin options and pricing Call 1-855-AZAMARA to reserve your Land Journey Board the Eastern & Oriental Express and journey from Bangkok to Singapore in true classic fashion. Begin with a few days amid the ornate shrines and vibrant streets of the Thai capital. Then, it’s all aboard for a ride that will remain in your heart forever. Along the way, you’ll savor gourmet cuisine and enjoy a host of possibilities—from touring rice paddies and participating in a local cooking class, trekking through the Malaysian hills. Discover the cultural riches and natural beauty of Asia on a tour that gives you plenty of ways to embrace them both. Many nationals, including US and UK citizens, do not require a visa to enter Thailand or Singapore. Please check with your travel professional or directly with the Thai Embassy to confirm your specific travel document requirements. All Passport details should be confirmed at the time of booking. Passport should have at least 6 months validity at the time of travel. Sales of this program close 90 days prior; book early to avoid disappointment, as space is limited. HIGHLIGHTS: ● Bangkok: Enjoy a guided tour that visits the Grand Palace and famed Reclining Buddha. ● Eastern & Oriental Express: Spend three nights on this luxurious train, stopping along the way to discover the wonders of Asia. Savor daily four-course dinners and three-course lunches.