The Changi Chapel and Museum 85

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government Financial Statements for the Financial Year 2020/2021

GOVERNMENT FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/2021 Cmd. 10 of 2021 ________________ Presented to Parliament by Command of The President of the Republic of Singapore. Ordered by Parliament to lie upon the Table: 28/07/2021 ________________ GOVERNMENT FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR by OW FOOK CHUEN 2020/2021 Accountant-General, Singapore Copyright © 2021, Accountant-General's Department Mr Lawrence Wong Minister for Finance Singapore In compliance with Regulation 28 of the Financial Regulations (Cap. 109, Rg 1, 1990 Revised Edition), I submit the attached Financial Statements required by section 18 of the Financial Procedure Act (Cap. 109, 2012 Revised Edition) for the financial year 2020/2021. OW FOOK CHUEN Accountant-General Singapore 22 June 2021 REPORT OF THE AUDITOR-GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE GOVERNMENT OF SINGAPORE Opinion The Financial Statements of the Government of Singapore for the financial year 2020/2021 set out on pages 1 to 278 have been examined and audited under my direction as required by section 8(1) of the Audit Act (Cap. 17, 1999 Revised Edition). In my opinion, the accompanying financial statements have been prepared, in all material respects, in accordance with Article 147(5) of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (1999 Revised Edition) and the Financial Procedure Act (Cap. 109, 2012 Revised Edition). As disclosed in the Explanatory Notes to the Statement of Budget Outturn, the Statement of Budget Outturn, which reports on the budgetary performance of the Government, includes a Net Investment Returns Contribution. This contribution is the amount of investment returns which the Government has taken in for spending, in accordance with the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore. -

Tour Description World Express Offers a Wide Choice of Sightseeing Tours, Which Offer Visitors an Interesting Experience of the Sights and Sounds of Singapore

TOUR DESCRIPTION WORLD EXPRESS OFFERS A WIDE CHOICE OF SIGHTSEEING TOURS, WHICH OFFER VISITORS AN INTERESTING EXPERIENCE OF THE SIGHTS AND SOUNDS OF SINGAPORE 1 CITY TOUR 1 PERANAKAN TRAIL (with food tasting) SIN-1 3 /2 hrs SIN-4 3 /2 hrs An orientation tour that showcases the history, multi racial culture and lifestyle that is Join us on a colourful journey into the history, lifestyle and unique character of the SINGAPORE Singapore. Peranakan Babas (the men) and Nonyas (the women)… A walk through a Spice Garden – the original site of the first Botanic Gardens will uncover See the city’s colonial heritage as we drive around the Civic District past the Padang, the the intricacies of spices and herbs that go into Peranakan cooking. Cricket Club, Parliament House, Supreme Court and City Hall. Stop at the Merlion Park for great views of Marina Bay and a picture-taking opportunity with the Merlion, a mythological A splendid display of Peranakan costume, embroidery, beadwork, jewellery, porcelain, creature that is part lion and part fish. The tour continues with a visit to the Thian Hock furniture, craftwork will provide a glimpse into the fascinating culture of the Nonyas Keng Temple, one of the oldest Buddhist-Taoist temples on the island, built with donation and Babas. from the early immigrants workers from China. Next drive past Chinatown to a local handicraft centre to watch Asian craftsmanship. From there we proceed to the National A visit to the bustling enclaves of Katong & Joo Chiat showcases the rich and baroque Orchid Garden, located within the Singapore Botanic Gardens, which boasts a sprawling Peranakan architecture. -

Remembering Operation Jaywick : Singapore's Asymmetric Warfare

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Remembering Operation Jaywick : Singapore’s Asymmetric Warfare Kwok, John; Li, Ian Huiyuan 2018 Kwok, J. & Li, I. H. (2018). Remembering Operation Jaywick : Singapore’s Asymmetric Warfare. (RSIS Commentaries, No. 185). RSIS Commentaries. Singapore: Nanyang Technological University. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/82280 Nanyang Technological University Downloaded on 24 Sep 2021 04:43:21 SGT Remembering Operation Jaywick: Singapore’s Asymmetric Warfare By John Kwok and Ian Li Synopsis Decades before the concept of asymmetric warfare became popular, Singapore was already the site of a deadly Allied commando attack on Japanese assets. There are lessons to be learned from this episode. Commentary 26 SEPTEMBER 2018 marks the 75th anniversary of Operation Jaywick, a daring Allied commando raid to destroy Japanese ships anchored in Singapore harbour during the Second World War. Though it was only a small military operation that came under the larger Allied war effort in the Pacific, it is worth noting that the methods employed bear many similarities to what is today known as asymmetric warfare. States and militaries often have to contend with asymmetric warfare either as part of a larger campaign or when defending against adversaries. Traditionally regarded as the strategy of the weak, it enables a weaker armed force to compensate for disparities in conventional force capabilities. Increasingly, it has been employed by non-state actors such as terrorist groups and insurgencies against the United States and its allies to great effect, as witnessed in Iraq, Afghanistan, and more recently Marawi. -

FREEMASONRY • the GAVEL V42 N1 – AUTUMN 2010 Freemason

FM_March10.QXP:Layout 1 4/03/10 4:12 PM Page 1 OUTBACK TREK • MV KRAIT • 460 SQUADRON • MUSEUM OF FREEMASONRY • THE GAVEL v42 n1 – AUTUMN 2010 Freemason Outback Trek Fundraising for the Flying Doctors MV Krait Lachlan Remembered Macquarie FM_March10.QXP:Layout 1 4/03/10 4:12 PM Page 2 CONTENTS Editorial 3 Freemason Message from the Grand Chaplain 4 The Official Journal of The Common Gavel 5 The United Grand Lodge of New South Wales and Australian Capital Territory Quarterly Communication 6 Grand Lodge Website: Famous Australians: Bert Appleroth 7 www.uglnsw.freemasonry.org.au The MV Krait 8 This issue of the Freemason is produced under 460 Squadron 10 the direction of: Chairman: RW Bro Ted Simmons OAM Have Your Say 11 Committee: RW Bro Graham Maltby (Secretary), Granny’s all-purpose apron 12 RW Bro David Standish (Marketing), Dr Yvonne McIntyre, VW Bro Mervyn Sinden, RW Bro Craig Pearce, From the Grand Secretary 13 VW Bro Andre Fettermann Questions and Answers 13 FREEMASON is the official journal of The United Grand Lodge of New South Wales and Australian Capital Fundraising Trek for Flying Doctor 14 Territory of Ancient, Free and Accepted Masons. A taste of Ireland 16 Telephone: (02) 9284 2800 The journal is published in March, June, September Tip Cards 17 and December. Deadline for copy is 1st of the month preceding month of issue. The Museum of Freemasonry 18 All matters for publication in the journal should be Governor Lachlan Macquarie 20 addressed to: The Secretary Masonic Widows 22 Publications Committee Masonic Book Club 22 The United Grand Lodge of NSW & ACT PO Box A259, Sydney South, NSW 1235 Book Reviews 23 Telephone: (02) 9284 2800 Facsimile: (02) 9284 2828 Something for the Ladies 24 Email: [email protected] Freemasons and cricket 26 Publication of an advertisement does not imply endorsement of the product or service by The United Meet the Staff 27 Grand Lodge of NSW & ACT. -

Best Hidden Gems in Singapore"

"Best Hidden Gems in Singapore" Created by: Cityseeker 17 Locations Bookmarked Singapore Philatelic Museum "Interesting Exhibits" Ever wondered how that stamp in the corner of your envelope was made? Well, that is precisely what you will learn at South-east Asia's first philatelic museum. Opened in 1995, this museum holds an extensive collection of local and international stamps dating back to the 19th century. Anything related to stamps can be found here like first day by Tanya Procyshyn covers, artwork, printing proofs, progressive sheets, even a number of private collections. Equipped with interactive exhibits, audio-visual facilities, a resource center and games, visitors are likely to come away with a new-found interest in stamp collecting. +65 6337 3888 www.spm.org.sg/ [email protected] 23-B Coleman Street, g Singapore Acid Bar "A Secluded Music Cove" Acid Bar occupies a small section of bar Peranakan Place, however do not be deceived by the modest size of this place. The bar is an intimate escape from the hustle of the city life. Illuminated in warm lights and neatly furnished with quaint seating spaces, Acid Bar is the place to enjoy refined drinks while soaking in acoustic tunes. A venue for memorable by Public Domain performances by local artists and bands, Acid Bar is a true hidden gem of the city that is high on nightlife vigor. +65 6738 8828 peranakanplace.com/outle [email protected] 180 Orchard Road, t/acidbar/ m Peranakan Place, Singapore Keepers "Singapore's Shopping Hub" Keepers is a shopping hub, located on Orchard Road. -

Australian War Memorial Annual Report 2013–2014

EPORT 2013–2014 EPORT R L A L ANNU A ORI M R ME A N W A LI A AUSTR AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2013–2014 AUSTR A LI A N W A R ME M ORI A L ANNU A L R EPORT 2013–2014 EPORT AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2013–2014 Annual report for the year ended 30 June 2014, together with the financial statements and the report of the Auditor-General Images produced courtesy of the Australian War Memorial, Canberra Cover: Their Royal Highness The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge in a moment of private reflection at the Roll of Honour. PAIU2014/078.14 Title page: ANZAC Day National Ceremony 2014. PAIU2014/073.13 Copyright © Australian War Memorial ISSN 1441 4198 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced, copied, scanned, stored in a retrieval system, recorded, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. Australian War Memorial GPO Box 345 Canberra, ACT 2601 Australia www.awm.gov.au ii AUSTR A LI A N W A R ME M ORI A L ANNU A L R EPORT 2013–2014 EPORT Her Excellency the Honourable Dame Quentin Bryce AD CVO, Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, on her final visit to the Australian War Memorial as Governor-General. His Excellency General the Honourable Sir Peter Cosgrove AK MC (Retd), Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, and His Royal Highness The Duke of Cambridge KG KT during the Anzac Day National Ceremony 2014 commemorating the 99th anniversary of the Anzac landings. -

Travel Itinerary

Travel Itinerary Page 1 of 5 PROGRAM: 16 DAYS / 13 NIGHTS ROUNDTRIP KUALA LUMPUR - CAMERON HIGHLANDS - MALACCA - JOHOR - SINGAPORE DAY 1 - WEDNESDAY 3 MARCH - DUMFRIES-GLASGOW & GALASHIELS-GLASGOW (1) Coach transfer from Dumfries to Glasgow airport (1) Coach transfer from Galashiels to Glasgow airport TO KUALA LUMPUR (VIA DUBAI) Fly from Glasgow airport Dubai on Emirates Airlines Depart Glasgow Emirates Airlines EK28 13:05 DAY 2 - THURSDAY 4 MARCH - DUBAI Arrive Dubai 00:25 Change your flight to Kuala Lumpur Depart Dubai Emirates Airlines EK346 03:10 Arrive Kuala Lumpur 14:05 Meeting, assistance on arrival and transferred to your hotel. Overnight stay at Shangri-La Kuala Lumpur for 3 nights (5 Star Hotel - Superior Room) DAY 3 - WEDNESDAY 24 FEB - KUALA LUMPUR (B/L) They say the best way to get to know a new city is through a tour. This tour will unveil the beauty and charm of the old and new Kuala Lumpur Known as the ‘Garden City of Lights’. See the contrast of the magnificent skyscrapers against building of colonial days. Places visited: Petronas Twin Towers (Photo stop) King’s Palace (Photo stop) Independent Square National Monument Royal Selangor Pewter After tour return to hotel and free at leisure. In the evening transfer to Seri Melayu Restaurant where you can savor a wide array of local dishes and delights, at the same time be entertained with a cultural show. Overnight stay at Shangri-La Kuala Lumpur. DAY 4 - THURSDAY 25 FEB - KUALA LUMPUR (B) TRAVELSERV Trademark Registered No: 2536073 Address: 38 Bridge Farm Close, Mildenhall, Suffolk. -

From Orphanage to Entertainment Venue: Colonial and Post-Colonial Singapore Reflected in the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus

From Orphanage to Entertainment Venue: Colonial and post-colonial Singapore reflected in the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus by Sandra Hudd, B.A., B. Soc. Admin. School of Humanities Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania, September 2015 ii Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the Universityor any other institution, except by way of backgroundi nformationand duly acknowledged in the thesis, andto the best ofmy knowledgea nd beliefno material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text oft he thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. �s &>-pt· � r � 111 Authority of Access This thesis is not to be made available for loan or copying fortwo years followingthe date this statement was signed. Following that time the thesis may be made available forloan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. :3 £.12_pt- l� �-- IV Abstract By tracing the transformation of the site of the former Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus, this thesis connects key issues and developments in the history of colonial and postcolonial Singapore. The convent, established in 1854 in central Singapore, is now the ‗premier lifestyle destination‘, CHIJMES. I show that the Sisters were early providers of social services and girls‘ education, with an orphanage, women‘s refuge and schools for girls. They survived the turbulent years of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore and adapted to the priorities of the new government after independence, expanding to become the largest cloistered convent in Southeast Asia. -

Stay Fit & Feel Good Memorable Events at The

INTEGRATED DINING DESTINATION SINGAPORE ISLAND MAP STAY FIT & FEEL GOOD Food warms the soul and we promise that it is always a lavish gastronomic experience Relax after a day of conference meeting or sightseeing. Stay in shape at our 24-hour gymnasium, at the Grand Copthorne Waterfront Hotel. have a leisurely swim in the pool, challenge your travel buddies to a game of tennis or soothe your muscles in the outdoor jacuzzi. MALAYSIA SEMBAWANG SHIPYARD NORTHERN NS11 Pulau MALAYSIA SEMBAWANG SEMBAWANG Seletar WOODLANDS WOODLANDS SUNGEI BULOH WETLAND CHECKPOINT TRAIN CHECKPOINT RESERVE NS10 ADMIRALTY NS8 NS9 MARSILING WOODLANDS YISHUN SINGAPORE NS13 TURF CLUB WOODLANDS YISHUN Pulau SARIMBUN SELETAR RESERVOIR EXPRESSWAY Punggol KRANJI NS7 Barat KRANJI Pulau BUKIT TIMAH JALAN Punggol NS14 KHATIB KAYU Timor KRANJI Pulau Pulau LIM CHU KANG RESERVOIR SELETAR PUNGGOL Serangoon Tekong KRANJI SINGAPORE RESERVOIR PUNGGOL (Coney Island) WAR ZOO AIRPORT Pulau Ubin MEMORIAL NEE LOWER SELETAR NE17 SOON RESERVOIR PUNGGOL Punggol EXPRESSWAY UPPER NIGHT TAMPINES EXPRESSWAY (TPE) LRT (PG) NS5 SAFARI SELETAR YEW TEE RESERVOIR MEMORABLE EVENTS AT THE WATERFRONT (SLE) SERANGOON NE16 RESERVOIR Bukit Panjang SENGKANG RIVER Sengkang LRT (BP) SAFARI With 33 versatile meeting rooms covering an impressive 850 square metres, SENGKANG LRT (SK) CAFHI JETTY NS4 CHOA CHU YIO CHU CHOA CHU KANG KANG CHANGI the Waterfront Conference Centre truly offers an unparalleled choice of meeting KANG NE15 PASIR NS15 BUANGKOK VILLAGE EASTERN DT1 BUKIT YIO CHU KANG TAMPINES EXPRESSWAY (TPE) BUKIT PANJANG (BKE) RIS Boasting a multi-sensory dining experience, interactive Grissini is a contemporary Italian grill restaurant spaces with natural daylight within one of the best designed conference venues PANJANG HOUGANG (KPE) EW1 CHANGI PASIR RIS VILLAGE buffet restaurant, Food Capital showcases the best specialising in premium meats and seafood prepared in DT2 LOWER NS16 NE14 in the region. -

WARTIME Trails

history ntosa : Se : dit e R C JourneyWARTIME into Singapore’s military historyTRAI at these lS historic sites and trails. Fort Siloso ingapore’s rich military history and significance in World War II really comes alive when you make the effort to see the sights for yourself. There are four major sites for military buffs to visit. If you Sprefer to stay around the city centre, go for the Civic District or Pasir Panjang trails, but if you have time to venture out further, you can pay tribute to the victims of war at Changi and Kranji. The Japanese invasion of February 1942 February 8 February 9 February 10 February 13-14 February 15 Japanese troops land and Kranji Beach Battle for Bukit Battle of Pasir British surrender Singapore M O attack Sarimbun Beach Battle Timah PanjangID Ridge to the JapaneseP D H L R I E O R R R O C O A H A D O D T R E R E O R O T A RC S D CIVIC DISTRICT HAR D R IA O OA R D O X T D L C A E CC1 NE6 NS24 4 I O Singapore’s civic district, which Y V R Civic District R 3 DHOBY GHAUT E I G S E ID was once the site of the former FORT CA R N B NI N CC2 H 5 G T D Y E LI R A A U N BRAS BASAH K O O W British colony’s commercial and N N R H E G H I V C H A A L E L U B O administrative activities in the C A I E B N C RA N S E B 19th and 20th century, is where A R I M SA V E H E L R RO C VA A you’ll find plenty of important L T D L E EY E R R O T CC3 A S EW13 NS25 2 D L ESPLANADE buildings and places of interest. -

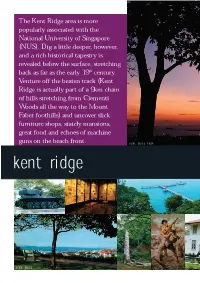

Kent Ridge Area Is More Popularly Associated with the National University of Singapore (NUS)

The Kent Ridge area is more popularly associated with the National University of Singapore (NUS). Dig a little deeper, however, and a rich historical tapestry is revealed below the surface, stretching back as far as the early 19 th century. Venture off the beaten track (Kent Ridge is actually part of a 9km chain of hills stretching from Clementi Woods all the way to the Mount Faber foothills) and uncover slick furniture shops, stately mansions, great food and echoes of machine guns on the beach front. KENT RIDGE PARK kent ridge KENT RIDGE west 2 3 Your first stop should be Kent Further south are the psychedelic Ridge Park (enter from South statues of Haw Par Villa (Pasir Buona Vista Road). Climb or jog Panjang Road). And moving to the top of the bluff for a eastwards is the superb museum, panoramic sweep of the ships Reflections at Bukit Chandu parked in the harbour far below. (31K Pepys Road), a two-storey The area is a regular haunt for bungalow that commemorates, fitness freaks out for their daily via stunning holographic and jog from the adjoining university. interactive shows, the Battle of If you have time, join the Bukit Chandu that was bravely fascinating eco-tours conducted led by a Malay regiment. by the Raffles Museum of Another popular destination in Biodiversity and Research the area is Labrador Park (enter REFLECTIONS AT BUKIT CHANDU (Block S6, Level 3, NUS). from Alexandra Road). Dating back to the 19 th century, the park was the site of a battlement guarding the island against invasion from the sea. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France.